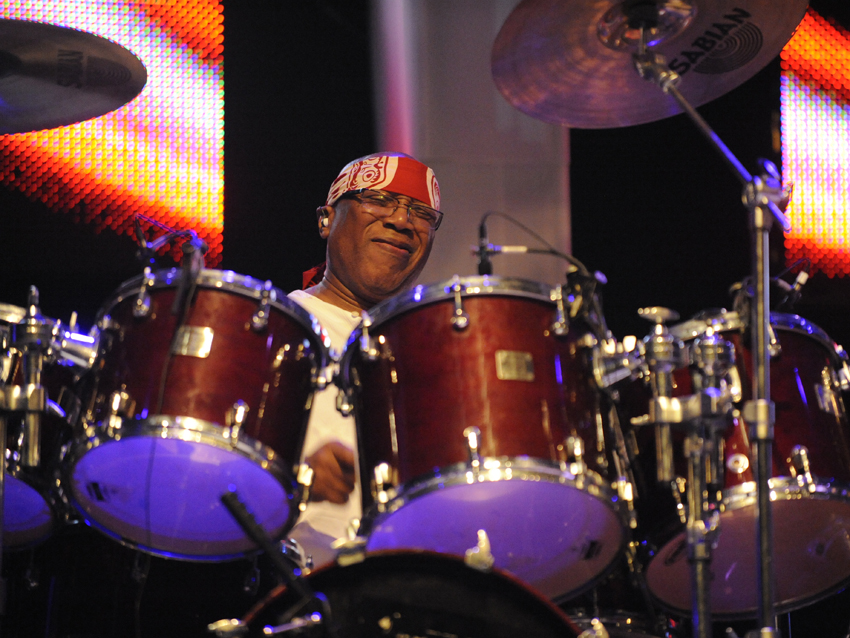

Billy Cobham's top 5 tips for drummers

For over four decades now, drummers have focused on Billy Cobham's playing in much the way that a cat eyes a mouse – with rapt, laser beam-like intensity. But the fusion legend is the first to say that music is a communal effort, and if the whole band isn't working together as one, whatever skills he brings to the table are of little consequence.

“Sometimes you have individuals who are outstanding technical players, but they don't know how to function within a group." Cobham says. "People practice on their own for years and years, but when they get into a room with other musicians, they can be lost, and that's when the musical message is lost to an audience."

With that in mind, Cobham is launching the Art Of The Rhythm Section Retreat, a seven-day (August 4-10) immersive experience at the Chateau Resort Bechyne in the Czech Republic geared toward helping musicians better understand the basics of teamwork and collaboration. “The focus is on teamwork and multi-tasking," Cobham says, "getting people into working together to make a stronger foundation for playing music as a unit."

Breaking it down further, he explains, “You have your typical situation of a guitar, keyboard, drums and bass. You walk into a room with a bunch of people who have never played together before. Where do you start? How do you open up the conversation through your instruments and continue the dialogue through music? There are different ways to go about it, and that’s what I want to concentrate on."

Observing other musicians is key, Cobham notes – something he's put into practice in his own approach to playing. “I like to work with my colleagues and see what they’re all about, not just what they do best but what they don’t do well," he says. "Sometimes that’s where the rest mysteries are hidden. Also, I encounter a lot of competition in rhythm sections, so I like to look for ways for that energy to be channeled in positive ways that result in more creatively. That’s how you build a musical foundation that’s based around mutual respect.”

Joining Cobham in The Art Of The Rhythm Section Retreat will be members of his Spectrum 40 band as lead faculty: guitarist Dean Brown, bassist Ric Fierabracci and keyboardist Gary Husband. For more information on Billy Cobham's The Art Of The Rhythm Section Retreat and to sign up, visit the official website.

On the following pages, Cobham runs down his Top 5 Tips For Drummers.

Watch your posture

“Think about your posture and learn how to adjust your drums with authority and respect. Don’t just sit down at the drum set improperly; if you don’t sit comfortably at the drums, the drums will know.

