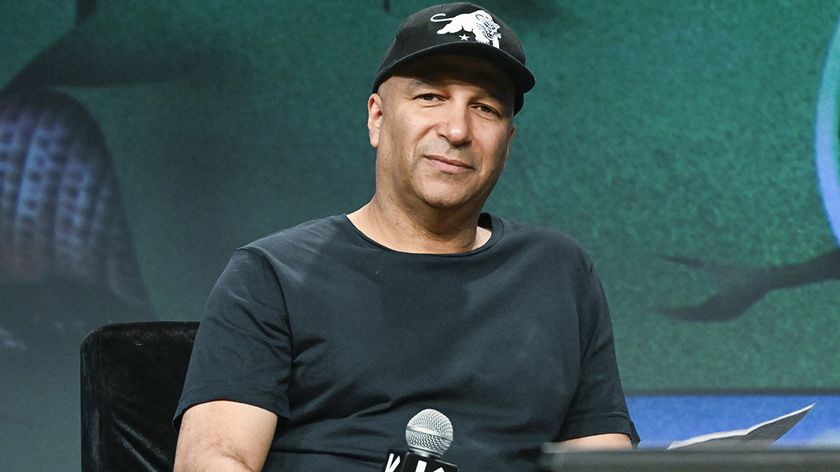

Gavin Harrison's top 5 tips for drummers

On his upcoming solo album Cheating The Polygraph, Porcupine Tree drummer Gavin Harrison reworks, rearranges and, in many ways, re-imagines eight of the band's songs in a big band fashion. It's a fresh and daring concept that started to evolve in 2009, after he was asked by Buddy Rich's daughter, Cathy, to perform at a memorial concert for her late father.

"Cathy said to me, ‘You’re welcome to play any of Buddy’s tunes, of course, but what would be really fun is if you did a song from your band,'" Harrison explains. "My band's music isn’t anything like Buddy's, obviously, so I thought about it, and then I got together with Laurence Cottle, a big band arranger, to see what might work."

Harrison had firm ideas for the sound he was looking for: "I told Laurence, ‘I don’t want this to be funny," Harrison says. "It couldn’t be comedy, cheesy, ‘rock does swing’ or anything like that. I thought it should be serious music. We went with that approach, and it came out great."

The 2009 memorial concert didn't pan out (although Harrison did participate in a 25th Anniversary Buddy Rich tribute show in 2012), but once Harrison and Cottle had worked up the first tune, they decided to try another. "I asked Laurence to write an arrangement of Cheating The Polygraph. Once we did that second piece, I said, ‘What about a whole album?’"

Over a five-year period, Harrison and Cottle worked on a selection of Porcupine Tree songs, reworking arrangements and cutting them apart, recording brass with demo drums and then recording keeper drum tracks after the new arrangements were complete. “It was a fascinating process," Harrison notes. "There were actually 10 songs that just wouldn’t work. We started them, wrote an intro or a verse, a middle-eight, but we ultimately decided there wasn’t enough material in certain songs to work with. They were more about atmosphere, sound and vibe than strictly chords and melody. So I gave up on those pieces and concentrated on the ones that gave me enough to rearrange.”

Of the finished album, Harrison stresses that listeners unfamiliar with Porcupine Tree's catalog won't have a hard time appreciating the music. "They're enjoyable pieces, and they sound nothing like the originals," he says. And despite the big band milieu, the drummer emphasizes that his agenda was decidedly anti-retro: “We’re not trying to do Glenn Miller. This is much more Frank Zappa, Don Ellis, Lalo Schifrin, Patrick Williams – some of the more modern big band thinkers. I’ve always been fascinated by modernism in art, so this album follows through on that futuristic-thinking concept."

Gavin Harrison's Cheating The Polygraph will be released April 13 in the UK, April 14 in North America, April 17 in Germany and April 22 in Japan. Physical pre-orders are available at the Kscope webstore. It is also available as a vinyl pre-order, as a CD/vinyl bundle pre-order and via iTunes.

On the following pages, Harrison runs down his top five tips for drummers.

