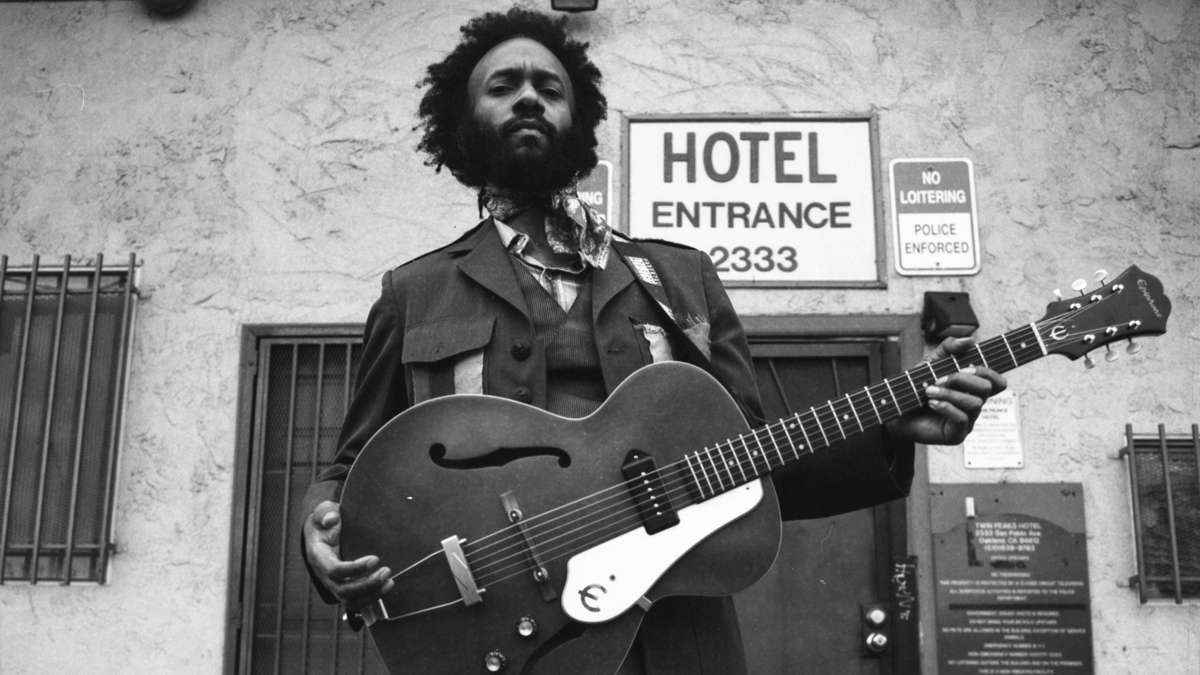

Fantastic Negrito: "I want the guitar tone that makes it feel like you’re in a club that you may get stabbed in"

Grammy-winning songwriter Xavier Amin Dphrepaulezz tells his incredible career, gear and recording story

It was the great American social reformer/abolitionist Frederick Douglass who once wrote, ‘If there is no struggle, there is no progress.’ Those words ring with a sense of truth for Xavier Amin Dphrepaulezz, better known today as the Grammy-winning Fantastic Negrito, whose backstory is one rooted in overcoming tough odds with valiant defiance.

As a young teenager, he sold drugs and carried weapons hustling the streets of Oakland, then after infiltrating music classes at California’s University Of Berkeley he started writing songs, which in turn landed him a record deal that got brought to an end following a near-fatal car collision.

Fast-forward 20 years, during which he’d been active in the afro-punk movement before settling down to become a medical marijuana farmer, and he’s recording under a new name...

Take us back to the beginning - you were heavily inspired by Prince and decided to sneak into music lessons...

I learned you could actually figure out a scale using each little key of the piano. That was the beginning of my musical education

“I did it because I came from poverty and there weren’t any opportunities to play any instruments. There definitely wasn’t money for lessons. I really admired Prince because I read he had taught himself and thought, ‘Wow, I could try that!’

“That’s the hustling lifestyle… you get it done. When people say you can’t, you prove them wrong. When people focus on what can’t be done, you focus on what can be done. I come from that tradition in the Bay Area.

“So I would dress up as nicely as I could and charm my way into the room, just acting as if I belonged there. I would listen to what they were doing, I didn’t really know at the time, but I eventually realised they were learning scales. It was a wonderment to me; I learned you could actually figure out a scale using each little key of the piano. That was the beginning of my musical education.”

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

It didn’t take long for you to land a record deal. Why was that?

“If I had any gift in this world that I felt I would always have, it was songs. So I just immediately started playing my own songs, it wasn’t like I learned covers. I was just trying to figure out what was going on in my head, which was quite a bit at that time. And that was it!

“I didn’t bother with cover bands; I just went straight into my own world of sequencers and drum machines. I never even played in a band before I got a record deal - I was just this guy banging around in a room with instruments writing songs. I feel like I got that deal because of my songwriting.”

