Emvoice One is here, and it promises to be ‘the world’s most realistic vocal synth plugin’

A virtual singer that you’d actually want to use?

Cracking vocal synthesis has been a goal for many a plucky plugin developer, but so far, none of them has really been able to do it. As such, there’s bound to be plenty of interest in Emvoice One, which is billed as “the world’s most realistic vocal synthesizer”.

We first got word of this in April, and it’s since been honed during a period of beta testing. You can download the Emvoice One plugin for free; this comes with a limited number of notes so that you can test the software, but if you want to use it properly, you’ll need to purchase Lucy, the first voice package, for $199.

Rather than using modelling and synthesis techniques, Emvoice One is based on deeply sampled human performances, breaking these down to the granular level. It features individual phonemes recorded at multiple pitches - when you’re using the software, samples are reconstructed by a cloud-based engine and sent back to your DAW.

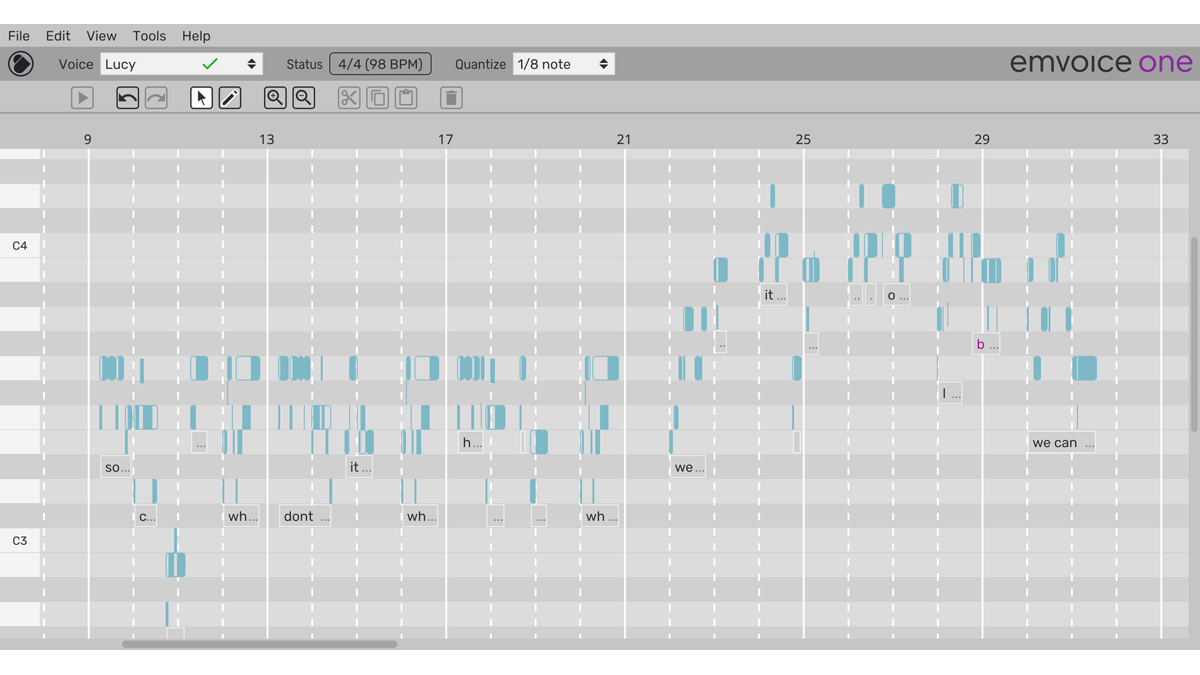

Fortunately, users are shielded from a lot of the complex processing, and you can operate Emvoice One via a familiar DAW-style piano roll editor. This enables you to add notes and to type in lyrics, as well as program glissando and vibrato patterns. There’s a two and a half octave vocal range running from E2 to A4.

You can choose from various pronunciation options or create your own words from phonemes, so Emvoice One should be as straightforward or as flexible as you need it to be.

Emvoice One runs on PC and Mac as a VST/AU plugin (an AAX version is coming soon) and you can find out more and download it on the Emvoice website.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

I’m the Deputy Editor of MusicRadar, having worked on the site since its launch in 2007. I previously spent eight years working on our sister magazine, Computer Music. I’ve been playing the piano, gigging in bands and failing to finish tracks at home for more than 30 years, 24 of which I’ve also spent writing about music and the ever-changing technology used to make it.

![PRS Archon Classic and Mark Tremonti MT 15 v2: the newly redesigned tube amps offer a host of new features and tones, with the Alter Bridge guitarist's new lunchbox head [right] featuring the Overdrive channel from his MT 100 head, and there's a half-power switch, too.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/FD37q5pRLCQDhCpT8y94Zi.jpg)