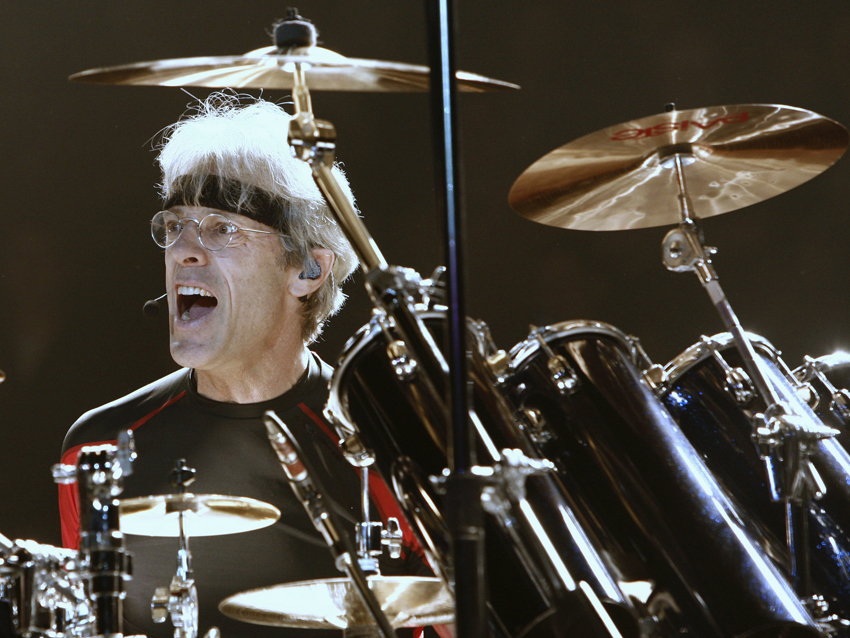

Stewart Copeland picks 16 fun drum albums

“As a kid, I only listened to albums for the drums," says legendary sticksman Stewart Copeland. "I never paid attention to the vocals. I was really into guitar and bass, though. But growing up, it was really all about the drums. In fact, we can take that up till yesterday – or tomorrow."

Asked by MusicRadar to compile his list of 10 essential drum albums, Copeland immediately expanded the concept to 16 records but also took exception with the notion of the word 'essential.' "That takes all of the fun out of it," he says. "In fact, to me, this should be just that – fun drum albums. These are all the bad influences, albums that drummers, if they want to make a living out of playing the drums, shouldn’t listen to."

He then quickly points out the obvious: "Of course, I’ve listened to them, so somehow I managed to escape unscathed."

In Copeland's view, slavish devotion to copying and emulation is the death of musical creativity. "When I was in college," he says, "there would be the guy who would break out a guitar and play Working Class Hero, and all the chicks thought he was great. Then I’d pull out a guitar and start twangin’, and they’d look at me funny and say, ‘But I don’t know that song.’ And I’d say, ‘Well, of course you don’t – I wrote it.’ That whole thing of replicating what others do is a siren call. The sirens lure you to the rocks of unoriginality."

What follows on these pages are Copeland's picks for, as he calls it, "the bad medicine for drummers, the fun stuff." But he adds the following bit of caution: "Fun can also be bad for you. So many seminal musicians did a lot of damage. Jimi Hendrix with the wah-wah pedal – ahhh, fantastic! But his progeny are heinous. Those practitioners of the wah-wah pedal who are not Jimi Hendrix fuck it all up.”

In other words, listen, learn and have a blast, but don't let those sirens draw you in, no matter how beautiful they may appear.

