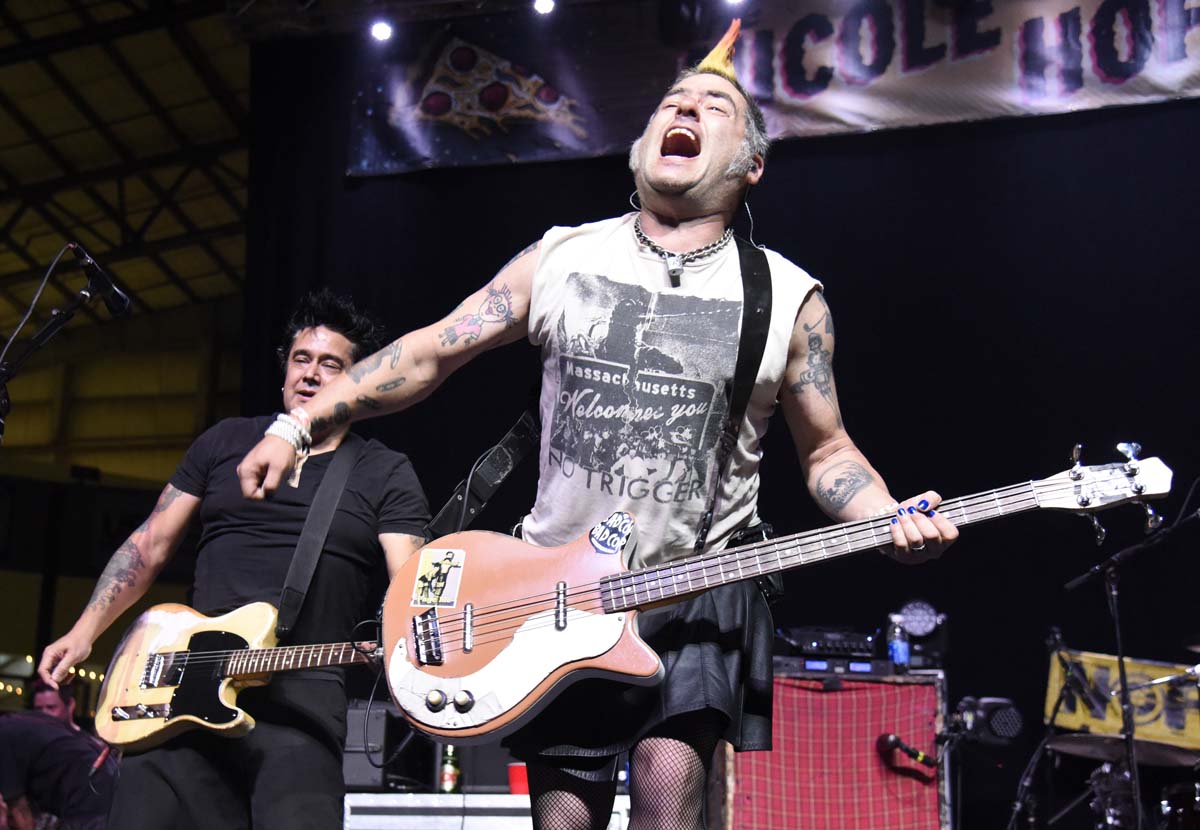

Fat Mike interview: “I’ll throw in a cool bassline every now and again but I want to be known for songwriting, and how authentic we are“

The NOFX frontman on the Beatles, perfectionism and why choruses suck and should be avoided

Fat Mike is damn good conversation. He talks a little like he writes music. You don’t know where he is going to go with it but there is sure to be a few surprises en route, a few verbal hand grenades.

This particular conversation opens with his memories of spending New Year’s with Oasis – “Oasis played Oasis songs for, like, four hours; they really do believe they are that good.”

It then takes a hand-brake turn into the delicate logistics of sexualised cocaine consumption, and his impulse to share such vignettes in verse (as on Fuck Euphemism).

After which, it proceeds right on through to the business of offending the easily offended before terminating at his joy at landing a C#min chord just as he sings the lyrics “We set sail into the dark and sharpest sea.“ A detail, he assures us, no one will notice but it delights him nonetheless.

Taking place just as Fat Mike [Mike Burkett to the authorities] is settling into a newfound sense of equilibrium, it is also a conversation that reflects that distinctly NOFX temperament that sees the Californian punk stalwarts ping-pong between unfiltered humour and the super serious. Lately, Fat Mike has been doing a lot of thinking.

