Ela Minus: “The more you edit the more you kill the soul of your music"

Ela Minus’s debut is inspired by creating simple human interactions with technology

After studying jazz drums and music synthesis at Berklee College of Music, Ela Minus found her dream job when hired by instrument manufacturer Critter & Guitari to test, assemble and design their latest range of synths.

Tired of the modern laptop-driven approach to recording and live performing, Ela embarked on a mission to bring back the simplicity and authenticity she felt was missing from electronic music.

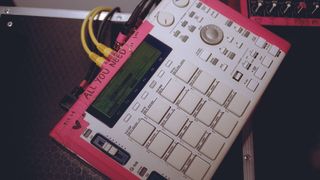

Led by her trusty Akai MPC1000, the producer focused on building a toolbox of instruments that could be perfectly replicated on stage, enabling her to formulate ideas for future recordings while performing live. Her debut album, fittingly titled Acts of Rebellion, embodies Ela’s headstrong ideology and intuitive approach to music-making that conveys genuine emotional resonance.

You were originally a drummer and multi-instrumentalist, so what sparked your interest in making electronic music?

“I got a scholarship to go to Berklee to learn jazz drums and music synthesis and while I was there began thinking I should do something else with my life other than just play drums. I was very much a fan of Radiohead and Kraftwerk and loved electronic music and going to clubs, so I decided I wanted to learn coding and understand how to program software synths.”

Did you get what you wanted from Berklee or was there too much music theory involved?

“I actually hated it and had a very weird experience. Out of everyone I met on the course I was the only one who graduated because they would get so frustrated and drop out. I was very young and had never studied before, but that was a challenge to me and I have this personality where I like to overcome a challenge, plus I knew if I dropped out I would have to get a job doing something outside of music.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

"The music synthesis course was even more frustrating because it was completely designed for people that wanted to be DJs or produce for other people. I just wanted to learn synthesis.”

You mentioned Kraftwerk, who have a very clinical sound, yet you found an emotional connection to their music?

“It’s interesting that you find them clinical. I guess they are, but for me it’s about their use of melodies and pop song structures. They have certain songs where the melodies live with you forever, and that’s where I get the emotional connection.

"I resonate with melodies and chords more than anything, so even though I love techno and colder rhythmic-based genres, I would normally never listen to that at home. The moment Kraftwerk entered my life it was as if someone showed me a combination of those two worlds - really technical electronic music and songwriting that had melodies and lyrics.”

Can producers learn from Kraftwerk’s approach by focusing more on subtracting than adding?

“That’s what I feel! When I’m working, I have four post-it notes around my monitors that say ‘mute’. I always find that muting is the key to everything and you should do it as much as you can.

"Before I started on this solo project I was craving to hear artists go back to that simplicity. It’s way harder to do, but what comes out of that is ‘soul’ - you can actually hear the artist. You hear a lot of music that has this wall of sound coming through you. It’s as if you’re staring at a landscape that has an aesthetic appeal but it’s not really saying anything and you can barely hear the person behind it because everything’s buried under layers of effects.”

Is modern technology partly to blame for leading producers down this path?

“The introduction of laptops, computers and overdubbing has a lot to do with it. In the ‘80s, if you were making electronic music you had to be able to play and record it live. You couldn’t just write MIDI in Ableton, send it to a thousand different synths and see which one you liked best.

"When I started this project, that’s what I was thinking about the most - I wanted to make electronic music how they used to do it, as a band with one synth for basslines, one for chords and one for melodies, and I wanted to play it all live. I only recorded multitracks because I wanted to get a wider stereo sound, but I didn’t add or edit anything and my sessions are ridiculously small.”

Do you think there’s a tendency to over-edit simply because the tools are available to do so?

“The more you edit the more you kill the soul of your music. You can edit anything to be beautiful if you really spend time with it, but I question why I am making music and what I want to say.

I’ll record something, improvise and listen back to see if I feel something in my stomach. If I don’t feel anything I throw it in the garbage, but if I do feel something I put my producer hat on and ask what it is that is waking up these feelings. Sometimes it’s really specific, like a synth line or vocal melody, so I’ll make a decision that everything should serve that because it’s the soul of what I just made.

