Nigel Olsson, with trademark gloves and headphones, behind his DW drum kit during an Elton John concert in Sydney, Australia, 2008. © Bob King/Corbis

"Playing live is just as exciting today as it was 40 years ago," Elton John drummer Nigel Olsson told MusicRadar. "I know Elton feels the same way, especially when we play Madison Square Garden. The Garden is always like one big party."

Of the crowds that packed the iconic New York venue for two recent sold-out shows, Olsson said, "Obviously, the audiences are different now than when we started out. We've got everybody from kids to their grandparents." Chuckling, he added: "And there's granddad on drums!"

As his longtime bandmate, guitarist Davey Johnstone, also pointed out, the Garden holds a special place in the hearts of certain members of the Elton John camp for another reason: "It's where John Lennon played his last live show, in 1974, during one of our concerts," Olsson said. "What a night. Electricity was in the air. Every time I walk out on that Garden stage, I think back to that show."

MusicRadar sat down with Olsson at Manhattan's London Hotel on the same day that we spoke with Johnstone (the two were in town, along with Elton and the rest of the band, for a Saturday Night Live appearance). The drummer and guitarist go way back, comprising half of the famed, original Elton John four-piece (which also included the late bassist Dee Murray). Olsson admitted to a fair amount of amazement that he's played with Sir Elton for over 40 years.

Not that there haven't been bumps in the road: in 1975, John let Olsson and Murray go, only to bring Olsson back in 1980 (Murray returned two years later); and then, in 1985, the mercurial superstar jettisoned his rhythm section once again - it would take 15 years, and several fits and starts, for Olsson to take his rightful place on the drummer's throne for good. (Sadly, Murray died in 1992 of a stroke, following a lengthy battle with skin cancer.)

"All in all, it's been an incredible journey playing with Elton," Olsson said. "You start out with somebody and you hope it'll last a year. Forty years and more, you never consider that."

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Many drummers have talent, but it takes a certain kind of talent to propel a drummer to the level of artist. Throughout his career with John, on landmark albums such as 11-17-70, Honky Chateau, Don't Shoot Me, I'm Only The Piano Player and Goodbye Yellow Brick Road, Olsson, an individualist with a quirky, dramatic sense of timing, has informed John's smash hits with a freshness and striking point of view.

"When people tell me that they like my style and I've influenced them, it's most flattering," Olsson said. "But really, I just tried to play what the songs needed. That's a drummer's job, and it's a job I adore."

How did you get into Elton John's band?

"In the late '60s, I was in a band called Plastic Penny. We'd had some success with a cover of a Box Tops song called Everything I Am. It actually went to number one in England, so we had to do TV and live shows. We did a few albums and some touring, but after a while we couldn't keep it going - the interest just faded. However, we were handled by Dick James' publishing company, and as it turned out, Elton and Bernie Taupin were signed to the same organization as staff writers. A nice coincidence.

"I saw Elton and Bernie around the office a lot, and eventually they asked me to play on demos. So that's how we all became friends. We'd hang out together, and it went on from there, basically."

Did Elton tell you specifically what he liked about your playing? What made him pick you of all the other drummers he could have hired?

"He just said, 'You're perfect for the music I'm writing because you don't overdo it.' During that period, drummers were mad for showing off and playing all over the breaks. Even though I valued a good fill, I knew when to pull back and let the songs breathe.

"Also, at this point, all Elton and Bernie wanted to be were songwriters. They didn't think about going on the road and making all of these albums and playing arenas and stadiums and, you know…what's happened since. Their aspirations were quite different when I joined up with them." [laughs]

You're right handed, yet your style reminds me of Ringo Starr's - who, of course, is left handed. You both seem to lead with your left hand. And when you play fills, like Ringo, you come in a tad early.

"It's just the way I play. You're right, though, I do lead with my left. I never planned it. Probably listening to people like Ringo is how it all happened. To this day, Ringo is my biggest idol. I love him. The influenced was very natural.

"I also listened to bands like Sly & The Family Stone and Redbone. Their drummers always used to hold back a little. Buddy Miles, too, he's another one. I try to play a little bit behind - it's just how I hear things. Also, when I'm playing and listening on the headphones, I'm paying attention to the low end of the piano and the vocals. All of that contributes to my style."

Like Ringo, you value taste and economy. A song like Rocket Man, for example - some drummers would've overplayed it.

"I think that comes from the fact that, on those early records, we'd all go away somewhere - Elton, Bernie, the band, along with Gus Dudgeon, our producer. Oftentimes, we'd be in the same room with Elton while he was at the piano, writing music to Bernie's words. This gave us a chance to figure out our parts. When you hear a song being created in front of you, you focus more on what's needed. It's very immediate, what's necessary and what isn't.