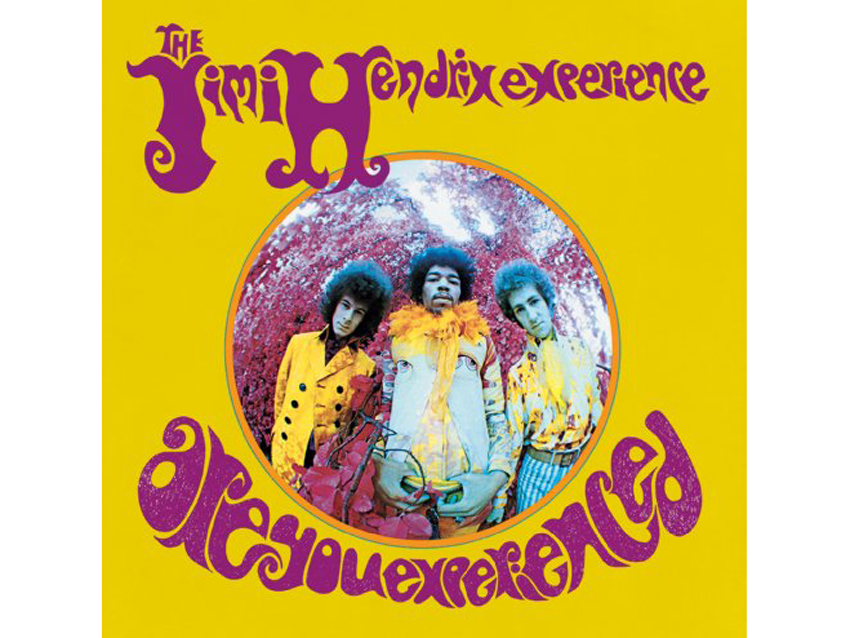

The Jimi Hendrix Experience - Are You Experienced (1967)

“Mitch Mitchell was the excitement behind the guitar. The guitar and the drums were perfectly matched and mutually supportive. For me, that was the essence of a rock band, that interplay.

“Mitch had all kinds of chops that were light and sophisticated inside some extremely heavy music. That made a big impression on me, the idea that you didn’t have to be thunderous to make an impact.

“I used to go down to the Henritt’s Drum Store in London and daydream that Jimi and the boys would walk in as I was checking out a snare drum. They’d hear me playing and go, ‘Hey, kid – you’re good!’ [Laughs] Then we would go back to their place and jam and jam and jam; and Mitch and I would become best friends…

“Years later, I was talking to Henritt, who told me that producers used to come in all the time and say, ‘Hey, you got any kids in here who can play drums?’ So that actually used to happen – not to me, though.”

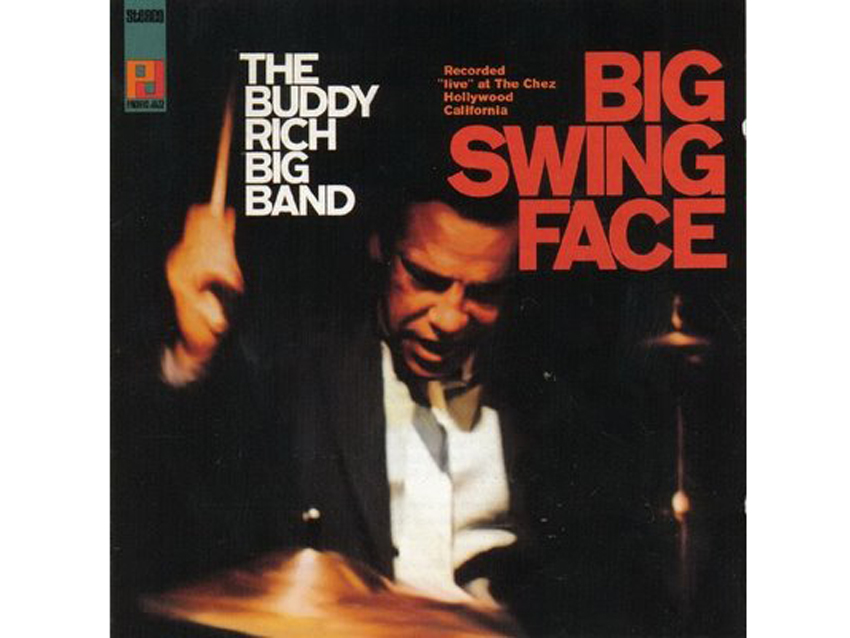

The Buddy Rich Big Band - Big Swing Face (1967)

“Buddy was the Mozart of the drums. I would say that he and Joey Jordison, of all people, have taken the technique – the finesse, the detail – to the highest level. And in both cases, they do so without killing the band.

“When you listened to Buddy, you realized that you had to do a lot more fills. But he rocked the band. The arrangements were important to him. And he [the arranger] was the guy Buddy shouted at on the bus.”

