Early DAWs: the software that changed music production forever

Join us for a history lesson, as we uncover the ancestry of Cubase, Logic, Ableton Live and more

Digital audio workstations - or DAWs - are now the mainstay of most producers’ workflow, but despite their cutting-edge credentials, you might be surprised at just how far back their roots can be traced. In the early 1980s, the first, primitive versions of what we now call digital audio workstations began changing the way musicians could express themselves.

The best DAWs 2020: the best music production software for PC and Mac

The musical landscape looked very different back then, with computers just starting to become a viable option for making music, and the introduction of MIDI was a revolution when it came to controlling synths, drum machines and samplers. The idea of recording or editing digital audio on a computer was still a long way off, but even the earliest music programs offered new options that had never existed before.

Why does this matter? To many of today’s musicians, what happened more than three decades ago might seem irrelevant to the way we make music today. We wouldn’t go so far as to insist you must learn your history to understand how good we have it today, but it really puts into perspective just how far we’ve come in such a short space of time. Asking a few basic questions can help us understand the incredible music-making power we have at our disposal in software today. What was a sequencer, and how did that evolve into a DAW? How important was MIDI? What about trackers, chiptune and the demoscene? How did newer DAWs change the game? What about the computer platforms and programs that didn’t make it?

Join us, then, as we take a nostalgic look back at the origins of some of the most popular DAWs and tell the story of how computer music was born.

As Bob Marley put it: “In this bright future, you can’t forget your past.”

The godfather of DAWs: Steinberg Cubase

How far back can we trace the story of modern DAWs? At least as far as 1983, when keyboard player Manfred Rürup met engineer Karl ‘Charlie’ Steinberg and conceived the idea of a software MIDI sequencer. They were truly ahead of the game: the MIDI specification had only been formally announced the same year.

The duo founded Steinberg Research and developed their first program, Multitrack Recorder, a 16-track sequencer for the Commodore 64. Despite selling fewer than 50 copies, the program laid the foundation for a dynasty that continues to this day. Multitrack Recorder became Pro-16, then Pro-24, Cubit and eventually Cubase. Commodore 64 development shifted to the Atari 520ST, then the Commodore Amiga, then eventually the Apple Mac and Windows PC.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

So, what exactly did it do? Frankly, not a lot. By modern standards, early Cubase was hilariously basic. Until the early 90s, the software did little more than control external MIDI devices via a suitable interface. Updates focused on very basic usability functions like editing and rearranging MIDI phrases, mixing MIDI signals and sending SysEx messages.

Audio functionality followed for the fast new Power Macs in 1993, using hardware developed by Digidesign for their new Pro Tools system. Plugin support arrived in 1996, establishing the basic template we now think of as the modern DAW: MIDI sequencing, audio recording, audio effects and (eventually, with the implementation of VSTi in 1999) virtual instruments. Cubase development continues to this day, with v10 released last November and the program celebrating its 30th birthday this year.

Cubase is arguably the main player in the story of computer music as we know it. The modern DAW might have evolved in some way without the intervention of Rürup and Steinberg, but there’s no doubt they were instrumental in defining the state of 21st century music technology.

Highly logical: Emagic Logic

The story of Cubase runs parallel with that of its main rival, Logic. Both trace their roots to the '80s, both originated from small developers in Germany, and both are still made today.

Like Cubase, Logic evolved from a simple mid-80s C64 MIDI sequencer, C-Lab Softtrack 16+, released in 1985. It went through a few iterations before it became what we now know as Logic, with Softtrack first spawning C-Lab Creator and Notator for the Atari ST, before lead developers Gerhard Lengeling and Chris Adam left to form Emagic and release Notator Logic in 1993, eventually renamed Logic.

Despite their similarities, there were also big differences between the proto-versions of Logic and Cubase along the way. Whereas Cubase was initially quite linear and track-based, Creator and Notator took a more pattern-based approach, allowing users to string together blocks of MIDI data to create song arrangements. The approaches aligned after the release of Notator Logic, and as both Cubase and Logic matured with the addition of similar audio functionality, plugin effects and virtual instrument capabilities.

Anyone who started making music after 2002 will know that Logic is only available for Mac OS, but this wasn’t always the case. Early versions of Notator Logic were on the ST platform but shifted over to Mac and Windows as the Atari gradually became obsolete.