"On the ballads, I always knew where to put the fills in and where to leave them out. I'd think to myself, All right, going into the chorus, I need to do something interesting, so I'll do this... You're part of the storytelling process in that way. You can't go over the top on a ballad because it doesn't sound right - to me, it doesn't.

"It's so easy to play crazy and go off. People do it all the time and think it's exciting. Keith Moon could do it, but he's an exception. He was a marvelous drummer, by the way. But knowing how to do more with less, that's what I've always found challenging. A simple, well-placed pattern stands out and announces itself. Plus, it moves the music from one section to the next in a very dramatic fashion."

Much of the material on the early records dealt with Bernie Taupin's fascination with America and the Old West. Your playing suited it so well.

"I listened to a lot of American music. For many years, all we had in England were The Beatles and The Rolling Stones. Not that there's anything bad about that, but if you wanted to hear something different…well, that's when you bought records from American bands. Although I really liked the drumming on American music, I didn't intentionally sit down and go, 'This is how I'm going to play.' I guess it got absorbed somehow."

You, Davey and Dee Murray contributed backing vocals that were crucial to Elton's songs. How did you three develop your harmonies?

"We loved doing the vocal sessions because there was always a lot of laughing going in the studio. The spirit was loose and fun. Basically, we'd be left alone. Elton would sing his vocals, and then he'd say, 'OK, you guys can get on with the backgrounds.' We'd come up with our harmonies and experiment a bit. If something didn't work, we'd try another approach till we nailed it.

"Because my vocal range was similar to Elton's in those days, I'd do some harmonies that were quite similar. Sometimes it sounded like he was doubling himself, when, in fact, it was really me. Like in Goodbye Yellow Brick Road, the [sings] 'doo-doo-doo-doo-dooo' part - I wrote that. Gus said, 'Why don't you try it?' and it worked. The magic of the music, and the fact that we were all together so much, it helped us form a very tight bond as singers as well as musicians."

Elton and the band made albums so fast in the '70s. As a drummer, was that frenetic pace exciting, or did you sometimes wish you had more time to work on arrangements?

"No, it was great. The Elton John Band sound always had energy. It sounded like a band playing a song for the first time because that's exactly what we were doing! [laughs] A song can lose its freshness if you concentrate on it too much. Daniel, Rocket Man…those were one-take tracks. Most of our stuff was done in five takes or less. Elton always liked to work fast, which was good because we were always on the go. Making records, touring, TV shows - the pace was non-stop, but it was fabulous."

You used to play a Slingerland double bass drum setup. Most people associate double bass kits with harder rock drummers.

"Yes, I supposed that's true. I began with Premier - Keith Moon put me with those guys. But I was always fascinated by Slingerland because that's what Buddy Rich played. When we first came to America, I hooked up with the people in the company in Illinois and asked them if they'd build me a custom set. I wanted oversized toms, oversized kick drums, oversized everything!" [laughs]

