“He was a maniac… he said ‘Turn every knob 180 degrees from where it is now and see what happens’”: How Lindsey Buckingham took Fleetwood Mac on a creative left-turn on Tusk after Rumours

“A noisy, bouncing fuzz-monster that makes no kind of sense in the universe of mainstream 70s radio pop” – but is Fleetwood Mac's flop a misunderstood masterpiece?

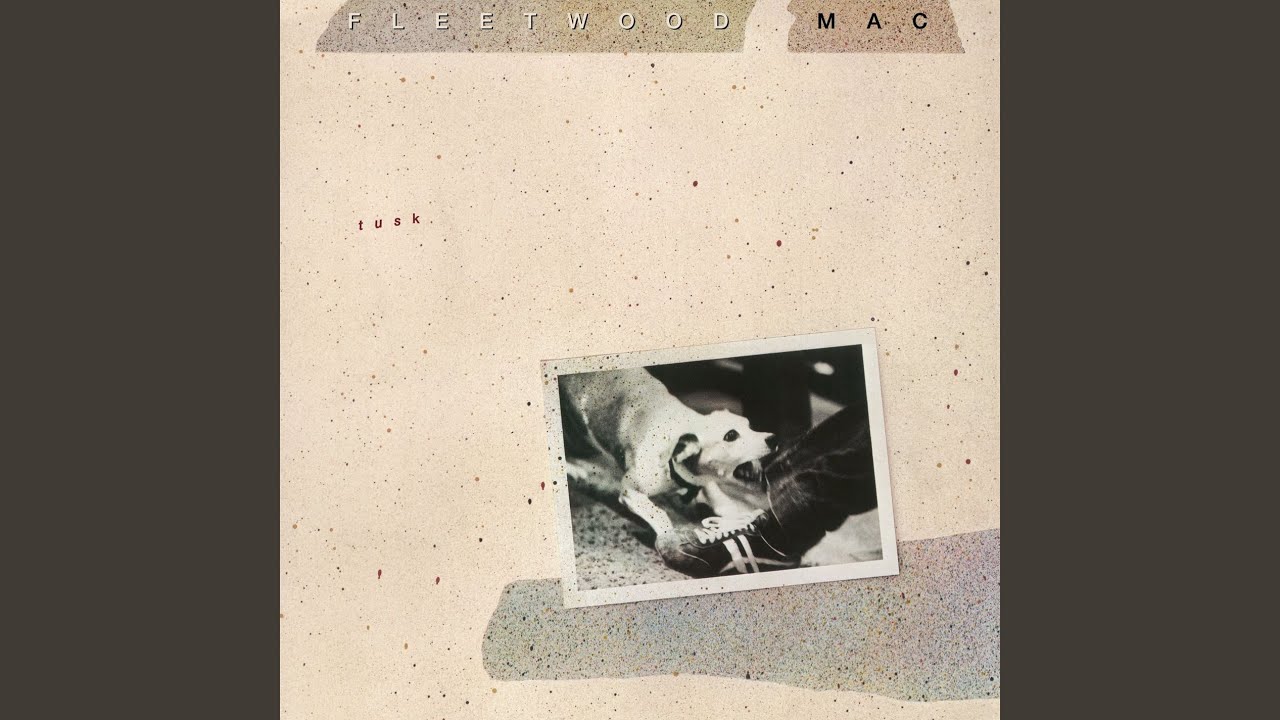

The one colossal downside of creating a masterpiece, as any artist who has done it knows, is that following it up with something as sublime, or even better, is a Herculean task. One option is to not even try to compete with your past work, but break new ground and venture in a completely different direction. This is precisely what Lindsay Buckingham did with Fleetwood Mac’s 12th album, Tusk.

Created in the wake of their colossally successful album Rumours, Buckingham took the reins of the fractured, burnt-out band and created a sprawling, yet utterly brilliant 20-track double album. Commercially it was a flop and regarded at the time as a grand folly. It cost over one million dollars and was the most expensive album ever made at that point. But over the decades that followed, Tusk has slowly become regarded as a classic, a peerless album driven by a powerful creative vision.