"In my opinion, that’s when the magic happens and you don’t have to have rules about editing for the sake of editing. It’s like grooming - your face is nice so you can accentuate it with makeup, but you don’t have to plaster your face.

"I also feel the same about mixing. People mix as an art form, but there’s no song in there, it’s just an amazing mix. As producers, it’s easy to get confused about what our job is.”

Do you think there’s any difference in how male and female producers tackle those aspects of production and mixing?

“One of the things we’re missing out on is the differences between men and woman. Women are more emotional and practical; there is less bullshit [laughs]. Maybe it’s because we’re wired to be mothers and so our instincts are to survive and be more sensitive to what really matters. Maybe we put more heart into the music and there’s less showing off, which is quite common with men who make electronic music.”

Your fascination for making electronic music was sparked when someone gave you a Pocket Piano synth?

“It definitely sparked my fascination for hardware synths. I was frustrated with laptops because I’d spent two years coding and programming and my ear would just recognise laptops. I would go to shows and hear the fucking laptop at every show I went to, and before the Pocket Piano came along I couldn’t find a synth that was fun or inspiring. I got one for my birthday and thought this is the type of synth I want to build.”

After graduation you worked at Critter & Guitari. How did you get that job and what was your role at the company?

“It’s a tiny company - two guys own it and they had just one employee and hired me. For the first year I was assembling the synths and testing, but we all did everything and they taught me a lot. By the second year, I was helping them to design and think about new synths - the second synth we made was the Organelle. I knew how to program pure data so I was very involved in birthing that synth, testing, assembling and fixing the ones that were broken and shipped back.”

To what extent does understanding what’s under the hood make it easier to get the most of out of the technology you’re using?

“I’m not sure because when I’m making the music I’m not thinking about technical things because it’s a very playful and intuitive process. I guess having that knowledge spikes in when something goes wrong; for example, when playing live. Otherwise, having that knowledge probably makes me feel closer to the machine emotionally, just like when you know someone really well you feel closer to them.”

Does the circuitry of the older synthesizers have particular appeal to you?

“Yes, they’re very different and have an appeal to me. I wish I had more vintage synths, but they’re usually more expensive and it’s hard to get the good ones. I still don’t think FM synthesis has got better since the Yamaha DX7 and DX100 - those are my favourites. I have the DX100 and the TX7, which is a cheap module version of the DX7.”

What about FM synthesis appeals to you?

“It’s so deep and the synthesis is so complex. So much goes into them, but at the same time I really don’t like the new ones. I tried the Elektron Digitone but the machine is so complex that it’s hard to be musical with it. I still use the DX100, but only the presets. When those people were using and designing synthesisers in the ’80s and ’90s, they were thinking of music, songs and bands - it was about instant music-making, not sound design.”

Would you like to build your own synth?

“I’ve had many ideas in the past but as I’ve not worked in that industry much lately my brain may be a little rusty. I always wanted to make a sequencer with Latin American rhythms – one that’s as easy to use as a European sequencer like the Elektron Analog Rytm, which I’m absolutely in love with, but has more flexibility and subdivisions to make different polyrhythms.”

Yamaha DX100

“I love the sound of this 1985 FM synth. It’s extremely limited, which I like, and I always seem to find a sound that fits perfectly.”

Roland Juno-60

“It’s the only ‘real-size’ synth I own. Even though it has a very recognisable sound it’s very flexible once you get to know it. I essentially live in a cloud with an arp from the Juno.”

Moog Sirin

“The Moog Minitaur has been my bass synth for years but I always dreamed of having the same synth available in higher octaves so I could use it for melodies too. The Sirin is literally a dream come true.”

OTO Biscuit

“This is such an interesting machine because it adds so much depth to everything. I love detuning synths, bit-crushing drum machines and using the filter for… everything!”

Elektron Analog Rytm

“I love this drum machine. The combination of analogue synthesis, a sampler and a sequencer that is so musical is great.”

Acts of Rebellion is your debut album. Did you have a strong idea of the type of album you wanted to make?

“Because I improvise so much I try to start with a blank slate and write a couple of intentions, but when I was making EPs my idea was just to bring light to the people that listen to it. For the album, I’d been touring for a long time and wanted to make something that could be played live in small clubs. Subconsciously, I had all these other themes and little acts of rebellion.”

