Will Champion on world domination with Coldplay, new kits and the art of waiting

Coldplay man reveals all on his new Yamaha kit

15 years of touring...

Coldplay have come a long way in the last 15 years.

Head back to 2001 and the band were fresh-faced indie-rock sensations, riding high on the back of anthemic tunes like Yellow and Trouble from 2000’s Parachutes debut.

It was one hell of a landing for the band, and a steep learning curve in particular for Will Champion, who could not call himself a drummer when he first joined frontman Chris Martin, guitarist Jonny Buckland and bassist Guy Berryman on the kit.

It’s been basically 15 years of touring...

A decade and a half on, he has become one of the world’s most accomplished drummers. Coldplay are now one of the biggest bands in the world, and we bear witness to their popularity as 55,000 fans go mental in Glasgow’s Hampden Park stadium as Will and co deliver a storming set comprising hit after hit, with blasts of fire, volleys of fireworks and clouds of confetti adding to the kind of spectacle that only the hugest of bands can command.

Although given that time is short in a hectic schedule that, after all, was supposed to include a round of pre-show cricket with their mate Shane Warne, when it’s time for our audience with the drummer, we decide to just jump straight back to 2001 and our last interview with Will – just after the release of their first runaway-success of a debut, Parachutes.

Will, last time we interviewed you, you spoke about getting to a point where you needed to learn more technique to keep up with the rhythmic ideas you had in your head... so, how did that go?

“[Laughs] It went very well, fortunately! First, I’ve done a lot of practice since then! It was a steep learning curve, definitely, but there is no better place to learn than on tour. I think where I came a little bit unstuck initially was going straight into the studio, and I found that difficult. I’d never been in a studio before and I’d played a few gigs live but I think if you give a lot of energy in a performance then you can be forgiven for not having great technique – in the studio I think it becomes obvious pretty quickly if you don’t know what you’re doing. So after we spoke those many moons ago, it’s been basically 15 years of touring and so a lot playing and a lot of improving, a lot of watching other drummers as we were playing with other bands, soaking up as much information and as many ideas as possible.”

The occasional big haymaker makes a difference, and people think, 'Oh he's really into it.'

By the second album, A Rush Of Blood To The Head, you’d clearly all improved massively as musicians – is it true to say you’d spent a lot more time working on your technique by then?

“Definitely, I think it was honed over a huge amount of touring. It’s funny now when I listen back to those records, on the rare occasion I do, I can really tell what I was listening to, who I was influenced by. Around the time of Rush Of Blood To The Head, we started to get into Echo & the Bunnymen, and we started to get into Neu!, Krautrock, and Kraftwerk – just starting to sow those seeds... we were quite free, there was a lot of acoustic-y stuff and soft sounding rhythms on the first record, and on the second one we discovered a way to play with slightly more of an edge, but still getting the emotion of the song across.”

Did that suit your playing style better? You’re obviously a very hard hitter!

“Not initially, that’s the thing – I think all of these things are influenced by your surroundings. As you start to play bigger places you become aware of the need for it to be visual as well and I think that’s something we’ve always thought a lot about in our band, how it comes across on stage. Jonny and Guy have got a lot to do technically so it means they can’t run around a lot. And at the time of Rush Of Blood Chris was at the piano a lot and I felt that the show would benefit and the band would benefit from having something a bit more visual, so arms flying around a bit.

Right off the bat I didn’t have the confidence to play loud or heavy, I just was focussed on not f**king up basically!

“Because there are wonderful drummers but if you’re standing at the back of a big arena, sometimes you can’t tell if a drummer’s even moving! These amazingly gifted technical players, and they’re wonderful to listen to, but I want to be able to see what they’re doing and if you don’t have cameras on the drums then the occasional big haymaker makes a difference, and people think, ‘Oh he’s really into it.’ Right off the bat I didn’t have the confidence to play loud or heavy, I just was focussed on not f**king up basically!”

Would you say there’s a trade-off there between chopsy playing and the showmanship needed for the big stadium gigs?

“There are elements to it, I agree with that – there’s less room for subtlety in bigger arenas. But having said that there’s a lot of stuff that we’re able to do now with using drum pads and sequencers and things like that, that really provides a lot of that sort of nuance but with clarity. That’s one of the great things we’ve discovered through our sound engineer, really boosting the kit with electronic samples and you can then have power and clarity but with intricacies and a bit more detail. But it definitely is the case sometimes, if I was to listen back to just my drum performance throughout a whole show, I’d be able to pick holes in it, every song, but it’s really about the end product. What is happening in the stadium, with these 80,000 people – are they enjoying it? That’s really the ultimate. If someone says, oh, he was a bit sloppy today, as long as people are singing and people are enjoying themselves, that’s what gets me going.”

When you go into the studio, and when you’re in the writing process, do you feel that you are able to do a little bit more technical drumming, and is it always in your mind then, how is this going to come across when we go to play it live?

