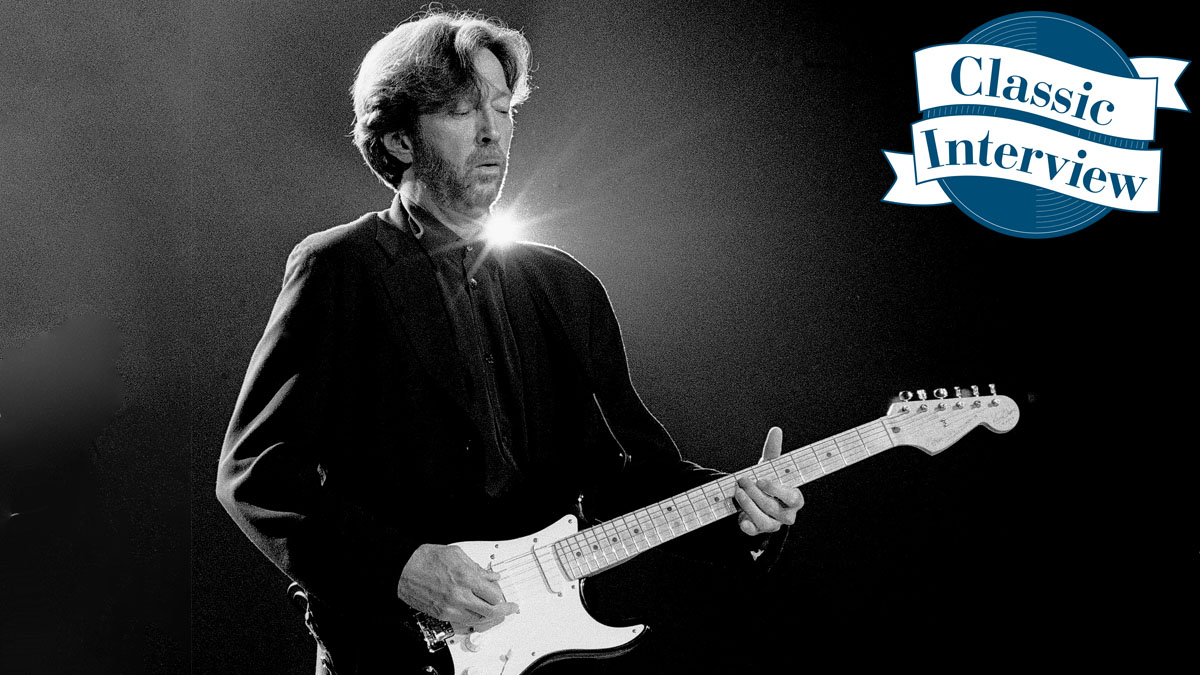

Eric Clapton on Robert Johnson: "When I was younger, Hellhound used to frighten me when I listened to it. The idea that he was really singing about being pursued by demons was too much for me – for a while I really couldn’t deal with it"

Classic interview: When Slowhand revisited Robert Johnson's legacy in 2004 we caught the bluesman in candid mode – "Robert Johnson wasn’t entertainment. When I first heard him I had a very hard time listening to him, because it demanded something of me"

