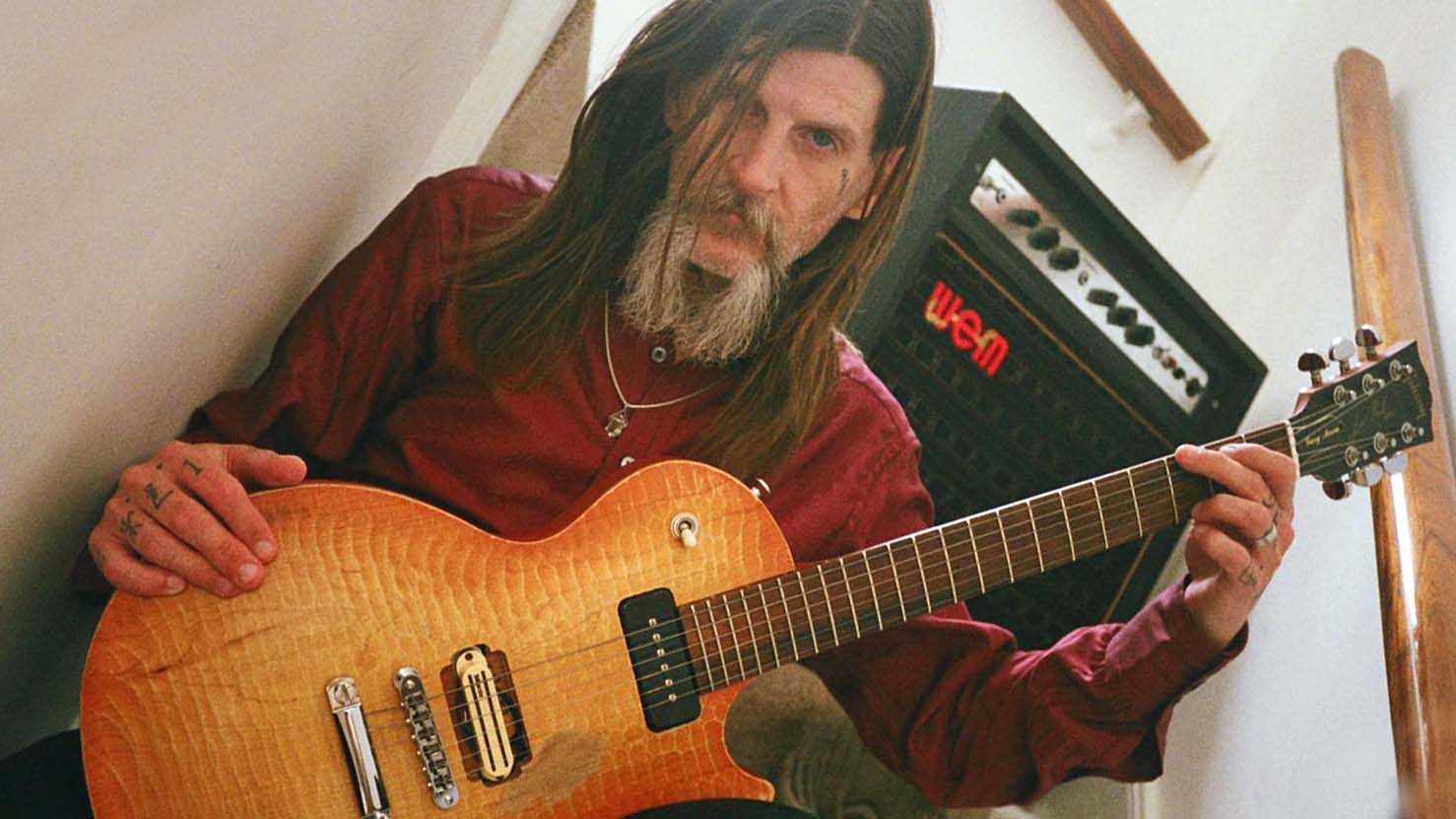

Dylan Carlson’s top 5 tips for guitarists: “Even with repetition and a good riff, songs should have an arc”

Earth's drone-rock legend on going solid-state and why you should never pay more than $600 for a guitar

Dylan Carlson is the sort of guitarist who is capable of shifting our perspective on the instrument.

The Texas-born Seattleite is responsible for mapping out the contours of drone rock with Earth. Formed in 1989, in Olympia, Washington, and named in homage to Black Sabbath, Earth were Carlson's third attempt at putting a band together.

"When I started Earth, I came to it with pretty strong ideas of what I wanted to do in regards to slowed-down metal riffs, repeated for a long time at large volumes," says Carlson.

If Earth were inspired by Sabbath they were to take that inspiration far from the source, with a sound that played out like an abstraction of metal, as though a thumb was on the record and the riffs looped on repeat. It was metal as a vibe, as ambience.