Does the title refer to your rebellious nature?

“That’s the logical conclusion, yes. Acts of Rebellion was the name of one of the songs, but I was very confused about where the title came from. Even more than my music, my character up until now has been very rebellious and a lot of things I’ve done in my life have been because somebody told me I couldn’t do them. For example, not using laptops – it would be way easier for me to produce that way but I won’t do it because everybody’s doing it.”

The Akai MPC1000 is the brain of your setup. What was the reason behind that choice?

“I bought it for $100 when I was in Boston because I wanted to fix it and see how it works inside, and it’s never failed me. I mainly use it as a MIDI sequencer. That’s why it’s the brain because I record all the MIDI tracks into it and he’s the one sending the MIDI to all the other synths.

"I also love the sampling aspect of it and obviously use that in a more traditional way, but I just find that it’s so musical and intuitive. I love that you don’t have to make it quantise, so it’s so easy to just play with and it’s so loyal to what you’re playing on your groove. I can also load up the next sequence while playing the one before, so I can play tracks live sequentially.

"Most of my music comes from the live shows. I leave space for very small four or eight-bar sequences and improvise on top. Usually after a night of playing live, if I like what I played I’ll save those sequences, get home and cue them up, and that’s always where my songs come from.”

So you’re effectively formulating ideas for new songs while playing live?

“Exactly that. A while ago I got a Squarp Pyramid sequencer because I’ve been craving sequencers that have a bigger range of possibilities. The Pyramid is amazing but you can’t keep playing it like you can with the MPC, which just makes me love it more.”

Do you ‘play’ your instruments in the traditional sense of the word?

“I don’t use that many samples so everything is synth-based. I play on a keyboard, record the MIDI into the MPC and send that to the actual synths when I’m recording and playing live, so except for a couple of technical things the sound source is always the synths and not the samples.

"For example, at the moment I don’t have a polyphonic synthesiser in my live set but do have the Roland Juno-60 at home, so I’ll record that into the MPC and those sounds are sample-based.”

What’s behind your choice of drums and beats?

“The Elektron Analog Rytm is the only drum machine I’ve ever owned and it’s still used for everything. I download sample packs sometimes to make new sounds but love the sequencer on the Rytm.

"As a drummer, I found it was so freeing - I could program whatever I want into it and every single step on the sequencer can be adjusted and automated which makes it sound extremely musical. All my beats are extremely simple. I’m always thinking about the least I can do with a beat and like to create something really minimal with just the kick, snare and hi-hat.

"Even though the Rytm is not a sample-based machine, you can add samples and it’s a synthesiser. I love the one-note-per-function thing - the machine is designed to have one synth machine for kicks, a different one for snares and another for hi-hats. I find that if I hear a kick I can make it with the synthesis because I have everything at my disposal to make the sound I want.”

You’re using some modular gear for effects?

“My Eurorack setup is simply a Make Noise delay, so I’m using guitar pedals for a lot of the effects. It’s really just a Strymon BlueSky Reverberator, which is really cool because it has a spring and a shimmer effect. I also found a plugin from Soundtoys called MicroShift that makes everything sound really wide, especially when I record a synth line with a lot of attack through the spring reverb.”

You seem to rely on a moderate amount of gear and look to get the most out of it?

“When I started this project I only had the MPC, Analog Rytm, Pocket Piano and the Moog Minitaur. The Minitaur is important to mention because all of my bass comes out of it. Then Moog gave me the Sirin as I was asking them like crazy to make something like the Minitaur for higher octaves.

"Because they’re analogue and have the same engine I feel they go well together and that was the key for this album because it made things even simpler. I was essentially sending the same line to both of them and able to double up in different octaves.”

Do you think your setup will inevitably change as you move forward and look for different ways to expand your musical vocabulary?

“It’s a question I’ve been asking myself because I really want to make a second album now. Once the record is out I’m going to shut my phone off and start working on it.

"I don’t have any new gear at the moment; I was staring at my synths last week and thinking about that, but it’s hard to make any decisions before I start writing. For me, the most important thing is the emotion rather than the actual writing, so everything else is secondary.

