Ged Lynch talks Black Grape, Peter Gabriel and battling Vinnie

Drum hero looks back on Britpop infamy

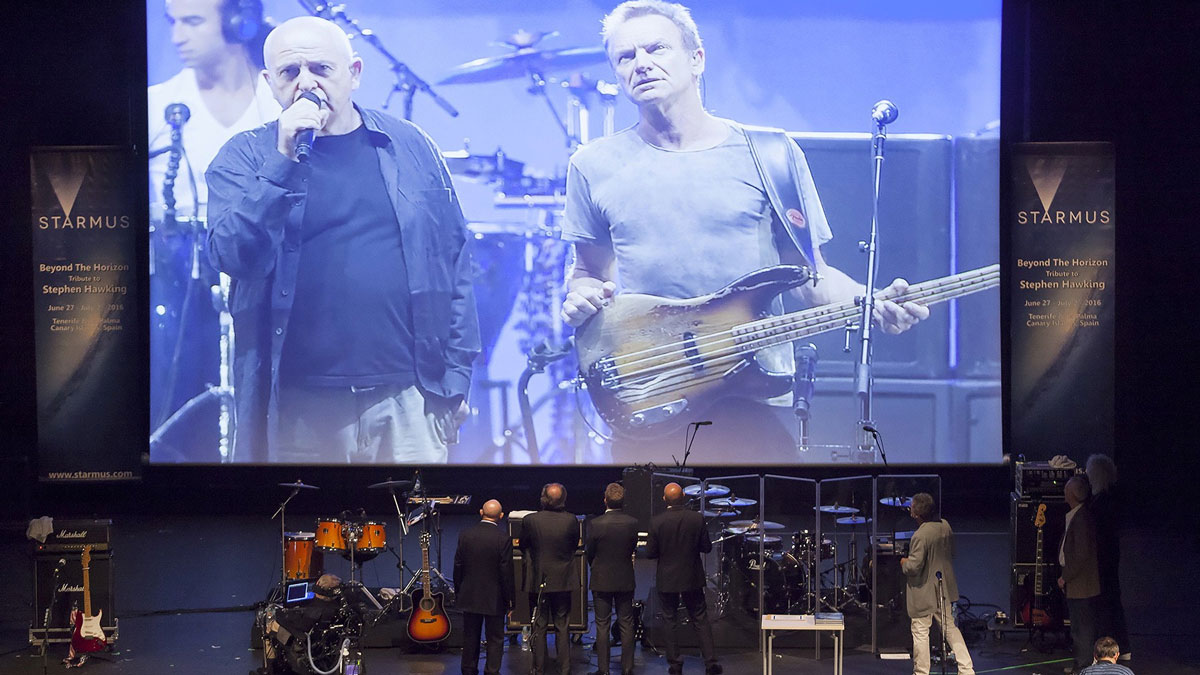

"Working with Sting is going to be... silly!"

I’m a real pop monster,” explains British drummer Ged Lynch, for a while now Peter Gabriel’s go-to sticksman and percussionist.

“The thing that gets me excited has always been singers, I’m more likely to be into a singer than I am to be into a drummer. The song and the singer are the reasons I play

music.

“Drums are great, don’t get me wrong, but the priority is what Peter’s doing. ’Cos I’ve seen him slay people at 100 yards with a song. When I was a kid I was into the Police, so working with Sting is going to be... silly! Just silly!”

When we meet Ged at Real World Studios near Bath, he is just about to embark on a huge North American tour with not only the So and Genesis star, but also Sting, with the British music megastars trading songs in megabowls from Montreal to Milwaukee. For Ged, this also means sharing a stage with Sting’s drummer of choice... who only happens to be Vinnie Colaiuta.

Ged explains: “We’re going to mix the bands, and two drummers is a tricky thing. So I think there’s a

plan to do some pieces where we orchestrate drum parts and then other tunes where I’ll be playing perc – because it’s just going to work musically, it’s going to give us a broader choice.

I’ve never met Vinnie but I’ve heard really lovely things. It’s just going to be amazing to play with players like that, it’s going to be an education!

“I was worried having two drummers with a four-piece band was just going to sound like Gary Glitter back in the ’70s! I’ve never met Vinnie but I’ve heard really lovely things, I was talking to Andy Gangadeen and he said he was a darling of a man. It’s just going to be amazing to play with players like that, it’s going to be an education!”

Blackburn-born Ged got his first break playing percussion with Manchester rap artists The Ruthless Rap Assassins in the early ’90s. Rapper Kermit from the band went on to form Black Grape with the Happy Mondays’ Shaun Ryder and Bez, and dragged Ged along for the ride as the band’s drummer and percussionist.

