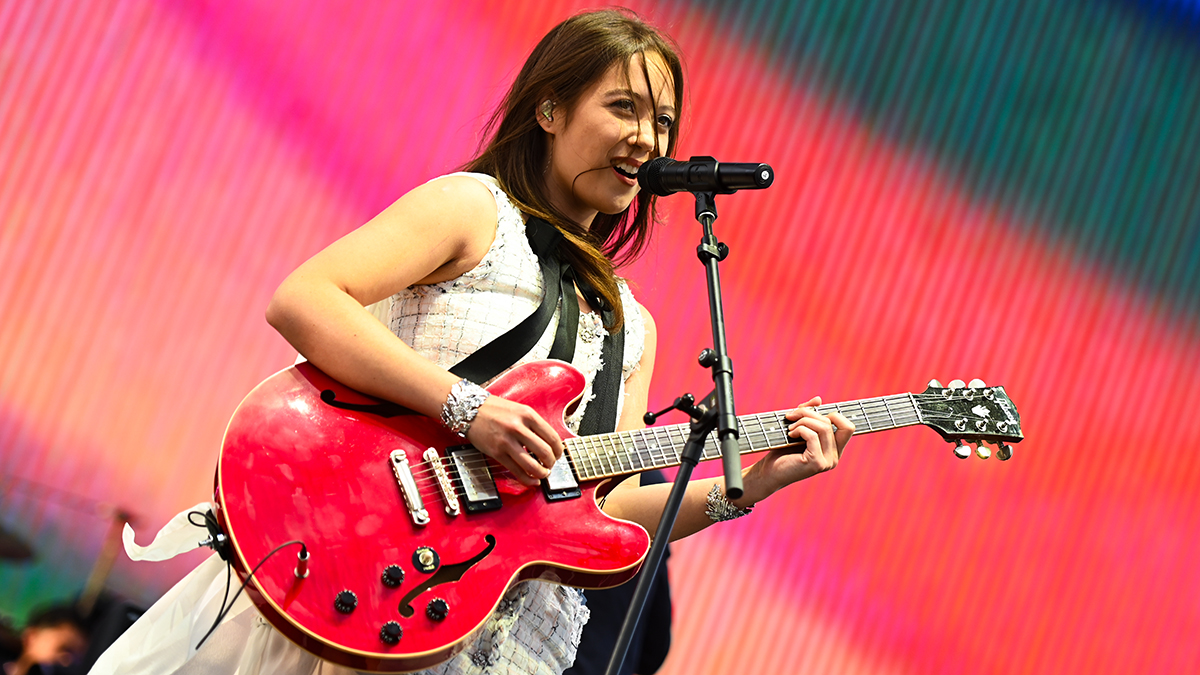

Steve Ferrone during a performance by Tom Petty And The Heartbreakers in Sacramento, California, 2006. © Tim Mosenfelder/Corbis

Steve Ferrone has sat in the drummer's seat for Tom Petty And The Heartbreakers since 1994. But the British-born sticksman is still seen by many as 'the new guy.' It's a label he's grown accustomed to over the years. "I'm always the second man asked to the dance," he says, laughing. "But I'm not complaining because I've been to a lot of nice dances."

And that dance card has been full ever since Ferrone replaced the late Robbie McIntosh (not to be confused with the guitarist of the same name) in the Average White Band in 1974, right as the group was releasing their breakthrough smash Pick Up The Pieces. Over the past four decades, Ferrone's impeccable taste, timing and groove have paid off handsomely: he's been 'the new guy' for Eric Clapton, Duran Duran, Peter Frampton and The B-52s, among others, and has played on countless sessions for everyone from Johnny Cash to Michael Jackson.

Even so, when it comes to touring bands, does he mind being thought of as 'the new guy,' or even 'the replacement'?

"Not at all," he says, again chuckling good-naturedly. "I've replaced Stan Lynch in Tom Petty And The Heartbreakers. I've replaced Phil Collins with Eric Clapton. I've replaced Roger Taylor with Duran Duran. There's a few choice ones right there. No, see, these drummers have played on amazing records, and I have a tremendous amount of respect for their work. To be asked to go in and sit down and play the parts that they established, I'm flattered and honored. Also, I guess it means that, on some level, I'm that good - or at least in somebody's mind I am."