How different were the afropunk years that followed?

“The first phase was being the young upstart. I had the desire to be a star, get a deal, get the best car, the best girl, the best house, the best clothing… I think that all ended when I was in a near-fatal car accident that damaged my playing hands and left me in a coma from three weeks.

Sunset Boulevard was so boring, people ended up spending lots of money but not getting anything back. So I opened my own illegal nightclub for musicians

“Then began the second phase when I was dropped from the label and on my own. That was very scary but also liberating. I went into the LA underground and started doing my own thing. That was when I first got involved in the afro-punk movement, which is pretty big now but back then it was really small, playing in basements and it was lots of fun.

“I had my own illegal after-hours clubs so we could do our own shows. Sunset Boulevard was so boring, people ended up spending lots of money but not getting anything back. So I opened my own illegal nightclub for musicians. It was a fun, underground and decadent - in a good way - lifestyle and I enjoyed it.”

But soon after you quit music and sold everything you owned…

“I didn’t think there’d be a next phase. After eight years of being very insecure, having to relearn everything with this hand, I’m barely able to hold the phone I’m talking on right now. That’s part of what drove me into the punk thing when I was just the frontman. It’s strange; I sold my equipment, every guitar, every keyboard, and my warehouse. I just didn’t want to play again. I was confused. I didn’t feel the honesty, I didn’t feel like I was connecting with music and didn’t know what to do about it.

“I sold everything but this one crappy guitar, which I couldn’t sell because it was so ugly and bad. A drug addict friend of mine stole something from me and gave that to me after feeling bad. So I kept that, went back home to the Bay Area, got married, had a kid and became… a cannabis farmer. Which was lucrative and great - I was very happy and learning so much about people while I was legally growing plants. It was so challenging and wonderful. I wasn’t selling it on the streets or anything; I was selling it to dispensaries.”

And yet, it was this new, calmer family life that pointed you back in the direction of music...

“One day, this baby that I had couldn’t go to sleep so I thought maybe I could pick the guitar up and strummed a G major. That one chord in that sunny room in Northern California on that afternoon shifted my life. There was this beautiful, undamaged being - no-one had told him that he sucked or didn’t fit in or made him feel invalid - and he just loved the sound of that chord.

“Right there and then I realised this was the true language of humanity. I felt like I’d been liberated, that I’d learned from this tiny being that it’s just a connection between our bodies and minds with the strings and wood. I wanted to feel like that again and went on the streets to connect with strangers. That was my rebirth and the third phase as Fantastic Negrito, the guy who walks around streets and bus stations playing songs for people.

“I like this third phase; it’s coming from a contributor who doesn’t want everything – the car, the woman, the fam. It’s just a love of music and a need to connect in a way that’s therapeutic for myself and my listeners.”

Though being mainly rooted in blues, there are elements of soul, hip-hop, rock, funk, African folk to your music...

My music is blues-based, but in my head Nevermind by Nirvana is a blues album. I’m like, ‘They got it… whatever it is!’

“I may have some East African Somalian blood on my dad’s side - I mentioned it once in an interview 20 years ago and it just stayed, so when I speak of Africa, it’s funny. I think of Africa, I think of R. L. Burnside or the voice of Skip James. Nothing is more African than that! It’s all a circle to me, so when I hear Hamza El Din, the Nubian player, it’s all the same and connected.

“For me, Africa came from the Delta players; there’s a connection between those minor scales on guitar and the continent. I’ve always listened to everything and have never really liked the idea of genres. I try to be as original as I can - listening to everything makes you influenced by everything, whether you like it or not.

“My music is blues-based, but in my head Nevermind by Nirvana is a blues album. I’m like, ‘They got it… whatever it is!’ That truth, that light which comes from a dark place. You can taste it, you can feel it, the music gets into your bloodstream. You can get stuck in overthinking this stuff.

“I believe Muddy Waters said it best when he said, ‘Blues is a feeling, man!’ When a human connects to that feel, nothing can buy that, you can’t put a price on that. It’s life. It’s blood.”

Having won a Grammy in your third musical guise, what have you learned from it all?

“There is only one you in the world. No matter what you are influenced by, there’s only one you. Black Sabbath showed us that! Tell your story, because it is extremely valuable. It can help people - you have to take your craft very seriously and enjoy it. Music is a beautiful thing; if you play something technical, enjoy it. If you have that, you’re gonna be okay.

“You can’t have all these great abilities without having a love for it; that’s when it all goes bad and I’ve seen it happen over and over again - I’ve been in this business for a long time. You have to live your music. There’s no secret scale to practice 20 times a day that works for everyone; it’s more about how you enjoy it and how you tell a story. For some people, practising 15 hours a day is how they enjoy it. For others, they might want to just go read something.