On July 1 2002, Apple announced their acquisition of Logic’s parent company Emagic, lock, stock and barrel. Lengeling and team moved to California to oversee the Logic project (and related work). Apple’s software is only ever available for Mac OS, so Windows development shut down immediately and Logic for Windows died with version 5. This is the crucial moment in the Logic story, defining Apple’s interest in DAWs and shifting development exclusively to Mac OS.

What’s notable about Logic is its price, relative to equivalent DAWs. Logic Pro X retails at £199.99. Compared to Cubase Pro 10 at £480 and Ableton Live Suite at £539, you can see how much Apple subsidise their software. So, not only is Logic a highly developed package, but it’s a bargain for Mac users. From humble C64 roots, it’s now one of the modern DAW giants.

From live looping to studio staple: Ableton Live

Necessity is the mother of invention, and that’s certainly long been the case in music. Whether it’s guitar players developing electric pickups and amplifiers to compete with the increasing volumes of big bands, or Kraftwerk developing their own drum machines and synths, countless technological innovations have been created by frustrated musicians. The same can be said of Ableton Live, initially developed by Bernd Roggendorf with Gerhard Behles and Robert Henke, also known as techno duo Monolake.

Behles and Henke had previously designed a step sequencer, PX18, for their own use. Coded using Cycling 74’s Max visual programming language around 1995, PX18 was in some ways a prototype version – or at least a forerunner – of Live, with a vaguely familiar user interface. You can still find it on the Cycling 74 website, in fact.

Within a couple of years, the Monolake chaps had moved on to develop a different piece of software with a focus on sample playback. Early versions of Live were basic affairs by modern standards, but still a big step up from the simplicity of PX18, and clearly following their own path, with the focus very much on looping and triggering samples, timestretching and live manipulation of sequences and sets.

High performer

Live is an adolescent DAW compared to Logic, Cubase and co, the company being founded in 1999 and its first commercial release only arriving in 2001. As the name implies, its roots are in live performance as opposed to the studio sequencing and recording tasks that dictated the development processes of most other DAWs. The original motivation for developing the software stemmed from a frustration at the limitations of existing tools for performing with samples. Live’s entire clip-based workflow is derived from that initial raison d’etre, offering what was, at the time, a completely new approach to live performance. It’s still one of the most versatile, and effective ways to perform electronic music live.

Non-linear thinking

We now think of Live as a fully-fledged DAW in its own right, but a lot of its key features arrived much later than you may realise. MIDI sequencing and virtual instrument support weren’t even added until version 4, which shows just how laser-focused the first few versions were on the idea of warping, triggering and arranging samples and loops.

If Live didn’t completely tear up the rules on how a DAW should work, it turned a blind eye to many existing conventions. The software’s real-time warping and sound processing options are extensive, but the Session View grid is possibly Live’s greatest contribution to music making. It’s a completely different approach to most DAWs, breaking away from the linear sequencing format and changing the way we think of arranging music (the complementary Arrangement View is closer to the traditional linear timeline used by most DAWs).

If you see an electronic act perform live these days, there’s a very good chance that Ableton Live will be employed somewhere in their setup. But even more importantly, Live has become a studio mainstay for electronic producers and anyone who feels restrained by the strict linear timeline of so many other DAWs. Many users find it to be the most intuitive, user-friendly way to approach making loop-based electronic music, which is unsurprising considering its techno roots.

Back in the garage: how Logic spawned GarageBand

Apple’s entry-level DAW is much younger than its big brother, but GarageBand shares more DNA with Logic than you might realise. When Apple acquired Emagic in 2002, the company’s co-founder, Gerhard Lengeling, moved to California to take on a new role as senior director of software engineering (music applications).

Apple play their cards very close to their chest when it comes to software development, but it’s widely believed that a big part of their reason for buying Emagic was to leverage the technology behind the Logic software itself, plus the expertise of Lengeling. Within a couple of years, Lengeling and his team had developed Logic 6, but also another entirely new DAW.

Announced by Steve Jobs in his keynote speech at the 2004 Macworld Expo, GarageBand was notable for the fact it was immediately bundled free with every Mac, meaning that all Mac users have a decent user-friendly DAW to play with. But don’t assume that GarageBand is only an entry-level toy; under that friendly surface, it’s powerful, and since its release it’s been used to demo or even record countless commercial releases (see Rihanna’s giant 2007 hit Umbrella, based on GarageBand’s ‘Vintage Funk Kit 03’ drum loop).

It’s also notable that GarageBand is Apple’s choice for the iOS platform. You can’t run Logic on your iPad or iPhone, but the mobile version of GarageBand is a surprisingly capable piece of software, with the ability to export projects to the desktop version. GarageBand marked a major shift in the landscape of music software, democratising and opening up the possibilities to a bigger audience than ever before.