“You know, I went to rehab a few months ago,” he says. “I learned a lot. It was fun. Being sober, and going through Covid, I have 40 new songs. Over the past few months, every day I spend writing. I just love writing right now, and being clear-headed with nothing else to do? It’s pretty cool. We are already working on a new record.”

Being sober, and going through Covid, I have 40 new songs... Every day I spend writing. I just love writing right now, and being clear-headed with nothing else to do? It’s pretty cool

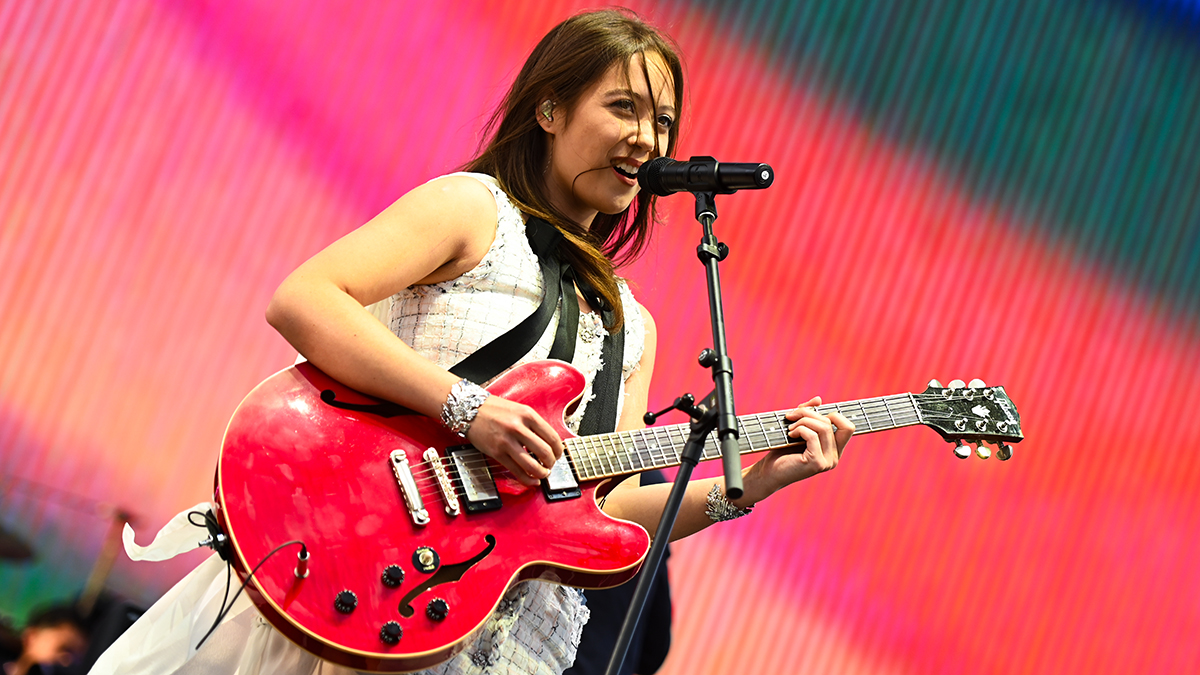

As for surprises, who here took the NOFX bassist/vocalist and punk rock impresario as a perfectionist? Not us. Maybe it is the chaos of the live show – the chaotic whirl of controversies past, present and future and the shock blue hair that can give you the impression that NOFX are a throw-and-go outfit, happy to let the chips fall where they may.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

But that’s all after the fact. In the studio, Fat Mike obsesses sweats the small stuff 24/7. NOFX’s punk sound is kinetic and iconoclastic, gallows humour abutting wry polemics, yet it is built of tiny details and fine margins.

“Absolutely, I spend so many painstaking hours,” he says. “I mean, I am in the studio for every single fucking note that’s played. I will not let anything go, any drum part, any roll, I make sure it is perfect. It drives me crazy.”

This sensibility is why Single Album is now just that – a single album, as opposed to the perfect double album that the Californian punk stalwarts had lined up. Songs were ready, but they had to go. “It’s not competitiveness,” explains Fat Mike. “It’s just I want NOFX to stay a relevant band, lyrically and musically.”

He pauses a second at the thought of a it: “Pink Floyd were the only band who made a perfect double album.“

I am in the studio for every single fucking note that’s played. I will not let anything go, any drum part, any roll, I make sure it is perfect. It drives me crazy

Single Album was always going to be called just that – at least none of the T-shirts had to be reprinted. The songs that were cast aside will be revisited at some point. Those that made the cut find NOFX turning their acerbic observations inwards once more, like when they play around with their most famous song, Linoleum, reworking it as Linewleum with Avenged Sevenfold guesting.

