Simon Phillips: 10 drum albums that blew my mind

Drumming great on the recordings that shaped his sound

Intro - Protocol III

Simon Phillips has one of the most decorated CVs in music, having drummed for everyone from The Who and Judas Priest to two decades with Toto. When MusicRadar catches up with Phillips, it’s the morning before a sold-out London Jazz Festival show with Hiromi and The Trio Project.

I’m going to try to go back to when I was a kid because that’s when most of the mind blowing came from.

"The performance that night is extraordinary – three musicians at the very height of their crafts playing hugely challenging music and clearly having a blast in the process. The set includes tracks from Hiromi’s next album, Spark, due out in April. The album was recorded at Sonalyst Inc. in Connecticut.

“It’s a little uncanny because it’s an exact replica of the old Power Station in New York,” says Phillips. “Now the Power Station is where Bob Clearmountain did all those amazing 80s records, Madonna, Robert Palmer, it was the really hip studio at the time and the guy who designed it, Tony Bongiovi, was called in to design an exact replica of that studio. So when we walked in, I did a double take, ‘You’ve got to be kidding me! This is amazing!’”

The material for Spark was honed on the road. “We pulled in one new song a night and started learning, in front of an audience, how to play this ridiculous music,” says Phillips. “At times it’s very embarrassing because really the only person who knows the music is Hiromi because she wrote it and Anthony and I are still learning not only the music, but we’re still learning how to play the music. ‘How do I work this one out?’ It was really funny. But she’s always bullied us like that and I revel in it, I love it.”

The prolific Phillips recently released his latest solo outing, Protocol III, featuring his band with Andy Timmons, Steve Weingart and Ernest Tibbs. It’s the same line-up that cut 2013’s Protocol II but where much of that album was created through jamming out ideas, this time Phillips had something more orchestrated in mind.

“I now know everybody’s playing and their role in that band and also the sound of the band,” he says, “so I can take that as my template for writing the music. Protocol III is much more constructed, much more composed, but still with enough room for everybody to be themselves and to do what they do best. Protocol II was the start of the project so I wanted it to be very different to previous solo albums where I was fairly autocratic and I had everything planned, I’d made demos of everything. It was totally the reverse, it was ‘Okay, here’s a bunch of things, I like some, I don’t like others, let’s see what happens.’ That established the identity of the band and now I have that to write for so it was really fun.”

To pick out the albums that blew his mind, Phillips is digging deep into his formative years. “I’m going to try to go back to when I was a kid,” he says, “because that’s when most of the mind blowing came from.”

1. Buddy Rich, Mercy Mercy (1968)

“That was the first Buddy Rich album I owned and I absolutely loved it.

"I used to play along with it, I learned that thing from back to front, top to bottom and I used to even try to set my kit so it looked exactly the same as the picture, although I don’t think there is a picture on that album cover but there is a picture on Big Swing Face, which was the next record I got.

"I held the photo up that’s on the back of the album and looked at the drum kit, adjusted the tom-tom a little, looked at it again, and that’s before I played along with the album.

"I tried to tune the drums so they sounded like they did on the record, which was impossible, but I got close. I would say either of those albums, but Mercy Mercy was the first one that I got.”

2. The Chicago Transit Authority, The Chicago Transit Authority (1969)

“That was my first real rock ’n’ roll band that I fell in love with and also my first rock ‘n’ roll guitar hero, Terry Kath, more than Hendrix.

"It was the brass section that drew me into the band because I spent my life with a brass section up until that point, I only understood music with brass basically, all the big band music my mum played, my dad’s music and I just loved it, Stan Kenton, Don Ellis, Count Basie, I just loved the sound of a big band basically.

"Chicago Transit Authority, I love Danny Seraphine’s drumming, so creative within a rock context. Of course in those days most rock drummers were really jazz drummers because that’s what they started out playing, they just morphed into being rock drummers that we know like Ian Paice, John Bonham, they all started off playing Dixieland.”

3. Don Ellis, Don Ellis At Fillmore (1970)

“With Ralph Humphrey [on drums]. I was a huge fan, and still am, of Don Ellis. He died way too young. When I’m in the States, I feel most universities and music colleges have a wonderful arsenal of Buddy Rich arrangements, Stan Kenton arrangements, Woody Herman arrangements, but very few have any of the Don Ellis arrangements.

