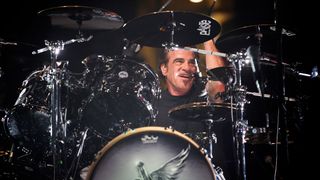

Tico Torres's top 5 tips for drummers

Bon Jovi man on audience energy, tuning your kit and more

Tico Torres's top 5 tips for drummers

They may now be 33 years and 13 albums in, but there’s no sign of Tico Torres and Bon Jovi slowing down.

New album This House Is Not For Sale is nailed on to be a smash hit worldwide, and Torres has an inkling of just why the New Jersey stalwarts have stood the test of time.

“We all still want it,” he says on the eve of the record’s release. “We’ve been through a lot together. We’ve had all the trappings of fame, fortune and everything that goes with it. We got past that and realised we’re doing this because we love working together.”

We’ve had all the trappings of fame, fortune and everything that goes with it. We got past that and realised we’re doing this because we love working together.

Thanks to the oodles of industry points that Jovi have acquired during their multi-million unit shifting career, This House Is Not For Sale was able to be recorded away from the shackles of major label pressures.

“In the earlier days we had a lot of pressure from record labels to put out hit album like bang, bang, bang,” Tico explains. “You can get caught in a whirlwind because as a young band you don’t know any better.

“In the 90s we started realising that we didn’t need to work like that constantly and we could pace ourselves more. There’s a lot of things in life that will influence how you work. I think it’s important to smell the roses every once in a while.”

Tico took a little time out, not to smell the roses, but to offer up his top five tips for drummers.

1. Use the audience's energy

Going from clubs to stadiums is like night and day. You’ve got to think about the energy that people put out.

If you have 100,000 people there then you will be affected by the energy and it exhilarates you. The band plays with the audience, the audience is a huge part of a performance. That adrenaline can push the band faster and that happens to every band.

If you have 100,000 people there then you will be affected by the energy and it exhilarates you.

I have to be mindful as a timekeeper to hold things back. It might feel a little slow but it will sound fantastic.

Having the interaction with a big audience is great, there’s nothing like that. Sure, I like playing small clubs as well, but I really like playing for the big crowds.

Doing some of the older songs, they always feel fresh. I’ve never felt like, ‘Jeez, I’ve got to do this song again.’ It’s a different day and a different audience. When I was growing up I wanted to see the bands play the songs they were known for, so I get it. I think our songs hit a nerve with our audience.

We try to always reinvent ourselves because life doesn’t sound still, but it’s wonderful to still play the songs that got us to this point and see the audience reaction. I throw the odd accents into the old songs so they grow but we stay faithful mainly to the parts.

2. Learn to tune your kit

I tune in thirds and fourths. If you can play Post Time, the music at the beginning of horse races, if you can play that on the kit then I have tuned the kit to the way that I want it. That’s my gauge.

I think tuning is very important and it is something that you can change from song to song. I like to give the song whatever it merits sound wise. Predominately that is the tuning and also changing out the snare drums. I might go for a thicker or edgier snare sound on some songs.

It’s a wonderful advantage to change things up like that. Years ago I had a 1930s Slingerland drum that was fantastic and I used it on Slippery When Wet, but I had to retire her. A drum of that age, the hoops could not take the pounding. It’s painful to do that.

3. Be open to ideas

In the studio you’re creating something so the best mindset to have as a band is to never say no to an idea.

As soon as somebody says no that takes the idea away and that idea could have been cultivated into something. If it works that’s fantastic but if you don’t try and you say you don’t like something then you have killed the idea.

The drum parts will start with me but if somebody suggests something to me I will try it. They might take you in a different direction and it could really work.

I remember years ago when I would do sessions a producer might ask me to play a certain rhythm rather than the part that I am playing. They might ask you to put this roll or that roll in there and you’ll try all these different things but if their ideas aren’t working I will know in my head that my original idea worked.

So I would go through this process for 20 minutes and then come back to the original beat that I did and the producer would say, ‘Oh yeah, that’s it!’ That’s a little studio trick.

4. Don't be afraid to take a break

I need to get away from drumming after a long tour and then come back fresh.

When it’s time to go again I get into a routine where I play a lot. Or sometimes I might work with another band, that works as well because it’s something different. That helps keep you greased, you don’t want to get rusty.

But like I say, sometimes it helps to take that break and freshen up. That comes with maturity. When I was young I was playing every waking moment but that is important when you’re young because you’re learning.

The body ages and I look in the mirror and think, ‘Jesus, I’ve aged,’ but for some reason on the kit I still feel like I’m 26.

I rely on my 16 year old inner self a lot. The body ages and I look in the mirror and think, ‘Jesus, I’ve aged,’ but for some reason on the kit I still feel like I’m 26.

That drives me through a show even if I’m really tired after two hours, sometimes we even go for three hours. I just tune into that. It helps that it’s hard to grow up when you’re a musician.

5. Get out there and play

When I was growing up I would go and see lots of music, tonnes of jazz and r’n’b. I was a regular at the Fillmore East. They’re you’re study years.

Everyone gets rusty when you take some time off but as you get older you can brush that off pretty quickly. I was lucky to grow up in New York City.

Elvin Jones was my mentor, so was Joe Morello, Tony Williams. I could have conversations with these guys. I played a lot of jazz and r’n’b in New York and that gave me a better knowledge of rhythms and polyrhythms. Even if you don’t use those in your music having that knowledge will help you know what you should and what you shouldn’t play.

I played with as many bands as I could. Sometimes I’d be with four or five bands. That variety of music helped tune my ears.

I played with as many bands as I could. Sometimes I’d be with four or five bands. That variety of music helped tune my ears. It helped me play complementary rhythms with the other musicians.

To play with as many guys and as much diversity as you can is the biggest piece of advice that I can give. With time you learn the importance of playing to the song. I’ve always wanted to be a musician that plays to the song rather than being a drummer’s drummer.

Rich is a teacher, one time Rhythm staff writer and experienced freelance journalist who has interviewed countless revered musicians, engineers, producers and stars for the our world-leading music making portfolio, including such titles as Rhythm, Total Guitar, Guitarist, Guitar World, and MusicRadar. His victims include such luminaries as Ice T, Mark Guilani and Jamie Oliver (the drumming one).

"They said, ‘Thank you, but no thank you - it’s not a Monkees song.’ He said, ‘Wait a minute, I am one of the Monkees! What are you talking about?’": Micky Dolenz explains Mike Nesmith's "frustration" at being in The Monkees

“There’s nights where I think, ‘If we don’t get to Paradise City soon I’m going to pass out!’”: How drummer Frank Ferrer powered Guns N’ Roses for 19 years

"They said, ‘Thank you, but no thank you - it’s not a Monkees song.’ He said, ‘Wait a minute, I am one of the Monkees! What are you talking about?’": Micky Dolenz explains Mike Nesmith's "frustration" at being in The Monkees

“There’s nights where I think, ‘If we don’t get to Paradise City soon I’m going to pass out!’”: How drummer Frank Ferrer powered Guns N’ Roses for 19 years