However painstakingly it was conceived, Single Album offers another freewheeling trip through Fat Mike’s antic wit and invites you to confront the bleakness head on with tracks such as I Love You More Than I Hate Me and Birmingham, and the perpetual motion of The Big Drag – a song that walks NOFX’s sound off the cliff. Maybe there is the best place to pick up the conversation…

It is nice to hear you so enthusiastic about writing, that sobriety is treating you well, because The Big Drag, that kind of sounds like a swan song…

“It is ominous, and it is a coda song. It should be the last song on an album, but I put it first because it sets the tone. That is one of my favourite songs I have ever written because it is different, and, actually, every measure of the song is a different length, and the drums don’t make sense.

“The bass never lands on the note – it’s always roaming. Listening to that song, it makes you just feel insecure about yourself. It keeps you in an awkward position. But it does ground at certain points.”

When did you write these songs?

“This record was written and recorded a year-and-a-half ago. Way before Covid. I was in a depression. I had never been depressed before. But I was very lonely and depressed, going through a divorce. I was drinking a lot, doing a lot of drugs, and all these songs were written during that process, usually at three or four in the morning.”

I was very lonely and depressed, going through a divorce. I was drinking a lot, doing a lot of drugs, and all these songs were written during that process, usually at three or four in the morning

How difficult is The Big Drag to play?

“Oh, yeah… [Laughs] I used to say we would never play [The] Decline, and then we ended up playing it. But we will never play The Big Drag. No, it’s much too difficult. I was trying to air-drum to it, y’know – and I have heard it a hundred times – and I couldn’t do it!

“Everything about it is weird, and having no measure the same time, you have to concentrate so hard. We couldn’t record it all at once! You can’t do it. We’d lay down the guitars, then the vocals, and then we did drums at the end. We had to go as we went.”

So that was a little more studio magic, gaming it out and planning every part?

“Yeah, we did a demo of it, which was not a lot different but different, and we just wanted the drums to feel perfect and you couldn’t get it in one take.”

Again, it had to be perfect… It is a change of pace, keeps the audience guessing.

“When we play shows, people don’t ask for the old songs anymore. They want to hear new albums. We are not a nostalgia act, but that takes a lot of work. Our new album opens up with a six-minute song that I don’t think sounds like any other song that I have heard.”

The closer we look at your compositions, the more complex they are. Yet, when we just listen to them, they are fun. Enjoying them is easy.

“I write complicated chord progressions because I let the melody dictate where it is going to go. ‘Oh, I think I’ll try this chord. Does that one work? No. Does this? No…’ And that is how I end up with eight/sixteen chord patterns.

“It is very much like the Beatles. Not that I have studied the Beatles – I think I know how to play three songs – but the Beatles played that song All My Loving, and that sounds like a simple pop song, but it is a sixteen-measure pattern.

We are not a nostalgia act, but that takes a lot of work. Our new album opens up with a six-minute song that I don’t think sounds like any other song that I have heard

“You don’t think that when you hear it. It’s just catchy. So, that’s the paradigm I use, especially the new songs I have been writing. They are getting so weird. I mean, I think they are really catchy but I can’t keep track. I write it, and I have to record it all, and then have to go back and figure it out. I won’t write a melody to a chord progression – they get written at the same time.”

It is like you are following a train of thought, chasing the melody to its logical conclusion, and then that’s how you end up with so many different changes…

“Right! Changing chords, putting in a surprising chord is what makes your ear really happy. That’s why the Beatles have stood the test of time, and the Rolling Stones, while their songs might make you feel good, they are not interesting chord progressions. In fact, I made a greatest hits CD mixtape of the Rolling Stones, and there is only five songs on it. But, y’know, that’s me.”

There is something subversive about having ear-worm melodies and major keys in punk songs about serious subjects, maybe more so than straight-up monochrome anger.

“Yeah, and some people say, ‘What about your song Bob? That’s only two chords.’ We have one song that does that!”

And you have a lot of songs. Going back to melodies, that was an aesthetic choice. You could have gone more aggressive. Do you remember when you made that decision?

“I actually know the exact time. ‘Cos NOFX from ’83 to ’88 were just California hardcore. That’s what we listened to. Those were the bands that we knew. Then Bad Religion put out Suffer. We had just played a show with Fugazi at a squat in Amsterdam.

When I saw Op Ivy and they could not get through a song, or Social D in ’82, when they were so drunk they couldn’t stand up, those are the shows you remember

“I was thinking about quitting the band, because the tour was really hard and not successful, a lot of people didn’t like us, and then I heard Suffer. I listened to it four times in a row and it just changed my life. ‘All right, punk rock is great!’