“Yeah definitely. It’s funny, I was thinking about that when we were recording the last album. We were doing a lot of drum takes, but I would be trying to put down a drum pass and maybe in two or three takes [they’d be], ‘Yeah I think we’ve got it,’ and I would be suspicious immediately because previously, on the first album, it would be 25 or 30 takes before I got anywhere near it.

“So I thought to myself, well actually you have been playing the drums most days for the last 15 years, it’s no surprise you’re getting a little bit better! It’s quite nice to have that moment, to think, actually I can do this. It might not be a particularly difficult drum part but there’s no reason I can’t do it in one or two takes. But initially I’m always suspicious, I always doubt that it’s possible to do it quickly and efficiently and play it really well. It’s nice to surprise yourself.”

Make them wait...

Did you find initially, because you were not a drummer first and foremost, that you had four other drummers in the room – the band and the producer – all saying ‘do it like this’?

“We always talk a lot about each other’s parts because the song has to work, that’s the most important thing, to support the song. So there’s always a kind of, ‘Well, can you try that?’ or, ‘how about this?’ or, that was a bit too complicated, or that was a bit uninspiring, can we try that, can we try this, but always positive, you know? We enjoy exploring and trying new stuff, trying to be inspirational to each other and help each other create something new.

That’s my trademark – wait. Keep waiting... keep waiting... and then at the last moment possible come in and steal the limelight at the end!

“I find that helpful actually, I don’t find that I can trust my ears during a drum take in a studio, I don’t know whether I can tell it’s great, so you rely on other people to tell you that. I have great memories of being in the studio and finishing a take, thinking I wasn’t sure about it, and then looking up and seeing the boys in the control room, everybody thumbs-up. It’s a really great feeling, so I think I definitely rely on other people to let me know whether what I’m doing is good enough.”

What tracks do you think show you at your technical best, or best ‘feel’-wise?

“I’m really proud of the things where it’s absolutely boiled down to its bare essentials. I’ve never really been one for overly intricate patterns, so I consider it a success if I’ve managed to do as little as possible, but make it absolutely convincing. So songs like Viva La Vida is just a kick drum and a bell, and a little bit of timpani here and there, but it’s so simple.

“We tried so many different things with that, four-beats, rock beats, everything – but nothing worked. So it was a case of you’ve got to strip absolutely everything away to its very, very bare minimum. There are so many intricacies on the violins and the melodies and everything I just felt

it’s got to be absolutely simple with no frills, just support the song.”

There’s a case to be made more for what you don’t play in a song though isn’t there? On a track like The Scientist you come in late but it’s really effective when you do.

“That’s my trademark – wait. Keep waiting... keep waiting... and then at the last moment possible come in and steal the limelight at the end!”

"When I grew up, melody was the most important thing to me.

So you obviously aren’t one to overplay, but early on were you tempted to through youthful enthusiasm?

“I’m not sure that I was. I think I was nervous, really, I never felt I was good enough to show off, so that’s partly where my style has come from, I think, just wanting to support the song as much as possible – whether that’s by not playing for 75 percent of the song or by playing something very simple. But it was a feeling of not wanting to intrude on the song.

“When I grew up, melody was the most important thing to me. More than lyrics, more than rhythm, it’s just melodies. So whatever I could do to push that to the front, to help that along was what I wanted to do. So the occasions where I would, when we played live, try something, more often than not it would fail! So there’s a way to deal with this, which is to not bother! Just keep it simple!”

On the last big tour there was something about the front five songs that absolutely annihilated me.

Some of your songs, like Clocks or God Put A Smile On Your Face or Politik, the beats are really quite relentless, so that must take a lot of stamina and put a lot of strain on your wrists?

“Yeah definitely, and my forearms, you get a build up of lactic acid in your forearms and then you can’t grip any more, and you start to lose control of the stick and you’re just holding on for the last beat, between my finger and thumb, when you can hit the crash cymbal! I find that it depends on the pace of the show.

“On the last big tour, on the Mylo stadium tour, there was something about the front five songs that absolutely annihilated me, the first song, coming in cold and playing Hurts Like Heaven which is quite fast, it just left me struggling. I was always playing catch up from that. But this one, maybe ’cos I’m fitter than I was, I’ve been trying to keep in good health, I find the pace is less demanding and because we have a lot of the big numbers towards the end I feel like I’ve got enough left in the tank to do that justice.

“But in previous years if you start big it’s very difficult to sustain and with a lot of singing as well... in Viva La Vida I’m standing whacking a bell and timpani and a bass drum and singing at the top of my range for the whole of the outro, that’s normally when I feel like, ‘Christ, that was hard work!’ And it’s really lungs-bursting, but I love it, I absolutely love putting that effort in because again it translates in front of a lot of people and people think, he’s really going for it, he’s really giving it everything – and that’s what makes a great show.”