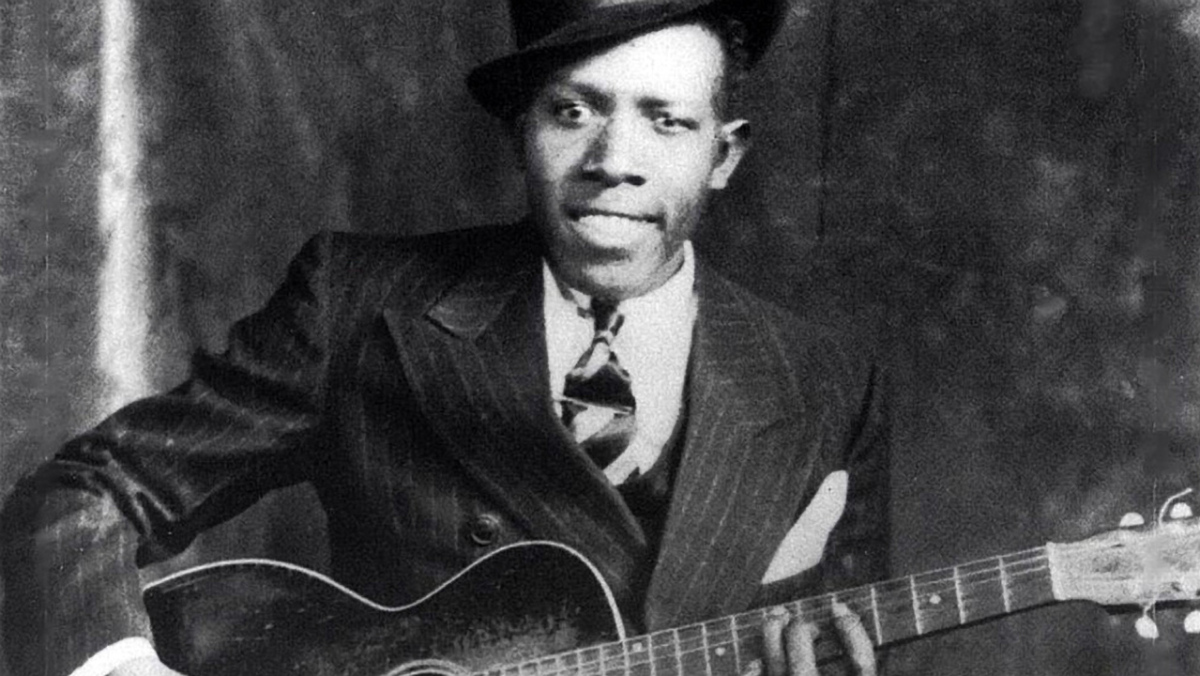

Classic Interview: "I’m not as intimidated by Robert Johnson as I was," Eric Clapton told us in 2004. Entering the studio at the start of that year, the plan had been to record new material. Instead, apparently struggling to come up with enough new, finished songs for an album, Clapton had started jamming on Robert Johnson songs... and ended up with a whole LP, Me and Mr Johnson.

Recorded in just two weeks with Clapton's AAA studio band, which at the time included Andy Fairweather Low, Billy Preston, Steve Gadd, Doyle Bramhall II, and Nathan East, the 14-track tribute is a collection of lovingly curated and performed Johnson covers.

When we caught up with Slowhand around the release, we found him in reflective mood. "In a way, I see Me and Mr Johnson as more of a tribute to my love of Robert Johnson than it is to Robert Johnson, if that makes any sense.”

How would you explain Johnson’s greatness to a blues novice?

“When I first listened to him I was completely overwhelmed by his vulnerability. What struck me more than anything else was how in touch with his feelings he was. That is something that’s taken for granted today – there are so many different ways these days to get in touch with your feelings, either through therapy or support groups. But back in the early sixties, when I first heard him, the culture in England and the US was much more repressed.

"There were very few people on record who sounded like they were singing from the heart, or knew who they were or what they felt. Most were just imitating other people or developing something for the stage. Music, for the most part, was very artificial. Even people I loved, like [the blues pianist] Leroy Carr or [Delta bluesman] Son House, still sounded like entertainers to me.

"Robert Johnson wasn’t entertainment. When I first heard him I had a very hard time listening to him, because it demanded something of me"

