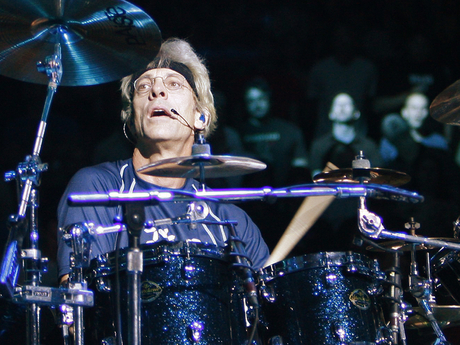

"I'm an ecstasy player," says Stewart Copeland. "I'm an exuberant, leaping forth explosion." © Brendan McDermid/Reuters/Corbis

Polo player, author, documentary filmmaker, movie score composer, photographer - by any measure, it's safe to say that Stewart Copeland leads a full life. Oh, we almost forgot - for much of his time on this planet, Copeland has also been the drummer for a spunky little rock 'n' roll combo you might have heard of, The Police.

"When I sit at the drums, I just do what I do," Copeland says. "That's something that's never changed. I've never been very good at being a session player. When I get on the drums, it's a primal scream. Fortunately, I've been able to find outlets where where that approach not only works but has been encouraged."

Recently, MusicRadar presented Part 1 of our interview with Copeland, a wide-ranging conversation in which the erudite and witty drummer held forth on topics such as The Police, drum solos, Rush (he's friends with Neil Peart but doesn't listen to the band's music) and how he's incorprated double bass pedals into his playing.

In this, the conclusion of our interview, Copeland talks about the recording of several Police classics, how he dove headfirst into composing film scores, his quirks as a drummer and why he remains a Tama man after 30 years.

What would you say are the biggest musical lessons you learned from both Sting and Andy Summers?

"Hmm… so many. So many lessons. Things that we learned together. Things we taught each other. Co-dependence is one of the main things we agreed on as a primary ethos - that we are not 'a guy,' but rather we are three guys, and that we are each other. I am whatever Andy is doing on the guitar. That's me.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

"There was a band saying: 'I am nothing. I am no one.' And we had the ring of good vibes that we would don in moments of high tension. The ring of good vibes was a thing that they had on the two-inch reels that would hold the tape in place. When you pull the two-inch reel off the deck and you're just about to put it in its box, you first wrap this thing around it - it's like a loop which joins with Velcro to hold the tape onto the reel - and then you put the whole thing in the box.

"That loop we would put around our heads - it was the ring of good vibes - and we would remind ourselves, 'I am nothing. I am no one.'"

Conversely, what do you feel you might have taught them?

"To hire a quieter drummer!" [laughs]

You know, Message In A Bottle is one of those songs that drummers have such a hard time nailing. There's videos on YouTube, and people get close, but nobody ever gets it quite right -

"Well, that's because there's overdubs. There's a ride cymbal bell on the backbeat. And I might have added some toms, but I later ended up playing them as part of the part. The main thing is the ride overdub that I've seen drummers in lounge bands attempt to play with whatever else is going on. The things that you can do in the studio to tart it up can only do just that - decorate it a little bit. But when you're actually playing it live, you don't need all that help."