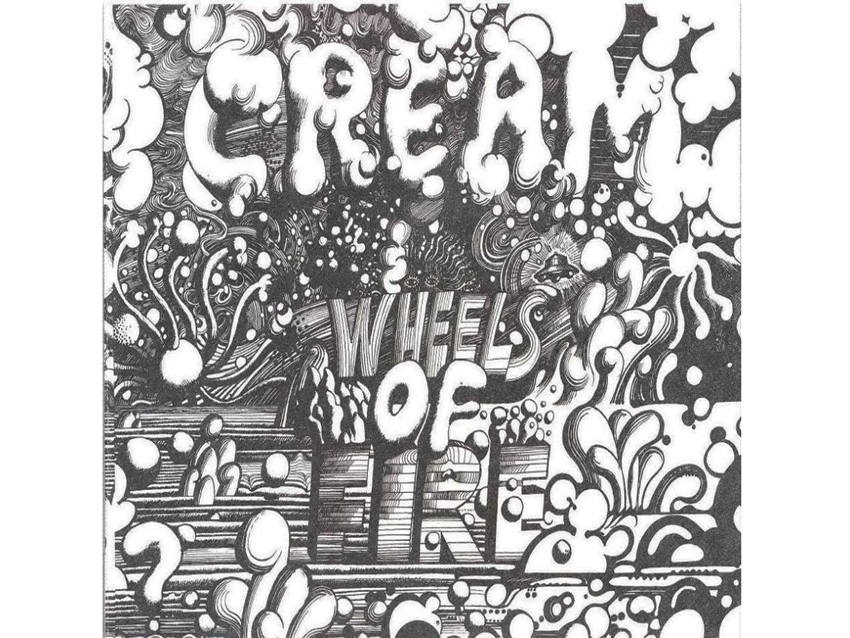

Cream - Wheels Of Fire (1968)

“The drums are very thumpy. Ginger Baker has a sound that hasn’t been replicated. He was so unique and had such a distinctive personality. Nobody else followed in his footsteps. Everybody tried to be John Bonham and copy his licks, but it’s rare that you hear anybody doing the Ginger Baker thing.

“Fortunately, Ginger’s real personality cannot be replicated. He’s actually a great guy – we get along just fine. We have polo in common. He calls me ‘young man.’ He can call me any damn thing he wants, as long as he doesn’t hit me with his cane.”

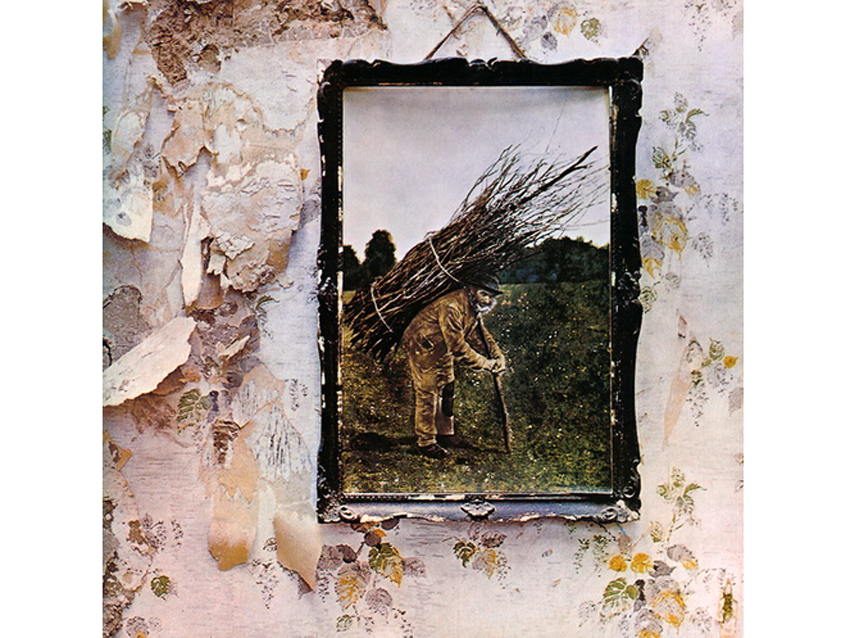

Led Zeppelin - Led Zeppelin IV (1971)

“The first albums are great, of course, but I didn’t pick up on them at the time. On IV, the economy and weight of John Bonham’s drumming are what really stand out. He managed to be powerful without Billy Cobham-style or Joey Jordison-style drum fills.

“Plus, there’s a funk groove, which was an instinctive thing with him. [Sings a musical phrase to Black Dog.] ‘Ba-dum-bahh-dum, ba-dum-bahhh-dum!’ That’s the one. Economy and power – and he got his power from the economy.”

