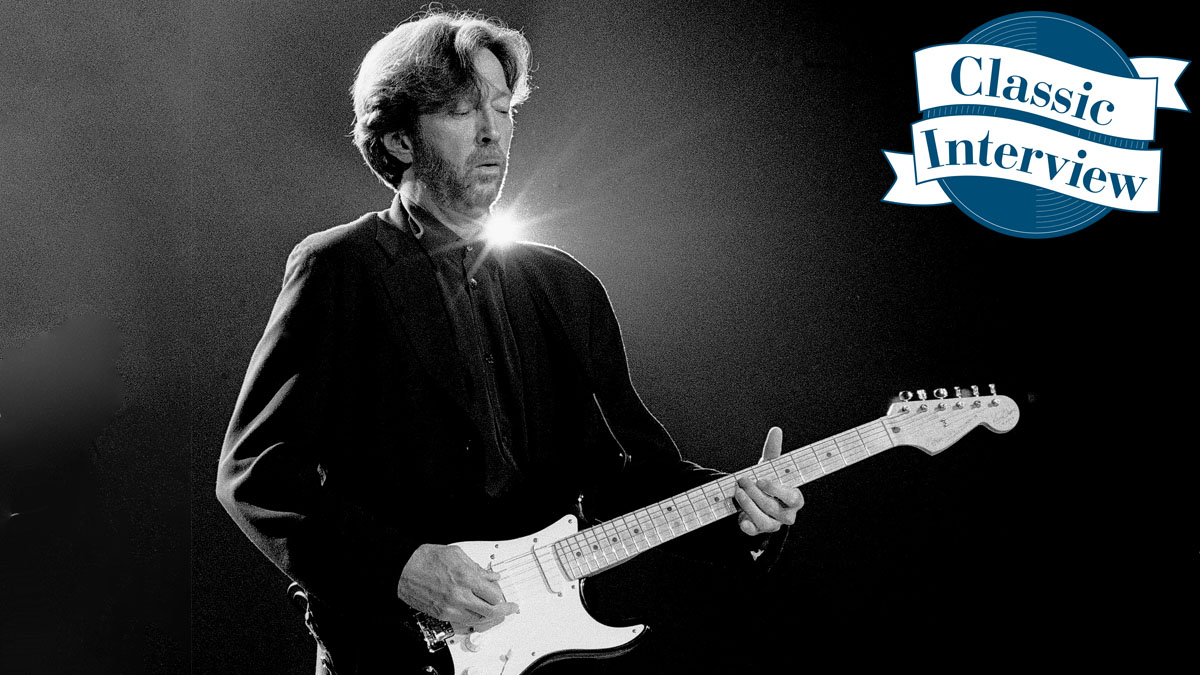

Classic Interview: Eric Clapton – “I was in it to save the world. I wanted to tell the world about blues and to get it right. In a way I thought, ‘Yes, I am God; quite right!‘“

In this Guitarist interview from 1994, Slowhand looks back on the early days with John Mayall, The Yardbirds and Cream, and explains why blues was the only education he needed

This classic Guitarist interview from 1994 captured the guitar god in reflective mood for cover of the magazine's landmark 10th Anniversary Issue. From The Cradle, his follow-up to the Unplugged, was recorded and awaiting release, and that collection of blues covers set the tone for the conversation.

Here we find Clapton explain how the blues was more than a sound to him. It was a historical endeavour as much as anything, a process of peeling back the influences of those who went before him – to the players who were his heroes' heroes, and taking it right back to the source. This, he explains, is an essential process for any player looking to master a style and make it their own.

But he also talks about the tumultuous times as he made his name on record, with John Mayall, The Yardbirds and Cream, his journey on the electric guitar, and a lot more besides. Enjoy!

Your career has spanned more than three decades now, covering a variety of different genres and involving some of the most prominent contemporary musicians of the late 20th Century. Can you remember what it was that turned you on to music in the beginning? What was it that made you want to be a musician and who were the people who most inspired you?

“Well, the first thing that rang in my head was black music; all black records that were R&B or blues oriented. I remember hearing Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, Big Bill Broonzy, Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley and not really knowing anything about the geography or the culture of the music. But for some reason it did something to me – it resonated.

