Floating Points: “Recording at 96kHz is definitely not cool… it’s completely pointless!”

Sam Shepherd on why he hates MIDI, loves Buchla and can’t get on with Eurorack

Best of 2019: The electronic music scene can be a curious mix of innovators, chancers and copyists, with the occasional genuine maverick.

Sam Shepherd’s Floating Points most definitely falls into the mavericks camp. Never one to tread water, his 2015 debut album, Elaenia, took the promise of his earlier EPs (Vacuum and Shadows), both released on his own Eglo imprint, and blazed a trail further into the outer reaches of electronic sound, which helped cement Floating Points’ reputation both in the studio and on the live stage.

Sublime new album, Crush, really is another quantum leap forwards for Floating Points. From the jittery synths and strings of opening track Falaise, Shepherd takes us on an immersive sonic journey through the full capabilities of his musicianship and his armoury of desirable synths and drum machines.

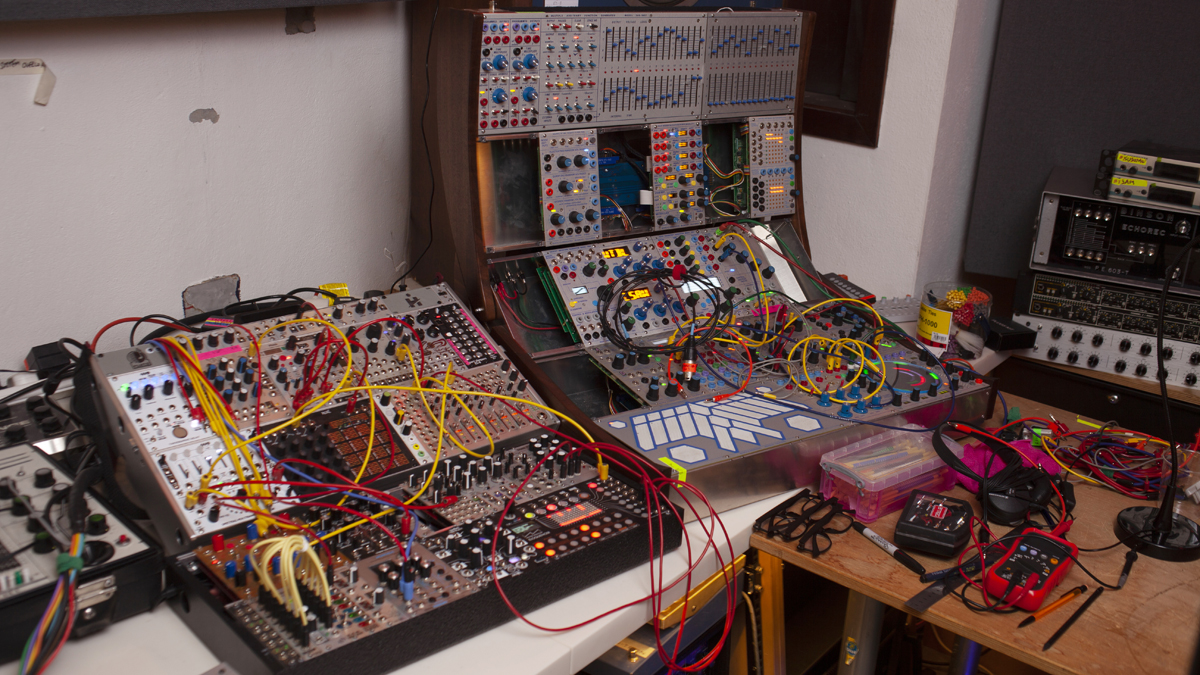

Crush is an intense but beautiful trip forged over five weeks in Shepherd’s subterranean Aladdin’s cave studio of flickering modulars and choice vintage gear.

We eagerly went to London’s easterly parts to visit Shepherd in his electronic bunker (where his studio experiments/solderings are ably assisted by studio manager, Tim) to find out more about Crush and to catch the wave of Shepherd’s enthusiasm for all things Buchla, and to learn of his desire to find a more expressive way of playing machines. Where to begin, really?

The record is maybe a little rough around the edges - because it’s basically a live show in a lot of places.

Reading the press release for Crush, it would appear we have Coachella to thank for the wonderful new direction of the album?

