"The speaker is on fire! This must be REALLY good": The incredible story of Eddie Van Halen’s Beat It solo

He created a legend but didn’t earn a dime. He destroyed the master tape (and a speaker). And they had to remake the track… backwards. No wonder Van Halen wasn’t their first choice…

The Beat It solo’s tortuous tale of how it was magicked into reality is only ever half told.

Van Halen wasn’t first choice for the gig, debate rages over what remuneration Van Halen received for his input, and how - preposterously - he would wind up fighting with himself for the number one spot.

There are speakers bursting into flames, an unexplained knocking sound and just who did buy those two packs of beer?

Here for the first time is the full twisting story of how the track was made, recorded and solo’d and then entirely re-recorded to make Eddie’s work the centre-piece miracle that still elicits joy and praise over 40 years later. But first, let’s turn back the clock.

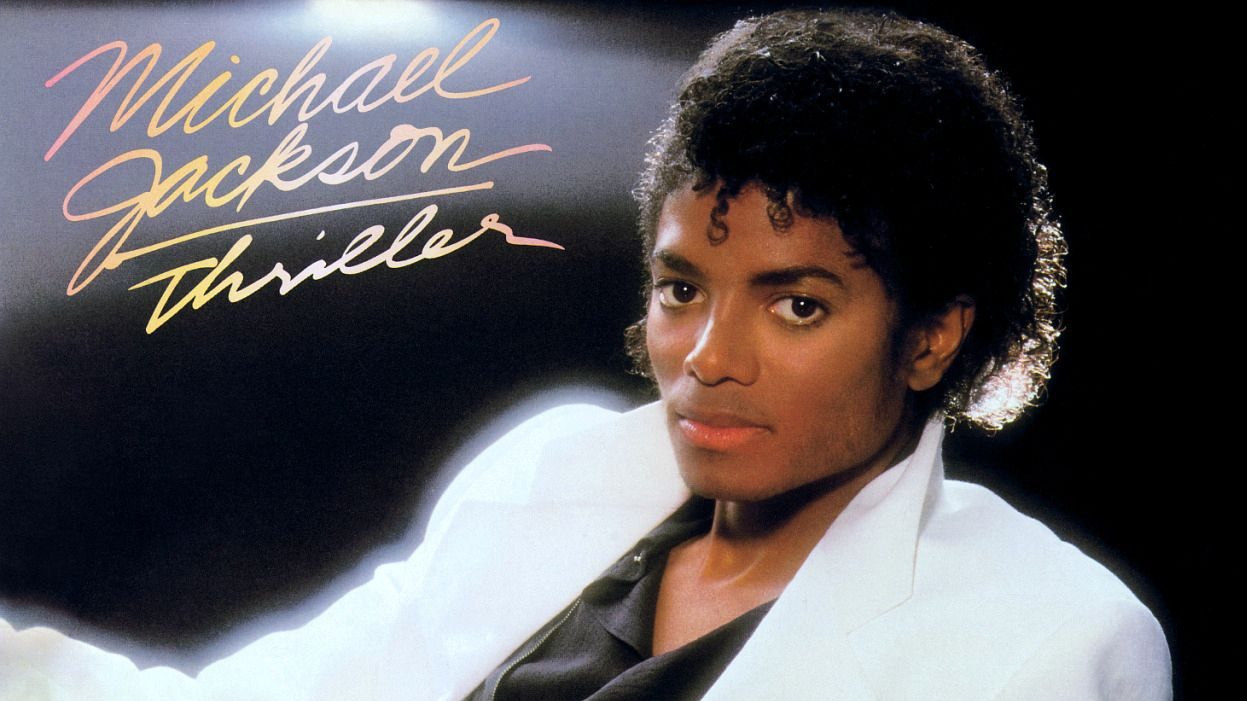

The year was 1982 and still hot from Off The Wall, Jackson and team – legendary producer Quincy Jones, super-engineer Bruce Swedien and Brit songwriting genius Rod Temperton – put the band back together for its sequel. An album that would go on to be the biggest-selling album of all time – Thriller.