“Then I found out later that they were black and they were from the Deep South, and that started my education. In fact the only education I ever really had was finding out about blues. I took a kind of elementary fundamental education in art, but it didn't rivet my attention in the same way blues did.

"I was in it to save the world. I wanted to tell the world about blues and to get it right."

“I wanted to know everything. I spent all of my mid to late teens and early twenties studying this music; studying the geography of it, the chronology of it, the roots, the different regional influences, how everybody inter-related, how long people lived, how quickly they learnt things, how many songs they had of their own and what songs were shared around...

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“I mean I was just into it, you know? I was learning to play it as well and trying to figure out how to apply it to my life. I don't think I took it that seriously, because when we're young we don't; it was only when other people showed an interest that I realised that I could make a living out of it.“

What about the guitar, though? When did you first hear the instrument and think to yourself: "That's what I want to play?"

“I think on the early Elvis records and Buddy Holly - when it was clear to me that it was an electric guitar, then I wanted to get near it. I was interested in the white rock 'n' rollers until I heard Freddie King - and then I was over the moon. I knew that was where I belonged - finally. That was serious, proper guitar playing and I haven't changed my mind ever since.I still listen to it and I get the same boost now that I did then.“

What was it like for you when you started playing in clubs for the first time and what was the general standard of guitar playing like then?

“Well, anybody that had any idea of how to play any instrument could just about hold their own because there was no competition; there was no one around. There were only a handful of bands, and anyone that could play Sam & Dave, Stax and Motown was a master.

I grew up playing in clubs – that's my spiritual stomping ground

“I came from the blues, so to my way of thinking I had a grasp of that kind of thing. To my reckoning R&B came from the blues so I felt I was in some kind of inner sanctum, mentally or spiritually. If you could play anything in a halfway convincing fashion you were the boss and there were so few of us.

“And if you were pretty good, you could work all the time and get fairly well paid; you were successful.“

Do you harbour any romance for that period at all? Was it Mark Knopfler who said that in some ways he misses the old days where you could turn up at a club with an amp and a guitar and just do a gig?

“Yeah, that's true, although I don't picture myself doing that these days. It's funny for me now to think of walking into a club and seeing another band play. I do it every now and then and it all comes back to me and I feel like this is where I belong. I mean, I grew up playing in clubs – that's my spiritual stomping ground.“

Let's talk about the whole ‘Clapton is God‘ thing that happened during the late 1960s. Were you uncomfortable with that?

“I thought it was quite justified to be honest with you. [Laughs] I suppose I felt I deserved it for the amount of seriousness that I'd put into it. I was so deadly serious about what I was doing – I thought everyone else was either in it just to be on Top of the Pops or Ready Steady Go, or to score girls or for some dodgy reason.

“I was in it to save the world. I wanted to tell the world about blues and to get it right. Even then I thought that I was on some kind of mission, so in a way I thought, ‘Yes, I am God; quite right‘. My head was huge. I was unbearably arrogant and not a fun person to be around most of the time because I was so superior and very judgmental. I didn't have time for anything that didn't fit into my scheme of things.“

People assume you were with The Yardbirds or The Bluesbreakers for a long time, but it was a matter of months in both cases…

“I went through all those things very quickly. I mean, Cream was like a year and a half, and even with John Mayall, I was only half there. I was so unreliable, so irresponsible. I would sometimes just not show up at gigs and that's how Peter Green was asked to play with John – because I wasn't there.

“I went to see John last year [1993] to actually make amends; I looked back and realised how badly I'd behaved.“

Cream was meant to be a blues trio, yeah. I just didn't have the assertiveness to take control. Jack and Ginger were the powerful, dominant personalities in the band

How does Cream fit in to your perspective? It must have been a very intense 18 months?

“It was very intense and it actually seems like we were together for three or four years. My overall feeling about it now is that it was a glorious mistake. I had a completely different idea of what it would be before I started it and it ended up being a wonderful thing, but nothing like it was meant to be.“

It was meant to be your band, wasn't it?