“That was the last gig of a big run of live shows with my band. The band was formed as a result of the Elaenia album, consisting of two guitars, bass, drums and me on the Rhodes, Solina and tons of Buchla stuff.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“Onstage we had quite a mad setup with everything running off a Dante network, which was quite unique, I think, for touring bands at that time.

“Our sound engineer is a guy called Michael Parker who works with Franz Ferdinand, Tame Impala, The XX and others. We wanted to use this system because I could cleave channels into a looping system onstage. We had a drum rack onstage and did a lot of drum processing there so we had racks of API pres that would create a little sub-mix using an API 3124MB, which then go through Distressors and various things. We left that fixed but the outputs would go onto the Dante network to go front of house and side of stage where we could do the monitors ourselves with our phones and some Behringer mixers.”

Gives you a lot of control of things from the stage, doesn’t it?

“I could also cleave things into my computer onstage; I can then loop the drums and send them back onto the Dante network, which lets me do things like having loops of the real drums with the Buchla and putting the drums through it and processing them with frequency shifters and other mad stuff. By the end of that tour the level of musicianship was so high that we were basically jamming the gigs, which was a lot of fun for us.”

So, did that just gradually evolve into the basis of Crush?

“My friends in The XX suggested I come on tour with them and just jam for half an hour before they went onstage, so I took a small Buchla rig and a Korg Volca Beats, which seems to get an unfair amount of grief, but I think it’s a sick little drum machine and it’s the central theme to one of my tracks, Kuiper. So, I made a beat on the Volca, put it through the Buchla delay then into another delay to create a different rhythm. Then I’d start playing these drones and build it up for half and hour until it was pretty cacophonous by the end.”

Jamming on the fly live with your Buchla setup must really help to make you more au fait with its intricacies?

“I learned a lot from that experience and getting fluent with the equipment. I brought that setup back to the studio and that became the new heart of the studio. Again, because everything in the studio is on Dante, we use this DAD AX32 as the digital heart of it. Then I could do stuff here quite easily and add it to the Dante network and record it on either side of the studio.

The Dante stuff, has been a game-changer here and being able to record anywhere. Recording at 96kHz is definitely not cool though… it’s completely pointless! It’s annoying as I can kind of hear that it does sound better but my poor computer just dies with it. I store everything on Dropbox, too, and there’s definitely got to be an environmental argument against using such high bit-rates.”

Taking a big modular rig live when it’s not a live instrument (per se) seems brave?

“I think Don Buchla wanted to make live performance instruments and the Music Easel is the perfect example of that, but I use the 200e series stuff, which is, I guess, a little bit more intended for studios. I’ve got keyboards that are touch-sensitive and can be very performative but you’re right: there are elements of this that can be super dry.

“The sequencer is so boring. You spend a lot of time programming it but you can’t perform with it live. I know that Suzanne Ciani uses the Buchla sequencer and runs it into the MAGF (Multiple Arbitrary Function Generator) 248. She turns it into a three-dimensional sequencer, which is so cool. So, there’s a sequencer running linearly, but there’s another sequencer running against that one. She’s such a genius.”

What initially made you go with the West Coast modular system rather than Eurorack?

“Because it looked cool! [laughs]. Bear in mind that I was 18 and just got to uni and had a little job. I saw a picture of a Buchla 200e and thought, ‘that looks sick’. I called them up and it was actually Don Buchla who picked up the phone and he told me to start off small with three modules… an oscillator, an envelope generator and a filter. He asked if I had a mixer, which I did, so I could get the audio out and monitor it.

“A few weeks later, this little modular synth arrived [laughs] even though I’d not agreed to buy it! A couple of weeks later I called and told him how brilliant it was and he said, ‘do you want it?’ so I paid for it then.

I called [Buchla] up and it was actually Don Buchla who picked up the phone and he told me to start off small with three modules… an oscillator, an envelope generator and a filter.

“Fast forward to 15 years later and I’ve amassed a full rack here, two touring racks and three other cases of different sizes. It’s a format I’ve grown to love… more so than Eurorack and I think that’s because I know it so much better. But also, it’s all largely made by one manufacturer, so there’s a consistency to the way it works.”

You do have various choice bits of Eurorack dotted around the place too, though?

“I’ve got some wicked Make Noise stuff and various other Eurorack modules but I don’t really know what it does as I don’t spend enough time with it. Maybe I’m giving Eurorack a hard time but it’s entirely my fault as I’m just a little frustrated with it. I’m just not getting on with it.”

