10 popular drum questions answered by our experts

Taming snare buzz, tuning resonant heads and more

10 popular drum questions answered

DRUM EXPO 2014: At one stage or another in their career, every drummer will face a gear or playing conundrum that will require time and research to correct. Whether that's unwanted buzz from snare wires, to polishing cymbals or how to get a bigger bass drum sound, these are all worries that get in the way of actually playing, and enjoying, our drums.

To help you get the best results and to clear these hurdles quickly we've rounded up the most popular questions most drummers will ask at some point in their playing lifetime, and roped in our resident gear guru Geoff Nicholls, and a host of his famous friends, to answer them. First up, drum storage...

How should I store my drums?

Simon Jayes of The London Drum Company says, “We store around 120 snare drums in our warehouse. All of the drums are uncased and always set at a rough playing tension. There is really no need to detune anything or slacken anything off. I would suggest that keeping the drums at tension keeps them in shape and less likely to detune when you do take them out and start playing them. We always keep the snare strainers on so that the wires don’t get damaged and remain flat and true on the head.

“There really is only one golden rule for storage of drums and that is to avoid moisture at any cost. Drums can endure extreme temperatures, be it cold or hot. Just make sure that your storage area is dry and ventilated (if possible) and your drums will be perfectly happy. Also, ensure you give them some TLC once every few months – lug lubricant, dust removal, etc.”

What do I need to play my electronic drum kit live?

Simply put, to sound good live, e-kits need serious amplification to the point where the cost, weight and complications of said amplification often outweigh any advantages, certainly on smaller gigs. The humble acoustic kit has a far greater dynamic range than an e-kit and in small rooms needs little or no amplification. Although PA technology has come on in recent years, for most local gigging bands with a small compact PA and tiny monitors, adding an e-kit will severely test its limits.

Since drums have a vast range of extremely punchy dynamics you need special amps designed to handle the broadest frequency spectrum. In fact, to overcome the plastic tea-tray sound you need weighty, active/powered cabinets and ideally a sub-woofer for today’s all-important fat bottom end. You could easily spend between £500 and £1,000.

Yamaha and Roland weigh in with robust drum amps around the £400-£500 mark. These work pretty well for personal monitoring. But many drummers go for PA-style wedge monitors. E-kit expert Simon Edgoose suggests, “I would recommend buying two Mackie SRM450s (or similar), just so you can hear yourself, and use them as a small PA. The trick is to run the speakers on around half power (you need headroom so the speakers aren’t stretched to their limits) to get the best sound. A big speaker run at half volume will sound much better than a smaller speaker run at full volume.”

Should I polish my cymbals?

Aside from sound, there are two other considerations regarding cleaning a cymbal: how safe is the cleaning process and what look do you prefer? Taking the latter first, music is so much about image, reflected in your person and as a member of a particular type of band. Some acts/bands have an ultra clean stage presentation, and that stretches to the musical equipment. Others prefer casual. The grungier and funkier the better. For the latter it’s easy – don’t clean them.

Whether you like them shiny or not, you should at least keep them dry. Damp rehearsal rooms/clubs etc, sweaty fingers and acidic deposits, are a constant threat. Fastidious drummers use soft cotton gloves to pick up cymbals (by their edges), wipe marks off with a soft dry cloth and keep them in protective bags. Modern cymbal bags with woolly linings protect your cymbals and keep them warm and dry.

Still, however careful you are, cymbals will gradually get dirty. They have lathed grooves in which dirt can lodge and dull the sound a little. The argument for and against cleaning therefore actually involves sound. Top UK drummer Steve White says, “I don’t worry too much about cleaning cymbals. I like it when a patina builds up and actually tones down some of that ‘zing’ that a brand new cymbal has. It is all subjective, but if I were to clean any cymbal it would only ever be with warm water and a little washing-up liquid anyway, anything else is too messy or can be abrasive.”