Black Grape had two hit albums, 1995’s It’s Great When You’re Straight... Yeah! and its 1997 follow-up Stupid, Stupid, Stupid. The band’s mix of post-baggy party music, funk, indie rock and electronic sounds caught the lad-culture zeitgeist and Ged and the boys were on TFI Friday almost every week.

Behind the apparent madness and mayhem that has always accompanied Messrs Ryder and Berry was a supremely tight band, Ged in particular keeping things locked down while the party sometimes seemed out of control around him.

After Black Grape, connections made with the hit albums’ producers kept Ged busy throughout the ’90s, before he became a fixture at Peter Gabriel’s Real World Studios, and through his skills as a percussionist came to work more and more with the artist.

Top of the pops

Ged caught the bug, like many British musicians of his and previous generations, from watching pop bands on the telly.

“It was Top of the Pops,” he recalls of his introduction to drums. “I just sat there going, ‘That looks like the most fun it’s possible to have, so I’ll do that!’ Things were much simpler then. You joined a band and you did covers and you learnt how to play drums, and then you decided you needed to be an originals band because it wasn’t cool to do covers. And that was the journey, from watching the telly.”

Alongside his development as a drummer, Ged learned to play percussion, which both expanded his rhythmic voices and also got him work.

“I was doing some gigs in Manchester and there was a percussionist called John Slater playing congas properly,” says Ged. “I’d seen the Mickey Finn type thing, but he was actually doing stuff that you were kind of like, how are you doing that? We became friends and I started copying his stuff, and then you realise you’ve got all these different voices – it wasn’t just kick, snare, hat, tom. it was nice to think, there’s more here. It was a musical thing really, I was just attracted to the different palettes.”

Ged began working with DJ/producer Greg Wilson, one of whose in-house productions was Manchester rappers ruthless rap assassins, and one thing led to another.

Kermit rang and said, ‘Hey we’re doing this thing with Shaun from the Happy Mondays.’

“They were going out live, they already had a drummer, but they decided that colour and movement would be good so I started doing live shows with them. And it was great, I think it was the first time I’d done purely percussion with a drummer and beats and DJ, it was interesting.

“That’s how I met Kermit, which is the Black Grape hook-up. Kermit rang and said, ‘Hey we’re doing this thing with Shaun from the Happy Mondays.’ Kermit had brought me in and I ended up finding the band, except [guitarist] Wags, Wags was already there. But I brought in the bass player and the keyboard player, so we were the core thing.”

Keeping Bez in check

Ged began a chaotic but fruitful couple of years with the frontman-heavy party band, which Ged describes as “absolutely off the cliff”. But, no matter what was going on onstage with Kermit, Shaun and Bez, the band always seemed really tight live.

“It was interesting, just keeping the wheels on,” he muses. “The guy that everyone wanted to see was Bez, we’d be playing, roaring away, Kermit would be doing something, Shaun would be doing his thing, but Bez, because he used to just patrol the frontline of the stage and people were just... it was Bez! And it worked. Sometimes it didn’t, sometimes the wheels came off, but broadly speaking it just worked because people didn’t really see the technical side of things, it looked like chaos. It was a party on stage! But it was all to click!”

Playing to click was something Ged nailed very early on, and it’s helped him get the call-backs since. “I was lucky,” he says. “I think I was that generation of drummers that was told specifically there was no point playing drums, we’ve got a machine now, so you learned quickly.

I was that generation of drummers that was told specifically there was no point playing drums, we’ve got a machine now, so you learned quickly.

“And also it’s not that it was some great chore, it was great fun playing with drum machines, it became part of your thing. You became attuned to such good time very, very quickly, so click has always been there. And in relation to this gig [with Peter Gabriel and Sting], some things have to be monstrously on it.”

Ged was Black Grape’s percussionist also, but – at least in terms of maracas – the band had another perc player in Bez. Did he work with Bez to complement what the other was playing?

“No, there were conversations but I think Bez had bigger fish to fry in regard to live performance, he wasn’t focussed on accuracy or the kind of things that a musician, or a dweeby percussionist, was going to be obsessed with. That wasn’t Bez’s thing!”

A broader palette

For It’s Great When You’re Straight... Yeah!, the band had drafted in two talented producers, Danny Saber and Steve Lironi, who helped steer the album into chart-smashing territory. Striking up a productive relationship with them would bear further fruit for Ged’s post-Grape career.