Work on your timing

“Without a doubt, this is the most crucial tip. It’s the one thing that’s going to get you employed. If you think your timing is already great, maybe you’re just not listening hard enough.

“You need to get good at listening for the details. Because you'll be learning by yourself most of the time and your teacher won't be standing over you 24/7, your ears will be your teachers and your benchmark. So you might say, ‘How good should my time be?’ And I’d say, ‘As good as your ears detect you to be.’ So as your ears get better, you’ll start to notice when your timing isn’t right.

“It all comes to working on your listening. I’ll go on YouTube and look at drummers, and sometimes I can immediately hear when they’re going wrong. If I put on a tape of me practicing the drums from 25 years ago, now I can tell you exactly where I’m off. Twenty-five years ago, my ears weren’t good enough to easily pick up on where I was going wrong.

“You need to be in sync with yourself. If it’s hi-hat, snare and bass drum, you need to be like three drummers playing together. If one or two of them aren’t in sync with the best one – let’s say the right hand on the hi-hat – then everything else will be off. Even tiny little errors will make the whole of what you’re doing sound wrong. You’re going to speed up or slow down depending on what the problem is. It’s not that you’re not trying; it’s because you’re not listening.

“It’s hard to think of this stuff while you’re playing. It’s easier and much better to record and listen, record and listen. It’s only when you take the time and learn to hear what's really going on with your playing that you’ll be able to isolate what’s wrong and work on improving the problem.”

Buy a bass guitar

“Buy or borrow a cheap bass guitar and learn to play a few easy lines. Try playing a groove, even if it’s just one or two notes, or even better, play with a drummer friend. You’ll quickly learn to hear what bass players want from drummers. And all they want is really good time.

“I’ve done this. I’ve had professional drummers come by and I’ll notice, ‘Wow, this really feels different from what I was playing last week, because this guy puts the beat in a slightly different place. He’s not speeding up and he’s not slowing down; he’s just putting the beat somewhere different, and I’ve got to adjust to get with this guy.’

“You learn a lot when you move away from your own instrument. It’s like the way you only understand your country when you go abroad and you look back at it. You really understand what it’s like to be English when you go to France or Spain or the United States and Canada. You look back and think, ‘God, if I never left that country, I’d be locked in that little mentality.’ The same is true for playing music.

“You don’t have to be a great bass player to get something out of this. Just pick one or two notes. Try playing it with a click, try playing it with a drum machine, and try playing it with a drummer. You’ll really learn a lot about timing, placement, and most importantly, you’ll discover what a bass player wants from a drummer.”

Film yourself drumming

“Look at your movements by filming yourself. This is the step up from recording yourself. Back in the day, we recorded ourselves on cassette – that was the only technology we had – but you can learn a lot more about what you need to correct about your playing when you can actually see it. And it's easily done nowadays, so there's no reason not to do it.

“Things should look relaxed and easy, fluid, feline. You can watch Omar Hakim or Manu Katche with the sound off and you’ll still think, ‘Yeah, those guys can play.’ You can just tell they’ve got rhythm coming out of their pores – and it’s all in the way they look. And likewise, you can turn on the TV with the sound off, and you'll see some other guy playing and think, ‘God, he looks really stiff.’ Then you turn the sound on and you go, ‘Yep. He sounds stiff. I knew it.’

“You’ve got to see if you’re tense or if you’re putting your body into uncomfortable positions. Are you holding your breath when you play a fill? Are your drums set up in the easiest ways to reach each piece? I see people set up their drums in such weird, difficult-to-play ways - it boggles the mind. When Porcupine Tree do festivals, I’ll walk around backstage and see something like six drum kits set up on a riser, and I’ll look at them and think, ‘Man, these things are gonna be so hard to play.’ The angles, the heights of things – everything’s where you can’t get to it.

“Think about where you place your drums and cymbals, how high or low you sit at the kit, and how comfortable you look. Are you relaxed? Are your shoulders up? Are you slouched over? Are you pulling faces and biting your tongue and doing weird things? All of that is tension, and tension is not conducive to playing good music with feeling. So try filming yourself when you play, and take a good look at what you’re doing.”