At some point, Lindsey was starting to get very experimental in his own studio and was veering a little left of centre

Christine McVie

The tour to promote Rumours reportedly reached new levels of hedonism. But when the dust settled, they were forced to address the daunting subject of a follow-up album and it was Lindsey Buckingham who stepped forward to take control.

“At some point, Lindsey was starting to get very experimental in his own studio and was veering a little left of centre,” the late Christine McVie told Dylan Jones for GQ magazine in August 2020. “He had already decided that he wanted to make a solo record. In order to keep him within the fold we all said, ‘Well, look, let him do his experimenting and incorporate it in the album somehow’. That’s how in essence it came to be a double album. There was all this experimentation flying around, especially from Lindsey’s point of view.”

Tusk would become Buckingham’s tour de force. He contributed nine of the album’s 20 tracks, overseeing production and crafting a hugely ambitious album that has been compared to Smile, the masterwork created by his hero, Brian Wilson.

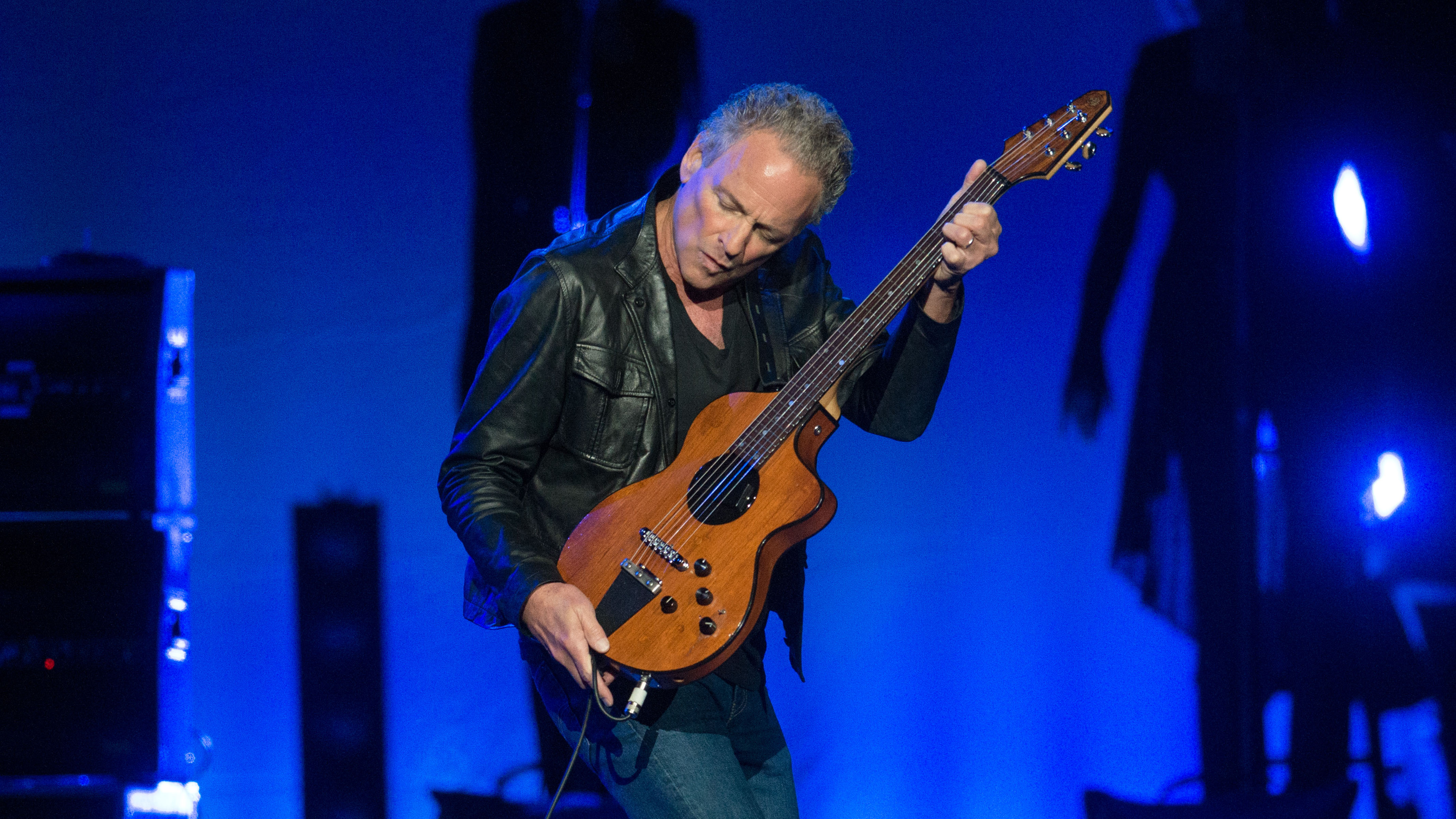

Recording of Tusk took place between 1978 and 1979 at the band’s new custom-built studio at Village Recorders in west Los Angeles. From the outset, Lindsay Buckingham was determined to make Fleetwood Mac relevant in the post-punk world. He was infatuated with bands such as Talking Heads and keen to challenge preconceptions when it came to what was achievable in the studio.

Early on, he came in and he'd freaked out in the shower and cut off all his hair with nail scissors

“He was a maniac,” recalled co-producer Ken Caillat in a feature by Jeff Giles on the making of Tusk, published in Classic Rock in 2015. Caillat had already worked with the band on Rumours and clearly noted a change in Buckingham: “The first day, I set the studio up as usual. Then he said, ‘Turn every knob 180 degrees from where it is now and see what happens’. He'd tape microphones to the studio floor and get into a sort of push-up position to sing. Early on, he came in and he'd freaked out in the shower and cut off all his hair with nail scissors. He was stressed.”

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Anyone dropping the needle on to the opening track of Tusk for the first time could be forgiven for thinking that it was business as usual – Rumours Part Two in everything but name – judging by Christine McVie’s glorious opening track Over & Over. It’s one of the album’s highlights, a moving and stately country rock ballad.