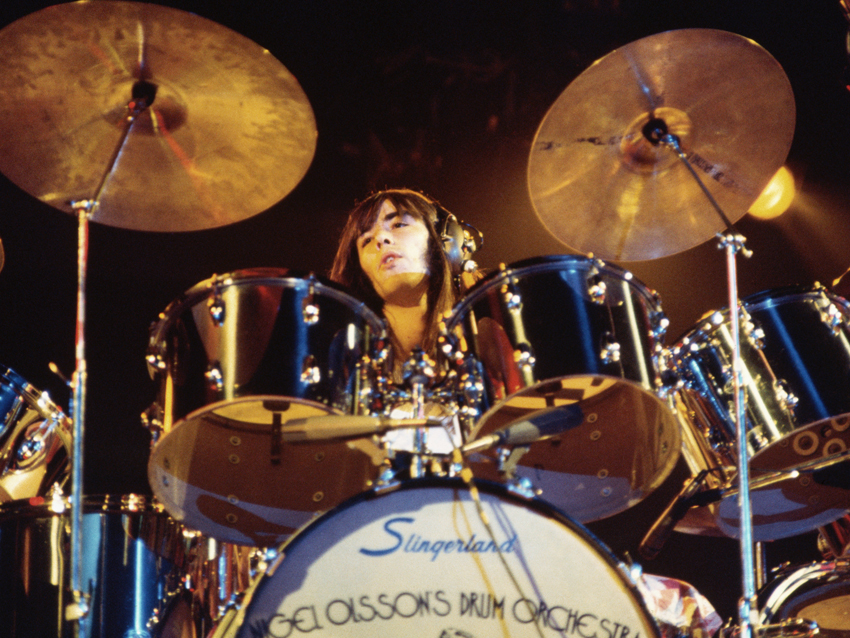

Nigel at his Slingerland "drum orchestra" kit in the '70s. © Neal Preston/CORBIS

"I had six kits made for me - one for recording, which had all wooden rims, and the others were for touring, and they had metal rims. The reason for the massive size of the drums was because I loved the low tones I could get. The deeper and bigger the drums, the richer and more powerful the sound. As for the double bass setup, it was mainly for the look, a bit of flash, you know? [laughs] One wanted to look impressive on stage, and a giant kit certainly helped. If you couldn't see me, you were certainly going to see my drums! [laughs] But the setup also helped because I liked big rack toms, which had to be mounted on their own stands."

Nowadays, you play DW Drums. What do you like about them so much?

"Their tones. [DW COO] John Good got me to the factory, and he said, 'You have got to hear these new shells.' He took one right off one of the factory benches, hit it with his fist, and it was just like… It made that sound that you want to hear. I was knocked out.

"John goes all around the world collecting different woods. Strangely enough, he found this wood at the bottom of a river in Holland, but the wood was from a tree in Ghana in West Africa. Now, I used to live in Ghana when I was a kid, so hearing this was unbelievable. I told John I had to have a kit made from that wood. We figured out the sizes, and I gave him a wild, wacky color scheme. It turned out beautifully. I use the Ghana kit in the studio and tune it very low."

During a tour, you have a few different rigs flown around the world at any given time.

"That's right. I have separate rigs that we take around with us. If we're doing a gig somewhere, another rig is being set up somewhere else. My drum tech is Chris Sobchak, and he's wonderful. He's got everything measured and put into a computer. Each setup is exactly the same. Chris can get my drums set up and tuned in under two hours. That's pretty fast."

Tell me about how you position yourself behind the drums. You don't sit very high, nor are you very low.

"No, I'm probably right in the middle. I used to sit high, but I've changed over the years. I like to sit where I can easily get a rim shot on the snare - that's kind of my signature."

During the Captain And The Kid tour, 2006. © Tim Mosenfelder/Corbis

Well, that and the gloves. How did you come to start wearing them?

"I started wearing them in 1970, probably. I saw a bass player playing with gloves - his were cut off at the fingers, of course - but still, I thought, What a great idea! You know, I was getting cuts and calluses, and instead of using bandages, which would always peel off, I decided to try gloves.

"I started out using driving gloves and then, later on, moved to golf gloves. I'm actually sponsored by Foot-Joy. Their gloves are made of very thin leather, and they allow me to feel the stick as if I'm wearing nothing at all on my hands. They do wear out: I can only do five or six shows before I need a new pair. But it's a small trade-off. And, yes, they are something of a signature, another thing I'm known for."

And the headphones. Are you listening to a click track, or do you wear the cans to protect your hearing?

"I loathe click tracks. Playing to a click takes all the heart out of the music. No, I use the headphones because I have a full 42-track mixing board, and I'm getting everything in stereo. I don't like having monitors pointed at me, blaring away. The phones gives me a great mix at a reasonable volume."

Let me ask you about one of my favorite albums, 11-17-70. Was it a nerve-wracking experience cutting that record?

"Incredibly nerve-wracking! It was just the three-piece band, Elton, Dee and myself - Davey hadn't joined yet. We went into a studio here in New York to do a live broadcast on WABC radio. There were maybe 50 people there to watch us. I remember [Billy Joel producer] Phil Ramone was the engineer. We just went for it. That red light came on, and it was like, 'OK, play!'

"A lot of people still comment on that record being one of their favorites, and I think it's because it was live, it was fresh, and it had a raw energy. It was a small band, a tight space, and we were caught up in a moment. People had heard of Elton in the States, but that really helped propel him and us as a performing act."

Hanging at the London Hotel in New York City, April 2011. © Joe Bosso

I asked Davey about this. The '70s were pretty wild times, and being in the Elton John Band allowed you access to anything and everything. Did drugs and alcohol ever become a problem?

"Well, I used to smoke marijuana and took pills sometimes. I never got into sniffing or shooting anything. And, of course, there was the groupie situation. We don't get them anymore! [laughs] Go figure. But it all did get to a point where it was slowing things down - it certainly slowed me down. I couldn't handle it, and I didn't like feeling paranoid. Eventually, I stopped all that. It's a waste of time, really. You know what's funny, though? I didn't drink back then. You know what I used to drink? Milk."

Milk? You could have been an Osmond!

[laughs] "I could have been an Osmond. It was actually in our tour rider: a gallon of milk for Nigel."