Putting some blue sky between his sound and his influences has been key to Carlson's craft.

"I've never wanted to sound like my influences," he says.

What I get from my influences is inspiration, or songwriting ideas. It's like they've done it: why do you want to do it again?

"What I get from them is inspiration, or songwriting ideas. It's like they've done it: why do you want to do it again? I don't understand that aping. So yeah, I think there are a lot of people who I consider influences but they don't do anything like I do and I don't do anything like them."

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

As a player, Carlson is all about phrasing and repetition. Throughout his career, with Earth and his solo work, he has enjoyed an on/off relationship with the fuzz pedal, as the metal of early works such as Earth 2: Special Low Frequency Version (1993) was augmented by and gave way to a growing country influence. The slo-mo Americana of The Bees Made Honey In The Lion's Skull (2008) marked the apotheosis of the latter.

A discography of such contrasting styles might seem incongruous, but Carlson's songwriting moves with a glacial inevitability, at a tempo where a simply phrased riff assumes an almost cosmic importance. In such a context, all makes sense.

Carlson is in town to talk about Conquistador, a solo LP recorded with Kurt Ballou that's out on 27 April through Sargent House. It's typically Carlson, of a piece with his work on Earth, with chewy blues riffs repeating upon each other.

Carlson uses his guitar in much the same way as John Ford uses his camera, capturing America as both awesome and beautiful, but also inherently dangerous. Like Cormac McCarthy, Carlson writes passages of restorative beauty, all the while maintaining a low thrum of tension, as though this yogic calm could end any time soon.

Carlson's grasp of feel and composition is something any player could use, in all kinds of contexts. So, here, when he talks about his love for old R&B players who play right in the pocket, of the importance of writing songs and keeping on writing, and how inspiration is only really inspiration for you to do with what you please, it's time well spent.

It's a good rule of thumb - to paraphrase Wilson Pickett - to take such wisdom where you find it.

1. Songwriting always comes first

"When I started playing guitar, I immediately started writing some songs. I never took formal lessons or anything like that, so once I learned a few chords I started to write a few songs, but I guess what set me off on the course that I pursued was I’d hear songs and the band would be like, ‘Oh, here’s a good riff,’ and then they’d immediately go to another one - for me, it was always, 'Well, if it’s a good riff, you want to hear it again and again', so why dilute it by jumping around a lot?

My technique or my ability is always subservient to the song, and even with repetition and a good riff, songs should have an arc

"AC/DC are a great example. Malcolm Young took essentially the same however many chords per song - two, three chords - and wrote this incredible body of work with the simplest of materials.

"The guitarists that I really admire are like Steve Cropper, y’know, the guys from the R&B labels, the Stax Records band, Cornell Dupree. They can certainly do leads, but that’s not what they are about. They’re about that perfect riff or lick that you wanna hear over and over and over again. And that’s the core of the song, basically. That’s how I’ve always approached it.

"There are records that I love but, to me, they are records that are made by guitar players for other guitar players, and I never wanted to make an album like that. My technique or my ability is always subservient to the song, and even with repetition and a good riff, songs should have an arc.

"It’s harder when you are working instrumentally because it’s not like verse/chorus, verse/chorus, bridge, outro... There is no lyrical arc, but I feel like the songs should have a musical arc."

2. Live in the moment and leave yourself open to providence

"A big thing for me in the studio is what I call the happy accident, and being able to perceive that. I've had friends who are perfectionists, and I just think, 'God, you must be miserable all the time!' And it just seems like you're never gonna get stuff done, and you're never going to be happy.

"You have to be open. You may have an idea for a record, but it's going to change, and there's reality, and the people you're playing with are gonna be able to add stuff to it that you couldn't think of. With the right people, it's gonna make it better, and what you're ending up with is going to be better than what you had. It's really being open to those moments.

"Recognise when enough is enough. You know what I mean? I think that Pro Tools has had this sort of pernicious effect on music where people are like, 'Oh, we have endless numbers of tracks!' And so they end up burying things, and making things too dense. Most of the great music is deceptively simple. Generally, if we don't get it in three takes then we leave it and come back to it."

3. Learn your music history

"I hate to sound like the old guy, but one of the things I see with modern music is like it seems a lot of bands' influences are bands from two years ago, so there's no depth to their inspiration. Or they decide they are going to play this micro-genre before they even start the band.

I've always tried to make music that's timeless, like it's not of an era, or of a specific time. To me, great music sounds like it has always been there

"Back when I was first going, there were people who were going, 'We're going to do hair metal' or whatever, but it's more like people got together to play music and whatever happened happened. It wasn't like, 'We're gonna be stoner-sludge doom, so we need this kind of gear, and this kind of look.' Everything now just seems kind of like we decide on a micro-genre, and it's just so weird to me. I just don't understand it.