In Jim Irvin’s liner notes for Tusk: Deluxe Edition, Lindsey Buckingham recalls that the band decided to leave the song “in a fairly raw state, not too glossy in the production”. It’s a beautiful performance, understated and sparse.

Buckingham’s tasteful slide playing perfectly complements McVie’s warm, pure crystalline vocal tone. Dennis Wilson, who was dating McVie at the time, was present in the studio that day and was singing vocal ideas to McVie through the talkback microphone. It was allegedly his idea to use the descending chord progression from the chorus and build it into the section after the final verse.

There’s an expectation that the album’s second track will follow on in a similarly soulful, laidback vein. Wrong. Such assumptions are thrown to the wind as Buckingham’s The Ledge comes piling in, a manic, abrasive slice of punk-fuelled lo-fi.

On 24 June, 1978, the band recorded the song, with Buckingham plugging a Strat into a Fender Twin and Christine McVie swapping her Yamaha keyboard for a Hammond B3 organ. According to Ken Caillat and Hernan Rojas’ 2019 book Get Tusked: The Inside Story of Fleetwood Mac's Most Anticipated Album, Mick Fleetwood’s snare drum was tuned so high that “it sounded as though he was hitting a trash can lid”.

Fleetwood Mac did seven takes of the song before Buckingham called the session to a halt. The version that appeared on the album was mainly recorded at Buckingham’s home studio and featured a guitar and bass tuned down an octave, as the guitarist wanted it to resemble the higher notes of a bass guitar.

Clocking in at just two minutes and eight seconds, The Ledge confronts and challenges. The New York Times described the track as "a noisy, bouncing fuzz-monster that makes no kind of sense in the universe of mainstream ’70s radio pop” adding that “it sounds as if it were recorded live on a whaling ship in heavy seas”.

Buckingham’s fascination with new wave yielded some other strikingly left-field songs, such as That’s Enough For Me and Not That Funny. But where his vision really comes to fruition is on the title track, which was the first single from the album. Here, all of his experimentation and offbeat instincts bear fruit and elevate the song into something unique.

“Why don’t you tell me what’s going on? Why don’t you tell me who’s on the phone?” chant Buckingham and Nicks over the strident percussion.

Mick Fleetwood’s idea of getting the University of Southern California (USC) marching band to play along is inspired. A mobile studio was installed in Los Angeles Dodger Stadium to record the marching band and Ken Caillat used shotgun microphones to record the band as they moved. Stevie Nicks’ signature vocals are wrapped up in a defiantly new sonic template.