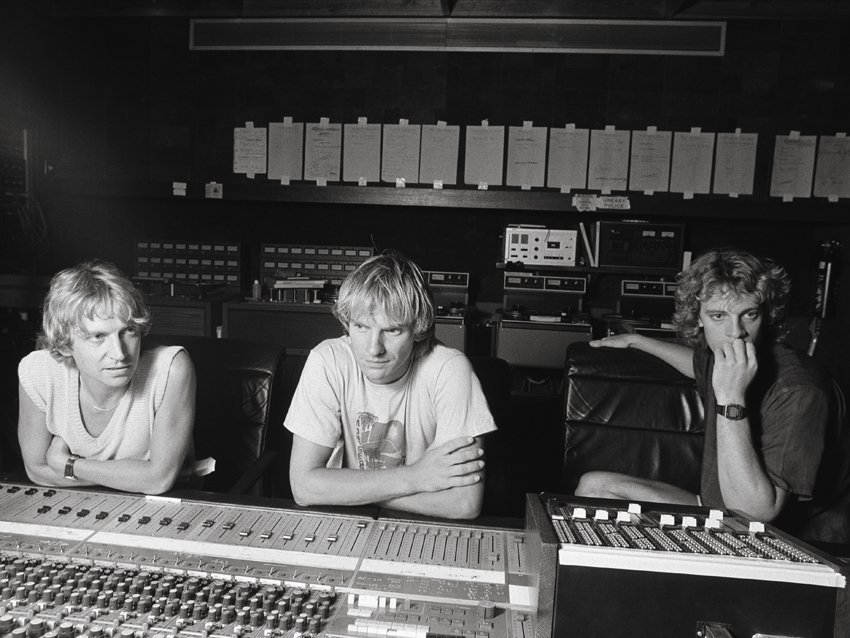

To 'Police-ify' or not? Andy Summers, Sting and Copeland contemplate in Montserrat, 1981. © Lynn Goldsmith/Corbis

What was the hardest Police track for you to nail on the drums? And do you still hear that song and think you didn't get it quite right?

"Well, the last part of that question I could apply to any song, because we would go out on tour and play the song every night, and it would get honed and honed and honed, and then we'd think, Shoot, that's what we should have done on the record. In fact, if you listen to a record mid-touring, you think, Gee, that's so unpolished; I can play that now with such confidence and slickness. It sounds like we were just making it up on the day. Which we were - we all were.

"Many of the tracks went very easily. Murder By Numbers, the version that's on the record, is the very first time we ran it down. Sting and Andy were sitting at the dinner table in Montserrat, Andy starts playing the guitar and Sting says, 'Hang on, I've got a lyric for that.' He pulls out his book, and while the two sat there over dessert, figuring out how to put the lyrics to the chords, I'm sitting there thinking about what to do with it. Then they said, 'OK, let's put that down.' They went down to the studio - my drums were in the dining room - and I started up the rhythm while they played the song. That performance is what's on the record.

"On the other hand, Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic was a long war, a battle, and we ended up right at the beginning. The problem was, Sting had a demo of the song that was a hit. You could put it on the radio just as it was, and it would have been a huge hit. It had all the elements. But we wanted to 'Police-ify' it because we're a band. And it was all done on keyboards, but of course, we're a guitar band. Sting did it on a drum box, and I'm not a drum box.

"We tried it as reggae, we tried it slower, we tried it as punk, we tried it every which way, to the extent that it veered away from the original demo and didn't sound like a hit anymore. Finally, it was like, 'Screw it. Just run the thing down. Sting, you flag me through the changes, and let's just do it.' That was the first thing in the day. That take you hear on the record are the drums overdubbed to Sting's demo, with Sting standing over me waving me through it.

"A lot of it is unexpected because I didn't know what I was doing. But it had what we needed to build the track back up. We had the drums, and then Andy started working on the guitar with just the drums, and then Sting redid his bass to my drums instead of the drum box. We built it all up from there."

It's interesting to now hear you describe the recording - the song does have an urgency.

"The amazing thing is that it didn't drift out. There's a syndrome of playing to a click track, and it's something I can hear instantly if somebody is doing that: You do a fill, and you speed up just a hair, and then you hesitate just a second because you're waiting to hear that click catch up to you. I can hear that. Even in my own playing, when I'm playing to a click, I hear it - it drives me nuts. I go through all kind of Pro Tools hassles to cure those parts."

Let's talk about your work on movie scores. Before you scored your first film, what was your level of study? Did you listen to the classic composers or anything like that?

"No. None whatever. No level of study. Complete music punter."

So, when you first talked to Francis Ford Coppola about Rumble Fish, did you have any idea what you wanted to do?

"Well, he probably did - I didn't. I had no idea about movie scores, and he was calling me up, and I thought we were going to make music together and he was going to shoot some kind of movie about it. I had no idea about the role that music played in movies, and I had a completely outrageous, laughable idea about what I was getting myself into when I started on that. But I learned." [laughs]

What was your process to scoring Rumble Fish? That was back when people were still looking at footage on Moviolas, right?

"Yes, absolutely. You make that sound like before electricity, and it almost was… before computers. What I did was, I read the script, and I attended some of the rehearsals in Tulsa, Oklahoma. It was all about concept. He had this concept: 'Time is ticking. I want it to be like High Noon. You're relentlessly moving towards this showdown. The clock is ticking…' With this concept, without knowing how to score actual scenes with actual dialogue, I was like, 'Cool. Time, rhythm, breaking down rhythm.'