“That was the real bonus for me,” confirms Ged. “They did that record and it went to Number One, but I was friends with both of them and they didn’t carry on doing production together, they went and had two separate careers and suddenly I was their guy, so for the ’90s I was really lucky.

“Because you know, it’s like once there’s a Number One album and the producer says, ‘I want Ged,’ they’re like, ‘Ged who?’, ‘Black Grape Ged,’ ‘Oh yeah, that’s a good idea. We should do that.’ It wasn’t as if my playing became extraordinary in that period but the minute you had a Number One album that seemed to be an excuse for every record company to say yes.”

It’s like once there’s a Number One album and the producer says, ‘I want Ged,’ they’re like, ‘Ged who?’, ‘Black Grape Ged,’ ‘Oh yeah, that’s a good idea.'

Black Grape’s mix of funky grooves, percussion and electronics also helped Ged to think more broadly in terms of his musicality, which, he recognises, made his skills more marketable.

“I think I got my head around not seeing drumming as the drumset,” he says, “and still to this day I don’t see myself as just a drummer. That sounds like being just a drummer is a bad thing, it’s not, but the idea that there’s this palette... if I’m working for a producer I won’t turn up with just a drum kit, even if it’s a drum section, I’ll bring everything because I don’t see it as that – it might just be, give me two tracks’ triangle, one tambourine track and some brushes over the top, and that’s how I hear it.

“The producers I’ve worked with, they’ve gone, ‘Great, yeah,’ and, ‘that’s a keeper.’ Rather than just turn up and play drums. But I suppose it’s like being given confidence, isn’t it, if a producer lets you do something? And then it becomes a marketable thing.”

What the gig calls for

Little by little Ged became a fixture in Gabriel’s musical camp, though he never felt he would get a crack at the big live dates because, after all, peter’s go-to drummer has for years been the mighty Manu Katché.

“I’m just one of [Gabriel’s] guys,” says Ged modestly, “he chooses from a chocolate box of guys. But I was really lucky, Peter had a one-off show in Seattle, Womad, and Manu couldn’t do it. Spin on a couple of years and I did some more recording and then there was a point where I knew my name was in the hat, but with Manu, and all these guys he’s got, I was like, ‘I’m the studio kid, I’m not gonna get a bite of that.’

I think all you can really try and do is to help. Is what you’re playing helping? Is it supporting the song? Is it bringing energy to the song?

“And then one day I came home and the answering machine was flashing and it was Peter: ‘We’d like you to come with us.’” Ged grins, “’Cos it’s [bassist] Tony Levin, it’s [guitarist] David Rhodes, it’s Peter – it’s the gig from heaven, it really is, it’s a lovely thing. I’m so lucky.”

Ged’s broad range of work across many different genres means he must have to change gears pretty regularly... one minute he’s doing the big gigs like Sting and Gabriel, the next working with folk artists like the Carthys.

“You have to put on different hats. That’s why I’m in here [preparing for the tour at Real World], we’ve not run at full Madison-Square-Garden for two years and so it’s like I’ll need to run the engine up into fifth gear now, ’cos I’ve been playing quite gentle stuff...”

Playing beats made famous by such skilled players as Manu, Vinnie and more must call for some pretty good chops on Ged’s part. But Ged is modest about that side to his playing.

“I know what you mean by that, this is a very interesting area. I try to not... how to talk about this without upsetting loads and loads of people? I’m really only concerned with the song that I’m playing, I try to be concerned with what it’s all about, why rather than how.”

Speaking of Vinnie, it’s time for us to address the – let’s be honest – awesome fact that Ged is going to be sharing the stage and even trading licks with one of the drumming world’s most revered players. Is a drum battle on the cards?

“I’ve got to say I don’t even know what that means!” says Ged. “The idea of that is... I’ll just start laughing. Someone would have to explain to me what that means. Because that’s a bloodsport! And that’s not really how I see music.

“I know there’s a whole industry of that, but I’ve got to be honest, that’s got nothing to do with me. I’d start laughing. Because, what are we doing there then? Everybody knows that Vinnie is god in that sense!”

So, does Ged have any advice for supporting the song?

“I think all you can really try and do is to help. Is what you’re playing helping? Is it supporting the song? Is it bringing energy to the song? Whatever you can do with the drum kit is to help and be aware of what you’re playing"

Has he ever got it wrong though, have an artist turn round and go, ‘what are you doing?’

“No, I don’t think so...” he says, carefully. “You mean like, what are you doing, you ruined my song!? I don’t think I’ve ever ruined anyone’s song! That might be a nice epitaph...”