"Now they’re pretty tricky but I just feel that the music educational system in the States should be honouring Don Ellis a lot more. All his writings are stored at UCLA and I’ve been in contact with his son because I wanted to do a couple of arrangements at the last PAS [Percussive Arts Society] show that I did a few years ago.

"He very kindly allowed me to get copies of these and I sent them to the big band which was actually the DC Army Blues Band, great big band. We got two of these arrangements out and they loved playing them, they just said, ‘Wow this is tough, but it’s great.’ So I always push Don Ellis, a huge inspiration for me, I learned how to play in odd meters and I learned a lot of my music from him.”

4. Quincy Jones, Smackwater Jack (1971)

“I used to play along to all of Quincy’s albums, Walking In Space, Smackwater Jack, Gula Matari. The drummer was Grady Tate.

"I loved his playing, loved his sound, his straight-ahead, his swing, quarter notes on the ride cymbal, boy I tried to emulate his sound and his playing as much as I could.

"I used to practice for hours. Jones did a cover of Marvin Gaye, What’s Going On, a beautiful cover with Freddie Hubbard playing trumpet, Hubert Laws playing flute, Toots Thielesmans playing harmonica, Harry Lookovsky playing an amazing violin solo which was transcribed from Toots Thielesmans’ guitar solo, a really cool arrangement.

"He did the theme from Ironside, that’s where Jeremy Richardson plays a beautiful soprano sax solo. I love that record, I still play it now.”

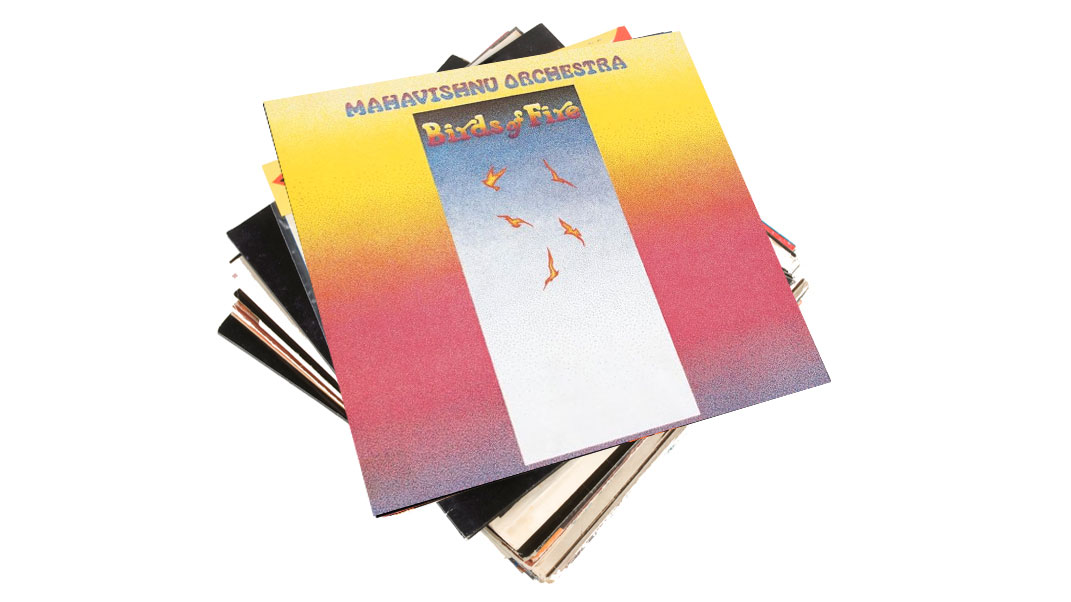

5. Mahavishnu Orchestra, Birds Of Fire (1973)

“Billy Cobham became my all-time idol around that time. That was it for me. This is the way into the rock ‘n’ roll fusion, changed the sound of my drums, changed my drumming, that’s what did it.

"My main inspiration for the double bass drums was first of all Louie Bellson, secondly looking at all these wonderful drum catalogues going, ‘What is it like to play two bass drums?’ And the main guy who is responsible, and he might be very surprised about this, was Tommy Aldridge in Black Oak Arksanas.