A duller-looking cymbal may actually sound slightly less toppy. And for many, looking for the darker mysterious timbre traditionally associated with very old Zildjians, this is a plus. Older cymbals gain a patina which gives them a slightly mellower sound, sought after by many drummers. Patina is a vague term covering the visual effect of a combination of various chemical compounds on copper and bronze alloys, including oxides, carbonates, sulphides and sulphates. It’s why the Statue of Liberty is green. Unlike rust on iron objects, this milder tarnish (or verdigris) actually protects the copper or bronze from further degradation. It is therefore valued in lots of vintage metal objects like jewellery, and also old cymbals.

The fact companies produce brilliant finish cymbals suggests dazzling platters are attractive to many drummers. Without going into the whys and wherefores, polishing a cymbal to a brilliant finish does not of itself make it brighter sounding – although psychologically it seems reasonable to think that. Regardless, there is a distinction between mild cleansing and vigorous polishing. Expensive cymbals are highly tempered and many have thin protective coatings. Using any scouring substance can cause scratches; power-tool polishing with attendant friction heating can conceivably affect the temper. So whether you clean is down to taste – how you clean is a controversial subject for another day.

How to do I stop my bass drum and hi-hat pedals creeping?

Many bass drum and hi-hat pedals have toe-stops fitted to counteract the problem, but let’s look at possible causes. If your foot is pressing farther forward than you want it to, this could mean you have unwanted tension somewhere in your posture and execution. Having large feet (and being tall) can exacerbate the problem, but the reason more likely lies elsewhere. Something is pushing you forward when you want to hold back. That suggests tension. Is your whole body creeping forward? Ideally the angle of your knee should be a little greater than 90°, ie: your shin/calf should slope slightly forward. This gives you leeway, whether your heel is raised or not, to move up and down the footboard without cramping your leg. But if your whole body creeps forward the angle at your knee can fall below 90° to a tension-inducing acute angle.

The latter is common with nervous tension. The more tense you are the more you will lean or move forward, while the more relaxed you are the more you will sit back – indeed you will be ‘laid back’. If for any reason you are a bit uptight then there is a natural tendency to sit forward, to push. This can affect your whole playing position so that you can find yourself striking your snare drum beyond centre too. Or it may just be your lower leg creeping forward, so the knee angle is getting way greater than 90°. In this case it can be too big an angle for effective power and control.

Either way there are two steps to take. First, video (or at least photograph) yourself playing and study what is going on. Second, examine carefully professional players with good posture.

Why should I put a hole in my bass drum head?

Cutting a hole in the front head increases the attack, shortens the note and reduces resonance. Back in the late-’60s and ’70s drummers removed the front head entirely and used loads of damping to cope with the advent of close miking and multiple mics.

By the ’80s drummers had put the head back on, but cut a porthole. Today some drummers are finally getting back to using full front heads…

Also going back to the ’70s, the rock legends like Cozy Powell played shallower 14" deep bass drums with larger diameters, ie 24" or 26". Today’s drummers wonder why they can’t get the sound of a 26"x14" out of a 22"x18" (or even 20"x20"). You will get a deep sound, but it won’t have the slam of a 14" drum.

Deep Purple’s Ian Paice adds: “there are many points to take into account with bass drum tuning, damping and miking. First, the only time you cut a hole in the front head is for using a microphone. Acoustically, a bass drum sounds best with two complete heads. This gives depth, duration of note and warmth – which the microphone really doesn’t like! Personally, I love the ‘old school’ sound of a bass drum (with complete heads), but I do understand that in modern amplified music it often will not work as well as a ‘doctored’, miked-up drum.

“The size of the bass drum is important too. Smaller drums – 20" or 22" – are easier to control as they work at a higher frequency than larger drums. For miking a smaller-sized kick with a porthole, and fitted with a sound control batter head like a Remo Powerstroke, detune the heads to the point just before they start to look wrinkled. This will give a powerful, punchy sound. It’s helpful (and for me absolutely necessary) to have good monitors that allow you to hear the bass drum correctly, as most of the acoustic volume of the drum will have been eliminated to accommodate using the microphone.