Storm in a teacup

Of all the DAWs we lost along the way, the strangest of them might have been Arturia’s Storm. Released in early 2000, Storm was kind of a DAW but also kind of not. In the end, that was probably its undoing.

Described by Arturia as a virtual studio, Storm combined sequencing, instruments and effects in a combined package, with Roland-inspired drum machines, acoustic samples, various vintage synth modules and loop players.

The first version focused heavily on combining pre-made loops and sequences to create tracks, but Storm evolved (slightly) into something capable of creating original tracks from scratch. Storm was best used when Rewired to another DAW, but if you’re going to all that trouble, why not simply use a better DAW in the first place? Its closest rivals were other young, fresh DAWs like FruityLoops (now FL Studio) and Propellerhead Reason; unfortunately for Arturia, they both just did things better.

Storm made it as far as 2004’s version 3 before Arturia finally cut their losses and pulled the plug to focus on virtual instruments. Storm remains a curiosity rather than a long-lost classic. Its best features made it into other Arturia plugins. Plugins you can use in a proper DAW.

The dawn of plugins

One basic requirement of a modern DAW is that it should act as a plugin host. Any half-decent DAW is expected to include a range of built-in virtual instruments and effects, and let you call up plugins from third-party developers. However, most sequencers and DAWs didn’t have plugins, virtual instruments or even audio effects until well into their evolution.

The potential of digital signal processing (DSP) emerged during the 1960s, as computer technology allowed telecommunications companies and scientific researchers to start experimenting with audio signals. New York effect specialists Eventide were the first to bring this radically new technology to the studio with the release of their primitive DDL 1745 digital delay line, but it was their Harmonizer H910 multieffects unit, released in 1975, that really established digital technology as the future of studio processing. Over the next decade, digital effects became more common and affordable, while mass-market digital synths and drum machines also eventually emerged from the early 80s onwards (a few options such as the Synclavier and Fairlight existed in the 70s, but these were hugely expensive).

Despite the rise of digital audio hardware, the idea that this kind of DSP could take place natively within a music sequencing application running on a personal computer was unrealistic at best; early sequencers offered no audio capabilities whatsoever, while early version of Pro Tools relied on dedicated DSP hardware for their audio functionality. As hard as it might seem to understand from a 21st-century perspective, the ability to sequence and synchronise external instruments via MIDI was enough of a revolutionary idea in its own right. Digital audio processing in software followed eventually, but it took a couple of decades to mature and become ubiquitous.

VST’s arrival

As far back as 1982, Eventide were the first to use the word ‘plugin’ in an audio context, although in their case it referred to physical EPROM chips that could literally be plugged into the SP2016 effects unit, allowing the user to add new programs to the hardware. The widespread proliferation of plugins as we now know them only really became viable once computer processing power caught up with the potential of digital signal processing in the mid 1990s.

The real turning point came in 1996, with the introduction of the standardised VST (Virtual Studio Technology) plugin spec for effects. Steinberg released the format to the world alongside Cubase 3 as a cross-platform standard, encouraging others to follow suit and establish an industry standard. Three years later, the VSTi virtual instrument specification was added. 13 years on from its initial release, VST and VSTi are still going strong, updated accordingly and flanked by Audio Units for Mac and the AAX format for Pro Tools. The last major DAW to hold out against third-party plugins was Propellerhead Reason, which only succumbed to VST support in 2017. “VST support in Reason? When hell freezes over,” joked Propellerhead’s then-CEO Ernst Nathorst-Böös as he announced its arrival.

Whatever your DAW, you can now take your pick from thousands of plugins, ranging from simple freeware to big-budget virtual instruments and pro-grade effects.

Sequencers vs DAWs

A lot of musical terms have been abused, misused and otherwise mangled over the years. If you want proof, just try explaining to a guitarist that the vibrato effect on their amp is actually tremolo, and that wobbling the tremolo arm on their guitar actually creates vibrato. Confused? We don’t blame you…

Strictly speaking, the difference between a sequencer and a DAW is simple. The clues are in the names: a sequencer sequences or controls instruments using MIDI data or other control protocols, while a DAW handles digital audio.

In this case, though, we can forgive the fact that the two terms are sometimes used interchangeably, given that so many modern DAWs started life as sequencers. Some of the biggest DAWs on the market – notably Logic and Cubase – began as sequencers years before audio functionality was added. Others, like Pro Tools and Ableton Live, were always DAWs, but to some extent their ability to sequence instruments (virtual or hardware) is also pretty inherent to the concept.

