The history of big band and swing drumming

How the stars of the Swing Era defined the drummer's role and created the modern drumset

The birth of swing

'It Don’t Mean A Thing (If It Ain’t Got That Swing)’ declared Duke Ellington in 1931. The dawn of the 1930s was a tumultuous time in the United States. The Great Depression, Prohibition and racial segregation was the unlikely backdrop for the birth of swing, the music of integration and celebration.

In the early 1920s the epicentre of jazz migrated from its birthplace in New Orleans up to Chicago, as key figures like Louis Armstrong moved north. The dominant style was Hot Jazz, later known as Dixieland, played by groups of up to seven musicians all improvising in unison.

Out of the speakeasies

In 1924, bandleader Fletcher Henderson brought Armstrong to New York and the Big Apple became the new home of jazz. The repeal of prohibition in 1933 helped to bring jazz musicians out of the speakeasies and into dancehalls.

Duke Ellington led the house band at Harlem’s Cotton Club from 1927, where they backed up cabaret performers, vaudeville acts and singers. Ellington’s orchestra grew to 15 members, a template for the big bands of the swing era.

It fell to white bandleader Benny Goodman to take the emerging swing style to the masses

But, in racially-divided America, it fell to white bandleader Benny Goodman to take the emerging swing style to the masses. On 12 August, 1935, the Benny Goodman Orchestra was playing at LA’s Palomar Theatre with the flamboyant Gene Krupa on drums.

When the audience met their restrained tea dance tunes with polite applause, Goodman launched the band into a set of hard swinging arrangements he’d bought from Fletcher Henderson. The dance floor erupted and the Swing Era was off and running.

Swinging drums

The importance of the Swing Era to the development of both the drummer’s role and the drum kit itself can hardly be overstated.

The Hot Jazz of New Orleans was a blend of blues, ragtime and the music of the city’s marching brass bands in which the drummer kept time primarily on the bass drum, playing two beats to the bar, and snare.

The trap kits of the time (short for contraption) comprised a bass drum, snare drum and then an array of temple blocks, woodblocks, cowbells, a tambourine and small cymbals all mounted on the hoops of the bass drum.

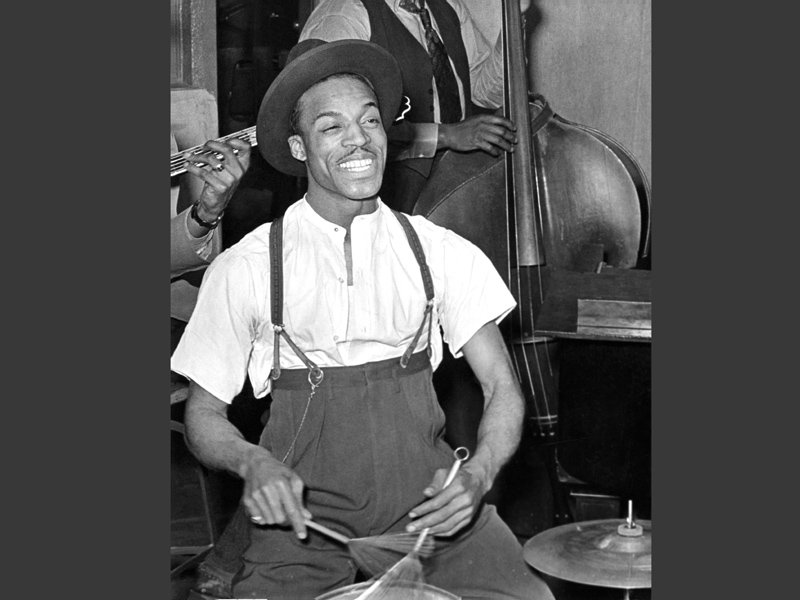

Inspirational Chick Webb

This was essentially the set-up used by one of the early pioneers of swing drumming, the great Chick Webb. Born in Baltimore, Webb suffered from tuberculosis of the spine as a result of which he never grew to full height and suffered poor health throughout his life.

He was originally encouraged to try drumming to build up his strength and his fiery style inspired every player who followed in his footsteps, with everyone from Gene Krupa to Buddy Rich and the UK’s own big band master, Pete Cater, singing his praises.