But by 1982 the mood had switched away from the mellow grooves of Rock With You and wary of disco being a dirty word Jones was in a quandary as the new album took shape. While Wannabe Starting Something was funky and Thriller was exciting, what the album needed was something tough…

Michael was writing music like a machine. He could really crank it up.

Quincy Jones

In his autobiography Q, Jones says “Michael was writing music like a machine. He could really crank it up. In the time I worked with him he wrote three of the songs on Off the Wall, four on Thriller and six on Bad. At this point on Thriller I’d been bugging him for months to write a Michael Jackson version of My Sharona [the spikey new-wave hit by The Knack that had proved a hit on both sides of the Atlantic].

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“One day I went to his house and said, “Smelly [Jones’ affectionate nickname for Jackson], give it up. This train is leaving the station.” He said, “Quincy, I got this thing I want you to hear, but it’s not finished yet. I took him to the studio inside his house. He called his engineer and we stacked the vocals on then and there. Michael sang his heart out. The song was Beat It.”

"I wanted to write the type of song that I would buy if I were to buy a rock song," Jackson told Ebony in 1984. "That is how I approached it, and I wanted the children to really enjoy it – the school children as well as the college students."

Jones loved the new track and moving the sessions to Westlake Studios A and B on Santa Monica Boulevard West Hollywood, set about giving the demo the full treatment alongside trusted engineer Bruce Swedien.

It’s worth taking a moment to convey just how seriously Jones and Swedien took the recording process around this time. The pair worked in slick partnership, always eager to work with new equipment and, between them, armed with decades of tricks and techniques.

For example, Swedien had built his own custom drum riser and would insist that all drums were recorded upon it. “It’s 8’ square, 10” off the ground. It is very heavily constructed, braced and counter-braced. The surface is natural wood and is unpainted,” he explains in his autobiography Make Mine Music.

“The reason I wanted the drums to be up off the floor is to keep the low-frequency drum sounds, such as the bass drum and tom-toms, from coupling with the surface of the floor and entering the sound pick-up area of the microphones of the other instruments in the session.

"By putting the drum set up on my drum platform those low sounds never have a chance of connection with the floor and creating off-mic, obscure, secondhand pick up.”

Soon Swedien reasoned that if it sounded good for drums, why not record vocals on it too? Placing Jackson on the platform and surrounding him with studio Tube Traps, Swedien would painstakingly position them to create the perfect soundfield before capturing his vocals with vintage mics.

But he was no slouch on the latest tech too. At the time the hot new innovation in the best studios in the world was SMPTE. ‘Striping’ - as it was known - a track of tape with a digital code allowed two tape machines to lock together. Thus a 24-track tape machine, side by side with its ‘slave’, locked together, would effectively give you a 48-track machine. Well, 46 - minus two for the timecodes.

The SMPTE box would listen to the code on both tapes and run them in perfect lockstep. Rewind on one machine and hit play and the other would do the same. Magic.

Swedien used the technology to instigate his mysterious “Acusonic recording process”. He would record a performance on multiple synchronised tapes as he’d grown convinced that each time a tape was played it sounded a little worse. Soon he began the laborious process of putting one tape away as the master while continuing to work with the other. Upon mixdown he could swap back to the fresh, unplayed tape and spin it in as fresh as the moment it was recorded.

Thus Beat It was taking shape across two synced together 24-track tapes and was effectively in the can. But there was something missing. Eager to take his “rock track” experiment to the next level, Jones hatched an idea to further stamp it with authenticity.

Calling Mr Van Halen…

Quincy Jones had first worked with Toto guitarist Steve Lukather on his album The Dude after being introduced to him by songwriter and producer David Foster. Jones had found him an excellent creative foil, devising guitar parts on the spot and encouraging the guitarist to “do his thing” wherever guitar was needed.

He had already made use of his input on Thriller’s The Girl Is Mine featuring Paul McCartney, but it was Lukather’s friendship with Van Halen’s Eddie Van Halen that would prove more pivotal for Beat It.

Obtaining Lukather’s endorsement and Van Halen’s number, Jones made an out-of-the-blue call to the guitarist to request his services for a solo. But being called by Quincy Jones to play a solo on a Michael Jackson record? This is a wind-up, right? Van Halen hung up on his prank caller four times before wising up.

