Drummer-composer Antonio Sanchez talks Birdman

Alejandro González Iñárritu's Oscar-nominated Birdman – the feverishly unhinged and darkly comic tale of Riggan Thomsen (Michael Keaton), a one-time Hollywood action hero looking for a Broadway comeback – rewrites a lot of cinematic rules, as does its head-turning score. Using just drums and cymbals, four-time Grammy winner and newbie film composer Antonio Sanchez plunges us into both Thomsen's inner (and outer) turmoil and his surrealistic flights of fancy.

“I don’t know if we were consciously thinking about something that was groundbreaking," Sanchez says. "You always want to try to do something new; nobody’s interested in repeating tried and true themes and forms. I have to give the credit to Alejandro for imagining that such a score could actually work. How he thought up a movie could go with that music is absolute genius. Luckily for me, I was the one chosen to perform it."

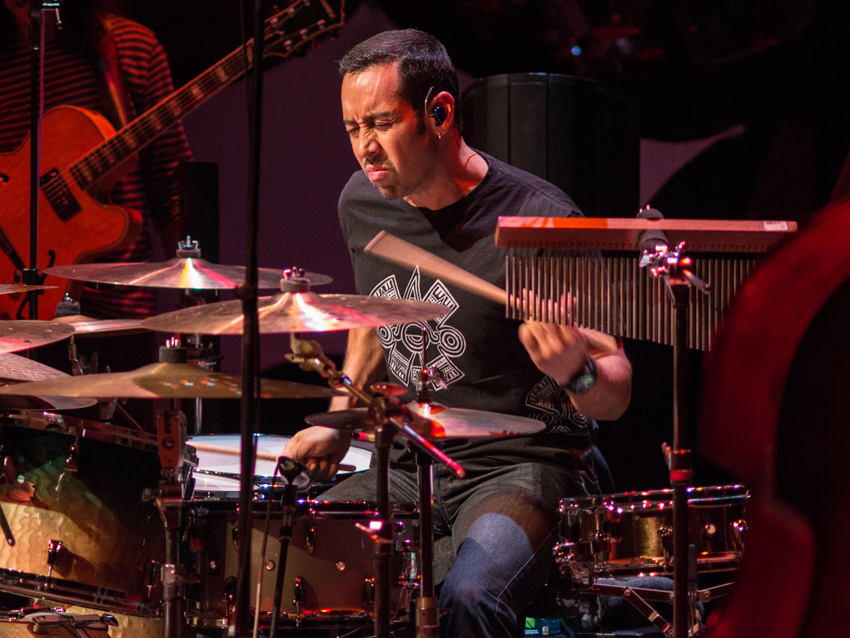

Sanchez is no stranger to jazz aficiandos: Since 2002 he's been a member of the Pat Metheny Group, and his resume also includes recordings by Chick Corea, Gary Burton and Michael Brecker, among others. In addition, he leads his own band, Migration, which will issue an adventurous hour-long piece, Meridian Suite, later this year. Birdman is, of course, exposing Sanchez's work to a new and wider audience, and during a recent afternoon the drummer-composer sat down with MusicRadar to talk about how his involvement with the film came together.

Why did Alejandro think that having the drums as the primary sound source for the score would work?

“He thought that because the film is a comedy, in essence, and because comedy requires rhythm, that drums would be the perfect way to achieve that goal. Also, I think it was because of the way he wanted to shoot, with the long shots around the corridors of the theater. The forward motion of what the drums could provide was what he was looking for.

“Plus, he wanted something that wouldn’t cater to an audience’s expectations. That’s something that’s always bothered me about a lot of scores, the way you’re spoonfed everything you’re supposed to feel at every moment. Drums are a little more abstract in that way."

People don’t usually think that drums can evoke moods and express feelings like other instruments. You prove otherwise with Birdman.

“That’s true – people don’t think of the drums in that way. I think they're a very untapped resource. Anytime you hear percussion in a film score, it’s usually part of a larger orchestral score. And I do love that kind of thing, but I think drums and percussion are highly underrated sources for evoking and producing different sets of emotions. There’s a very wide range to what drums can do, but you don’t always get a chance to hear it.

“The piano is very good for evoking feelings, but you can’t really change the instrument’s sound. A piano is a piano. A drum set, on the other hand, is so customize-able. You can have three drums or you can have 10. You can have two cymbals or you can have 20. You can hit drums with your hands, with sticks, with brushes, branches – anything you want. We tried a bunch of different things in Birdman to see what would work.”

Note: Video NSFW

The process

Above photo: Michael Keaton and Edward Norton in Birdman

I’m guessing that you didn’t use other film scores as references for Birdman – it’s so different from anything that’s been done before.

“I kind of went my own way. In the beginning, there wasn’t much to look at for reference. I really thought it was best to just try my hand and follow my instincts. In the beginning, I tried to come up with rhythmic themes that were very specific for Riggan Thomson’s character or comedic elements, and there were certain things that Alejandro asked me to consider in the first stage of the demo process. But when I sent him the demos, he thought they were a little stiff and pre-programmed – predictable. That’s when I realized he wanted something very organic and visceral. The key to making it work was having me react to the images or working off Alejandro as he described the scenes.”

Were you at first working from the script?

