Billy Cobham picks 10 essential drum recordings

Kenny Aronoff calls him "a total fucking genius." Glen Sobel says he's "a monster. His playing is so ahead of its time." And Rod Morgenstein, reflecting on the impact that Billy Cobham's drumming on the Mahavishnu Orchestra's 1971 album, Inner Mounting Flame, had on him, says that he "wore out the grooves on every part of this record trying to figure out what Billy was doing."

So it would appear that a rising chorus of top drummers' voices is building to something of a consensus – that jazz-fusion pioneer Billy Cobham is the ultimate.

Informed of the huzzahs and hosannahs thrown his way, Cobham chuckles, appearing flummoxed for a second, finally saying, "Yeah, well... OK then."

MusicRadar sat down with the fusion legend to turn the question around, asking him to assemble his own list of personal favorites and essential drum recordings. Cobham was happy to oblige, although admitting that his choices are of a certain vintage. "I’m listening to the old school," he says. "I’m sure there are geniuses out there who I’m blowing over. But when you think about people who really did something great on the drums, it’s like watching a pitcher like [New York Yankees great] Mariano Rivera: Even in his twilight years, it’s like, ‘C’mon. Where do you go?’ And the answer is, you go back."

For Cobham, a memorable drum recording has little to do with technique and everything to do with personality. He cites big-band great Mew Lewis as somebody who "always made you aware of the guy he was behind the kit. He sounded like the most musical garbage can player around. His fills reminded me of somebody taking out the trash. It was crazy, but it worked."

Cobham, who has just begun US dates as part of his Spectrum 40 Tour, pays his respects to Lewis and nine other star stickemen on the following pages.

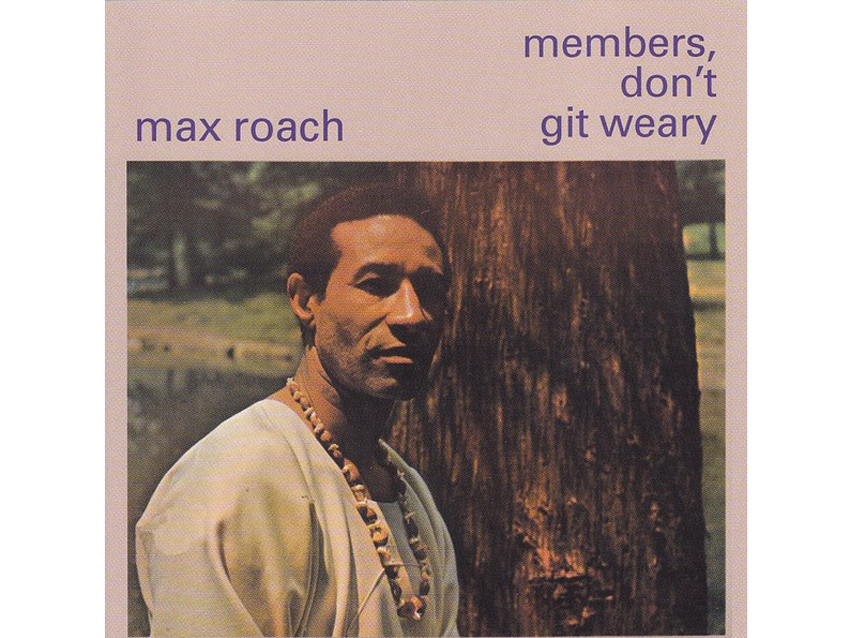

Max Roach - Members Don't Git Weary (1968)

“It was a major statement, and when it came out in the ‘60s, it was a very sensitive time as far as the race question being presented. You have to remember, over the last 20 or 30 years, on islands like Guadalupe, people weren’t allowed to play their own music – they might be put in prison. So the statement being made by Max and the group of musicians he played with at the time was, they wanted to draw attention to themselves and the wrongs that were being presented to them. They did it through their art.

“That tells me a lot about the power of music. Even today, not just in Guadalupe, but it’s reflected in Iran and Afghanistan, they want to shut the door – and in some cases, the Taliban has shut the door on music. You play music, you die.

“To me, Members Don’t Git Weary falls into the category of being a major sonic statement.”