Strictly speaking, they’re all DAWs with sequencing capabilities, but if you refer to Logic or Live as a sequencer, people will probably still know what you mean. Now, what was the difference between vibrato and tremolo again?

Crackers and trackers

The 1980s were a strange period in music history. The music of the '60s and '70s suddenly seemed incredibly dated as synths, drum machines and samplers began to take over. Music videos emerged as a fresh, bold vision of artistic expression, while musicians began experimenting with sounds that had never been heard before.

The biggest problem was that for much of the '80s, computer technology couldn’t keep up with the promise of a brave new future. Computers were just about starting to establish themselves as an option for sequencing and recording, but for some, it wasn’t enough. One side of the story is self-explanatory and written into history as the simple process we’ve described elsewhere: sequencers let people program hardware, DAWs eventually evolved into what we now know as music software.

But there’s another story that runs in parallel, lurking in the shadows away from the mainstream. Rather than professional studios and slick music videos, it revolves around early video games and the so-called ‘demoscene’, a subculture based on showing off programming skills via music and graphics, often going hand in hand with software cracking and piracy. Whether legit or not, programmers exploited the basic musical power of the Commodore 64 and the Amiga to showcase their talents, using incredibly clunky software such as Superions Future Composer and SIDMON.

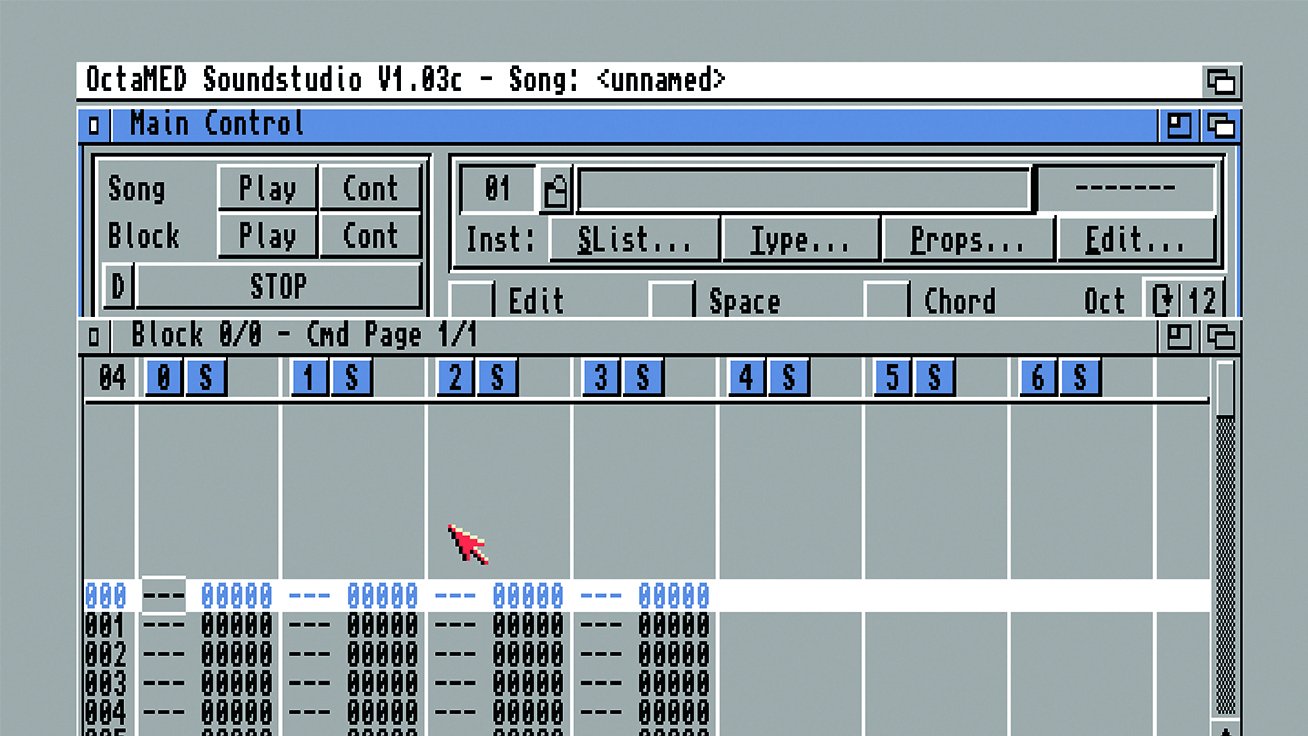

Following the release of the (marginally) more intuitive Ultimate Soundtracker for Amiga, the whole software category became known as trackers, and the tracker scene evolved separately to the more user-friendly sequencer market. Typically based around numerical data entry and vertically scrolling timelines, trackers seem alien to most modern DAW users, but they’ve remained popular among a relatively small, hardcore group of users, with programs like OpenMPT and Renoise still available.