You have some very desirable bits of outboard too. Has that been the same process of accumulation over the years?

“Yeah, although I don’t consider myself to be a knowledgeable studio engineer-type person. The first recording I ever did in a studio was at Abbey Road Studio 2. Up to that point I’d been doing everything in my bedroom. I just remember the drum sound was so sick. Sam Okell was the engineer and he put a Coles 4038 Mono over the drums into a Neve 1073 then through a Fairchild compressor, which I gather is a classic signal chain if you’ve the money. It sounds phenomenal!

“So, when it came to getting my own studio together and I wanted to start recording drums, I found my own pair of 4038s for £30 at one of those BBC auctions. I’ve lucked out with lots of the equipment here. I got these Retro 176s because I couldn’t afford a Fairchild. The people at Funky Junk have always been good to me and let me try out bits of gear.”

Does it lead you to prefer hardware over software?

“No because I’m evangelical about whatever I like the sound of. I love the ES1 synth that’s built into Logic. People have asked how I’ve got certain bass sounds and which crazy, modular system I use? It’s often the ES1. I’m all about the Volca Beats and MFB drum machines… whatever sounds good to me.

“There’s a lot of dirt on the album. I use an early Roland distortion pedal that sounds really unhinged. Preamps are a good example… Funky Junk once got me a (Thermionic Culture) Fat Bustard and a Prism soundcard running into some API 550A EQs and that was my studio for about six years. I made all my early records on that setup in a rack in my bedroom.”

How did your setup evolve from there?

“I got this API desk because I’d used one on a session at Fish Factory Studios once and I just found it so easy to use. It wasn’t about it having a particular sound or whatever, I just found it easier to use than the Neve. I bought the desk fully loaded but I’ve gradually got rid of all the EQs because I think I get more control from different EQs like the outboard Neves or from ones in the computer.”

What’s the spine of this studio now?

“We use a hybrid digital/tape setup now. So, there’s a 24-track Otari, which I’ve lent to a friend at the moment. EQing that stuff is a bit tricky so we usually run in with the EQ. I’ve got some Pultecs now, which are brilliant. I’m really about seeking good sound and I don’t care if it’s analogue or digital.

“I think tape is great because it’s quite forgiving of bad recording but, now especially, there’s nothing between that and digital. Soundcards nowadays are brilliant because the difference between a good, end-of-the-spectrum RME and one of these DAD things is about £10k but there’s absolutely no discernible sonic difference between them at all.”

Since we’re sitting right beside it, it would be remiss of us not to ask if your beautiful ARP 2600 features much on the new album?

“Absolutely. The entire track LesAlpx is basically a big drop from the 2600. The DJ Patrick Forge gave me his ARP Odyssey to look after when he moved to Japan, as well as a Wurlitzer. That Odyssey has been on pretty much every single record I’ve released… I know it inside out. As an expressive instrument it’s just brilliant.

“My friend Rick Smith in Vancouver is a synth guru and he’s got all kinds of esoteric old machines. He’s been my synth oracle and whenever I’m over there I’ll go hang out and mess about with his synths. He’s got one of the two Buchla 700 series ever made. He had this never-opened ARP 2600, which I bought. It was mad opening it up knowing it’d never been switched on!”

They’re certainly held in very high regard in the modular fraternity, aren’t they?

“Absolutely, but most people are into the grey-faced 2600; I really like these later, orange and black-faced ones. The filter is a little thinner, my understanding being that it was initially a Moog filter they used, but Moog asked them not to use them. So, this version has a slightly thinner filter, but you can have it at -50dB in the mix and you’ll still hear it cutting through. I do like machines that can be a musical extension of yourself.”

What others fall into that category in your studio?

“I feel that same thing about the Yamaha CS Reface. It’s an incredible synth for the money. It’s got thunderously low, good bass on it. When I was doing The XX tour, I took the Reface with me and the pads are nice, the filters are nice and it’s so rich-sounding. It’s 2019, though, so more people should be building synths like this… there are too many average-sounding synths on the market now.”

Any other new trinkets that are firing your imagination?

“I’m using the Roland TR-8S at the moment, which sounds brilliant and you can load your own samples into. A lot of the new live show revolves around that, so the more I use it, the more familiar I get with it. You can do all the last-step stuff with it, which is fun for me, making polyrhythms.