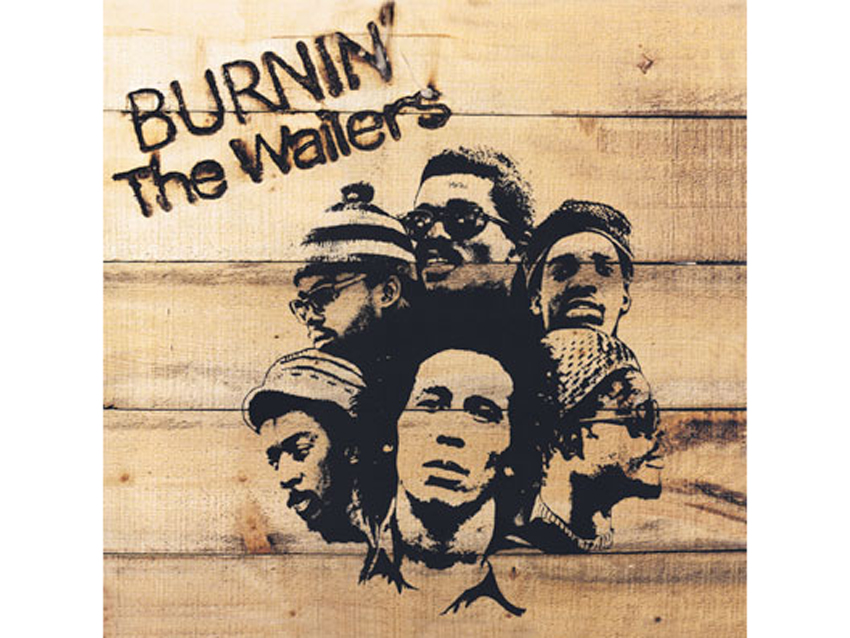

The Wailers - Burnin' (1973)

“You could pick any Wailers album, but this is the first one that got me fired up. Burnin’ is the big one. I would also have to mention a co-album in this slot, and that’s Burning Spear Live.

“That’s the whole reggae thing, really, where the concept of reggae traps drums turns the patterns upside-down and backwards. That’s extremely influential in my particular case, but I think all over everybody was very affected by the music of these two albums.”

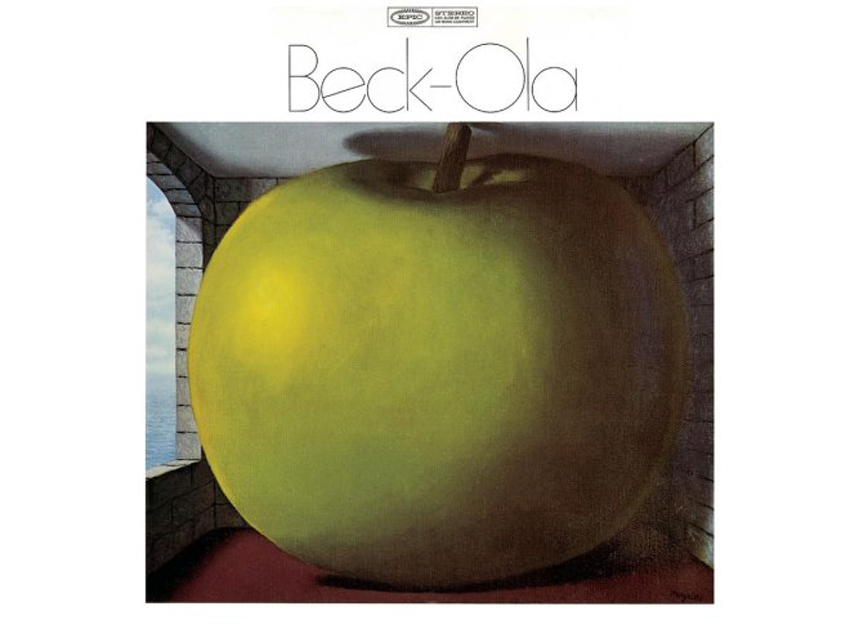

The Jeff Beck Group - Beck-Ola (1969)

“I can’t even remember the drummer’s name [Tony Newman; Micky Waller plays on Sweet Little Angel], but this is a case of a guy who was never heard from again, but he just plain rocked, as did the bass player, too.

Spanish Boots is one of the great rock tracks of all time. And old young Rod Stewart, that was the best he ever was, when he was an unknown singer in somebody else’s band.

“I discovered the album back in the day. The synergy of the guitar and drums stood out. As a kid, I was a frustrated guitarist and bass player – still am – and I could easily have taken a left or right turn and been either of those two things. I ended up playing drums instead. Bass and guitar have always been very important, and on Spanish Boots – and the whole album – those elements really come together.”