“The guy you can’t ignore is Chick Webb”

“The guy you can’t ignore is Chick Webb,” says Pete about the birth of swing drumming. “Chick Webb’s records, considering he was this little, disabled guy who could barely reach a drumset, they sound incredible even now. The fire and the drive and energy this guy was able to create behind the drums, you can absolutely hear where Buddy Rich was coming from.”

Cut by a better man

With the support of Duke Ellington, Webb had his first engagement as a bandleader in 1926 at the Black Bottom Club and his band regularly took on other orchestras in the battles of the bands that were popular in the ’30s, frequently mopping the floor with the competition – “I was never cut by a better man,” said Krupa after Webb’s band demolished the Goodman Orchestra at the Savoy Ballroom in May 1937.

One of Webb’s key innovations was to switch from the two beats to the bar of Dixieland to driving the band playing 4/4 on the bass drum. Webb died in 1939 but his legacy lives on in every swinging drummer to follow in his footsteps and, as if that wasn’t enough, he launched the career of a young Ella Fitzgerald.

Changing time

The next major leap forwards was shifting the timekeeping from the bass drum and snare to the hi-hat.

The Low Boy, introduced in the early 1920s, was two cymbals operated with a foot pedal. When it reached a height where it could be played with the hands it became known as the High Boy or the Hi-hat.

Jo Jones, playing with the Count Basie Orchestra, led the way. “The drum kit as we know it came into being with the swing era, particularly the hi-hat,” says Pete Cater. “It was Jo Jones who showed us all what to play on it.” Jones’ techniques included taking his right foot off the bass drum pedal and tapping his right heel on the floor while keeping the time going on his hi-hats, and playing time with his right hand on the hats while tapping out a counterpoint with his left hand on the stand itself.

Early ride time

Jones continued to innovate throughout the swing era. While the switch from keeping time on the hats to the ride is considered a defining trait of bebop, there are recordings of both Jo Jones and Dave Tough playing time on their rides from as early as 1940, on tracks like ‘Tickle-Toe’ by Count Basie and his Orchestra with Jones, and Bud Freeman’s ‘Shim-Me-Sha-Wabble’ featuring Tough.

"It’s all baby steps and this is what the historians tend to forget"

“All this development of the instrument and all the history is incremental,” says Pete. “It’s all baby steps and this is what the historians tend to forget. There was certainly time being played on ride cymbals prior to Max Roach and Kenny Clarke and the bebop pioneers.

"Of course a lot of the early bebop pioneers played on swing and more mainstream jazz recordings; think of Sid Catlett and Cozy Cole, they recorded with Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker but we tend to think of them as swing players. The boundaries are very blurred.”

Drummin' man

What is beyond dispute is that the evolution from the trap kits to the modern drumset was driven by Gene Krupa.

Around 1936 Krupa’s father called up Ludwig looking for a new set for his son, already an established star with Goodman, but met with indifference so he rang the Slingerland Banjo & Drum Company after seeing them in the phonebook.

With the urging and guidance of Krupa, Slingerland introduced fully tuneable toms for the first time, created the famous Radio King line of drums, and took away the blocks, bells and whistles of the trap kits.

Krupa's configuration

The configuration Krupa used – snare, bass drum, mounted tom, and one or two floor toms – remains the standard to this day, while his White Marine Pearl finish became ubiquitous amongst his contemporaries.

The place to buy Slingerland drums in New York was Bill Mather’s Drum Shop on 314 West 46th Street, and it was Mather who first removed the hoop mounts used for the rack tom and cymbals and swapped them for the shell mounts favoured by Krupa.

"Krupa had everybody beat with his charisma"

“The whole persona of the big band drummer all stems from Krupa,” says Pete. “He wasn’t the greatest player of his time, although he was right up there at the top of the pile.

"You’ve only got to listen to him and Buddy Rich side-by-side to hear who had the greater speed and technique, but where Krupa had everybody beat was his charisma and his innate skill of making the big band drummer/leader a viable commodity to the broadest possible commercial audience.

"When you think of a drummer as being a bona fide star on the instrument, what Krupa did has never been surpassed.”