Now, that's rock 'n' roll. When Elton broke up the original band the first time, was it a huge blow, or did you see it coming?

"Oh, it was a huge blow. I didn't see it coming. At all. To this day, I don't know why he let us go. His excuse in the press was that he wanted to change the sound of the band. He tried, but I don't think he did. It was just the same songs played by different people.

"I was very bitter for a while. What was especially hard was that Elton didn't tell me - one of the lackeys from the office called and said, 'Elton isn't using you on the next record and tour. What do you think you're going to do?' I was devastated. But I pulled my boots up, made my own record and had some success with that.

"The second time I was let go, it was the same thing: someone from the office told me. After a while, though, Davey called me and asked me to sing backgrounds for the soundtrack to a Disney film Elton was doing called The Road To El Dorado. I didn't have a problem with it; I love singing backgrounds."

"They were using another drummer, a great player named Curt Bisquera. We did a promo tour for the project, but we'd slip in some hits. At one point, I think it was the song Goodbye Yellow Brick Road, Curt looked at me and said, 'This is your song to play. I can't play this.' So I played on it, it felt great, and soon after Elton said to Davey, 'I think it's time to bring Nigel back.' And I've been back ever since - very happily, too.

"The touring is very different now, and as you get older, it gets a little harder. You do a gig, and then you get on a bus for 11 hours and try to sleep, which I can never do. I get to the hotel and try to grab some sleep before the show. The concerts are always great; the traveling…not so much."

Talk to me about Dee Murray. When I spoke with Davey, he said that he thought Dee never got his due as a musician.

"Dee…[pauses] No, I don't think he did get the proper respect he deserves. I think about him every single day. Brilliant bass player. Wonderful guy. Dear, dear, dear friend. A musical genius across the board.

"Bob Birch, our current bass player, idolizes Dee. And I'll tell you, there's times when we're in the studio and we'll be recording a track, and if I close my eyes, I feel as if Dee is in the room - that's how close Bob can get to Dee's sound. But you can never replace a guy like Dee. It's impossible."

The song Funeral For A Friend/Love Lies Bleeding is such an epic, with so many moods and changes. How did you work out what to play on it?

"Again, we heard it as it was being written, and it was the magic of Elton, Bernie, the band, Gus and our engineer [David Hentschel] - we were all on the same wavelength. It just happened. It was so easy, and everything just flowed. We followed one another and knew where we had to go."

Can you point to specific songs and albums that you are particularly proud of from a drumming standpoint?

"Goodbye Yellow Brick Road, Captain Fantastic and Don't Shoot Me. Although Honky Chateau was a pretty decent album, too. I call my playing 'descriptive' on those albums. I tried to do my part in bringing the lyrics to life. You can actually do that on the drums if you allow yourself to feel the music and let your imagination take over. Of course, it helps when you're playing some pretty astounding songs!" [laughs]

Next page: Nigel Olsson's drum setups

1. The Studio Kit (nicknamed "Ghana") is DW set featuring African Ghana wood outer-ply shells.

2. The "A" Set (nicknamed "F-1") is a custom fade between Ferrari Red and Williams F1 Yellow airbrushed "Little Blokes" on the shells (this is a stylized version of Nigel's trademark signature drawing he does with his autograph).

3. The "B" Set (nicknamed "Annette") is a custom fade between Breast Cancer Pink and Williams F1 Yellow with airbrushed "Little Blokes" on all the shells (also a stylized version of Nigel's trademark signature autograph drawing).

2x DW 18x22'' kick drums

2x DW 8x22'' woofers

DW 7x8'' rack tom

DW 8x10'' rack tom

DW 10x12'' rack tom

DW 14x16'' floor tom

DW 16x16'' floor tom

DW 5.5x14'' snare drum

All DW hardware and DW5000 pedals

Vic Firth drumsticks (signature model based on the "Rock" stick)

Remo drumheads (Clear P-3 on kick, Coated Ambassador tops and Smooth White Ambassador bottoms on the toms)

Paiste 2002 24'' ride with 24 Rivets

Paiste signature 20'' Mellow ride or Silver Mellow ride

Paiste signature 18'' Full crash

Paiste signature 14'' Power hi-hats

Special thanks to Johnny Barbis, Chris Sobchak and Steve Lehrhoff

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

“Tonight is for Clem and it’s for friendship. An amazing man and a friend of the lads”: Sex Pistols dedicate Sydney show to Clem Burke

“Almost a lifetime ago, a few Burnage lads got together and created something special. Something that time can’t out date”: Original Oasis drummer Tony McCarroll pens a wistful message out to his old bandmates