"So while they were rehearsing, I recorded a bunch of industrial sounds. I found stuff in libraries and started making loops - literally, physical two-inch loops. It was all concept, and Francis is very much into concept. His philosophy, in working with everybody you have to work with to make a movie, is to find the right guys and turn them loose - as opposed to another directorial style, which is to micromanage every frame, every sound bite. Francis is the former.

"With Francis, he comes in and checks on you occasionally, and says, 'Yep, great.' And presumably, if it's not 'Yep, great,' it's 'Nope, you're gone.' I never got that. All I got was the bear hug. It was a wonderful thing."

How about Oliver Stone? What was he like to work with?

"Funny you should mention that 'other' form of directorial approach. [laughs] He's a man of detail. He loves his details, and he loves every aspect of everything working together, and he needs to know how and why they're working together.

"For instance, on Wall Street, all of the stock trading information that was flashing on the screens behind the actors had to be real stock information. With the music, he wanted to know the exact emotional message of every note."

How did you go about explaining that to him?

"Well, I just had to think of the exact emotional message of every note."

But I would assume that sometimes you were just being spontaneous… or waiting for inspiration.

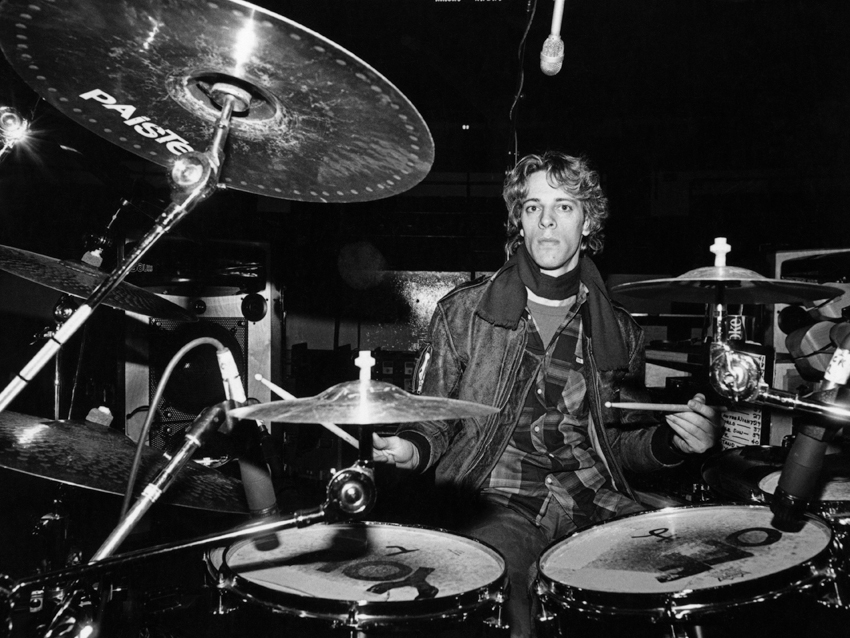

"Well, I don't wait for inspiration; I sit down and turn it on. That sounds a little facetious… or facile… but when you make your living from creativity, you just know when you sit down in the morning in front of your equipment that you're going to produce it. It might not be your best work, or it might be your best work, but you're going to produce something because that's what you do at 10 o'clock in the morning.

"That's how creativity works for me. It's not so much waiting for inspiration as it is addressing the problem: I need to write an opera. What's it about? OK, that seems like a pretty wide-open place to start. In fact, I have that question before me today even as we speak. The funny thing is, once I solve that question - 'What's it about?', 'It's about… World War III' - then I have something to work with. And that's good, that's something tangible. But then that's bad, because now it's not a love story about a Medieval knight with soiled underpants. It's not a nature movie. There's 50 million things it isn't.

"Every decision you make is a step forward, but a lot of doors close. Still, it's a mission. Where do you find the creativity? You sit down, you face the problem. The problem can be as broad as 'What's this movie about?' It can be as finite as 'How can I get from bar 360 beat 4 to bar 361 beat 1. It's a mission."

