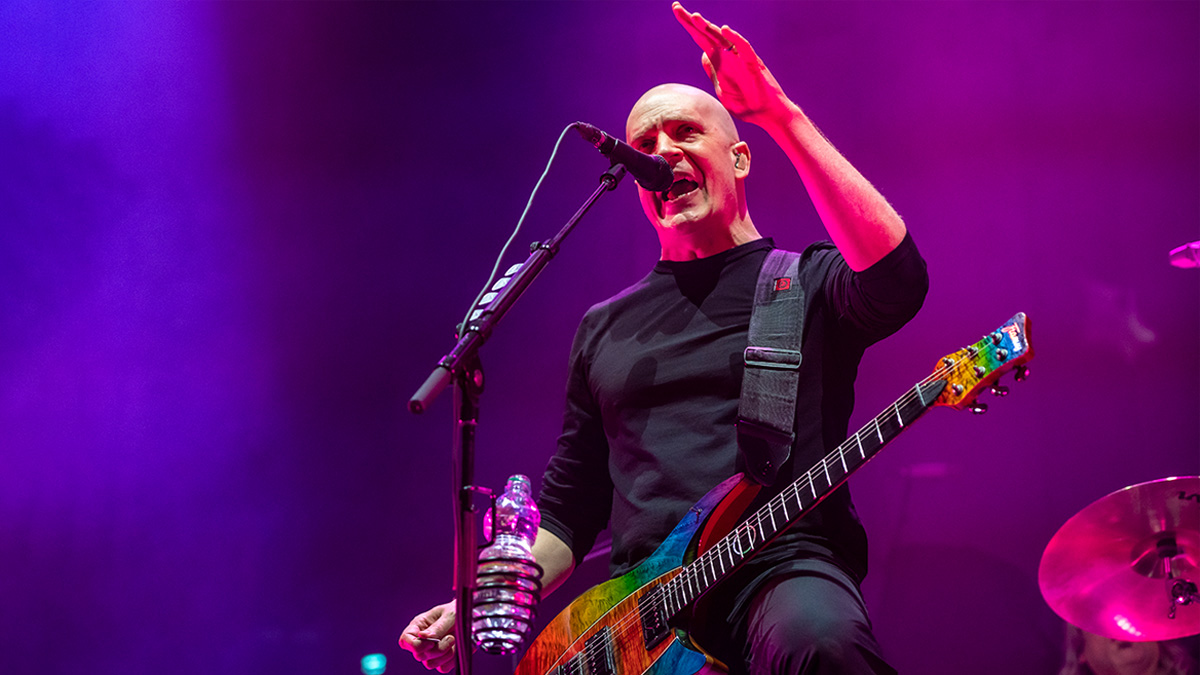

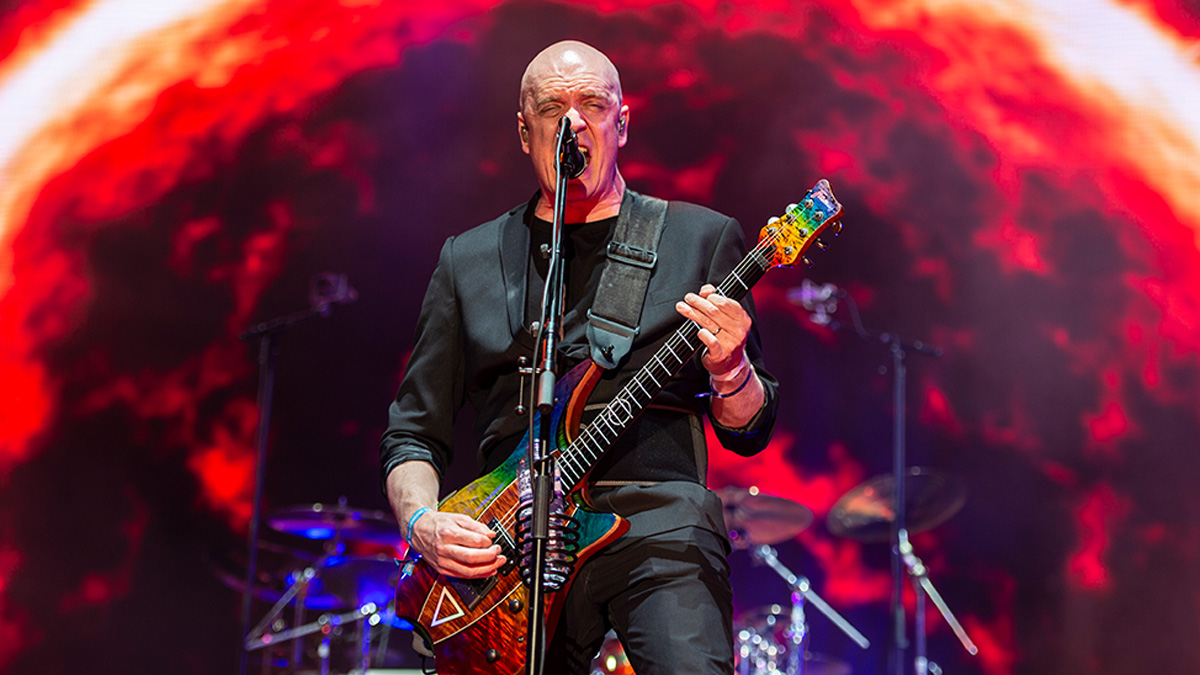

Devin Townsend talks Infinity and beyond: "It was a lot of folk music… a lot of abstract orchestral music – because of Star Wars, because of The Dark Crystal... and then Def Leppard, Metallica and Enya and we’re good to go"

Townsend reflects on his Infinity album anniversary, genre-bending, and why he remains inspired by delay and listening for patterns in abstract loops

Devin Townsend might be gone some time. Sure he’ll break cover now and again for his podcast – just this week he was in conversation with Tosin Abasi. But if anyone needs him over the next however months they’ll find him in his “cocoon”, writing whatever The Moth is going to be.

What that is right now, how The Moth might sound, he can’t say just yet. The prog-metal trailblazer is grasping around in the dark, looking for electric guitar tones that might give shape to its sound.

“It’s like a needle in a haystack, the beginning of any process,” he says. “That’s where I’m at right now with The Moth. I’m going down avenue after avenue and trying things, and experimenting with things, and people are sending things and I’m trying that, and I’ll go a certain direction and think that I’m onto something and then realise it’s not, then I’ll go back and go in another direction.”

Even if Townsend has more gear options than ever before it doesn’t make the search any easier. Digital tech has brought us more tones than ever was possible but when you are trying to articulate a feeling in a guitar sound there is always going to be some degree of latency between brain and machine.

Luckily, Townsend isn’t here to speak to us about The Moth. He’s here because Infinity, his third studio album as a solo artist, celebrates its 25th Anniversary, and has been remastered and reissued. It’s was a big deal then and is a big deal now. How else could anyone persuade Townsend to be photographed once more in the altogether for the album cover?