"I also think the audience wants something easy to latch onto, because there's so much stuff out there now. 'Oh, this music matches the identity I want to present. I want to find the music that has the schtick that I can easily adopt.'

"I've always tried to make music that's timeless, like it's not of an era, or of a specific time. To me, great music sounds like it has always been there; it's why so many songs that are overtly political sound dated because things have changed and it's not relevant any more.

"It's funny how a lot of the music made with the latest technology or whatever now sounds really dated because they were relying on technology and the technology has moved on. Like now it's really funny because it sounds really dated even though at the time it was, 'Oh, we're using the latest technology!' Again, it's relying on gear rather than yourself."

4. Don't obsess over gear

"My favourite guitar right now is my Squier Strat, just the pretty much standard, the cheapest Strat, and I put a DiMarzio Cruiser pickup in it. They're great.

"I don't understand paying more than $600 for a guitar. An electric guitar, the prices on them, it's like why? There's no reason for electric guitars to be that expensive. It doesn't make them any better - maybe with acoustics, I don't know. Maybe the more you spend on them the better they are, but I don't play acoustics so I don't know. But electric guitars? As long as it's got a good neck, good pickups, and good bridge and tuners, it's like everything else is irrelevant.

"I still have my Tele [Highway One Series, an entry-level USA-built model]. It's a few years old and it's like a standard Tele, and then I have a DiMarzio Tone Zone T in the bridge. Those are my two main ones now.

You have a lot of choice. I think it has gotten a bit ridiculous. I see some people's pedalboards and I'm like, I don't understand it. You don't need that many pedals

"I had to move house in Seattle, and eventually I want to move here [London], so I did a huge clearing out. I've always felt that if you're not using an instrument then you should pass it on. I don't understand hoarding instruments. If you're not using it then let someone else have a go.

"You have a lot of choice. I think it has gotten a bit ridiculous. I see some people's pedalboards and I'm like, I don't understand it. You don't need that many pedals. I think there's a reliance on them. I always try and keep my stuff down - a compression, an overdrive, and anything that's not either of them I call a wobble box, like a vibrato or delay or whatever. Maybe one of those. I feel like if I have more than four pedals then it's not that I'll be forced to use them but that I'll be relying on them too much.

"My whole rig is solid-state now. I use a Dietz 1x12 cab, that I think has an Electro Voice 12-inch speaker, and then I have an Ampeg 2x10 cabinet, and then I use on one cab a DB-Mark 50-watt head, a little solid-state, and then I have a Crate Powerblock because I usually run two-channel mono.

"I use a Korg Pitchblack tuner, an MXR Custom Comp, an MXR Shin-juku Drive – it was created by this guy Shin Suzuki, he's a Japanese amp tech. He's a Dumble amp tech, and he makes a pedal in Japan called the Dumbloid, which is 600 bucks and is supposed to create a Dumble sound. He got together with MXR to make a cheap version of that. It's basically a Dumble sound. I love MXR's stuff.

"Yeah, it's fun when you've got a huge amp or a stack. It's an exciting thing, and we all grew up with these pictures of Hendrix with the walls of Marshalls and all that, but there were no PAs then so that's why. And Hendrix used effects, but he used them musically. They weren't crutches. It was part of his tone but he was playing large venues with no PA.

"With a tube amp, you're never going to get to the sweet spot on a 100-watt amp in a venue. A perfect example for me was when we opened for Neurosis at Koko, in Camden, and I was playing a WEM Dominator, which is technically a 15-watt amp, y'know, and everyone was raving about how good it sounds but that's because, yeah, the PAs now are good, so if you have a good amp it doesn't need to be a million watts."

5. Practise with purpose

"Usually I start out as if there's a specific technical aspect I want to learn, like when I first started learning pedal-steel bends on regular guitar, the guy in the book talked about if you want to learn something new you practise that for the first 10 minutes, and then go on to the rest. I found that worked really well. At first I was like, 'Whatcha mean I only do it for 10 minutes?' But then the first time, every time you practise, you practise that. When I wanted to learn that I did that.

"And then practising what I call calisthenics, like working on finger ability and that kind of stuff, working on chords or scales, that comes next, and, usually, by the end of it, I'll be like, 'Oh, what's that?' And I'll be working on a song, and that's how it generally goes. I don't woodshed like I used to. When I first came back I would do five to six, sometimes seven hours a day if I could!"

Jonathan Horsley has been writing about guitars and guitar culture since 2005, playing them since 1990, and regularly contributes to MusicRadar, Total Guitar and Guitar World. He uses Jazz III nylon picks, 10s during the week, 9s at the weekend, and shamefully still struggles with rhythm figure one of Van Halen’s Panama.