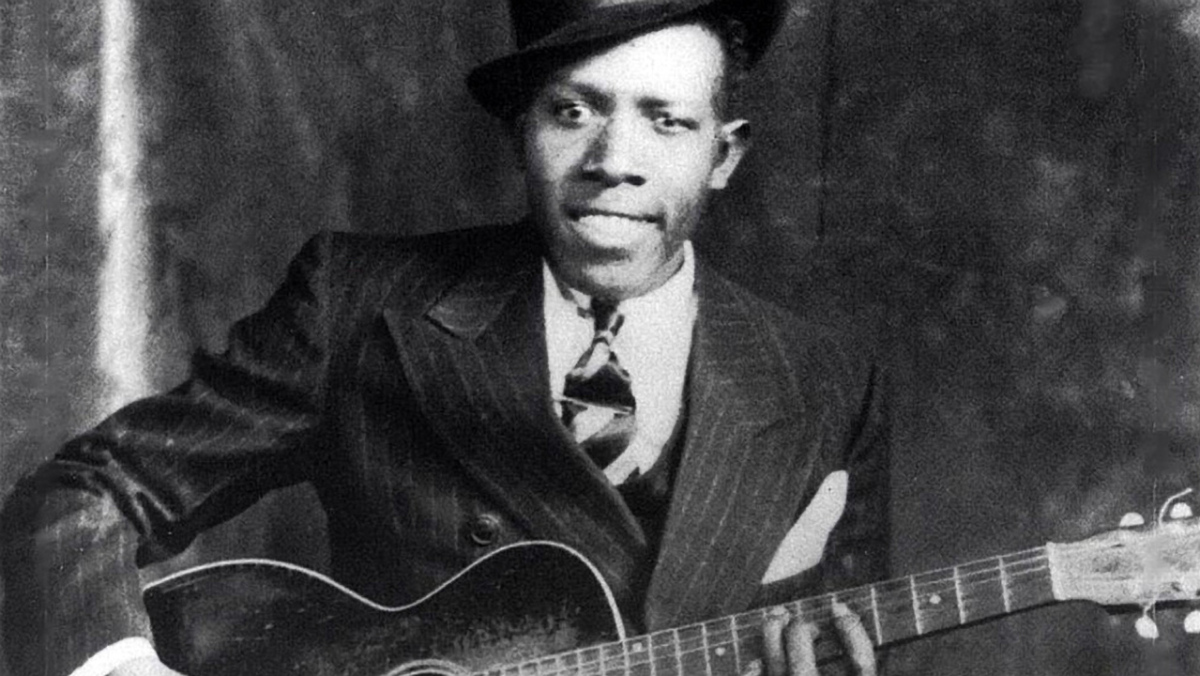

"Robert was something else – he sounded like he was naked. I don’t know if this is true or not, but it was reported by Don Law, the man who recorded him, that prior to one of his sessions there were some Mexican musicians in the room with him. It seems he couldn’t play in front of them – he had to turn and play to the corner of the room. And I thought, That makes sense. How could he play in front of other people when he’s exposing his emotions so entirely?

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“I’d never heard anyone do that before. All the music I’d heard up until that time was just pop music made for entertainment. Robert Johnson wasn’t entertainment. When I first heard him I had a very hard time listening to him, because it demanded something of me.”

What struck you most about him?

“It was the whole package. His guitar – especially his slide playing – was an extension of his singing. The slide part in Come On In My Kitchen is a great example of that. In fact, the one regret I have about my album is that I didn’t play a particular slide part of his on my version. I regret it because I think it would’ve been possible to do.

"There’s a part where Robert sings, Can’t you hear the wind howling? and follows it with a response with his slide, and it’s just like his voice. I thought to myself, I’m not going to do that, I just don’t think I can. I couldn’t allow myself to go there... and now I think I should’ve tried.”

Some blues revisionists, most recently the musicologist Elijah Wald, have tried to downplay Johnson’s importance as a blues artist, maintaining that his importance was a creation of his later, white audience. Others point out that a lot of his material was actually derived from previous work by House and other bluesmen like Lonnie Johnson and Kokomo Arnold. What’s your view?

“I recently read Elijah Wald’s book [Escaping The Delta: Robert Johnson And The Invention Of The Blues, Amistad Press], and he made what I thought were some pretty rash statements. One was that Robert could’ve been removed from the picture and nothing much would’ve been affected. I thought that was an extraordinarily hasty thing to say, and I’ll explain why.

"Nobody else from that period – not Son House, not Charlie Patton, not Blind Lemon Jefferson – played anything like that"

“Before I heard Robert Johnson, I had already been exposed to a lot of rhythm and blues artists like Chuck Berry and Jimmy Reed. As soon as I heard Johnson play boogie on things like When You Got A Good Friend and Ramblin’ On My Mind, I immediately understood where a lot R&B grooves originated. Nobody else from that period – not Son House, not Charlie Patton, not Blind Lemon Jefferson – played anything like that.

"I think that was Robert Johnson’s invention, which is a considerable contribution to the blues, and it enabled me to make a direct connection from Robert Johnson to Jimmy Reed.”

Johnson was once described as a “one man power trio” because of his penchant for simultaneously playing a bass line, a rhythm part on the middle strings and a lead riff on the treble strings – all while singing the song.

“Yes, it was a natural thing for him to do, and I think that’s also his invention. You mention that while playing a line on the low strings he would simultaneously pick little reference notes on the high strings – that’s something he does on When You Got A Good Friend.

"Well, Freddie King used to do that all the time, and I’ve heard countless electric guitar players do that. It was like Johnson was playing electric guitar before there were electric guitars. That’s the bizarre thing. And while I accept that he was a product of influences like Lonnie Johnson and Kokomo Arnold, I don’t think anyone summed up the whole Delta blues experience – or had the impact – that he did.”