Learn to read notation

“It may not be at the top of your priority list, and you might be in a lot of situations where no one’s ever asked you to read, but knowing how to read notation will greatly expand your drumming in many ways.

“You’ll be able to access lots of great books, and you’ll be able to understand more complex rhythms. I could never have worked out so many passages of music if I didn’t know how to read. King Crimson is a great example – if I couldn’t read, my ability to grasp the music efficiently and effectively would have been greatly diminished.

“Many times in my career, someone has said, ‘Can you come and do this gig? There’s no rehearsal, there’s 20 songs, and it’s in two days time.’ Now, if you’ve worked out how to read and write charts, you can do the whole concert without any rehearsal and without making any mistakes. If you can just get your reading chops up to the point where you can notate anything that you can hear, and you can make bar charts of any song, you’ll be able to whip out your folder, go on stage and play without any worries.

“In rehearsals and sessions, you’ll save so much time if you can write charts. The producer or artist will say things like, ‘In the second chorus, can you push the last eighth note of the third bar, and can you make an accent on the second sixteenth of the sixth bar?’ – things like that. They’ll throw all of this stuff at you, all of these requests, and you can just drop it into your chart and know what it’ll sound like, because you can see it.

“Drummers have to be the solid rock of the music. Think of yourself as the air traffic controller for the band. That’s the way the other musicians have to view you – you’ve got the responsibility and reliability of the person guiding in the planes. They need to have that trust in you to think nothing is going to go wrong with you sitting behind them. That’s the attitude I try to play at. I’m the drummer, but I’m also the air traffic controller. I’m not going to let any disasters happen. I know what I’m doing, I’ve got my charts, or I’ve rehearsed the song so many times with the charts, so I know what’s coming next.”

Challenge yourself with a short list of questions

“When I’m working on a song, whether it by myself or with a band, I ask myself, 'How can I make this piece of music feel better? Maybe if I simplify my pattern, I could play it easier.' The most important thing is that it feels good.

“So I’ll ask myself, ‘How can I make this rhythm more interesting?’ Not more complicated, but not the most obvious thing I could play. Is this the most musical part I could play? Bearing in mind that playing nothing is also a good musical decision. Sometimes you’ll say, ‘I’m not gonna play the first verse. I think it sounds much better to come in on the chorus. It’ll sound more powerful.’

“Are the fills helping? Do they make the song go places? Are they developing the arrangement and the shape of the song in a musical way, or am I just trying to impress young drummers and score points by playing flash fills? You have to give up your ego and say, ‘A simple fill here is going to help the song.’ It could be an interesting simple fill – it doesn’t have to be boring – but there’s no need to play around the whole kit and hit every cymbal.

“How can I improve my sound for a particular song? Should I hit the snare drum harder? Should I change the ride cymbal? Maybe the ride cymbal is the wrong one for this song. Maybe the tuning of the toms isn’t right for this song.

“A producer will ask himself these sorts of questions, and so should you. You should ask yourself, ‘What does this song need?’ More and more, I’m doing sessions remotely, in my home studio. People are sending me files, and they’re trusting that I’m going to make those producer decisions. I’m not going to turn it into a drum solo; I’m going to play in a way to make the song sound best.

“In a roundabout way, that’s also making me sound best. The way to show off is to simply not show off. When you make the song sound great, people will notice.”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

"They said, ‘Thank you, but no thank you - it’s not a Monkees song.’ He said, ‘Wait a minute, I am one of the Monkees! What are you talking about?’": Micky Dolenz explains Mike Nesmith's "frustration" at being in The Monkees

“There’s nights where I think, ‘If we don’t get to Paradise City soon I’m going to pass out!’”: How drummer Frank Ferrer powered Guns N’ Roses for 19 years

"They said, ‘Thank you, but no thank you - it’s not a Monkees song.’ He said, ‘Wait a minute, I am one of the Monkees! What are you talking about?’": Micky Dolenz explains Mike Nesmith's "frustration" at being in The Monkees

“There’s nights where I think, ‘If we don’t get to Paradise City soon I’m going to pass out!’”: How drummer Frank Ferrer powered Guns N’ Roses for 19 years