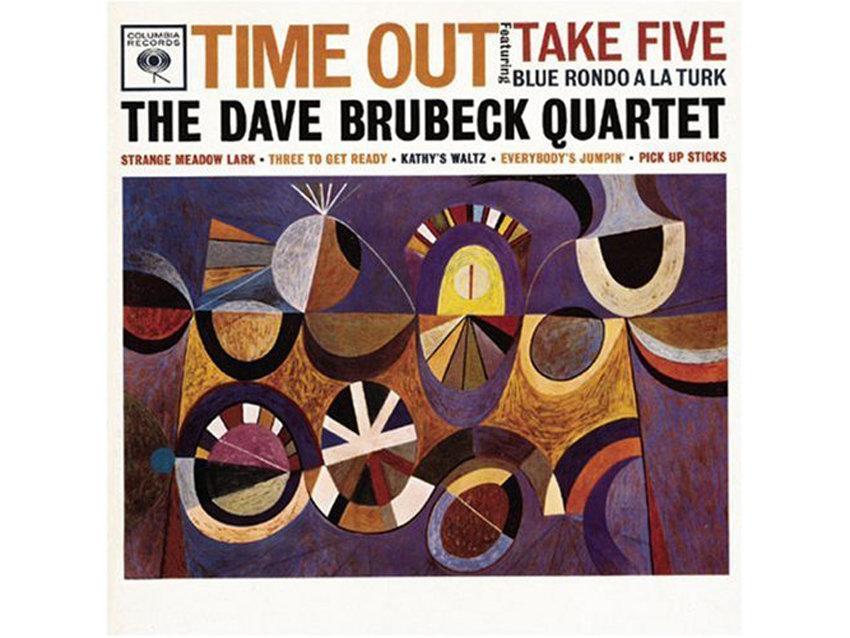

The Dave Brubeck Quartet - Time Out (1959)

“Blue Rondo A La Turk and Take Five – those are the tracks. That’s good medicine. This is the fun list, but those are both fun and good medicine, so you get the whole package.

“Once again, it’s very Bonham-esque, the economical power, where you listen to the drums breathe. Hearing this made me listen to the sound of the tom-toms and the resonance of the drums. It reminded me to, every once in a while, leave some space so that you can hear the individual voice of the drum, which can be very beautiful.

“That’s what that drum solo [Take Five, performed by Joe Morello] is all about, the sound of those drums.”

Mahavishnu Orchestra - The Inner Mounting Flame (1971)

“Both the first Mahavishnu Orchestra album and the second [Birds Of Fire, 1973] are pretty important. I had burned out on jazz because I had been raised on it, so when I heard this music, I was pumped.

“I was the only kid on my block who could play the opening cut of the Mahavishnu Orchestra album. I’ve followed Billy Cobham’s playing. His first solo album had a really big track with a simple bassline. Whenever I’m writing a bassline, I have to remind myself, ‘No, no, no, no!’

“But those chops… that’s bad medicine. Not good for you children. Avoid.”

Return To Forever - Romantic Warrior (1976)

“This album, like the Mahavishu records, came out at a time when other musicians would holler, ‘You gotta hear this!’ That’s how it happened in those days. For me, Mahavishnu and Return To Forever kind of folded together a bit.

“I put this album right up there with Mahavishnu Orchestra. Lenny White on the drums was just as important as Billy Cobham. He wasn’t as techno-flash as Billy, but he could really give those lame jazz chords a kick up the ass.”

Slipknot - Slipknot (1999)

“Too many drums, but it works. All that cool shit that he does with both his feet and his hands has to be marveled at. I mean, with his feet he does what most drummers aspire to do with their hands. And then the stuff he does with his hands – look out! Genius.

“I went to a heavy metal festival to see another band, Sepultura, my buddies from Brazil, and everybody backstage was saying, ‘You gotta see Slipknot. You gotta see Slipknot.’ So I went up on the stage to watch them, and when they came out of their trailer it was like, ‘Ho-ly shit! What is that?’

“The stage manager looked at me and touched his ears, which I guess was his way of telling me to cover my ears. Just as I did so – bang! The explosion of the volume on stage, and that little fucking bastard on the drums [laughs]. Goddammit, you can’t do that!

“I had no idea that he’d be that good. I was aware that in heavy metal, you have to be of the highest grade to play that stuff – you can’t play that way in the blues. You can get away with it in jazz, but most drummers can’t do what Joey does.”