Another Buckingham high point is Save Me A Place, a sparse and simple 4/4 track with an ascending chord progression. Here, Buckingham’s floaty, underplayed vocal performance yields real emotive power.

Buckingham’s edgier contributions are offset by the pristine, shimming pop of Stevie Nicks and the emotive balladry of Christine McVie.

Nicks’s Sara and Beautiful Child are among her very best songs. In his 1998 biography To The Limit: The Untold Story Of The Eagles, author Marc Elliot cites a quote from Don Henley, who allegedly claimed that Sara was written about their unborn child. In a 2014 interview with Billboard, Nicks said: “Had I married Don and had that baby, and had she been a girl, I would have named her Sara... It's accurate, but not the entirety of it."

The song started out as a 16-minute demo. The band originally wanted Christine McVie to redo Nicks’ piano part and for Nicks to redo her vocals. But as Jim Irvin writes in his liner notes for Tusk: Deluxe Edition, the band realised that “the timing of Nicks’ vocal and piano on the demo was so individual that there was no way Chris could get in there”.

Fleetwood decided to play brushes on the recording instead of sticks to allow for a more fluid drum performance. In Jim Irvin’s liner notes for Tusk: Deluxe Edition, Fleetwood says he spent around 24 hours "dropping in phrases, schmoozing my way around her timing... that's the track that survived, with Stevie playing the piano.”

Sara is one of the absolute jewels on Tusk, and one of Nicks’s finest compositions. Tyler Golsen of Far Out noted that the song “acts as one long crescendo, never once rushing its way to the explosive finale,” and is “one of the many anchors that keep Tusk from flying off into some other dimension”.

Another Nicks’ composition that elevates this album is Beautiful Child. In a 1979 interview with Circus Weekly magazine, Nicks described it as her "most special song". In a Q&A interview in 2013 Nicks said that Beautiful Child was written about her affair with Derek Taylor, the former publicist for The Beatles.

No one in the band really made a judgement about it until it became apparent that it wasn’t going to sell 16 million copies

Lindsey Buckingham

Tusk was released on 12 October 1979 and as Dylan Jones noted in his GQ piece on the album in August 2020, “the public’s expectations, as well as those of the record-label executives, were almost vertical, and by the time the band’s magnum opus was ready, the consensus seemed to be that Tusk was going to single-handedly rescue the record business.”

It wasn’t to be. The album was a commercial disaster in comparison to its predecessor. It did yield two Top Ten singles in the US, Tusk and Sara, but by April 1980, it had sold 'only' four million copies. It also cost over one million dollars to make and was the most expensive rock album ever made at that point.

“Oddly enough,” reflected Lyndsey Buckingham in GQ, “no one in the band really made a judgement about it until it became apparent that it wasn’t going to sell 16 million copies. It was a double album and certainly confounded everyone’s expectations – which is what it was meant to do.

"Once it became apparent that it wasn’t going to be a massive commercial success, then the band members... Mick would say to me, ‘Well, we went too far. You blew it’. And it was very hurtful. We were out on the road and I’m going, ‘Oh my God, how am I gonna react to this?’”

Lindsey Buckingham: 5 Fleetwood Mac and solo songs you need to hear featuring the guitar maverick

In the decades that have followed, with commercial pressures in the distance, Tusk’s merits have been completely reassessed. A 2020 retrospective in Classic Rock praised Buckingham’s “brilliant left-field songs”.

On the release of Tusk: The Deluxe Edition in 2016, Amanda Petrusich in Pitchfork concluded that Tusk is a beautiful and terrifically strange album”. Kris Needs in Record Collector was equally enthralled.“Tusk can now be appreciated as a stormy but monumental chapter in Fleetwood Mac’s action-packed 48-year history,” wrote Needs, “a classic statement of excess to bring down the curtain on the '70s with a roar rather than a whisper.”

Neil Crossley is a freelance writer and editor whose work has appeared in publications such as The Guardian, The Times, The Independent and the FT. Neil is also a singer-songwriter, fronts the band Furlined and was a member of International Blue, a ‘pop croon collaboration’ produced by Tony Visconti.