“I went off on him. I went, “What do you want, you f-ing so-and-so!” Van Halen explained to CNN in 2012. “And he goes, “Is this Eddie?” I said, “Yeah, what the hell do you want?” “This is Quincy.” I’m thinking to myself, “I don’t know anyone named Quincy.”

"He goes, “Quincy Jones, man.” I went, “Ohhh, sorry!” [laughs] “What can I do for you?” And he said, “How would you like to come down and play on Michael Jackson’s new record?” And I’m thinking to myself, “OK, ABC, 1, 2, 3 and me? How’s that going to work?”

"I still wasn’t 100% sure it was him. I said, “I’ll tell you what. I’ll meet you at your studio tomorrow.” And lo and behold, when I get there, there’s Quincy, there’s Michael Jackson and there’s engineers. They’re makin’ records!”

But what about the rest of the band that bears his name. What would they say about their star player batting for the other side? “I said to myself, ‘Who is going to know that I played on this kid’s record, right? Nobody’s going to find out.’ Wrong!” he laughs. “Big-time wrong.”

With Jackson’s vocals and basic guide percussion (Jackson banging on a drum case) on the master tape and the demo spanned out across the slave reel, there was bags of room on the master for Van Halen to work his magic. And mindful of the fact that Eddie liked it loud and his golden ears were far too valuable to risk, Swedien was eager to dip out of the session.

Speaking to Future Music magazine Bruce Swedien explains, “When Eddie came in to play, he was in Studio B at Westlake and I was in Studio A with Michael and Quincy, but I went in there when he was tuning and warming up and I left immediately. It was so loud, I would never subject my hearing to that kind of volume level!

"I didn't record that solo, I hired his engineer - I figured his hearing would probably be a little suspect right now anyway.”

Thus button-pushing duties fell to Van Halen’s regular engineer Don Landee who arrived with the maestro at Westlake studios for a quick briefing from Jones.

Van Halen explains: “I asked Quincy, “What do you want me to do?” And he goes, “Whatever you want to do.” And I go, “Be careful when you say that. If you know anything about me, be careful when you say, “Do anything you want!” And with that the pair were left to their own devices, but upon listening to the track Van Halen was less than impressed.

Perhaps naive as to the landscape of rock, the 16-bars of backing Jones and Jackson had laid out for Van Halen to explore were the repetitive chugging, one-note chant that still exists on the finished track from 2:21 to 2:49. While Jones and Jackson saw it as a rhythmically diverse and thrilling playground, for Van Halen it was a 16-bar wasteland with zero musical peaks or valleys for the ambitious soloist to traverse.

Feeling hemmed in by the scant musical progression on offer, Van Halen suggested that it’d be far better for him to solo over the song’s verse instead and that the song be rearranged so that his solo could “have some place to go”.

As chins were being rubbed in Studio B, Jones and Swedien and Jackson had other fish to fry, along the corridor in Studio A. There was the small matter of knocking out an E.T album for Steven Spielberg…

Yes, even as far back as 1982 entertainment corporations were sufficiently savvy to plunder every possible merchandising avenue, and with all the signs that Spielberg’s upcoming family-baiting, sci-fi weepy, ET: The Extra Terrestrial, was going to be a smash, they needed product on shelves to mop up the hysteria. With the home video market in its infancy, the team reasoned that if punters couldn’t watch the movie at home, then at least they could listen to it.

Thus a deal had been struck between Universal Pictures, MCA Records, Quincy Jones and Michael Jackson to make a soundtrack album and storybook featuring John Williams’ movie score alongside Jackson narrating a cut-down storyline and new songs and music by regular Jackson collaborator Rod Temperton.

Jones and Jackson reasoned that with Williams’ music in the can, the studio booked and the talent already assembled, how hard could it be to cut two albums at once?

Thus - bizarrely - Thriller (and Beat It) were completed side-by-side with E.T’s soundtrack sharing the same studio and production team.

Cutting the tape

Back in Studio B, and with Jones and Swedien’s backs turned, Van Halen and Landee had found a solution. If Landee edited in a copy of the verse, lengthening the song and ending his solo with a chorus Van Halen would have his dream 16-bar playground.