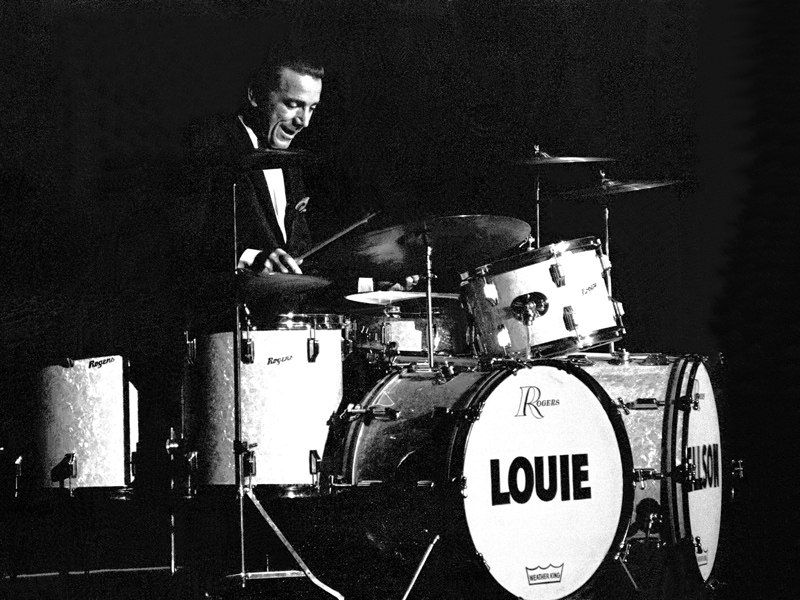

Double the fun

While double-kick playing is commonly associated with metal drumming, it was introduced to the world by swing legend Louie Bellson, who came to prominence when he won a drumming competition sponsored by Gene Krupa as a teenager.

“Louie is universally cited as having had the idea for the two bass-drum set,” says Pete. “Interestingly, Ray McKinley, who had a long association with Glenn Miller, appeared in a Slingerland advert with two bass drums when he was playing with Will Bradley’s band in the late ’30s. He used to call them his Boogie Woogie Bass Drums.”

Ellington insists

Bellson took over from Sonny Greer in the Duke Ellington Orchestra in 1951. While playing two kick drums never really took off in swing as it would later in fusion and metal, Bellson’s tenure with Ellington clearly left an impression.

"Ellington insisted that every drummer who was in the band thereafter played a double bass-drum set like Louie"

“Ellington subsequently insisted that every drummer who was in the band thereafter played a double bass-drum set like Louie, so you’ve got Rufus Jones, Dave Black, Rocky White, Sam Woodyard,” says Pete. “One of the most important and visible big band drummers of later years in the US was Ed Shaughnessy on The Johnny Carson Show with his two bass drum Ludwig set, but it didn’t really become part of the everyday vocabulary of what big band drummers do.

"Probably a lot of it was to do with logistics as much as anything. When you’re cramming a band onto a bus and zig-zagging across America 40 weeks of the year, a second bass drum might be considered a luxury or even a burden.

"It’s sometimes the practical issues that end up determining trends in drum equipment. Somebody asked Elvin Jones why he started using an 18" bass drum, he said because it went in the boot of the car. That was it.

"A quartet could travel around, the bass on the roof rack, the drumset in the boot and four guys in the car. It wasn’t because it sounded a particular way or it was a jazz thing to do. It was just a practical solution to travelling around economically.”

Small is beautiful

While drummers of the swing era are best known for their exploits in big bands, they were equally adept in small groups.

Krupa played in trios and quartets both with Goodman and as a bandleader in his own right; Louie Bellson recorded in a sextet with Count Basie, while Jo Jones played in small groups with Art Tatum, Lester Young, Teddy Wilson and many others during the ’50s.

Versatility is key

“There is a common misunderstanding that big band drummers can’t play in small groups and small group drummers can’t play in big bands,” says Pete, “but what you have to consider is that once you play the first chorus of a chart and somebody stands up to blow a solo over the changes, then a big band has suddenly become a quartet. Maybe on the second chorus of the solo there might be sax or trombone backings, so then it becomes an eight-piece.

"There is a common misunderstanding that big band drummers can’t play in small groups and small group drummers can’t play in big bands"

"This is why big band playing is such a total experience for a drummer because the ensemble size changes all the time and you have to reflect that in how you accompany the band, where you’re at dynamically.

"With so much contemporary writing out there now, you might start off with a swing chart and then you might play a samba or some funk, a shuffle or a calypso. There are big band versions of so many different genres.