“Bigger drums have their own problems, but when you get it right they give you a more satisfying and, when needed, more devastating sound. You have to use more internal muffling to eradicate the overtones and subsonic notes inherent in the drum, and I have never really found a method that works perfectly for every drum. The bass drum beater is important too: if the beater is soft you lose impact, if hard you lose depth.

“Many of us are now moving back to shallower drums, the theory being that the closer the heads are to each other, the faster the front head reacts to the beater note. My stage kits have a 26"x14" kick, and I use 24"x14" in the studio. On our last record, Now What?!, I used a 24"x14" with both heads intact and achieved what I think is the best sound I have ever recorded. Remember, if you get the drum to sound good to your ears, it will probably mike up pretty well.”

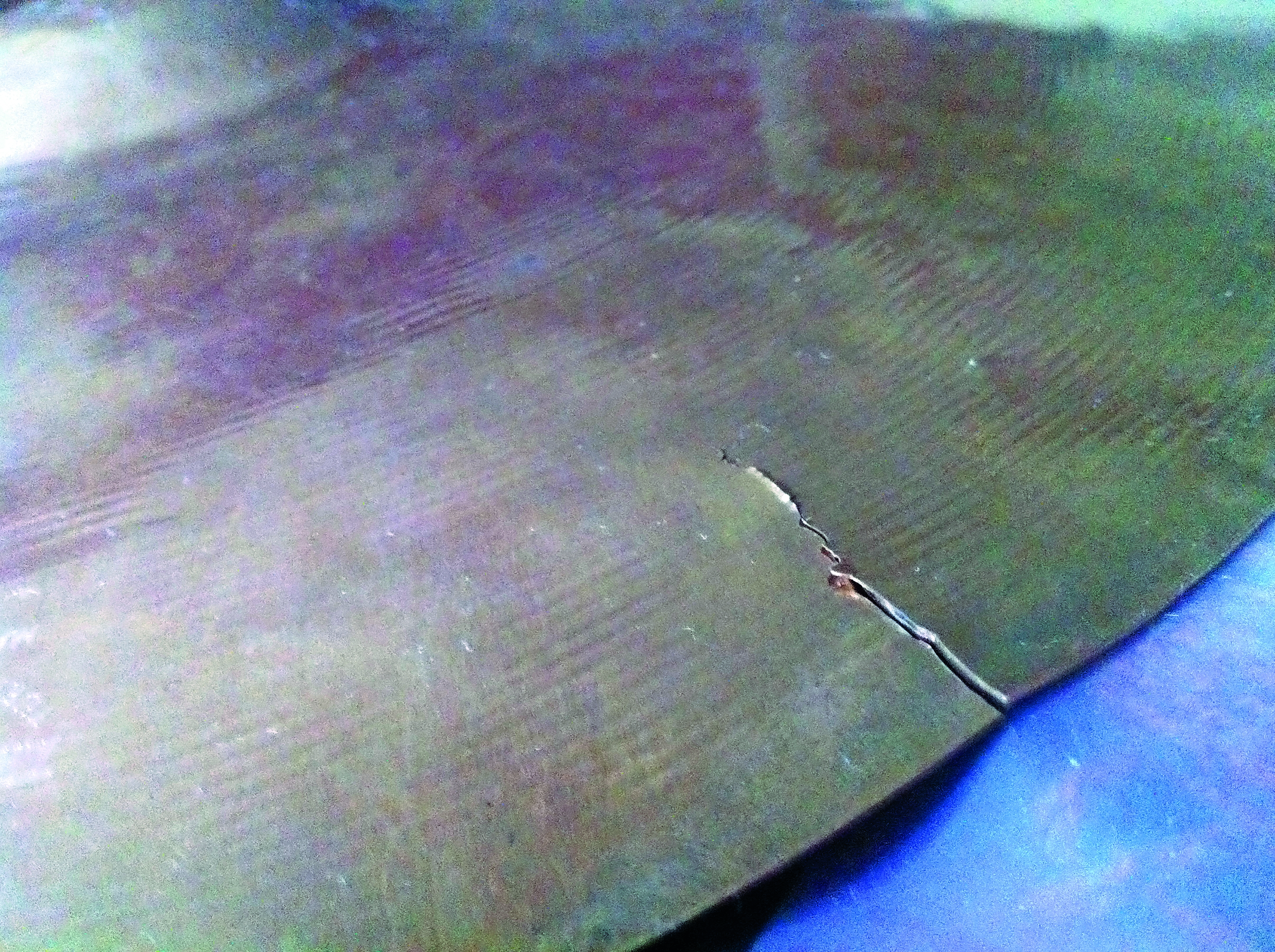

Can I fix my broken cymbals?

If you continue to play a cracked cymbal then it is liable to go on getting bigger and bigger until the cymbal becomes completely useless. How long the cymbal might last is impossible to tell, but in the meantime you will have a cymbal that produces an unusual trashy sound.

It is possible to rescue a cracked cymbal, after which it may last for years. This involves some basic metal work, which you should only attempt if you feel qualified to do so. Alternatively, hunt down a specialist online. The time-honoured solution which drummers have been employing for decades with varying degrees of success is simply to drill a small hole at the end of the crack, using a top quality metal drill bit (maybe 1/8th" or 3/16th"). The idea is that the rounded (and file-smoothed) edge of the hole will prevent the crack from progressing.

The cymbal needs to be clamped and full protection for hands and eyes, etc worn. Masking or gaffer tape can be applied to stop the drill bit from slipping. Try not to apply pressure but just let the tool do the work. The problem with this is that you will still have the jagged tear, but it may be possible to file this down to a smooth, non-jagging and vibrating slot. An exposed slot though is likely to crack again if you inadvertently strike near it. So it’s as easy and usually better to cut out the whole area around the crack.