“I also got the Buchla 252, which is their newer sequencer that looks like a circle of steps. It can run 16 steps on the outer-ring then 15, 14, 13 etc. You can run three sequences at a time. So, I could run a 16-step classic sequence against 11 against 5 to create really complex polyrhythms. They can either run independently of each other or locked to the one bar. It’s really fun to experiment with in the studio but live…[laughs] a little dry!”

Is the Therevox nestled in the other part of your studio part of the quest for more expressive interaction with your synths?

“That one is a gamechanger for me. I’ve had it for about five years but haven’t really recorded too much with it. It’s on the new album quite a bit; the beginning of Environments for one. That whole thing of it being expressive… I just rest my hand on the two little paddles that control the oscillators and volume. The ring lets you wiggle your finger and create the vibrato.

There are too many average-sounding synths on the market now.

“I feel like that’s where the instrument becomes an extension of my body and that’s so important with electronics. These things are so dry; they’re just capacitors and resistors and boring current moving around. I think it’s important with electronic music to be able to see through the instrument to the person playing it.”

Were all the tracks on Crush forged through jamming with the modular stuff?

“A lot of it was but there are various ways that I work. I have a couple of systems here that allow me to record stuff… the Dante thing is so powerful and we’ve got racks of ADs that are patched into various points on the modular, listening to direct output from the live-rig setup.

“So, I could hit ‘record’ for the whole setup and it would be recording every single drum machine onto separate channels, every single effects return on separate channels… everything. That means that I can go back and fix things but then I’m pretty lazy. So what I usually end up doing is putting a Sound Devices recorder there just under the computer screen and that just records everything that’s going on in the studio in stereo. We’ll usually just chop up that stereo file and use it. That’s why the record is maybe a little rough around the edges - because it’s basically a live show in a lot of places.”

Will this be your MO for the next project?

“There’s more to be done with it but I’m also looking forward to playing the piano again and also getting back with the band at some point. I’ve definitely enjoyed the process of this album as I had a few drum machines I hadn’t used for a while like this MAM one, which is all over the album. I’d sit and program some beats, usually fairly basic ones, then program a basic one for the Buchla; I use MIDI a lot for the Buchla. I hate MIDI but I use it… when is someone going to invent something that improves on MIDI?

I hate MIDI but I use it… when is someone going to invent something that improves on MIDI?

“I’d be interested in knowing if anyone else is having trouble with the clocking on the TR-8S, as it’s a real pain live. I’ve got a laptop live that clocks everything. It clocks the Buchla and it’s fine, even though I don’t think it handles MIDI all that well. Once you start giving it too much it starts crashing and skipping beats. The TR-8S just goes out of time all over the place and I don’t know whether it’s because of its clock or Ableton’s clock but I know the original TR-8 used to clock fine! Everyone should be working towards a new standard that keeps everything clocked.”

Does your EMS Synthi get much of a run out?

“I love the Synthi and the filter on it is so nice and I understand why it’s fetishised but it’s pretty difficult to play something that’s in tune. We actually use the Synthi in the live show too, for the visuals, as the oscillators can go so high that we use that to generate the figures which I then use my Buchla stuff to frequency modulate.”

What’s your live setup going to consist of for forthcoming shows?

“It’s me, two Buchlas, a Sonosax mixer, and some drum machines with delays that are based in the Buchlas. Some reverbs, a looper and the little Yamaha Reface CS. Some of the stuff will sound closer to the album versions than others.”

Any other software/hardware you particularly like at the moment?

“We got iZotope Ozone recently and that’s been really good for mastering. We’ve got a lathe here, although I don’t trust myself to cut the lacquers for my own album. I do dub-plates for DJing, though, which is useful.

“I like this Waves MaxxBCL as it’s a blunt tool. I remember when I got my first record mastered at Transition the guy, Jason, was doing all the dubstep records. That dubstep sound was mainly from his studio as he’d add ten octaves of Sub to every cut. He had one of these and I had to get one.”

Future Music is the number one magazine for today's producers. Packed with technique and technology we'll help you make great new music. All-access artist interviews, in-depth gear reviews, essential production tutorials and much more. Every marvellous monthly edition features reliable reviews of the latest and greatest hardware and software technology and techniques, unparalleled advice, in-depth interviews, sensational free samples and so much more to improve the experience and outcome of your music-making.