"Particularly for young drummers starting out, it’s a fabulous way of really learning a lot about playing the instrument because of the huge range of demands placed upon you by the sheer diversity of style that a modern big band library of music is likely to contain.”

Keep on swinging

The Swing Era wound down in the mid-1940s, when many musicians were called up for World War II, rising petrol prices made it economically unviable for large groups to tour, and bebop became the dominant force in jazz, encouraging audiences to sit down and listen to the music instead of dancing. Yet the genre never followed the dodo into extinction.

Buddy Rich defied the odds to continue leading a big band into the 1970s, and swing remained a vital part of every jazz drummer’s repertoire.

The essence of cool

“In the ’50s the emergence of Sonny Payne in big band music and of Joe Morello in small group jazz, those guys really made Buddy Rich and his contemporaries look to their laurels,” says Pete.

“Sonny Payne was a fabulous player. Unfortunately all too often remembered for the showboating, the stick juggling and all the crazy tricks, which sometimes can blur the focus of what a really superb big band drummer he was.”

"You can hear that Morello is every inch a big band drummer"

As for Morello, the essence of cool jazz drumming with the Dave Brubeck Quartet, “You can hear that he’s every inch a big band drummer,” says Pete.

“He took a lot of that driving, swinging essence that is such a part of big band playing with him into the Brubeck situation but just did it very, very quietly.”

Swing into the future

While the original swing giants have all joined the great big band in the sky, swing music has found an unlikely champion in Robbie Williams.

British session ace Ralph Salmins contributed to both of Robbie’s big band albums – Swing When You’re Winning in 2001 and 2013’s Swings Both Ways.

Asked what modern producers look for in a swing drummer, Ralph replies, “They are looking for a modern spin on it because recordings nowadays are much more punchy than they used to be, so everybody is playing stronger. Really what you’ve got to do is you have to take from traditional drumming and then adapt that to a more modern setting. I don’t sound like old school drummers, not with something like Robbie.

Punchy

"I take someone like Sonny Payne as an influence and I try to swing the band with a nod to old fashioned-sounding drums, probably no muffling on the toms, make my drums sound like a jazz set, and that helps. But I play quite punchy for most of the modern stuff.”

One of the key differences in recording techniques is that nowadays the drums are typically in an isolation booth, whereas in the ’30s and ’40s they would have been out with the orchestra which meant the player had to be very aware of their own dynamics.

“An isolation booth means that you can play a lot louder without it spilling on to the other mics, but that’s not necessarily an advantage,” says Ralph. “In the old days, the dynamics of the drummer were much more a part of it. Obviously drummers had to keep quiet when there were quiet things going on. Because of amplification and iso-booths that’s not so much the case now.

"I try to play with as much dynamics as I can so if there is a piano solo I try to play quietly to make a difference. It brings the music to life, otherwise there is a temptation to just play loudly all the time and that’s boring.

"If you’re in the same room as the band, you have to really think carefully"

"If you’re in the same room as the band, and I’ve done a few recordings like that, you have to really think carefully. When you play one loud snare beat it really has an impact. The old recordings were like that.

"The reason all the Basie drummers played on the hi-hats for Basie’s piano solos was for balance. I try to get that message over to people as strongly as I can. The more you know the music, the more you realise balancing is where it’s at.”

When Ralph answered a last-minute call to play with the Count Basie band at the Barbican in London in the early 1990s, he realised just how important dynamics canbe as the band doesn’t use any monitoring on stage. “They just play acoustically,” he says. “The PA goes out front, but when the piano plays it’s not miked up.

"If you don’t play quietly, you just don’t hear it. It’s a different way of playing and it’s lovely.

They balance just like the old school. If you look at the great modern players like Jeff Hamilton and Peter Erskine, they play with fantastic dynamics and they balance beautifully with the band.”

MusicRadar is the number one website for music-makers of all kinds, be they guitarists, drummers, keyboard players, DJs or producers...

- GEAR: We help musicians find the best gear with top-ranking gear round-ups and high-quality, authoritative reviews by a wide team of highly experienced experts.

- TIPS: We also provide tuition, from bite-sized tips to advanced work-outs and guidance from recognised musicians and stars.

- STARS: We talk to musicians and stars about their creative processes, and the nuts and bolts of their gear and technique. We give fans an insight into the craft of music-making that no other music website can.