This is done by sawing or grinding a smooth rounded-edge scallop around, and a little way beyond, the existing crack. You are left with a rounded ‘U’ cut in the cymbal’s edge and this should be smoothed out using a fine metal file and sanding.

In order to minimise the possibility of breaking any more cymbals, check the way that you play. Edge cracks usually occur with crash cymbals because they are smashed with some force using the shoulder of the stick. To minimise the shock effect on the cymbal metal, angle your cymbals a little towards you, ie: don’t mount them horizontally, so you don’t hit them edge-on.

Strike with a glancing blow, almost away from the cymbal, not into it. That will also give you the fullest tone. Don’t over-hit as there is no point beyond the maximum volume of the cymbal. Also, make sure your mounting felts and centre sleeves are always in good nick so there is no metal-to-metal contact. And don’t over-tighten the wing nut – allow the cymbal to sway loosely.

How should I tune my resonant heads?

Resonant heads are so-called because they maximise the resonance of your sound when tensioned sympathetically in relation to your batters. You hear it said the batter is for feel and attack while the reso is for projection, tone and sustain. It’s natural to tension your top head so it feels great where you are sitting, so it can be a shock when you go out front and listen to someone else playing your drums and they sound dull. This is often the result of resonant head neglect!

Start by removing both heads from your small tom and wipe round the bearing edges. If you can afford it, buy new heads. The easiest option is to have the same type of head on the bottom as on the top. Try a single-ply Coated or Clear Remo Ambassador, Evans G1 or Aquarian Classic/Coated. If you prefer harder wearing double-ply batters (Remo Emperors, Pinstripes or Evans G2s), it’s still usual to have a single-ply resonant for better sustain and brightness.

Now you are faced with three tuning options: resonant head the same tension as the batter; or higher or lower than the batter. Tune top and bottom the same for maximum clean, open tone; resonant head lower for a funky, wet, dipping sound (but beware, this can be heard as dull out front). Or slightly higher for a little extra spark. Some like the batter medium for a fat feel but with enough tension for good stick bounce, and the bottom the same or a little higher to brighten the effect, especially if un-miked.