How do you go about working on soundtracks these days? What kind of gear setup -

"Well, I don't do soundtracks these days. I haven't taken a call from my agent in about three years."

Oh... Well, he's probably hoping you pick up the phone.

[laughs] "Yeah, really."

But what is your setup? I imagine it's a lot more streamlined than it used to be.

"Oh, very much so. All the places where I used to put yards and yards of mixing consoles are now flat surfaces where I can put pizza. [laughs] But I do like to work on Digital Performer, on Final Cut, on Photoshop, on After Effects, on Sibelius and Finale. Let's see… I use Pro Tools, of course. And lot of other little ancillary plug-ins and applications.

"But you know, it gets confusing. All of these different applications - where's 'play'? Or how do I advance just one frame? It's different on each application. It's like switching languages. But I find it endlessly engrossing. It amazes me that I can walk in the studio every day, usually at eight o'clock, and I just can't wait to open up my applications and start playing with shit."

Your involvement with Tama Drums goes back a long way. You were their first endorser, right?

"I might have been first - I don't know. Billy Cobham was pretty early. Quite a while ago, here's an anecdote: There I am at the NAMM Show, which I do every few years to pay my dues, and I'm at the Tama booth where they're giving out plaques. 'And we have so-and-so, been playing Tama for five years…' Clap-clap-clap. 'So-and-so, been playing Tama for 12 years…' Clap-clap-clap. And finally, it's 'Stewart Copeland, been playing Tama for 30 years!'"

That's got to make you feel, what… old?

"Well, the other day, a young player came over to my studio, and he saw a Stratocaster on the wall. 'Wow, man, that's a '78! My God, that's really cool! Where'd you get it?' And I was like, 'I bought it new at Manny's.' That's how old I am. Actually, I'm in my 60th year and stronger than ever. It does occasionally blow my mind, how long I've been on the planet."

What was it about Tama that first appealed to you?

Two things: Just looking at them, they had these huge, robust stands. The Ludwig stands and the others - Rogers, Premier, Gretsch - all the stands that prevailed at the time were just inadequate for aggressive playing. The Tama stands, you could climb around on them; they were like monkey bars. So that's what I noticed when I looked at the drums.

"When I started playing them, I was like, 'Wow! These are really rich.' They were powerful, sure, but mainly they were better - a thicker, fatter, cooler sound. At the time, I was playing my first record company-purchased kit, a giant Ludwig Perspex monster. It filled my heart with joy to own such a thing, so much so that I didn't even notice that it sounded like crap. And so, these 9-ply wooden drums from Tama, my ears just went, 'Whoa! That's incredible.'"

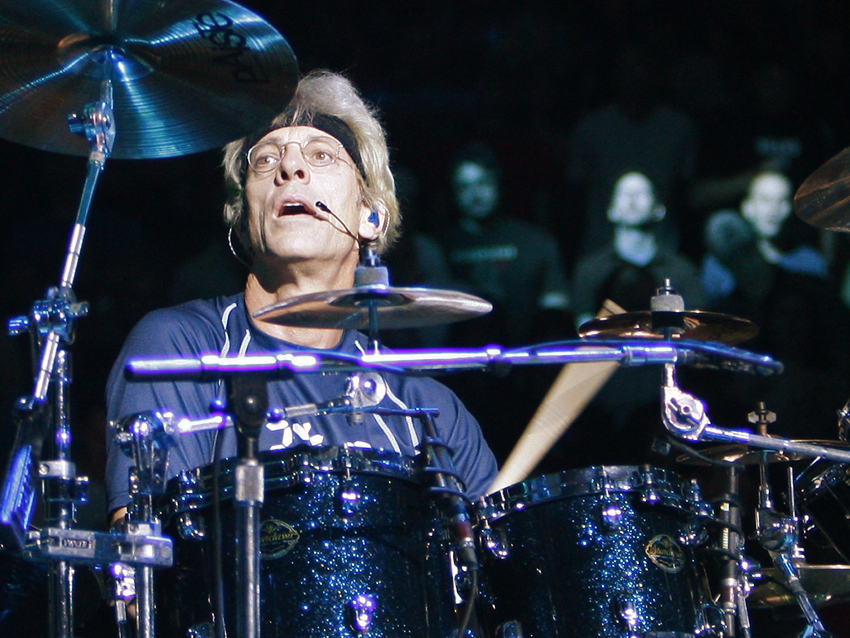

Copeland with his spiffy Tama signature drum set, 2007. © Sara De Boer/Retna Ltd./Corbis

"I came in contact with these drums when I was writing product reviews for Sounds magazine. I was given this kit and set them up at a Curved Air soundcheck, and at the same time I made this discovery and had the epiphany, the soundman came running up going, 'Whoa, whoa, whoa! What are those? Play those!' He pleaded with me to use the Tama set instead of my big Ludwig kit. Which I didn't… at the time.