The Doors - Strange Days (1967)

“John Densmore – another jazz guy playing in a rock band. A very light touch, but it works. The drumming in jazz is great, but it’s those lame jazz chords that fuck it up. So you put those guys with a rock band, and it sounds terrific. That’s the right mix.

“Mind you, Buddy Rich, on his later albums, attempted to do pop music, and he brought in a guitarist with a wah-wah pedal. That pretty much killed that! [Laughs]

“I talk about John Densmore all the time. He had an individual, unique style that I couldn’t replicate, this kind of trance-like groove that was such a really a big part of the trip of The Doors.”

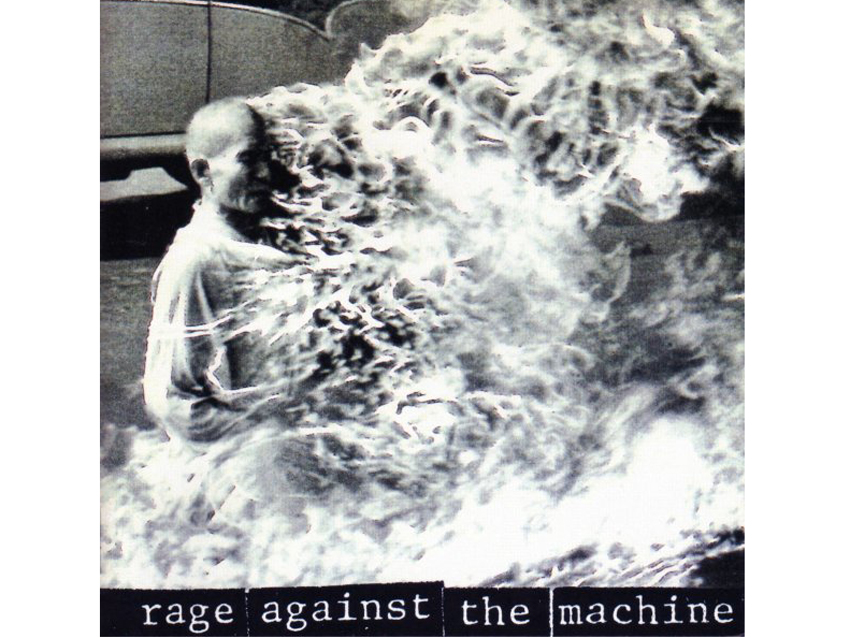

Rage Against The Machine - Rage Against The Machine (1992)

“That would be Brad Wilk, who is sort of like the John Bonham of his generation. He has that same sense of tasteful economy, so he might wind up on the helpful list.

“He’s a vitamin, but he’s also the bad kid in class. You could earn a living playing like him. Once again, it’s the synergy. Tom Morello rules, of course, but I’m listening to [bassist] Tim [Commerford] and Brad. Those two guys, now that’s a rhythm section. Zach can do whatever the fuck he wants – he can sing, he can shout, he can chop his head off – but that rhythm section makes whatever he does sound way cool.”

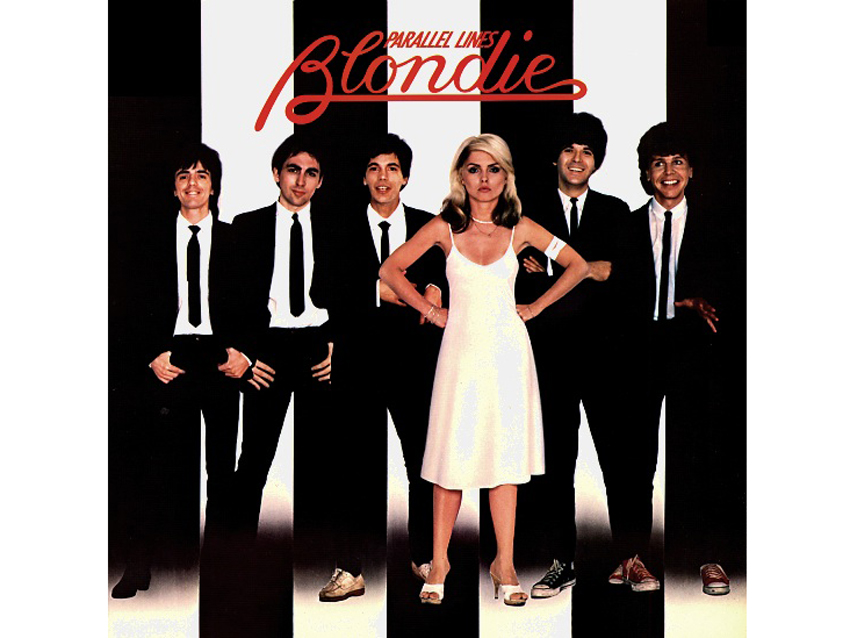

Blondie - Parallel Lines (1978)

“Now we’re getting into the good medicine. This is the album where it all came together. Clem Burke has chops, but he doesn’t kill the band.