“I wasn’t thinking of playing punk rock like the Dickies, Bad Religion and Social Distortion, but melody? We were going to be a melodic hardcore band. I couldn’t sing just yet. It took a few albums of off-key vocals, but that was the moment.”

Punk rock is a forgiving medium. As long as you land the vocal on the right note you’re fine.

“In punk rock, yeah… Or Radiohead. That guy can’t sing for shit. But playing live that is where I am not a perfectionist. I really don’t give a shite because it is about how much fun we can have. When I have fun, the crowd has fun.”

It’s hard to have fun if you are trying to be perfect.

“I used to see the Descendants and All. All would play perfectly for an hour-and-a-half, hardly any breaks, every note was perfect. And it was boring. I don’t want to see that. I could listen to the album.

“When I saw Op Ivy and they could not get through a song, or Social D in ’82, when they were so drunk they couldn’t stand up, those are the shows you remember. Those are the experiences, and those are the experiences that only punk rock can provide because you can’t get away with that in other styles of music.”

Is it harder being a punk these days? On one hand, you’ve got a culture that doesn’t like to be offended. Furthermore, it’s a difficult time for grassroots venues.

“Well that is kind of hard for me to say because I like doing outdoor festivals – because I have one! But also, I have a hard time playing clubs because I inevitably get hit with a fucking glass of beer or something, and I have a little PTSD from being onstage.

Steve Soto would make you want to be a better person. He was an original punk rocker and, really, the nicest guy in punk rock. And he was an influence on me as a bass player. His riffs on that first Adolescents album were great

“Because I say some things that offend some people and cross-dress – whatever the reason is – I am a target. When I am playing, I cannot look at the bass. I have to be looking at the crowd to see what is coming at me. And it doesn’t happen a lot, but you never know, and when you get hit in the face with a bottle it sucks.”

It is harder to have fun when there’s a missile coming towards you.

“Picture walking down the street every day to your work, and three times in a year you get hit in the face with something! [Laughs] It is PTSD. Yeah, that’s kind of weird about punk rock.”

You have a tribute to Steve Soto on the record. I wonder if you could speak a little about his influence, and how important he was to you, and to punk.

“Well, Steve Soto is an influence of being such a good guy. He would make you want to be a better person. He was a person who, if you we were in San Francisco, he’d call me and we’d go to dinner. He was such a cool guy, smart, funny, and yeah, he was playing with the Germs.

“He was in so many bands. He was an original punk rocker and, really, the nicest guy in punk rock. And he was an influence on me as a bass player. Some of his riffs on that first Adolescents album were great.”

You tell sad stories in comic settings and put it to punk rock. That is not a lot different to stand-up comedy.

“Yeah, well, I finally started doing stand-up comedy before Covid, and it is very difficult. But I don’t know if you have listened to Doug Stanhope before, but we are pretty good friends – I have done his podcast – and he does a bit in one of his routines where the punchline is, ‘I played chicken in my sleep. I play chicken in my sleep. I play chicken in my sleep. I play chicken in my sleep…

Classical music didn’t have a fucking chorus! Choruses are marketing

“And he says, ‘This is why I hate rock bands, because they can sing the stupidest line over and over and over again and people listen to it. In comedy, we can’t say the same line four times in a row. It sounds ridiculous. But some asshole rock star will sing Sally parked her Mustang out back four times. Words that mean nothing!’ When I heard that I thought, ‘Yes!‘ That’s why I don’t sing choruses. Because it is fucking lazy and boring.”

But repetition can be a powerful tool?

“No! It’s a powerful tool for the fucking label That’s what it is. You put a song on the radio and people hear it once but it sounds like you’ve heard it eight times, so it gets stuck in your head, and that’s marketing, dude. That’s not great songwriting. It is lazy songwriting.”

Linoleum! Our biggest song. Nothing rhymes. It’s just a little sad story about a little sad man

So you would always resist that urge to repeat a measure?

“Classical music didn’t have a fucking chorus! Choruses are marketing.”

Or jazz?

“Yeah, but jazz, they don’t give a shite. The jazz I like, Louis Armstrong, he will do a cool melody but then he will change it a bit, and all those songs were stories. They didn’t stick on a chorus; they told a cool story.”

And a cool story always has an element of surprise, and if you have a chorus, that element of surprise is gone.

“Absolutely! I just can’t do it. Linoleum. Linoleum! Our biggest song. Nothing rhymes. It’s just a little sad story about a little sad man.”

What more do you need?