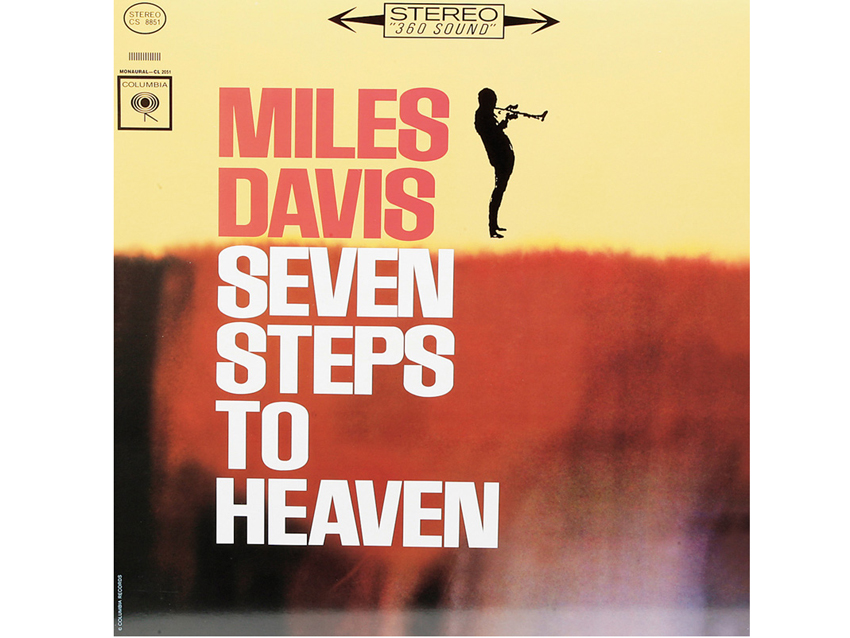

Miles Davis - Seven Steps To Heaven (1963)

“Tony Williams, my contemporary. He’s maybe one or two years younger than me, but man, he was doing things that really inspired me. Just the musical side of it was great. As far as his personality goes, he might have done things another way. But that was Tony – Tony was Tony. [Laughs]

“In a way, now I love him even more for it. He took his position, and he did whatever he had to do to get over. I didn’t agree with him playing so aggressively and at levels of volume that I found unnecessary, but on the other hand, that’s like telling Terry Bozzio, ‘Don’t play so many drums.’

“Everybody has his way, and Tony taught me a lot by his actions. Through music, he does not lie. If you feel a certain way, that’s what you’re going to play. Tony made this record when he was 18 or 19 years old, and he was already such a talent. It blew me away. I saw him at a festival and I told him, ‘You just opened it up for me a lot of other cats.’ Not that we were going to play with Miles, but we could play with people like Miles.”

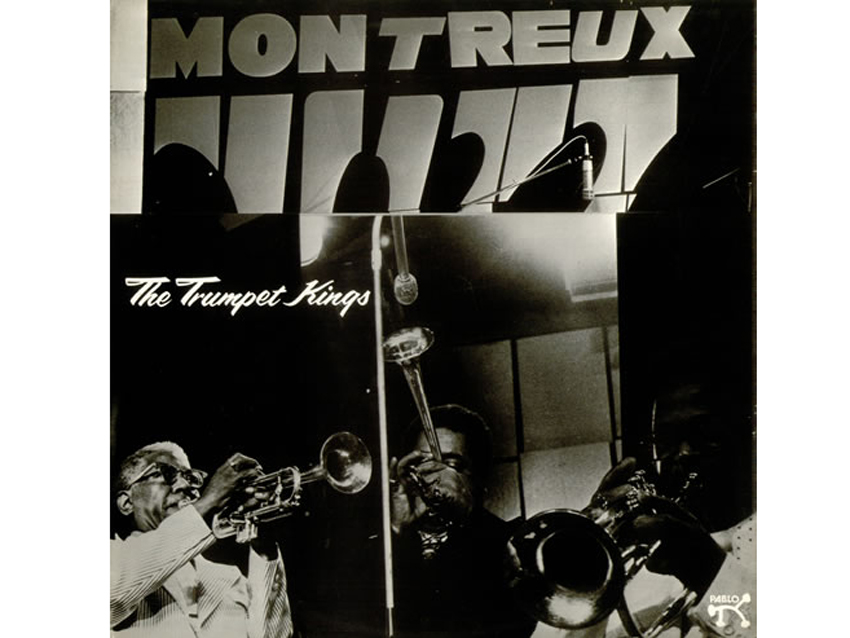

The Trumpet Kings At Montreux (1975)

“Louis Bellson is in the rhythm section with OP [Oscar Peterson], backing up all of these trumpet players. He was one of the big-band drummers who could also play in a trio, and he did it on the same, exact set of drums his whole life. He knew how to feather things so musically.

“One of his dimensions that made a big impression on me was how he composed for everybody else. Here’s a percussionist writing for other musicians as a percussionist would envision them playing. That’s what I do, and I learned it from Lou, just like I learned playing with four sticks and playing with multiple bass drums and all kinds of things. It all came from Lou. He’s got a very special place in my heart.”