“Drums can’t play themselves; you have to play them. But if you’re not comfortable, the people listening to you won’t be comfortable either, because everything is off. An audience can feel that something is wrong. They know when something isn’t happening, even if it’s something they can’t identify like, ‘Oh, he’s sitting wrong.’

“Music is a very mystical platform, and if you’re not in control of what you have to say on that level, it comes right across to everybody – and not always in the way you hope it will. So sit at the drums with respect and present your ideas, and from there you’re off.”

Focus on weaknesses

“For some reason, people don’t do this – they only concentrate on their strengths. With drums – and with all music period – 99 percent of the time it’s ‘Hey, Mom. Hey, Dad. Look at what I can do. Look at me. Watch me.’ You play all the stuff you’ve got down, but you don’t want to show them the things you’re working on. And those are the things you’ll keep on neglecting.

“Or you might think, ‘OK, I know what I need to fix. I’ll woodshed.’ No, no, no – don’t do it privately. The best place to work it out is on stage. Get in front of people and present that idea you’re trying to put across, even if you don’t have it yet. It might sound like a mistake, but so what? Get past it.

“Insecurity is the enemy to musicians. But if you’re not afraid to show people who you really are – the yin and the yang and everything in-between – then you’re going to be a very genuine musician. Share yourself, your whole self. If you do, you’re going to be a complete musician.”

Learn to play synchronously

“Use your feet as well as your hands. That’s not easy – that’s multi-tasking. You have to sit down and start slowly, and you can’t get fed up and slide back to old habits. It’s not about crawling; it’s crawling on all four limbs while the brain is listening to everything.

“You have to figure out which hand is going to move forward in relationship to which foot – and why. And you have to realize how you want that to come back to you in real time.

“You’re committing to a lifestyle. It becomes part of your soul and your family. But these are the things you have to do at the drop of a hat, until you don’t have to think about what you're doing and it all becomes totally natural. It all comes from patience and application.”

Play musically, not competitively

“We go back to it again: You’re presenting an idea that you’re contributing to the overall band picture. You want to make sure that it’s something the band can live with in real time.

“Sometimes it’s the simplest thing, and you might think, 'Aw, man, I’m so tired of doing this.’ But that’s the thing you can control the best. If you play it long enough, everybody will start to groove to it, and suddenly you’re making music together. Once you start from that place, then you can add more to it and build on it.

“If people are trying to simply impress you with your chops, that’s when music becomes work. I might as well quit what I’m doing and become a postman, because then it’s ‘How many letters can I cram into a mailbox?’ I don’t want to compete with my colleagues; I want to contribute and help them build their musical ideas – and vice versa. Then we have this loop of knowledge and ideas to build a strong, exciting foundation and a communal presentation.”

Coordinate patterns seamlessly

“Drummers tend to play one pattern into the next as if it's all written in a book: ‘OK, here’s pattern one, here’s pattern two,’ and so on. And you can hear them moving very mechanically from part to part, thing to thing, but it feels very stiff and disjointed. That’s not music to me.

“Another problem with that is, drummers can never really play something again – because they never learned how to play it the first time. It’s as if they stumbled upon what they did, but they don’t know what it is. Somebody might say, ‘Wow, that was good. Can you do it again but softer?’ And they can’t because they didn’t get inside the music.

“Stop thinking of music as parts; think of it as music. A song or a piece of music isn’t lots of little patterns or sections – it’s a complete experience. Think of what it is you’re trying to put across, the whole thing.”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

“Tonight is for Clem and it’s for friendship. An amazing man and a friend of the lads”: Sex Pistols dedicate Sydney show to Clem Burke

“Almost a lifetime ago, a few Burnage lads got together and created something special. Something that time can’t out date”: Original Oasis drummer Tony McCarroll pens a wistful message out to his old bandmates

“Tonight is for Clem and it’s for friendship. An amazing man and a friend of the lads”: Sex Pistols dedicate Sydney show to Clem Burke

“Almost a lifetime ago, a few Burnage lads got together and created something special. Something that time can’t out date”: Original Oasis drummer Tony McCarroll pens a wistful message out to his old bandmates