Try starting with the bottom head, then seat the batter and experiment with the three options. There is no substitute for just doing it… a lot. Guitarists have to tune every time they play. Drummers may leave tuning for weeks, months, years!

Top session drummer Ralph Salmins adds: “I usually derive more pitch from the bottom head. Once the heads are seated, I try to get both approximately the same pitch, whether tuning high or low. This gives a clean, resonant decay. Try to find the pitch of the drum that seems most natural; I find this is often not too high but closer to the bottom end of the tuning range. I prefer a Clear Ambassador resonant and Coated Ambassador batter. I use Coated Emperors on floor toms for a little extra fatness.

“I take the drums off their mounts and tune the bottom heads if I’m not getting the sound I want. A pain, but it has to be done – this really affects the whole sound. I only change bottom heads when they are worn out… every few years probably. Fresh ones always make a difference of course.”

What's the best way to tame snare buzz?

All drummers, even the mighty Portnoy and Lang, experience snare buzz. It’s in the nature and physical construction of a snare drum that the snares will respond sympathetically to extraneous frequencies at some point. And it’s often an adjacent, similarly-sized tom that sets them off. A small adjustment in tom tension, or maybe slightly tightening the tension bolts on either side of the snare wires can often alleviate the problem. The fact that you can’t hear sympathetic buzzing on the recordings of Portnoy or Lang does not mean they never have to contend with it.

There are, however, techniques when recording/miking to subdue unwelcome noises and Thomas and Mike have some advice on how they deal with or disguise snare buzz. Thomas says, “Most of my recordings are closed-mic mixes of the kit and each drum is miked and controlled/EQ’ed/compressed/gated individually. That usually eliminates snare buzz from the mix.”

And Mike says, “A big reason you don’t hear too much buzzing live or in the studio with me is that I prefer to use more of my top mic – for crack and attack – than my bottom mic (which is more snarey) in my mixes and drum sound.”

Tuning and damping are obviously crucial though and Mike adds, “Duct tape on the heads (both snare and toms) helps control excess buzzing as well.”

There is though another angle on all this. “For me, snare buzz is not unwanted noise,” argues Thomas, “It is ‘sympathetic ring’ that is important for the overall drum sound. It adds a tiny bit of top-end and sustain to pretty much all toms and the kick drum.

“Snare buzz depends very much on the tuning of ALL the drums, as well as on the room/environment and on the type of wires and strainer you use. I personally like the buzz and miss it when it’s not there. Without the buzz, the drums feel more like a bunch of individual instruments rather than a ‘set’. There is a limit to the amount of buzz I can work with, but in case of too much buzz I will adjust the tuning and possibly angle of the tom, rather than the tension of the wires.

“I like to think of the buzz as the ‘glue’ that binds the individual components of the kit together. Maybe looking at it that way makes it a little more enjoyable! If you just can’t fall in love with it, experiment with the tuning of your snare bottom head and snare strainer tension. There are dozens of different snares (24s, 12s, 16s, some with gaps, copper wires, strings, etc) and each has a slightly different sound, response and amount of buzz. There’s the perfect buzz for each one of us!”

What's the secret to a low, boomy bass drum sound?

The biggest, boomiest bass drums are those enormous orchestral or marching band drums which have 26" to 36" diameters but are often shallow, just 10" to 16". They are designed to project acoustically, they are not damped, and they have large diameters because the larger the diameter the deeper the fundamental tone. Conversely, much of what has happened over the decades with kit drums has to do with controlling the boom, particularly since drummers started to use close miking.

Cutting a hole in the front head, putting damping inside and using heads which have damping elements built-in, or are double-ply – all these reduce the boom and help control the sound. As you found yourself with the heavily-damped Aquarian SuperKick, this is a great head if you want a tight, thuddy thwack. It’s funky but it’s not that boomy.