"In my mind, I would love to make a completely different album with the same machines. That would feel like an accomplishment because I’m the one making the music so it’s not about the gear.”

Do you think there will be a time when you embrace software, simply out of curiosity?

“There will be a day, but I don’t know if I want to do that by myself. I think there will be a point where it will be interesting to collaborate with people I like who can teach me about software. I already learn so much from talking to certain musicians that I meet at shows. I really don’t want to be known as a hardware synth artist, I want to be known as an artist – period. Again, it’s about using whatever serves the music best.”

“The more you think, the more ego gets involved, so I make the process really fast”

When do the lyrics enter your compositions?

“As mentioned, I’ll usually start improvising out of the loops I come home with after playing live. Then in the studio I’ll start playing as if I was playing live and make a stereo out to keep a recording of it. Sometimes, I’ll hear a melody in my head and start singing whatever I’m hearing, and I’ll try to keep that even if it’s silly.”

Do you keep it because you want to preserve your intuition?

“I’m trying to be as honest as I possibly can. The more you think about things, the more the ego gets involved, so I try to make the process really fast and commit to initial ideas whether my ego is saying something is good or a stupid sentence.

"With the lyrics, I usually take that first phrase, word or sentence and start repeating it and improvising from that. It doesn’t always work, but it helps me work on the form of the song and then I’ll sit down and write the rest based on those initial ideas or whatever I think I meant.”

What’s the meaning behind the track title Let them have the internet?

“Like many of us, we’ve gone through stages of love and hate with the internet. It was amazing before it started to become this big thing and I remember reading books by MIT coders explaining how it came to be and how the cyberpunks dreamed of the internet being a utopia, free of capitalism.

"Now what we have is the complete opposite. Everything we do is mediated by corporations including our bank accounts and communications - the definition of a capitalist society. At first, I thought this fucking sucks, but it’s also kind of nice because everything is on the internet and if we turn our cell phones off then what we have left is utopia because nobody is selling us anything or mediating. So I wanted to say, let them have the internet and we can have real life.”

Would you say that the track Tony is also about how technology interferes with our human-to-human interactions?

“I clearly love the concept of technology, but I’m against the way we’re using it. I read a book called What Technology Wants and remember how it made me think about how humans have been obsessed with human relationships and socialising since forever. Gossiping is a big part of human evolution. What I don’t really like is how we’re using all of this technology in order to socialise. We’re obsessed with getting ‘friends’ when that should be done in our physical life, so it’s a bit annoying that we’re guinea pigs to that.”

You have some tour dates pencilled in for February. Are you optimistic about playing live again soon?

“I’m optimistic that the industry will get back onto its feet, but I really do hope that it’s not going to go back to normal. My touring schedule has been so intense that I honestly think I’ve gained five years of my life by not touring for a year. If there’s one thing I hope we’ll learn from this it’s that things can change at any moment.”

Have you seen anything change in the music industry that you’d like to stay permanent?

“The concept of touring for three years in a row is insane - it’s why all the musicians get depressed and become drug addicts. If more people spent time in the studio, better recordings would come out that have the potential to make as much money as mainstream music. Maybe having the luxury of spending six months in the studio would give artists like us a chance to compete and the definition of mainstream music would be broader. ”

So you intend to adapt your live strategy?

“I’d love to play smaller shows. When you play festivals the sound is so huge and the PA is so far away that you can’t even feel the music. If you’re wearing in-ears you might as well be in your studio with headphones! I’m a very physical performer and the interaction with the audience changes when I’m able to look people in the eye and react to them. I also think everyone has a better time when that happens.”

Ela Minus’s debut album Acts of Rebellion is out now on Domino Recordings.

Future Music is the number one magazine for today's producers. Packed with technique and technology we'll help you make great new music. All-access artist interviews, in-depth gear reviews, essential production tutorials and much more. Every marvellous monthly edition features reliable reviews of the latest and greatest hardware and software technology and techniques, unparalleled advice, in-depth interviews, sensational free samples and so much more to improve the experience and outcome of your music-making.

“He was like, ‘You’ve got it all wrong, man": Mumford & Sons reveal what Neil Young told them about the way they were approaching their live shows and album recordings

Dog Paw just invented a controller that looks like a drum pad but plays like it crossed a weighted piano with a violin…