"Hellhound... used to frighten me when I listened to it"

Does the Devil mythology associated with Johnson still hold any interest for you? Robert certainly sang about the Devil and hell in songs like Me And The Devil Blues and Hellhound On My Trail…

“More likely he was speaking about a girlfriend, or trouble in general. I think Hellhound On My Trail is like that. When I was younger, Hellhound... used to frighten me when I listened to it. The idea that he was really singing about being pursued by demons was too much for me – for a while I really couldn’t deal with it.

“Then I began thinking of it as a metaphor for trouble. I believe in the presence of evil. I think it’s possible to conceive of something so bad that it can lead into a whole other world – a world where there is little hope. And I think that’s what he was going after. And when he sang about the crossroads... the crossroads is about choosing which path to go down. It’s about the moral decisions you make every day.”

Is there anything else about Robert or his music that you didn’t get in your youth but now understand?

“When I was a teenager, I could take the music only in very small measures because it was so intense. But do I grasp it any better? I’d have to say that I don’t – it’s as mystical and as mysterious to me now as it ever was. I still don’t know how he did some of that stuff.

"Take Kindhearted Woman Blues. There’s an instance in one of the verses where he plays an odd single-note kind of accompaniment on the IV chord. I can’t do it – I can’t see how anybody could do it [laughs].”

What would you say distinguishes Robert’s playing from that of his Delta bluesman peers?

“He had finesse! I heard Johnson before I heard Son House and Charlie Patton, and people kept telling me I had to check them out. When I did, my first reaction was, Whoa, these guys are kind of noisy, they’re kind of clanky! Clumsy is probably too harsh of a word. But then I’d go back to Robert and I’d think, There’s no comparison, this guy’s got finesse. His touch was extraordinary. Which is amazing in light of the fact that he was simultaneously singing with such intensity.”