There’s a crossover with the even more hardcore chiptune scene, in which producers push the limits of the sound chips of arcade games and consoles. Both have been responsible for big hits: Calvin Harris’s first album was reportedly made entirely on OctaMED for the Amiga 500, while Timbaland settled out of court with Finnish demoscener Janne Suni after his production on Nelly Furtado’s Do It was found to be notably similar to Suni’s chiptune track Acidjazzed Evening.

What the tracker, demo and chiptune scenes might lack in size they make up for in moxie.

Acceptable in the '80s: Amiga and Atari

Life is pretty simple now. If you want a new computer, you probably ask your mates whether to go for a Mac or a Windows PC. For the small minority who want something leftfield and techy, Linux might be a contender.

In the 80s, however, things were different. Depending on your budget and what you intended to do with your cutting-edge personal computer, you could take your pick from Sinclair Spectrums, Apples, BBC Micros, IBM PCs, Acorns, Amstrads, Commodore 64s…

Most crucially, almost none of these platforms were compatible with one another. Hardware and software were extremely restrictive by modern standards, and in many cases, users were expected to demonstrate a basic understanding of programming and command-line operating systems just to carry out the most basic tasks.

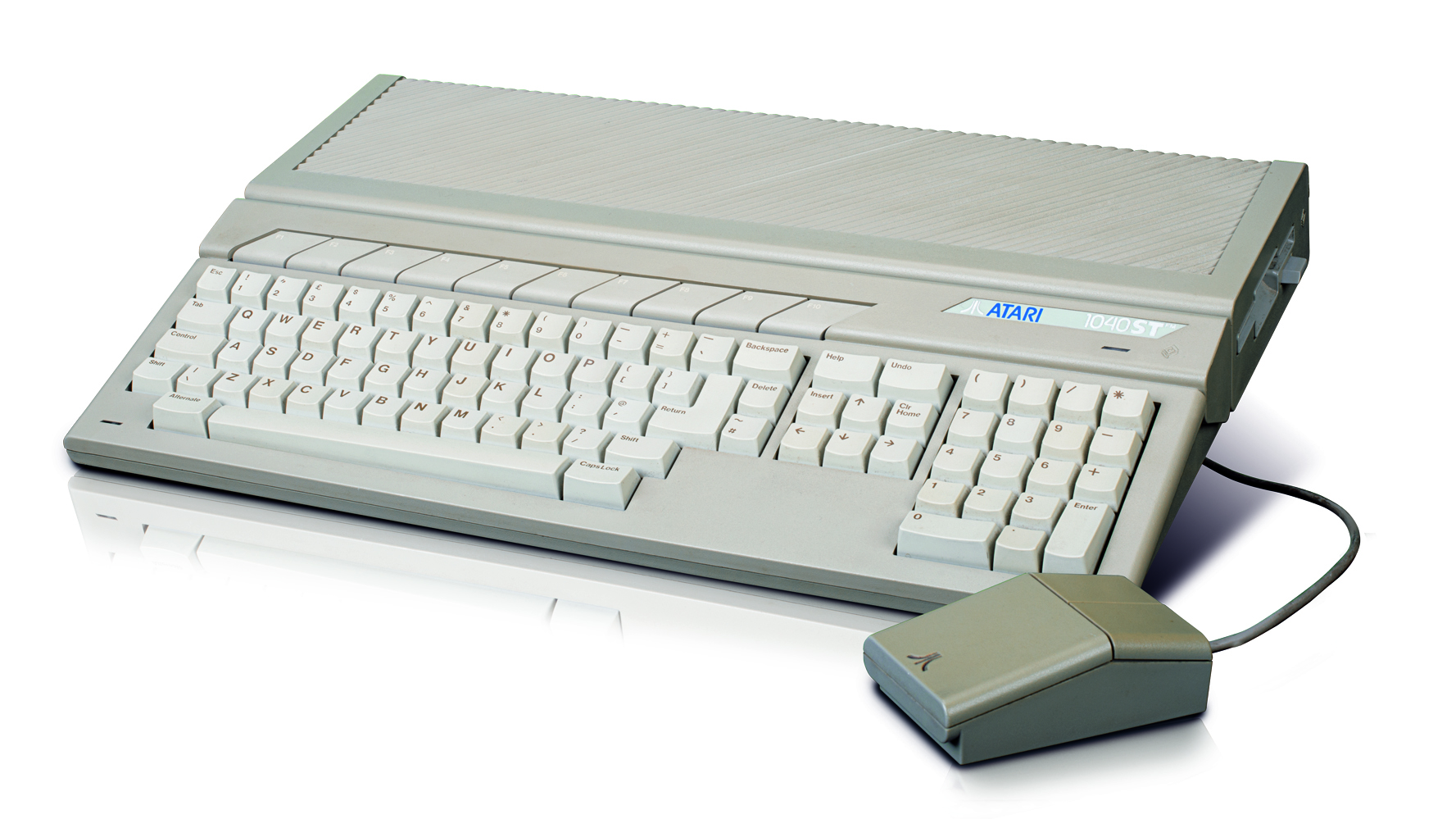

With the shift from 8-bit to 16-bit computing, the pack was whittled down to a few key players. Notably for musicians, 1985 saw Commodore release the Amiga range, while Atari announced the ST. The two were fairly evenly matched in terms of processing power, but the Atari had one key advantage: a built-in MIDI interface, with 5-pin DIN input and output. Hook up a synth or a drum machine and you immediately had the makings of a basic home studio setup.

Unfortunately, the Amiga and Atari wouldn’t ultimately survive for long. The eventual demise of both platforms had less to do with the capabilities of the machines than changing trends in the personal computer market.

Atari never fully recovered from the video game crash that took place in 1983, during which the console market became flooded and dominated by new players including Nintendo and Sega.

Commodore likewise failed to establish the Amiga as a serious business or professional option against the Macintosh and Windows alternatives, establishing a decent foothold in the formative digital graphics and multimedia industries before eventually filing for bankruptcy in 1994, clearing the way for Apple and Microsoft to dominate.

The importance of MIDI

Talk to anyone who tried to make music with synths and drum machines before MIDI and you’ll hear tales of the horrors they endured.