"I saw them on an Old Grey Whistle Test and the way Tommy was playing double bass drums, I said, ‘That’s how they’re supposed to be played!’ Twin 26” bass drums and I’d never heard anybody play with such accuracy before.

"That’s how I’d always imagined two bass drums should be played. It was after that that I heard Billy and went okay, that’s it, done deal. I must buy a second bass drum!”

6. Return To Forever, No Mystery (1975)

“Lenny White. First of all, let’s go back a little bit, his straight-ahead playing when he was playing with Freddie Hubbard, he has a very distinctive touch and even to this day when we hang out and I see him play, his touch on that ride cymbal is just so special.

"He has a very light touch and he gets a beautiful sound out of his drums. He moved over to San Francisco for a bit, he was hanging out and playing with [David] Garibaldi and all those bands that Tower Of Power came up with, so he got into that super funk displaced beat shit.

“He really brings that out in his playing and brought that into Return To Forever and I think that helped define his fusion playing, his more rock ‘n’ roll playing. That’s how I perceive it anyway, he might totally disagree! He does bring a real nice super funk vibe to his playing and I love it.”

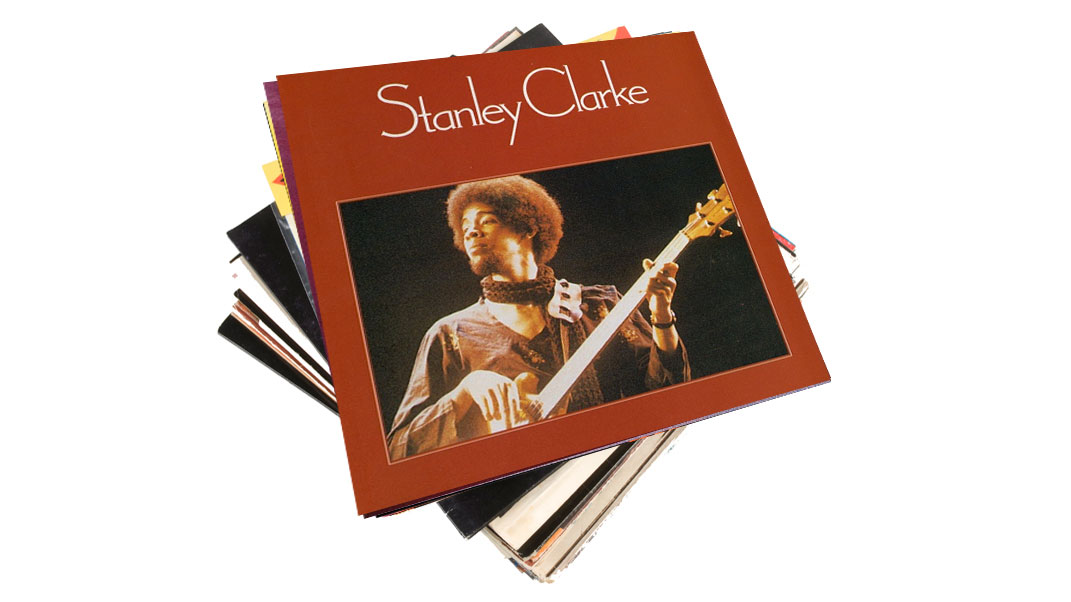

7. Stanley Clarke, Stanley Clarke (1974)

“With Tony Williams on the drums. That’s what really first turned me on to Tony’s playing and his sound.

"From that moment of listening to Stanley’s record I was really drawn to his playing and I don’t want this to come out the wrong way, but I recognised a couple of things that I was into playing that I heard in his playing.

"I had to start collecting all the records I could with him playing on. This was such a compositional drummer and to this day if I need inspiration as a soloist, I’ll go and listen to some Tony Williams because he just breaks it down. He wasn’t the fastest drummer, he didn’t have raging technique, not like Billy [Cobham], not like Dennis Chambers, but he had something that was just so musical.

"When he plays a single stroke roll, it’s got a vibe and he could create that out of one drum. You knew it was Tony. His touch was just gorgeous, so melodic, I always say Tony could play a whole note.