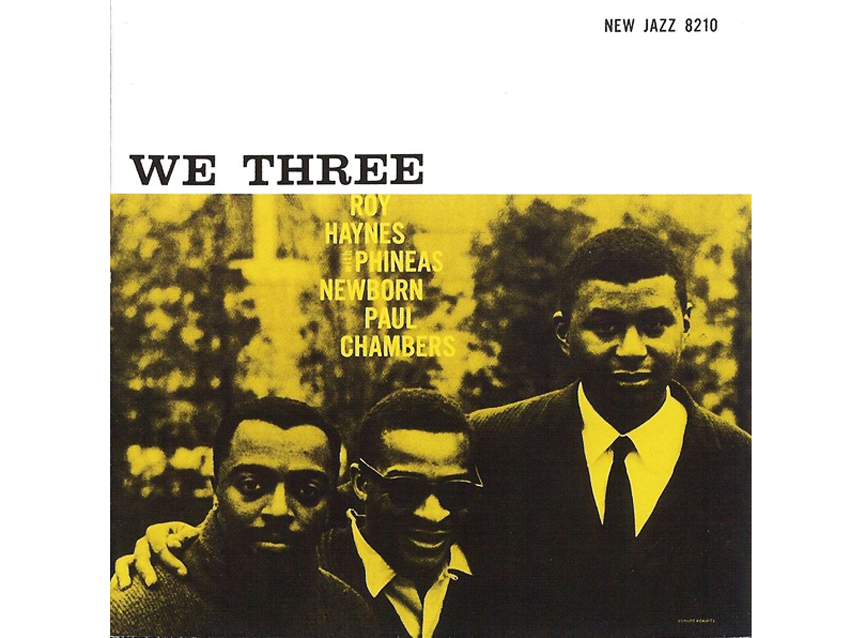

Roy Haynes, Phineas Newborn, Paul Chambers - We Three (1958)

“Roy is kind of like my uncle. We go way back. His nephew was a co-leader of band with me and some other guys. We had a band at the Music and Art High School in New York. Roy used to come by when we were practicing in this basement, and he would advise us. To be that young and be so close to somebody like that, it was wonderful. He was turning mud into diamonds.

“That's the sort of thing that stays with you, having experiences where you go, ‘OK, this is how it’s done.’ Those are the things that you remember… as well as records like this.”

Buddy Rich - The West Side Story Medley (1966)

John Coltrane - A Love Supreme (1965)

“Elvin Jones’s groove was infectious, and then it became a virus. It became a virus on this record, right as you listened to it. For me, it was monumental. I haven’t listened to A Love Supreme in almost 15 years, but I can still hear Elvin playing it. It was that strong. I can feel [bassist] Jimmy Garrison; I can hear Trane, of course; but Elvin’s right in the middle of that. The treatment of [pianist] McCoy [Tyner] is unbelievable.

“When you put that whole band together, and you listen to what Elvin is doing – and it’s so uniquely Detroit-Latin – and you realize that nobody, just nobody… no way… [laughs] These are personalities that I do not encounter now.”

Count Basie And His Orchestra - The Atomic Mr. Basie (1958)

“Here we have Sonny Payne, the first guy I ever saw who twirled sticks. [Laughs] He was beyond my understanding. We’re talking 1957, ’58 on the Ed Sullivan Show – it was heavy. He was such a showman. He would come on the bandstand with the big, big band, and all he had was one bass drum, one floor tom, one snare drum, a ride cymbal, a crash cymbal and a hi-hat. That’s it, man.

“Now, picture that setup, and the guy is pushing the Basie band. He pushed them out onto the street, out onto 52nd Street and Broadway. And he did it with intensity, sensitivity and touch. These are things you have to live.”

Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Jazz Orchestra - Central Park North (1969)

“And then you have Mel. Sometimes with the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis band, you had the orchestra up there, all of these things are happening, everybody’s groovin’, and then when it came time for Mel to do a fill, it really did sound as if he put together a garbage can full of stuff, and right as he was taking it outside, the bottom breaks and everything falls out of it. And then he’d come back in on time, and you go, ‘How did he do that?’

“When you sit down at Mel’s drum set, you realize that everything was very loose. The snare had all of these ripples in it. He didn’t play anything tight. If you played his kit, it would probably feel awful. But the thing about Mel was, he chose elements that made up his personality. All of the respect in the world, man.”

Duke Ellington - Duke Ellington's Greatest Hits (1968)

“Check out Sam Woodyard. The blues that was played at the Newport Jazz Festival back in the ‘50s, where they played 26 blues choruses – this was after Duke came out with his classical stuff – but when they did the blues, all of the people who had been walking out came right back. That was Sam. He was there.

“His groove had such a level of intensity. The band was moving him, and he was moving them – it was a mutual agreement. He was part of the whole thing, and he didn’t stand out, but he played his role to the ultimate. You can’t buy that in a store, man.”

Papa Jo Jones - The Everest Years (2005)

“The Foot! Papa Jo could feather a bass drum. He came with his own dance shoe that he used to play on a specific bass drum pedal. So he had the dance shoe, a sock – actually, two, and they were white – and he played this one old Ludwig Speed-King pedal, which had a huge powder puff beater. Many times, Jo would play without a bass player, or if he did, he would edge on the bassist. He played as if he were dancing.

“These are very, very special things. Buddy was a dancer, Tony was a dancer, Louis was a dancer, and Papa Jo was a dancer. That’s some school.”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

“I oversaw every element - not just the music and the lyrics and the melodies and the production, but also the merch and the fan clubs and everything”: Mike Portnoy talks about his years away from Dream Theater

“I’m surprised and saddened anyone would have an issue with my performance that night”: Zak Starkey explains why he got fired from The Who

“I oversaw every element - not just the music and the lyrics and the melodies and the production, but also the merch and the fan clubs and everything”: Mike Portnoy talks about his years away from Dream Theater

“I’m surprised and saddened anyone would have an issue with my performance that night”: Zak Starkey explains why he got fired from The Who