“Yeah. He sent me the script, but to be honest, I didn’t know what to think at first. The thing about scripts – I’ve read a few, not many – is that there’s a lot of subtext that isn’t there. Unlike a book, where things are explained in great detail, you have to fill in a lot of blanks with a script. I didn’t know what things would look like or feel like, so when they started shooting I went to the set to get the vibe. That helped me tremendously. Seeing Michael Keaton in action and picking up on the energy of the film gave me a real sense of what could work.”

Did you then look at rushes to change what you’d done from the original demos?

“No, what happened was, Alejandro and I went out to dinner while he was shooting. We talked about where everything was going, and then we went to a studio in New York and kind of laid things out there. I was at my drums while he described scenes – he went into great detail. With him right in front of me, he’d give me visual cues whenever he saw the scene changing from one sequence to the next.

“We must have done 60 or 70 takes of me just improvising things to what Alejandro described to me. He’d say, ‘In this scene, Riggan is in his dressing room. He gets up and opens the door, and then he walks down this long hallway, turns around and goes to the stage door.' I jammed to all of the movements and directions.”

That sounds like it could be both mad and thrilling, but also scary and strange.

“Oh, yeah, it was all of that. [Laughs] My feelings were 'This is either going to be amazing or it's gonna suck.' There was no in-between to what we were doing. It was either total success or complete failure. But knowing Alejandro and knowing what a creative guy he is, my gut was, ultimately, that it was gonna be awesome. But sure, there’s always that fear: ‘OK, we’re trying something cool, but it might not come together in the end.’”

Sculpting the drum sound

You and Alejandro go back a bit. The Birdman experience wasn’t the first time you two had met.

“That’s true. My story with Alejandro is interesting because he used to be one of the DJs I followed the most back in Mexico City. He worked at a radio station, and I’d listen to his morning and night shows pretty much every day. Whenever I was in my car, I would listen to WFM 96.9. They played the hippest stuff in Mexico, and I discovered a lot of stuff from it.

“What’s funny is, one of the bands I discovered was the Pat Metheny Group. So there I am, years later, playing with that group. Alejandro came to one of our shows in LA, and we met and hit it off just beautifully. We started a communication; every time I’d go to LA, I’d call him up and he would come to my gigs. Or whenever he had a screening in New York, I’d go to one. Then one day out of the blue, he called me up and asked me if I wanted to do this project. It was totally unexpected and very cool.”

What kind of kit did you use for recording the score? Did you alter the drums in any way?

“I always have my main kit ready to go – Yamaha drums and Zildjian cymbals. Everything is always tuned nicely, and we mike the kit so that you can get every detail. After we recorded the demos, they spliced them up and superimposed them over the rough cut of the film, and they saw what worked and what didn’t. Then we went back to LA and redid everything while looking at the rough.

“Yamaha is based in LA, so they brought in a really beautiful kit. I started tweaking it to make it sound dirtier and greasier, not so perfect – Alejandro didn’t like how pristine things sounded on the first demos. His reasoning was, this happens in the bowels of a Broadway theater, so the drums should sound old and beat up. And it worked especially well for portraying Riggan Thomsen’s state of mind. We needed a crazier vibe.”

The point of contention for your ineligibility for an Oscar nomination is that too much classical music was used. Was that always the idea, to weave in Mahler and Tchaikovsky?

“It was. From the beginning, Alejandro knew that he would use that music. As far as the Oscar nomination goes, in the beginning it seemed as though it was only a matter of tabulation and accounting of how much original music was used versus licensed music. It seemed that there was more licensed music than original. We did a recount and discovered that there had been a mistake, that it was over 30 minutes of original music and 17 minutes of licensed music. We then thought we were in the clear, so we appealed."

The Oscar snub

“After that, they had a meeting and came back and said that the original score had been diluted. We all wrote letters – ‘Do you really remember more of the classical music than the drums?’ I mean, think about it: If it’s that diluted, how come everybody’s talking about the drums? I think what we did with the drums is more present than what you hear in other films. It’s not like I’m saying my work is better than the others, but I just think it’s ludicrous to be disqualified.

“But you know, people are aware of it. Public opinion is on our side. If I were nominated, I don’t think I would win. I say that because there’s a lot of stuff behind the scenes going on that has nothing to do with how good something is. You never know, though: Maybe by being disqualified I could’ve won. [Laughs] Things are funny that way.”

Has Birdman opened other doors for you? Have you gotten calls about doing other scores?

“Yeah, there’s been a few calls about doing some other stuff. We’ll see. If I do anything else, I want it to be as cool as Birdman. I don’t know if something like that will ever come along again. I’m not a film composer; I have a very fulfilling life as a musician, as a leader, writing music for my own projects, so we’ll have to see what else works for me. It has to be the right thing. To give a few months of my life to something, I would want to do something really cool.”

As far as your own music goes, what do you have coming up?

"I’ve got a couple of solo albums coming out. The first is called Three Times Three, and the other is The Meridian Suite. Three Times Three is an all-star project with three different trios. One is Brad Mehldau and Matt Brewer, one is John Scofield and Christian McBride, and then there’s Joe Lovano and John Patitucci. So it’s three tunes with each trio. The Meridian Suite is one hour-long composition, and that’s me with my regular band, Migration. Compositionally and conceptually, it’s my most ambitious project. I’m really looking forward to people checking it out. It's a cool time for me – lots of great stuff happening."

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.