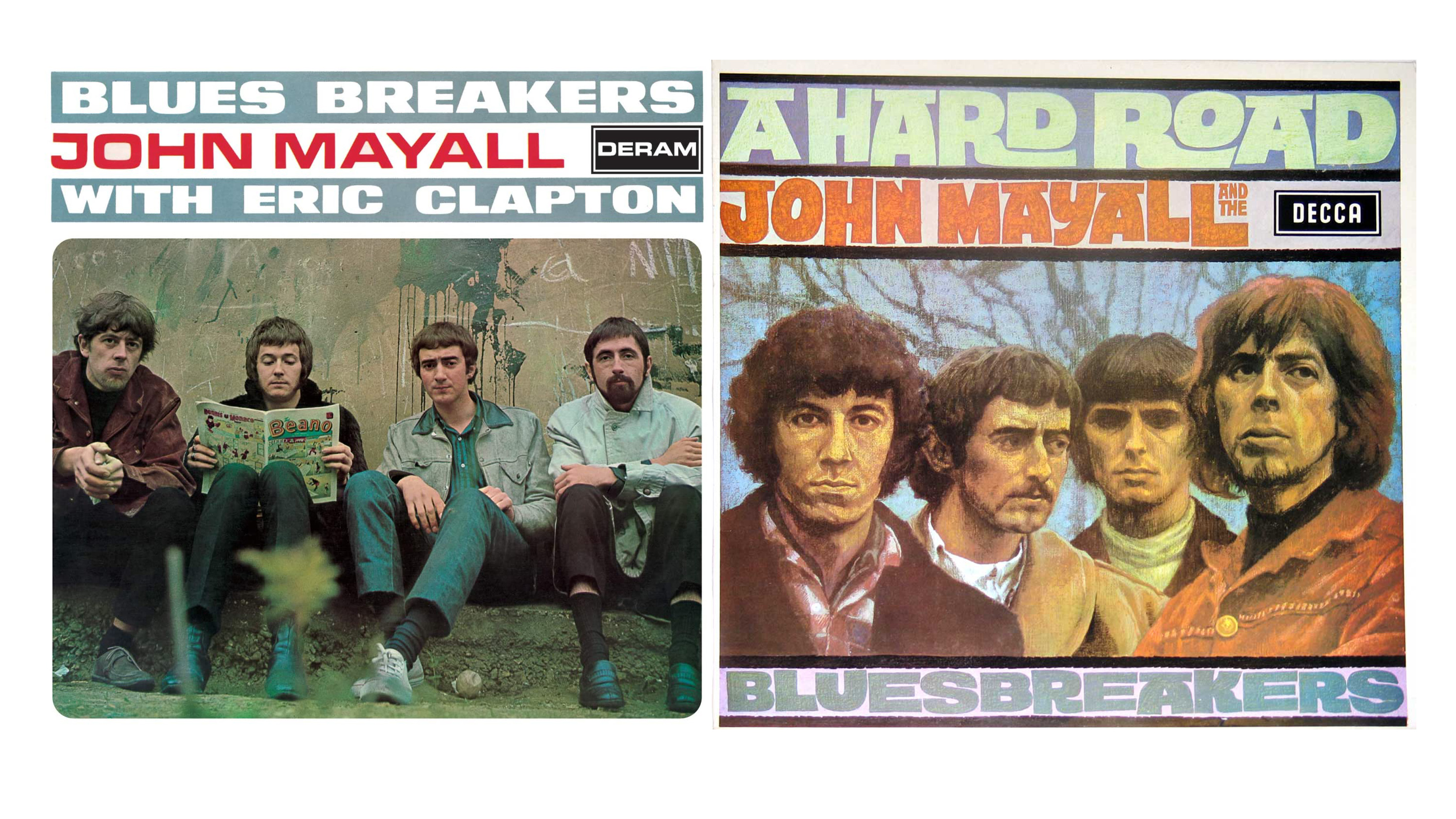

What do you think of your earlier interpretations of Johnson’s music, such as your version of Crossroads on Cream’s Wheels Of Fire?

“I don’t think about it at all [laughs]. I certainly put that one to bed quickly! I actually have about zero tolerance for most of my old material. Especially Crossroads. The popularity of that song with Cream has always been mystifying to me. I don’t think it’s very good.

"Apart from that, I’m convinced that I get on the wrong beat in the middle of the song, which often happened with Cream. It drives me crazy that there’s this performance of me floating around where I’m supposed to be on the ‘one’ where really I’m on the ‘two.’ So, I never really revisit my old stuff. I won’t even go there.”

What about your other covers of Robert’s songs?

“The version of From Four Till Late on Fresh Cream was probably okay, but I don’t think I’ve ever listened to my performance of Rambling On My Mind [Blues Breakers With Eric Clapton] that I did with John Mayall. I can’t even imagine what that sounds like.”

Well, then let’s talk about your current interpretations. Instead of solo guitar, you’ve arranged Johnson’s music for a complete band, and often completely depart from the feel of the original versions. How did you pick the songs?

“The album sort of came about by accident. I was working on an album of original compositions, and when the sessions started getting unproductive we would work on a Robert Johnson song to lighten things up.

"After a month, however, the work on my original music was going slowly, but we had almost an entire album of Robert Johnson songs finished! [Laughs] I figured, maybe this is what we should be doing.”

How did the band learn the songs?

“In many cases I’d play the original Robert Johnson track to the band. Then we would go out and play and record it. I would try to replicate the intros, but after that, it was every man for himself!”

Which tracks were the most difficult to capture as a recording?

“Last Fair Deal Gone Down was probably the hardest to do. It’s just plain weird. And as far as the lyrics go – one verse is almost complete gibberish. Hellhound... was hard too, but I think we did a good job on it. I had to enlist the other guys in the band to help me figure out the parts and how to count them. Our drummer, Steve Gadd, really helped me crack that song.

“When we did Come On In My Kitchen we couldn’t decide whether to do it as a shuffle or in straight rock time. So in the end we tried it both ways. We had the same problem with Milkcow’s Calf Blues. But that ended up being one of my favourite tracks because I feel we really cracked that groove wide open.”

Were most of the performances done live?

“Absolutely. Of course we baffled some of the instruments to minimise leaking, but we all played together in one room and did everything live, including the vocals. The only time we overdubbed was as a result of my own shortcomings.

"I think I had to redo the vocals on Last Fair Deal Gone Down and Stop Breaking Down. At least 10 of the tracks are totally live.”

Little Queen Of Spades is intriguing, vocally – it’s one of the only tracks on the album where it sounds like you are really trying to imitate Robert’s singing...

“It was easier to allow myself to emulate Johnson there because we had abandoned the rest of his arrangement on that song. I completely threw out the guitar arrangement on that one and let the band play it like we were in a bar.

"My concept was, You guys don’t know this song, so all that’s left are the words and the vocal melody, so I’ll hold it together that way. So I sang as close as I could, in a relaxed way, to the original version.”