Thus Landee took a razor blade to the two-inch 24-track master tape of an unreleased Michael Jackson song, making a gutsy call in order to deliver the canvas his boss required.

I warned him [Jackson] before he listened. I said, “Look, I changed the middle section of your song…”

Eddie Van Halen

Firing up a modified Hartley Thompson amp that Van Halen had borrowed from guitarist Allan Holdsworth (an HT45 combo and HT45S cab), his favourite Echoplex tape delay and, of course, his Frankenstrat, two takes later the deed was done and lightning was captured in the bottle. But what would the fastidious Thriller team - not least Jackson himself - think of Van Halen and Landee’s hasty rework?

Speaking to CNN Van Halen says, “I was just finishing the second solo when Michael walked in. And you know artists are kind of crazy people. We’re all a little bit strange. I didn’t know how he would react to what I was doing. So I warned him before he listened. I said, “Look, I changed the middle section of your song…”

“Now in my mind, he’s either going to have his bodyguards kick me out for butchering his song, or he’s going to like it. And so he gave it a listen, and he turned to me and went, “Wow, thank you so much for having the passion to not just come in and blaze a solo, but to actually care about the song, and make it better." He was this musical genius with this childlike innocence. He was such a professional, and such a sweetheart.”

With the musical transaction complete within half an hour and Jackson’s seal of approval, there was just the small matter of extinguishing a flaming monitor…

The story goes that during the recording of Van Halen’s solo his playing was so “hot” that a speaker in the control room burst into flames. "The speaker is on fire! This must be REALLY good,” exclaims Rod Temperton on Van Halen’s solo in a BBC documentary about the making of the album.

On Beat It the level was literally so hot that at one point in the studio, Bruce Sweden called us over and the right speaker burst into flames

Quincy Jones

However, given that Temperton wasn’t present it’s Jones' version of events that are probably more likely. Yes, during the mixing process for the album a speaker did catch fire, but Van Halen’s solo wasn’t to blame. “We knew the music was hot. On Beat It the level was literally so hot that at one point in the studio, Bruce Sweden called us over and the right speaker burst into flames,” says Jones in Q. “We’d never seen anything like that in forty years in the business.”

But while spontaneously combusting monitor rumours can be extinguished, Van Halen DID leave the team with an even bigger problem. Beat It spanned two 24-track tapes, a master and a slave, locked with that SMPTE stripe.

But by cutting one of the tapes, inserting a new section and gifting Van Halen his playground, Landee had committed the cardinal sin of SMPTE and inadvertently destroyed the continuity of the code. Now the two halves of Beat It wouldn’t play together… So while Jackson’s vocals and Van Halen’s solo were safe and sound together on one tape, the second, containing the in-progress backing track was cut adrift.

Returning to Westlake the next day Jones and Swedien realised that they had a dilemma. Their perfect Jackson vocal and blazing Van Halen solo were now trapped on a tape separated from the rest of the track. And as for bouncing them down or transferring to the other tape? Don’t be ridiculous. There was only one thing for it.

Jones made a call to Steve Lukather. “You gotta make the track backwards to what you can hear on the tape. I don’t want to do Michael’s vocals again. I want to keep it first generation. I’ve got Eddie’s solo and you’ve gotta make it work,” explained Jones…

Rebuilding Beat It

With Westlake maxed out with the Thriller-plus-E.T. double-header, Lukather was instead dispatched to Sunset Sound with the Jackson-plus-Van Halen master tape along with fellow Toto luminary, drummer Jeff Porcaro and engineer Humberto Gatica.

The tape featured just three sounds: Jackson’s multi-tracked, multi-layered lead and backing vocals, Van Halen’s blistering solo and the sound of Michael Jackson beating on a drum case marking time on beats two and four - a sound which, if you listen carefully, is there in the final mix.

Toto’s guitarist and drummer would have to recreate everything else on a track they’d not heard in full (or so far had any part in) from scratch…

Where to start? Listening closely, Porcaro tuned into the bleed from Jackson’s headphones and taking a pair of sticks was able to play along with the distant backing track, tapping the sticks together to create his own human click track. Once committed to a new tape synced with the master he was then able to play along, nailing Beat It’s drum track in just two takes.