Having now clocked in 16 years as a member of Tom Petty And The Heartbreakers, currently touring behind their latest release Mojo, it's doubtful that Ferrone will be abdicating his drummer's throne to anybody else in the near future. "It's a wonderful group of people in this band," Ferrone says. "Tom and Mike Campbell are such brilliant writers. No, I'm quite happy to be a Heartbreaker." He thinks for a second. "That always sounds funny, doesn't it? I'm a 'Heartbreaker.' Of all the bands with great names, this one's right up there."

In the following interview with MusicRadar, Steve Ferrone talks about playing with Tom Petty And The Heatbreakers, along with some of the other illustrious names on his CV. He also discusses his approach to playing, and it's one which involves, oddly enough, the art of the dance.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

What is general philosophy about drumming? Do you have one?

"What I like to do is feel the song - I see it and figure out what I like to call the 'light and shade.' When I was a child, I was a tap dancer, and I remember a big part of our instruction revolved the light and shade of certain routines. I see drumming the same way I see dancing. It's all dynamics.

"Because of my tap dancing, I can visualize a piece of music and feel it physically. Basically, I can sit down with a band and pretty much play a song without ever having heard it before. I'm not saying I play it perfectly the first time. [laughs] But I have a sense of the flow, the dynamics, where the choruses and verses are going. If you have rhythm - and let's face it, dancing is a great starting ground for a musician - you're usually able to know how a song should go."

I would assume this helped in recording Mojo, which is the most 'jam-oriented' album the band has ever done.

"Well, yeah, we recorded the whole thing live pretty much. Tom would come in and start playing a groove, and I'd start playing along. He didn't present finished demos or anything. The songs fell together during rehearsals. That's the way it's been with us for a while.

"Songs used to develop during soundchecks, too, although we rarely do soundchecks anymore. With the new technology like Pro Tools, we just record the sound from the gig before and adjust the levels to the next room. Soundchecks are kind of a thing of the past now."

What kind of direction do Tom and Mike Campbell give you? Or do they give you free reign to come up with your parts?

"They give me free reign…until I do something they don't like! [laughs] Their music is pretty straightforward, so if I do something too complicated or come up with a groove that just won't fit - anything that gets in the way - that's when they'll say something. And then I'll say, 'Fine, I just won't do that again.'" [laughs]

When you were asked to join, what specifically did Tom tell you was the reason? What made you the right guy to replace Stan Lynch?

"He never really told me, and I never asked him. I got a call to go out for an audition, but I wasn't told who it was for. This was in 1994. So my gears were turning…'Who could it be?' It was all very top secret, you know? But then I showed up at this studio and there's Tom Petty and Mike Campbell sitting there. Well, I figured out pretty quickly who I was auditioning for."

What did the audition consist of? Did you have to play through some of Tom's hits?

"Well, I should stress that I'd worked with Mike before - he and George Harrison; in fact, I'm pretty sure that George recommended me for the gig. So we started to play You Don't Know How It Feels, and that felt pretty good. Then we listened back to what we'd played and Tom said, 'Wow, what a difference a drummer makes.' Then he turned to me and said, 'Don't worry, Steve, you've won.' [laughs] And that was it."

How have you adapted your style to the older songs in Tom Petty's catalogue? Some of the material that Stan Lynch played was quite energetic. I'm thinking of songs like American Girl.

"Yeah, well, that song speaks for itself. It has a pattern that is very recognizable and I don't really change it at all. The kick pattern, especially, is very important to play right. The song has a swing to it.

"My job isn't to re-arrange songs that are etched in people's minds. But the newer songs, the ones I've played on, they're mine, if you will. So I don't have to adapt my style to fit them; my style is already a part of them."

Who do you listen to in the band? Do you listen to Tom's vocals? Ron Blair's bass lines?

"I listen to the whole thing. I let the music fall all around me and I make it work. If Ben [keyboardist Benmont Tench] plays a nice little line, I try to leave space so it can be heard. If Tom hits a certain vocal line and really punches it, I might reinforce it, but I don't get in the way. I don't try to set the tone and the tempo of the band; I let them guide me and I keep it all together. The band works really well as a team.