Before MIDI, trying to control multiple pieces of hardware was, to put it politely, a pain in the neck. Synchronisation of clock signals was just about manageable, but sending CV (control voltage) signals to trigger notes was a different matter.

If you wanted to tune multiple pieces of kit or attempt anything polyphonic, things got even more tricky. It was more or less possible, sure, but you certainly needed more patience than most people could manage in a lifetime.

As for sequencers, they were basic. Monophonic analogue synths worked best with simple step sequencers, repeating the same basic 16th-note pattern over and over indefinitely. More advanced options existed, but would you really want them and could you even afford them? Roland’s MC-8 Microcomposer, released in 1977, cost $4,795 – a little over $20k in today’s money. It was reported to be hard to program and took the best part of an hour to back up a 3-4 minute sequence. Fewer than 200 units were sold.

The MIDI standard was released to the world in 1983 as a way for manufacturers to standardise the way their synths, sequencers and drum machines communicated with each other. (A quick reminder for those who haven’t been paying attention for the last 36 years: MIDI is essentially a control protocol, allowing pieces of musical equipment to communicate with each other. There’s no audio sent down MIDI cables, just simple instructions: play this note now; change that parameter; trigger this program change…)

Why is all of this relevant to DAWs? Because you can think of MIDI as the glue that held early sequencers together, allowing them to control other studio equipment. The same applies to modern DAWs: the nuts and bolts may be hidden in the background for the most part, but control signals based on the concept of MIDI remain the foundation of most 21st century music software.

Hardware sequencers still exist to this day in the form of gear like the Sequentix Cirklon or newly announced Pioneer Toraiz SQUID, but software has very quickly taken over as the easiest, most intuitive solution. In a curious twist of fate, MIDI has become relevant once again as trends have shifted back from 100% in-the-box software setups toward hybrids of software and hardware, but chances are you’re going to want to control everything from your DAW. And you can. We have MIDI to thank for that.

Computer Music magazine is the world’s best selling publication dedicated solely to making great music with your Mac or PC computer. Each issue it brings its lucky readers the best in cutting-edge tutorials, need-to-know, expert software reviews and even all the tools you actually need to make great music today, courtesy of our legendary CM Plugin Suite.