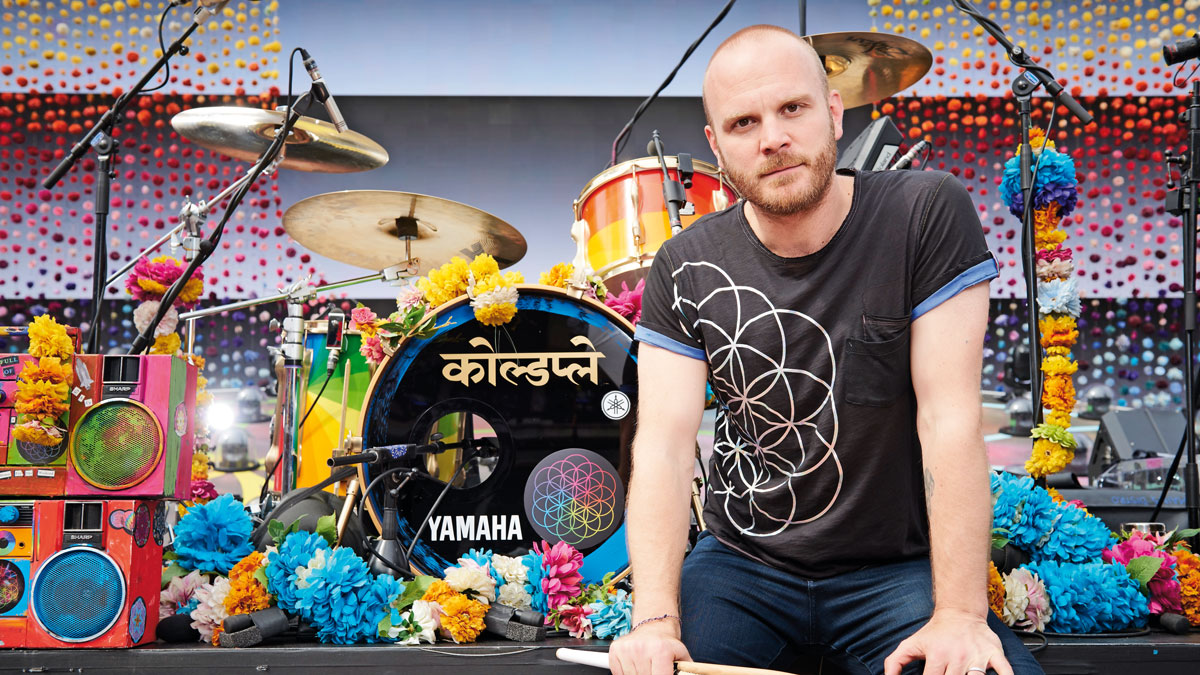

Will's kit

So tell us about your new kit...

“It is the new Yamaha Recording Custom. Yamaha has been lovely enough to help me out from the very beginning. I’ve been playing maple kits for the best part of 10 or 12 years. My first kit was a Yamaha 9000, but ever since rush of Blood I’ve been playing a maple kit which I’ve loved in varying sizes.

“We had a huge bass drum for Rush Of Blood and then it started getting smaller. We had a few months after we’d finished the record [A Head Full Of Dreams] before we started to tour where we could go in and really dig into the live sound and how best to translate what we’d done in the studio to a live setting, specifically knowing we were going to be in stadiums. And there was a feeling that we could improve our live sound. As obviously the triggers is one side of it but the source sound, the kit, we wanted something that would not sound out of place with a lot of the modern sample sounds we were using.

“So we asked Gavin [Thomas, Yamaha Drum Product marketing manager] what he had, and we got the new version of the maple and we lined that up against my old maple kit, and he said, we’ve got this new one coming up, the new recording custom, which is a top secret, ‘Project X’ sort of thing. So he brought it down and we had them all lined up, and specifically the kick drums, and spent two or three days just putting them through their paces and recording stuff with them and then listening back through eight different speakers and in different contexts, and it just seemed to have the right balance of weight and control and precision, which was the thing that was lacking with the maple.

“That’s a bit more reverberant and woolly, which was great and suited me for many years, but it was a great opportunity to try something new against some of the other drums out there. Even with blind listens – Dan our sound engineer wouldn’t tell us which was which – pretty much unanimously it was the best sounding one, because it had a lot of front-end, which is crucial to cut through, but also some serious weight and depth in the kick drum, and that really sort of swung it. Gavin said that they could get a couple of kits ready in time for this European tour and we obviously jumped at the chance.”

Drums

Yamaha Recording Custom kit: 22"x16" bass drum, 13"x9" rack tom, 16"x15" floor tom; various snare drums

Cymbals

Zildjian: 20" K Heavy ride, Brilliant finish; 18" A Custom Medium crash (x2); 14" K Custom Dark hi-hats

Plus

Heads: Remo Coated Ambassadors; ProMark Hickory wood 5A drum sticks, Yamaha hardware, Roc N Soc drum throne; e-drum pads (x2); electronic percussion pad.