With Beat It’s beat in place and taking inspiration from Van Halen’s scorching solo, Lukather fired up a quad-speakered Marshall cab and amp and gave it both barrels for his rhythm guitar parts. And, although by no means a bassist, Beat It’s basic bass meant that Lukather was able to nail that too. Thus, after a few hours the pair had ostensibly turned back time and rebuilt the track bigger and better than ever before.

Time to get Q’s verdict… And he wasn’t happy.

While he admired the duo’s game-saving performance, when slung alongside Van Halen’s solo it was all getting a little too heavy. "Q said, 'We love it but Lukey it's too much, I've got to get this on pop and r’n’b radio and it's just too metal,” explains Lukather to Rick Beato. “You've got to come back down. Get that little Fender of yours out, don't turn it all the way up. Give it the gas… but don’t…” Understanding Jones’ vague diktat, Lukather reached for his old Paul Rivera-modded Fender ‘68 Deluxe black face and instead recorded a sound that’s solid rock but easy on the metal.

They had the same riff going for something like 45 bars but I was like, "Nah, try this, it makes it more interesting..."

Steve Lukather

And just as Van Halen had nixed the idea of his boring solo spot, so Lukather found Beat It’s original two-chord guitar part more than a little lacking.

The original verse was a relentless thrash with Jackson’s writing at the time still in its infancy. Wanna Be Starting Something, for example, is similarly just two chords, C and D and inspired by Jones to create something like the naggingly repetitive My Sharona, Jackson done just that. Assuming that the repetition was the song's strength Jackson had kept it simple. Now Lukather wanted to amp it up.

“They had the same riff going for something like 45 bars but I was like, 'Nah, try this, it makes it more interesting',” says Lukather of his variation that you hear at bar five and thirteen in the verse. “I had to sell them on it but they finally went for it.” Add synths from fellow Toto bandmate David Paich and Lukather and team had officially saved the day. But wait a second… What’s that sound?

Who’s a-knocking?

There’s still debate as to the origins of the strange knocking sound that can be heard at 2:44, immediately before Van Halen’s solo flight.

One theory is that it’s Van Halen himself, knocking to get into the recording booth, eager to begin his solo. Another is that it’s an impromptu percussion performance by Jackson. Thriller’s sleeve notes give a credit to Jackson as “Drum Case Beater” which would solve the mystery, but, as we observed earlier, this is referring to the two and four beat extra ‘thwack’ Jackson performed alongside his vocal.

The sound is therefore most likely Van Halen dragging his plectrum a few clicks down the bottom E string or simply his guitar strap or tremolo arm flexing and creaking as he makes himself comfortable.

It’s remarkable that the sound is there at all. The super-fastidious Swedien – a man who would religiously isolate and fix every kick pedal squeak or mic stand thud – would have normally nuked it but it’s clear that Jones and Jackson wanted it left on board as part of the performance.

“Even when we do backgrounds. Michael does little vocal sounds and snaps his fingers and taps his foot,” says Swedien in Make Mine Music. “I keep those sounds as part of the recording. I absolutely love those little sounds as part of Michael’s sonic character,” Obviously the team felt likewise about Van Halen’s pre-performance creaking.

The sound at 2:44 proves to be the perfect precursor for the carnage to follow. It’s easy to picture Van Halen firing up a chainsaw before delivering his devastation. With it Beat It’s solo doesn’t so much ‘begin’ as get pistol-whipped awake, revved up and then uncaged.

Money’s too tight…

Needless to say upon the track’s release on Valentine’s Day, February 14th 1983 the song proved a huge smash, coming off the back of Billie Jean it cemented the album’s reputation, making good on Jackson’s Thriller aim that “every track would be a killer.” The track went on to become a five-times platinum number one single, selling seven million copies worldwide.

One take on Beat It’s financial aftermath would be that Van Halen was done up like a kipper

All of which must have meant quite the payday for Van Halen’s 20 seconds of work (31 including knocking and divebomb to finish)… But by now you’ve probably deduced that this story can’t end like that.