I’ve never actually sat down and played Robert Johnson unaccompanied

Why did you choose not to record record any of the songs solo acoustic?

“I tried to do Terraplane Blues solo acoustic and it just sounded weak.”

When did you learn to play Robert Johnson’s music on the acoustic guitar?

“To tell you the truth, I never really did. I’ve never actually sat down and played Robert Johnson unaccompanied. Even when I played Malted Milk on Unplugged, I did it as a duet with Andy Fairweather Low. I can play pieces of Robert Johnson songs, but not entire tunes note-for-note.

“I can play Big Bill Broonzy’s stuff, but there’s something very symmetrical about his music. Once you learn the fingerpicking pattern, it’s easy. But Robert’s music is so asymmetrical, and there is always something new going on. I find it very difficult to play by myself.”

Back in the early sixties, when you were playing with the Yardbirds, you worked with Sonny Boy Williamson II, who knew Robert Johnson. Did you ever ask him about Robert?

“No, partly because we became enemies on the first day we met. I went up to him and asked, Isn’t your name really Rice Miller? Of course, his name really was Rice Miller. I must’ve come off like some naïve blues collector. And our relationship never recovered after that. I think he thought I was making fun of him. Sonny Boy was a very difficult and strange man.”

You don’t want to make it a mission, but you have to make sure that nobody forgets completely

You’ve been directly influenced by several key mentors in your career, and you regarded Muddy Waters in that way. Do you feel any personal obligation to pass your knowledge down to younger guys like Doyle Bramhall II?

“I’ve always run away from that responsibility. But when all the original blues guys are gone, you start to realise that someone has to tend to the tradition. You don’t want to make it a mission, but you have to make sure that nobody forgets completely.

I just play what I play, and every so often make a blues-oriented album like this one and hope people pick up on it. I’m sure I’ll do another one with somebody in the future, and in that way I feel like I’ve done my part. I recognise that I have some responsibility to keep the music alive, and it’s a pretty honourable position to be in.”

What specifically did you learn from playing with guys like Muddy Waters, Buddy Guy and BB King?

“I’m always aware of the authority they carry, and it is immense. If the blues community is an army, then these guys are generals. It’s just acknowledged when they walk into a room. Muddy just carried a power that everyone was in awe of. And it’s the same with Buddy and BB – it’s almost like they are kings.”

The new album features two other guitarists, Andy Fairweather Low and Doyle Bramhall II. How did you divvy up the parts among the three of you?

“I’ve been working with both guitarists for a couple of albums now, so we’ve developed an intuitive working relationship. I made a few decisions about how I was going to approach the guitar on this album and the arrangements grew out of that.

"Since I also had to sing and knew the music the best, I decided I was going to be the foundation and play as a straightforward accompanist. I played this whole album with my fingers instead of a pick, and deprived myself of my natural attack.”

5 ways to play like Robert Johnson without making a deal with the devil

How did you enlist Doyle in your band?

“I first heard him through his manager, who is a friend of mine. He sent me this album by Doyle called Jellycream, which I thought was an astonishing record. It’s always nice for someone who has been around for as long as I have to hear someone who’s relatively young who’s adding something, but still has a connection to past traditions.

"I asked him to play on my last two albums, Riding With The King and Reptile, and soon he just became part of the team and the fabric.

“I’m particularly a fan of his slide playing. He’s one of the only guitarists I know who can sound like Hop Wilson, a guy from Houston who played lap steel but sounds something like BB King. Very few guitarists play like him, or even know about him, but Doyle was taken with him and I always try to get him to do his Hop thing somewhere on my albums.

What is more important to you these days, playing the guitar or singing?

“Let me answer that this way: if we had instruments in this room, the easiest thing we could do is play a 12-bar blues. It’s the most common denominator. The next thing you’d have to ask is whether we’re going to just play, or is somebody going to sing?

"When you add a singer, that’s when the music gets serious; the rest is just playing around. I’ve been in those situations and the whole energy changes. It goes from just a jam to a genuine mission...”

5 songs guitarists need to hear by… Eric Clapton (that aren't Layla)

“Beyond its beauty, the cocobolo contributes to the guitar’s overall projection and sustain”: Cort’s stunning new Gold Series acoustic is a love letter to an exotic tone wood

Guitar Center’s massive Guitar-A-Thon sale has landed, and it includes $600 off a Gibson Les Paul and a host of exclusive models from Epiphone, Taylor, and more