"You know, people always ask me how I got the idea to tune the drums up high. I think it came from the Tama drums, because the higher you tune a drum, the more response you get, the better the bounce, the easier it is to play, the more live the drum is and all that. But in most cases, they just go 'ping' if you tune them too much; they lose the sound. But with Tama drums, I could tune them so they had incredible bounce on the skins because of the tightness, but they sounded better and better the higher I pitched them."

All drummers have their quirks - the height of their thrones, the angle of their toms, even what kinds of shoes they wear. What are your idiosyncrasies?

"Well, I think these quirks develop with technique. If I play baseball, I'll notice the difference between one bat and another. But if I were a professional baseball player, I'll notice the finest, tiniest, most minute deviation from the perfect bat. And so it is with instruments. With drums, because I've been playing them for so long, I'm probably much more, uh, 'foibled' than I should be.

"But I've always followed the rule of sticking to the standard: having my drums set up the way everybody else does, so that when I sneak in and try to steal their gig, I can play their drum set comfortably. That's why I don't have my drums set up left-handed, so I can jump on any right-handed kit and steal somebody else's job.

"Same with the positions of the kit - very standard. With sticks, I have my own design of stick, which is [Vater] The Standard. It's not a big fat heavy stick, it's not a pencil, it's right there in the sweet spot of the middle.

"As for foibles, I need a shower after the show. I'm extremely sweaty after playing, but it's not just that, it's the endorphin rush combined with the shower endorphin rush makes it too ecstatic an experience to forego. And I do have to dress light when I play. I'd love to wear a cape and a hat, plumes and epaulets, but no… can't do it. I'm envious of singers and guitarists who can wear outrageous costumes, but I can't."

"I don't wait for inspiration," says Copeland (pictured here in 1983). "I sit down and turn it on." © Lynn Goldsmith/Corbis

Some years back, you played with The Doors briefly - you almost did a proper tour with them. Why did that fall apart?

"Well, I had an injury, but that came on top of it really being a mismatch. I was the wrong guy for the job, period. I was in there because I was such a fan of the band. Robby's guitar, Ray's keyboards - man, that's the sound of The Doors! You know, you're just waiting for Jim to come in… and he doesn't. But then the guy that they found [Ian Astbury], it was real close. I was in those rehearsals and it was pretty magical. But when I would go off into the ecstasy of the moment, my instincts for what I do just turned it into something else.

"Doors music - and I didn't realize this as a fan, but I did when I attempted to play Doors music - is really about trance. The way John Densmore got into that groove and just stayed there, and he did all kinds of really cool, persnickety stuff, it was in the trance. And I'm not a trance player. I'm an ecstasy player. I'm an exuberant, leaping forth explosion."

So far, you've had a pretty full schedule in 2012. You're playing with Stanley Clarke, you've conducted a residency at the Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas...

"I still like doing it. But one thing I do want to mention - my YouTube site. It's a punter's channel. I haven't really gone into marketing it, which is probably why it's still under the radar. My studio is like a giant train set that I love to tinker with, and when Final Cut is rendering interminably, I'm crawling around behind amplifiers and wiring shit. Every square inch of my studio is close-miked, and also with cameras.

"So when my buddies come over, the hard drives are burning. We play some fun stuff, we have a great time, and then when they leave, I cut it all up. It's the music with the movie - Final Cut and Performer side-by-side, as I build these little movies and put them up on YouTube. I call this place 'The Sacred Grove.' You're watching the moment of inspiration. These players are not only playing instead of miming, they're making it up. Then I add my overdubs, I add a little guitar, write some piano stuff and make these fun little tracks. And I put them up on YouTube for all to enjoy."

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.