"However, you mentioned vocals: I will sing along as I play. It's not just 'cause I like to sing [laughs]; it's because I'm checking the tempo. If you're shifting things around too much, particularly with songs that are so dependent on the vocals, then all you're doing is messing things up."

You play with a traditional grip. Have you always done so?

"No, I started out with a matched grip, and I switched when I was about 18 or 19 years old. I remember watching this French drummer who played with a traditional grip, and I was very impressed with his ability to get all of these grace notes in. The big thing was figuring out how to incorporate the traditional grip but still have a strong backbeat. So I worked out a way to play traditional but power down the stick with my thumb - which is why I have a very messed-up thumb now!" [laughs]

Let's talk about your tenure with Eric Clapton. What was that like? What kind of directions did he have for you when it came to what he wanted from the drums?

"His whole thing was, 'Make me play.'"

"Make me play."

"Yeah, he wanted the band to kick his butt. You know, it's a hard job to be 'Eric Clapton.' He's gotta go out there every night and live up to this legend. He has all these solos to play, and he's gotta blow people away. It's a lot of pressure. So he would just say, 'Steve, go out there and play your ass off.' He looks for fire. I think he really liked being pushed. It helped keep him on his toes, I think."

Playing with Eric, you performed material from all of the eras of his career. How did you handle the Cream material? You and Ginger Baker have styles that couldn't be more different.

"Absolutely. I would just sort of grab it and make it mine. I played Sunshine Of Your Love totally different. I took a hint of his groove, but there was no way I could match what he did. I didn't even try.

"All drummers have their own particular quirks - some you try to work with and others you can't. When you're talking about somebody as flamboyant on the drums as Ginger Baker, there's no way you can play like him.

"The point is to take the essence of what he did and use that. Again, Eric's whole thing was, 'Play with fire, Steve. Give me everything you've got.' He didn't want his musicians to play it safe. And you can still play a groove and be non-flashy while giving the music everything that's inside of you. Sometimes that's the hard part - playing with heart but not making it all about yourself."

On a somewhat related note, you played with both Eric Clapton and George Harrison when the two toured Japan together in 1991. It was basically Eric's band backing up George.

"That's right. What an amazing time."

OK. How hard was it, when playing Beatles songs with George, not to try to re-create Ringo's parts?

"I didn't really think about it. George told me what songs to listen to, I listened to them and we played them. What I did was what I always do: I listen to the song, I get the groove, I figure out the key elements and then I do my thing."

How was George to work with?

"Oh, he was wonderful. What can I say? He was a great guy. A tremendous human being. I walk past his star on Hollywood Boulevard a lot, and every time I do I say, 'Hey George, how ya doin'?' What a sweet man he was."

One other mega-famous artist you worked with was Michael Jackson. Tell me about that experience.

"Oh, it was great. I was hired to play on a couple of songs, and one of them was Earth Song. I was working with the producer Bill Bottrell. So we're in Westlake Studios in Los Angeles, working on the song, and I turn around and there's Michael Jackson. It's like he materialized right next to the drum kit."

Wow. What do you say? "Hey Mike"?

"Yeah, basically. [laughs] And what was funny was, he looked at me and said, 'Steve, can you dance?' And I go, 'Well, are you asking?' [laughs] Maybe he could tell by the way I played, I don't know.

"What was interesting about doing that song was that Michael wanted me to play electronic drums - that was the big thing in those days. And I said, 'Michael, the song is called Earth Song. You've got to have real drums on there.' I could tell he was hesitant, but we cut a deal to do it both ways.

"He listened to the electronic drums and liked them, and I could tell he was about to go with that track, but I reminded him about our deal. So I went in and cut the same track on acoustic drums. He listened back and started movin' around, going, 'Yeah, yeah! That's it.' And that's when I told him, 'There you go, Michael. Now you've got a true Earth Song! [laughs] The acoustic drums won out in the end."

Liked this? Then read Mike Campbell on 30 years with Tom Petty And The Heartbreakers

Connect with MusicRadar: via Twitter, Facebook andYouTube

Get MusicRadar straight to your inbox: Sign up for the free weekly newsletter

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.