"Now as we know that’s an impossibility on a drum kit, but the way I perceive him, he could do that, he could play tied notes just like a tenor player.”

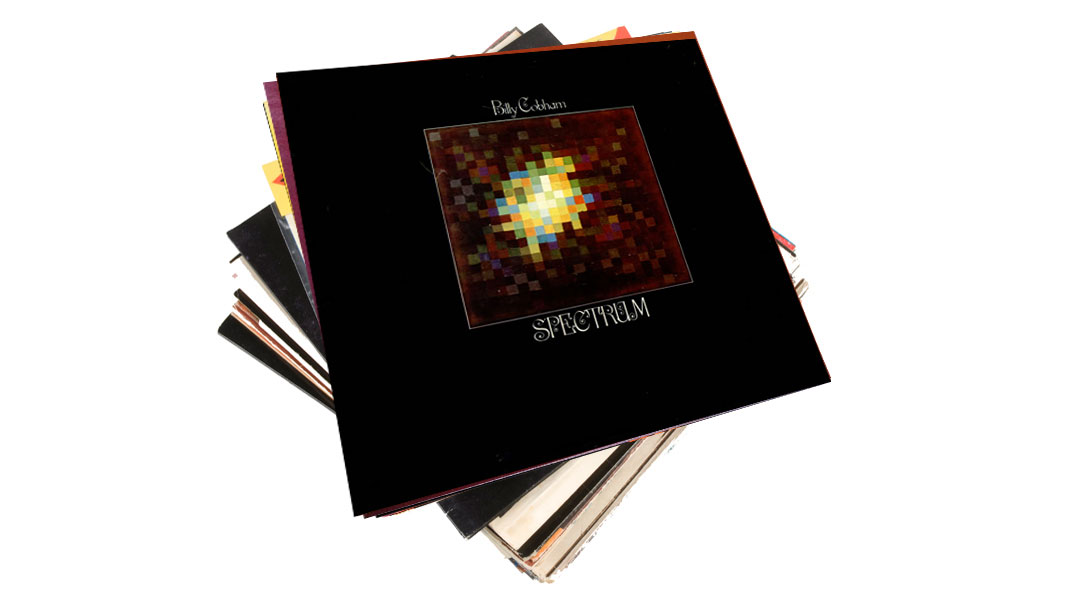

8. Billy Cobham, Spectrum (1973)

“Obviously the sound of the record is beautiful, Jan Hammer, Tommy Bolin and of course Lee Sklar.

"The great thing is I got to play with three people on that record, Lee, Jan and Billy, we’ve done double drum stuff together. I love that record.

"A few of those compositions are standards now, that’s the amazing thing. Every jazz bar band in the world plays Stratus. That’s so cool.

"He’s also been sampled many, many times, it’s fantastic. I think that’s a major record.”