One take on Beat It’s financial aftermath would be that Van Halen was done up like a kipper. As a friend of Lukather (and summoned by none other than Quincy Jones) Van Halen simply turned up and did his thing as a favour with no talk of payment for his time and effort. He reworked the song, conjured up one of the most amazing guitar solos ever and helped bring Jackson’s music to a whole new league of fans… And got zilch.

Van Halen debates this take on events. “I was a complete fool, according to the rest of the band, our manager and everyone else,” Van Halen says. “I was not used. I knew what I was doing – I don’t do something unless I want to do it.” And writing in Edward Van Halen: A Definitive Biography, author Kevin Dodds quotes Eddie’s wife at the time Valerie Bertinelli confirming that “Ed never saw a dime, nor do I believe that he ever thought to ask to get paid. That was Ed.”

Jones has stated that he provided beer at the session by way of thanks but even this scant offering is upturned by Van Halen himself. “Actually, I brought my own, if I remember right,” said Van Halen to CNN, which would mean that he literally got nothing for transforming the track.

"Certain people in the band at the time didn't like me doing things outside the group," the Van Halen News Desk reported Eddie as saying. "But Roth happened to be in the Amazon or somewhere, and Mike [Anthony] was at Disneyland and Al [Van Halen] was up in Canada or something. So I thought, well, they'll never know."

But - of course - given Van Halen’s unique style they would find out sooner or later. “I was in a parking lot on Santa Monica near Sweetzer, the 7-Eleven, and there were a couple of butch Mexican gals with the doors open on their pickup truck and the new Michael Jackson song Beat It came on,” says Roth in Kevin Dodds’ book. “I heard the guitar solo and thought, now that sounds familiar… Somebody’s ripping off Ed Van Halen’s guitar licks. It was Ed, it turned out and he had gone and done the project without discussing it with anybody.”

The rest of the band were furious. They’d all pledged that any external projects would have to be mutually agreed by the rest of the band and now here’s Eddie getting all the Van Halen limelight (for none of the cash). And things were about to get worse in the eyes of his bandmates…

Van Halen’s album 1984 had been ascending the charts with a genuine shot at number one. Writing in his book Speed of Sound, Thomas Dolby came face to face with the band's dissatisfaction with Van Halen’s generous nature.

Visiting Van Halen’s mock Tudor Mullholland mansion to record his contribution for Dolby’s Easter Bloc album track and Close But No Cigar single he got the cold shoulder from Alex Van Halen.

“He looked at me suspiciously,” says Dolby. “‘I hear you’re not nuts about Eddie playing on my album?’ I inquired. “You got that right bro,” said Alex. “Last time we let him do that he did a solo on that little fucker Michael Jackson’s record. That was the only reason 1984 got stuck at number two.”

And thus the story is complete and history is made… But it could have been so different. Speaking to Rolling Stone in 2020 after Van Halen’s death, The Who’s Pete Townshend insists it was he who got the call first.

“I was once asked by Michael Jackson to play electric guitar on the Thriller album,” Townshend said. “I said I couldn’t do it but recommended Eddie who called and we chatted.

"He was utterly charming, happy about the connection, but told me how much he was enjoying playing keyboards. His smile was just classic. A man in his rightful place, so happy to be doing what he did.”

Daniel Griffiths is a veteran journalist who has worked on some of the biggest entertainment, tech and home brands in the world. He's interviewed countless big names, and covered countless new releases in the fields of music, videogames, movies, tech, gadgets, home improvement, self build, interiors and garden design. He’s the ex-Editor of Future Music and ex-Group Editor-in-Chief of Electronic Musician, Guitarist, Guitar World, Computer Music and more. He renovates property and writes for MusicRadar.com.

“It is ingrained with my artwork, an art piece that I had done years ago called Sunburst”: Serj Tankian and the Gibson Custom Shop team up for limited edition signature Foundations Les Paul Modern

“The last thing Billy and I wanted to do was retread and say, ‘Hey, let’s do another Rebel Yell.’ We’ve already done that”: Guitar hero Steve Stevens lifts the lid on the new Billy Idol album