“Yeah! And why is it our most popular? If it had a chorus and everything rhymed, I don’t think it would be. If there are three choruses you get sick of the song three times faster. That’s why Linoleum and Bob, some of our biggest songs, have no chorus, and the lyrics don’t rhyme either. It makes you want to hear it more.”

There’s something in that. Choruses are a little like your birthday – you look forward to them but they only disappoints you.

“Absolutely. And Linewleum? I love doing something that no one has done before, that no one has thought of before – not just writing a song about retiring your biggest song!

“It sounds exactly like Linoleum at one point but then the words, the chords and the melody changes at some point and it just fucks with your brain. Everyone who knows Linoleum hears Linewleum and goes, ‘What the fuck was that!?’ That makes me happy.”

Your fans want that. You’ve trained them, in a sense. You’ve trained their expectations.

“That’s an interesting way to put it. I always said, ‘I am not playing what my fans want. I tell them what they want to hear.’ They want truth. They want truth and they want surprise. They want their brain to go somewhere where it has never gone before.

“Why can’t music make people think differently about the world? It can! The way to do it is to be specific and not vague. Poetry is great, and sometimes I am poetic, but these days I am just right to the fucking point. Fuck euphemism.”

We’ve talked around different aspects of punk rock but authenticity is the designing principle, right?

“That is what it is all about. When you start to write for other people or write to sell units, then it all goes out the window.”

We should ask you about the bass guitar. What are you playing these days, the Danelectro?

“Yeah, live, I always use that bass. Even though the neck has been broken three times, it is still the same shit. I like playing it. It’s light. If you go to the Danelectro site, I am the only person on there, which is funny.

Bob Rock saw us play once and he was like, ‘What the fuck did you do to that bass?

“Bob Rock saw us play once and he was like, ‘What the fuck did you do to that bass? It sounds amazing.’ ‘Nothing!’ I bought for $300 used and I didn’t change anything. You can’t even intonate it; it’s just a wooden block at the back. I just play very softly.”

Softly?

“Very softly. In fact, I use a .60 pick, which bass players should use. A thick pick for bass players just makes you go sharp, and anyone who records bass players knows that. This is really cool, but I don’t know if you know what Jim Dunlop picks are, but I met him at this convention and I said, ‘You know I play this pick but you can’t silkscreen on it because it is a nylon .60.’

“And he’s like, ‘Yeah?’ I said, ‘Can you make me my own pick? Can you make me a mould?’ He was like, ‘Kid, we have had the same mould since the 1960s! We can’t change it.’ I said, ‘Why not? I think it would be cool.’ And he was wasted on tequila, and he said ‘Okay!’ And now I have my own Jim Dunlop picks that say ‘Fat Mike’ on them.”

What about amps?

“Whatever’s not broken. I think I used an Ampeg. I used to use Mesa/Boogie for most of my career but they stopped making the amp that I use.”

Because you play softly, do you turn it up loud like Steve Harris?

“No. I know what a bass player should do and most bass players don’t know what they are supposed to do. We are supposed to play light and have a round, even tone because it makes the guitars sound good. I play so light that I don’t go sharp when I record. But both our guitar players play light, because… Well that’s what they do.”

They are very underrated players. The tone is always on point.

“I don’t want to be known for what kind of shredding leads we can do. I’ll throw in a cool bassline every now and again but I want to be known for songwriting, and how authentic we are, onstage and in our music.”

How much music theory do you know?

“I never took theory. I learned it all from writing. My mind is pretty weird. I don’t remember lyrics. I don’t know anyone else’s lyrics – even my favourite bands. I can’t figure out songs. I have a very hard time figuring out other people’s songs. I just write on acoustic guitar to the Voice Memo on my phone and I arrange everything in my head. I’ll wake up in the morning and I arrange songs in my head.

“I learn as I go and I make mistakes. When I was writing Home Street Home, my musical, I wrote this one song, Missing Child, and it was a 40-minute write, and I went to this chord that I had never used before.

“When I should it to the orchestra they were like, ‘What the fuck is that!?’ I didn’t know. It was just a major C moved up a half-step, and it turns into some weird chord that works. The guy who was scoring the musical said, ‘I have never seen that chord.’”

That’s what you want. If no one has seen it, no one has played it.

“Yeah, and if I had taken music theory, I would never have come up with it.”

- NOFX's new album, Single Album, is out now via Fat Wreck Chords.

Jonathan Horsley has been writing about guitars and guitar culture since 2005, playing them since 1990, and regularly contributes to MusicRadar, Total Guitar and Guitar World. He uses Jazz III nylon picks, 10s during the week, 9s at the weekend, and shamefully still struggles with rhythm figure one of Van Halen’s Panama.