A port hole increases the punch, but decreases the boom, by allowing the sound/airwave to dissipate forward. The bigger the hole the tighter the drum but the less reverberant the shell will be. Damping (of the heads or the shell) inhibits high-end frequencies and makes the drum sound superficially deeper.

So for boom everything points to single-ply heads, both intact, plus a large diameter drum with a shallow depth. Now hang on, isn’t that the formula followed by John Bonham and Buddy Rich, both of whom played 26"x14"

bass drums? That is, the old big band size, designed to project acoustically before the days of close miking.

Close-miking complicates the picture because it can be difficult for a microphone to handle a booming bass drum at point-blank range. But that is another question for another time…

Back to the initial question: when you said “cannon” and “boom” I immediately thought of Simon Phillips. Simon is not only one of the world’s great drummers, he is a top class engineer and producer. He says: “I would recommend using a Remo Clear Ambassador front and back. Use no damping, tune them both the same, up higher than you would normally and start there. Obviously the size of the shell will make a huge difference. However if the shell is too deep (deeper than 16") then it is not going to sound great. For this kind of tuning a 14"-deep shell is best in my opinion. If it is too boomy then you can experiment with some damping on both front and back heads. Also experiment with having the front head higher and the batter looser. There are so many ways a bass drum can sound and all be viable – it’s up to you what you prefer and, more importantly, how it suits the music you are playing.”

What's the difference between wooden, steel and synthetic drum shells?

We make a big thing out of shell material because that is overwhelmingly what gives a drum its visual identity and it’s natural therefore to assume that it confers on the drum its sonic identity too. Actually the big determinants of sound are shell size, head choice and tuning. When it comes to shell materials we enter a whole other area of speculation and personal opinion as it’s more about subtle flavour or timbre and each drummer hears that in their own way. You regularly hear respected drummers contradict one another when describing metal or Plexiglas, even maple or birch. You might like Brie and I might like Camembert – but how do you describe the difference in taste? And would everybody agree? I find there is little consensus.

Carl Palmer, who has explored different drum materials more than just about anybody, says, “for me the problem with wood has been this ‘cosy’, warm, almost passionate sound! Great for jazz/big band and some types of rock. Because many species of wood are used this argument does not always apply. For example, I have a Brady set in Jarrah ply, the best wooden drums I have ever played. The sound is full, loud, deep and clear. Jarrah can sustain 1,800 psi (pounds per square inch) of shell pressure. Tuning is very good in the low register but gets harder in the high area, say a 12"x8" tom. To get the top end clear and bright you may need a thinner-gauge head, say an Ambassador rather than an Emperor. This wood offers very good sound projection on all levels – only the head configuration needs to be considered to gain a wide range of tuning. This cannot be said for lots of other woods that are still being used to manufacture drums.”

“Stainless steel is my personal favourite,” continues Carl, “because the sound projection in most conditions is extremely good – clear, loud and fast response. Great for prog rock! The top-end brightness is very good and the sound seems to pass through the shell very quickly – there is no [wood] grain, vertical or horizontal, to deal with. So you have an added advantage when playing the toms in any detailed way, as toms always respond slower.

“Stainless steel comes into its own regarding tom projection overall. Tuning is absolutely perfect in all areas of pitch – quick and easy. Bass drums have an extremely wide range of depth. The set I play was made for me to celebrate Ludwig’s 100th Anniversary.”

“Perspex is not as loud as stainless steel but has some similarities in the projection and tuning. The Blue Ludwig Vistalite set that I have in Europe has always sounded good straight out of the cases and the new welds used in the shell construction make tuning a lot better and quicker. The drums retain their sound overall throughout a concert. They are not as loud as some wood drums, but are very clean-sounding. And the heavier the head, say an Emperor or CS Black Dot, the better the sound overall. Because the low-end on these drums takes some time to get on the smaller sizes it is down to tuning the drum how you like it and hitting it harder for projection. The drums sound inspirational when you are behind them, but from out front it is a lighter sound overall. But these drums have a certain magic when you record them. The floor toms can sound fantastic.”