“It was meant to be a blues trio, yeah. I just didn't have the assertiveness to take control. Jack and Ginger were the powerful, dominant personalities in the band; they sort of ran the show and I just played. I just went with the flow in the end and I enjoyed it greatly, but it wasn't anything like I expected it to be at all.“

In the Cream period you virtually ran the whole gamut of Gibsons: your Firebird, 335, Les Pauls, SGs – the very famous psychedelic SG. Were there any particular favourites?

“I've still got that 335 and I love it – I still get it out every now and then. The 335 was a big favourite and that particular Firebird, I had some great times on that; the single pickup produced a fantastic sound.

“I think that SG went through the Cream thing just about the longest, it was really a very, very powerful and comfortable instrument because of its lightness and the width and the flatness of the neck. It had a lot going for it – it had the humbuckers, it had everything I wanted at that point.“

Looking back now, are you able to put all of your early stuff into context objectively? Can you look back at the player you were then and think, “Yeah, that was okay“, or, “That was a bit dodgy?“

“Yes, fairly. I think all of it was okay until drugs and drink got involved. I don't think my facility as a player has really got much better or worse. I mean, I've just finished doing a blues tune, a Freddie King song, and it doesn't sound that much stiffer or that much faster than when I was doing John Mayall or Cream – a bit more fluent, a bit more confident maybe.

“But what's clear to me is that then I was much more in touch with the actual making of music – as I am now – and there was this long bit in between where I was more inclined to just get out of it. It was at some point towards the end of the sixties and all the way through the seventies – I was out, you know? I was kind of on holiday, and being a musician was my way of making the money to be on holiday.“

You toured a hell of a lot in the seventies…

“Toured and recorded and got out of it. I had a great time, but it was all fairly directionless. I mean, I don't regret any of it. To be honest, I think there was no other way for me to go, in a way. I'm just very grateful that I survived it and didn't die because I was often in some very seriously dangerous situations with booze and drugs.

By learning too much from the later players, you don't have that much opportunity to make something original.

“I used to do crazy things that people would bail me out of and I'm just grateful that I survived. But the music got very lost; I didn't know where I was going and I didn't really care. I was more into just having a good time and I think it showed. I think I got fairly irresponsible and there were some people who liked it and others who got very pissed off.“

That period ended dramatically around 1984/85. Suddenly there were projects like Edge Of Darkness and the Roger Waters album The Pros And Cons Of Hitch Hiking, but it was probably Live Aid that was responsible for re-establishing you in many people's minds. Did the reaction surprise you?

“Yeah. I'm not sure even I was able to take it all in. I've always been a very, very self-effacing or low self-worth sort of person. When they told me where I was on the billing I didn't get it – I thought, ‘What? Really?‘ That did a lot for me.

“And that reception – it was mindblowing. From that point I started to give myself a bit more of a pat on the back and be kind to myself.“

Do you have any advice for today's players?

“Yeah – listen to the past. I've run into a lot of players in the last 10 or 15 years who didn't really know where it was coming from. They thought it came from Jimmy Page or they thought it came from Jeff Beck or they thought it came from Buddy Guy or that it came from BB King.

“Well, it comes from further back and if you go back and listen to Robert Johnson, Blind Blake, Blind Boy Fuller, Blind Willie Johnson and Blind Willie McTell, there are thousands of them who all have something which led to where it is now.

“The beauty of it is that you can take one of those things and make it yours. But by learning too much from the later players, you don't have that much opportunity to make something original.

“I listened to King Oliver and I listened to Louis Armstrong, Jelly Roll Morton, Thelonious Monk, Charles Mingus, John Coltrane, Archie Shepp… I listened to everything I could that came from that place that they call the blues but, in formality, isn't necessarily the blues.“

Guitarist is the longest established UK guitar magazine, offering gear reviews, artist interviews, techniques lessons and loads more, in print, on tablet and on smartphones

If you love guitars, you'll love Guitarist. Find us in print, on Newsstand for iPad, iPhone and other digital readers

“Every note counts and fits perfectly”: Kirk Hammett names his best Metallica solo – and no, it’s not One or Master Of Puppets

“I can write anything... Just tell me what you want. You want death metal in C? Okay, here it is. A little country and western? Reggae, blues, whatever”: Yngwie Malmsteen on classical epiphanies, modern art and why he embraces the cliff edge