“When you enjoy it, that opens up the road to everything and it will sustain you for life. Our time is short and limited, so whatever you do, love it and walk towards that light.”

You’re also known for recording in art galleries rather than expensive studios...

I record in art galleries because I don’t like studios. Both my albums were made in a different kind of inspirational environment. I’m trying to record the feeling

“I record in art galleries because I don’t like studios. Both my albums were made in a different kind of inspirational environment. I’m trying to record the feeling. You can be in a perfect place, but how will you actually play when your hands touch those strings?

“Recording should be a magical experience. I’m pretty happy I haven’t recorded in a proper studio yet, though I’m sure that will piss off people who own studios. This way, I’m empowering other artists. They’ve taken all the money out of the music business, so you have to find more creative and innovative ways to do things. I didn’t play the clubs; I walked down the street.”

What was your main rig for recording your most recent album Please Don’t Be Dead?

“I use Epiphone a lot. There’s something about them; I think the guitars aren’t exactly beautiful and they’re just ugly enough. I want the tone that makes it feel like you’re in a club that you may get stabbed in, but knowing you probably won’t. As far as amps, there’s a guy in Northern California who makes my amps by hand called Cave Valley Amps, building Leslie speakers into them. I went back to those things over and over again - I love how they’re so unique and handcrafted.

“I was recording organ sounds, pianos, guitars, bass… I used seven different bass guitars on the album! I was using the James Jameson fretless setup, raised with the Styrofoam at the bottom. I used a wah-wah pedal on some parts. The acoustic parts were easy: stick a microphone there and boom, let it do what it does. I used a few fuzz pedals, too; I like the simple stuff with just one knob on it.”

It’s hard to imagine you getting into amp modelling or profiling, to be honest...

“Haha, man, that’s not me. I’m the guy that records all my vocals on a $200 mic. This kind of mentality saved me musically and as a producer/writer. It’s all about the shortest distance travelled when it comes to the sound. You don’t want it coming out conflicted. Sometimes I just plug in and go. It’s all about the player - intention is everything.

“I lost that simplicity and as soon as I got it back, I felt like I was 16 again. I was channelling 1968. People were telling were saying Plastic Hamburgers was too different and that I’d lose my listeners and I said, ‘Well, so be it!’ I come out with this riff that scared the shit out of some of these suits. But I won my Grammy without a label. You could see the look on people’s face when I was turning in songs like A Boy Named Andrew or my Chris Cornell tribute Dark Windows!

“I want to be free like Electric Ladyland or the White Album. I want to capture the feeling that contributes to a conversation, not owned by some corporation. We’re not afraid to speak or expand on it.”

Speaking of Chris Cornell, you toured with him a few times. What will you remember most about the man?

Chris Cornell was a wonderful human being with a great heart and a big smile. He was someone who wanted to help me out and didn’t want anything in return; he just believed in it

“I did three tours with Chris Cornell. One was in America and one in Europe, both of which were acoustic - the other was with my band opening for Temple Of The Dog [on the grunge supergroup’s 25th anniversary tour in 2016]. That guy was a blessing to my life; he saw me on YouTube and thought, ‘Man, he’d be perfect to tour with me…’

“I didn’t think he knew what he was talking about, I was afraid his fans might not be into my crazy shit and I was completely wrong. I gained so many of his fans that continue coming to my shows. He was a wonderful human being with a great heart and a big smile. He was someone who wanted to help me out and didn’t want anything in return; he just believed in it. He taught me that’s how you need to roll.

“I learned to forget the man in the ivory tower, sitting there in a repressed fantasy judging the world on how it should look or sound for his consumption machine… instead, help each other. Roll with the artists you love, say their names.

“There was no ego with Chris - he’d come into my dressing room just to say hi and check on me. He was gracious and giving. I met his kids and wife, he met mine… it was that type of deal. He was a beautiful person.”

The expanded version of Please Don't Be Dead (Deluxe) is out on 5 October via Cooking Vinyl and Blackball Universe.

Amit has been writing for titles like Total Guitar, MusicRadar and Guitar World for over a decade and counts Richie Kotzen, Guthrie Govan and Jeff Beck among his primary influences. He's interviewed everyone from Ozzy Osbourne and Lemmy to Slash and Jimmy Page, and once even traded solos with a member of Slayer on a track released internationally. As a session guitarist, he's played alongside members of Judas Priest and Uriah Heep in London ensemble Metalworks, as well as handling lead guitars for legends like Glen Matlock (Sex Pistols, The Faces) and Stu Hamm (Steve Vai, Joe Satriani, G3).

“He seems to access a different part of his vast library of music genre from the jukebox-in-his-head! This album is a round-the-world musical trip”: Joe Bonamassa announces new album, Breakthrough – listen to the title-track now

"The Rehearsal is compact, does its one job well, and is easy to navigate without needing instructions": Walrus Audio Canvas Rehearsal review