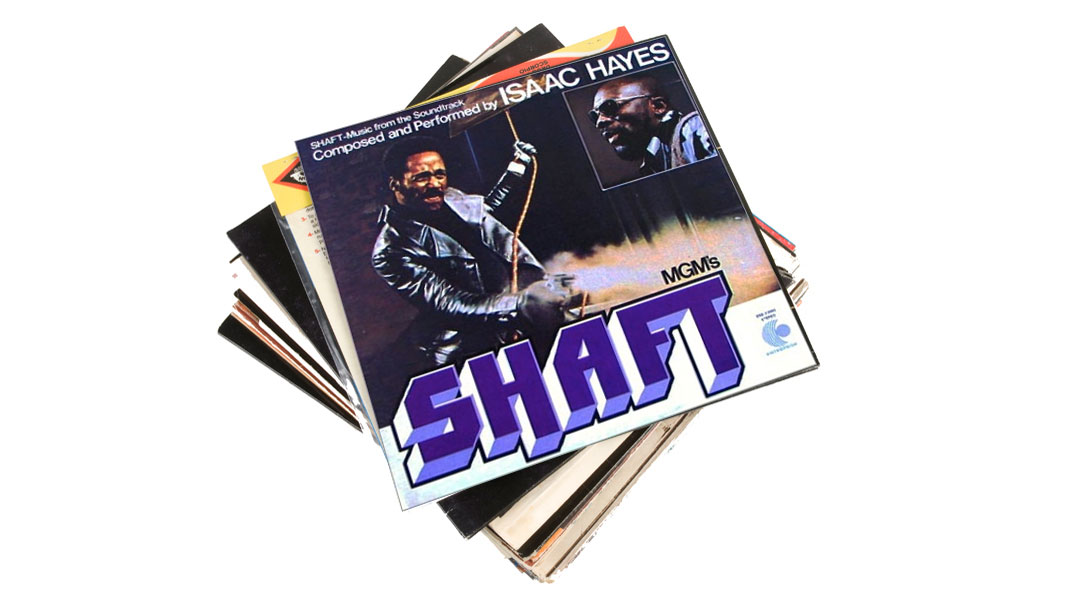

9. Isaac Hayes, Shaft (1971)

“I had that on serious rotation. I don’t even know who the drummer was, I tried to find out ever since but the grooves, the music – fantastic!

"That’s where I learnt to play that style, how to play R&B, how to play a blues. I loved it so much. I wasn’t just into listening to fusion and jazz, I was really into that music too. I grew up in the era where a lot of my friends were listening to soul.

"That was their main music, it wasn’t British pop. These were the friends I went to school with. I’ve got to put Isaac Hayes in because I think he broke a lot of barriers down especially at that time writing for film, being a black writer in the film scene, the same with Quincy Jones, he had to break into that scene.

"It was very difficult. That was a very white majority profession at that stage. I still play that record.”

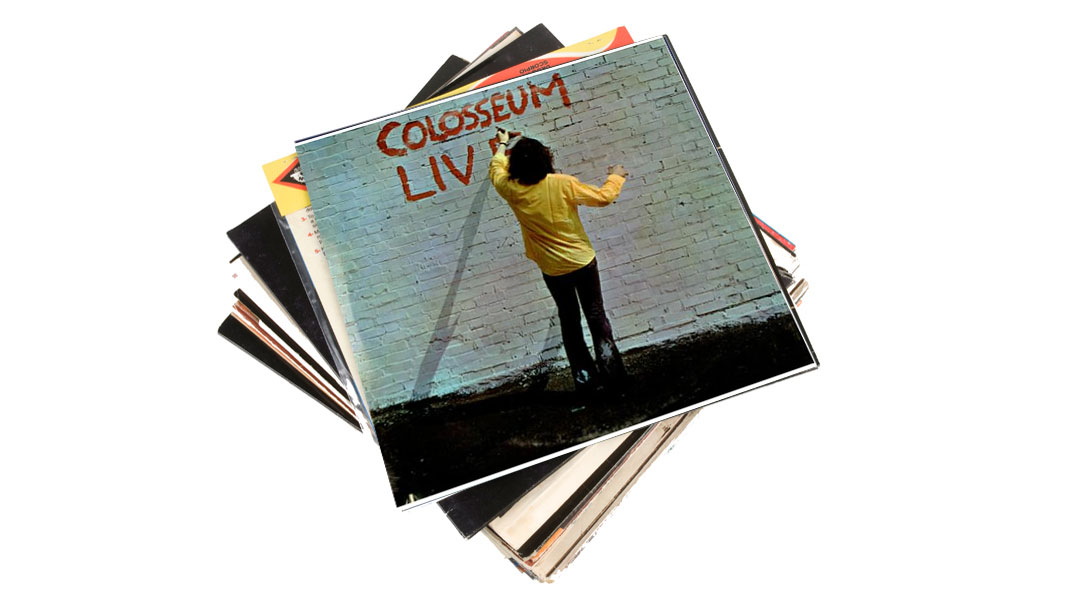

10. Colosseum, Live (1971)

“That Colosseum album with Dick Heckstall-Smith, Chris Farlowe, it’s a double album. I remember two records, there was one before Chris Farlowe joined and then there was the live one.

"It was recorded at a university somewhere. Dave Greenslade [keys player], I ended up doing his solo record not long after that, just a few years actually. The guitarist was Clem Clemson.

"I’ve got to say that was big influence too, the way Jon played, beautiful really. It was old school but he got a great sound and at that time was one of Britain’s leading drummers. Fantastic, really. Obviously a big influence.”