“He has a kind of kinetic energy, a sparkle, an effervescence that lifted up that girl-pop band dominated by an imagey girl, and he made it serious. It got played in discos a lot, but it wasn’t disco, and Clem didn’t play disco style. He played old-school pop style but made it sparkle.”

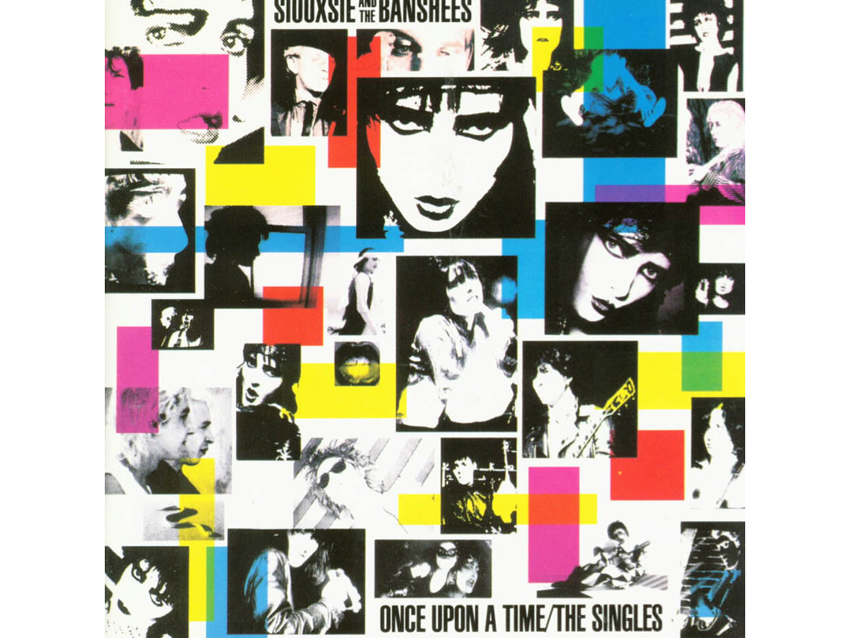

Siouxsie And The Banshees - Once Upon A Time: The Singles (1981)

“I think that Budgie was the second drummer in the band. One side of this first greatest hits album is all him. You know that kind of new wave quasi-punk but sort of fashion-punk era? Siouxsie was all about that, but Budgie made it really powerful.

“Very economical and offbeat, too. Budgie didn’t play your standard hi-hat-kick-snare; there were a lot of tom-toms and a big throb.”

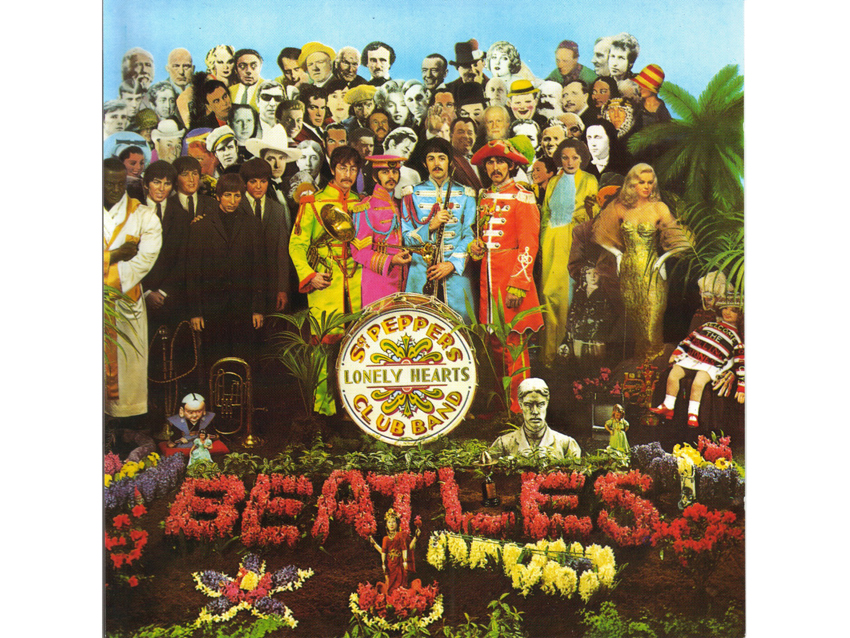

The Beatles - Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967)

“Fuck it – let’s pick this one. Why not set the controls for the heart of the sun? Ringo plays all of this creative stuff. There’s all of this backtalk: ‘Was Ringo the greatest drummer in the world?’ ‘No, he wasn’t even the greatest drummer in The Beatles.’ For a start, Paul McCartney never said that, I’m sure. George Martin never said that, I’m sure. John might have that kind of thing, but it just wasn’t true.

“We know what Paul sounded like. On those couple of things where he played drums, he’s really pretty good. But people who aren’t drummers often play drums better than drummers because they do all of the stuff you aren’t supposed to do, and that can be interesting.

“All of that notwithstanding, it’s not up to Ringo’s standard by any stroke of imagination. Ringo played really solid parts that were imaginative. You can hear them, too; they’re not just backbeats behind the singers. There’s big drum moments that are all about big tom-tom sounds, big drum fills and odd rhythms that aren’t normal.

“Each Beatles track has something unique, a trick or something cool built into it. In many cases, it’s the drum thing.”

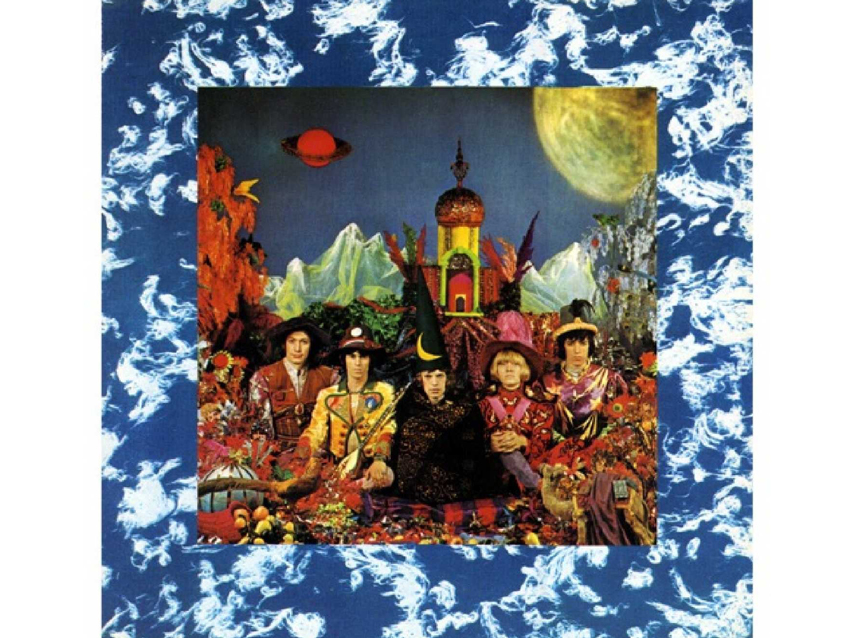

The Rolling Stones - Their Satanic Majesties Request (1967)

“Contrast Ringo with Charlie Watts. Charlie’s laid-back feel is just the perfect thing for Keith Richards’ fucked-up guitar. And that wasn’t so much about creativity as it was about feel and groove, this inescapable shuffle rhythm that makes you want to do wrong stuff.

“This album is their bomb, but it’s my favorite. It was their pathetic response to Sgt. Pepper, but it was still a fucking great album. It reeks of ‘me-too-ism,’ yet it’s still a fantastic record. I probably listened to it more than Sgt. Pepper. It’s darker and meaner, and I was a dark, mean kid. I was hostile and angry, and I listened to music that expressed my rage.

“Charlie’s technique is very idiosyncratic. There’s all kinds of bad technique going on with him, but he grooved. He had that famous thing where he never hit the hi-hat and the snare at the same time. Every backbeat, there’s a hole on the hi-hat pattern.”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

"At first the tension was unbelievable. Johnny was really cold, Dee Dee was OK but Joey was a sweetheart": The story of the Ramones' recording of Baby I Love You

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track

"At first the tension was unbelievable. Johnny was really cold, Dee Dee was OK but Joey was a sweetheart": The story of the Ramones' recording of Baby I Love You

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track