“The mental preparation that went into doing a photoshoot like that when I am 51 versus 25 was more than twice as difficult, I’ll tell you that,” he says with a chuckle.

Infinity was a big record. It captured Townsend’s sound at an evolutionary turning point. The ideas he was driving at on Ocean Machine were developing apace; the synthesis of reverb and delay, of the muscular metal riff and the ethereal wash of his melodic sensibility and spatial awareness.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

It was an album that holds the physical power of metal and theatre in equilibrium, and 25 years on it still sounds of the future, a work of sonic frontiersmanship.

Loops. That’s where I’m at at this moment. Loops, but not in the sense of house music or anything but I like repeating abstract patterns that morph over time

Townsend’s aesthetic over the years has careened from pole to pole, from the industrial maximalist metal of Strapping Young Lad to the hypnotic ambience of The Hummer, to the sci-fi comic musical theatre of Ziltoid.

The through-line is his intent; the search for awareness, of who he is and what he wants to say in his music. And as he explains here, it all began with musical theatre and the dramatic geography of British Columbia, nature presenting its own form of Infinity for a young Townsend’s mind to roam.

It’s nuts to think that Infinity is 25 years old because it still sounds so fresh. You still have the likes of Bad Devil and Truth in the setlist. How do you feel about these songs now? Do they feel different to you. Do still feel connected to them?

“I feel both of course – probably because I am different. But upon trying to interpret music from the past in different ways I have come to the conclusion that it was written to be precisely what it was, and I draw the conclusion from that that I did the best that I could at the time.

“In the same way that I feel about the music that I’m currently making, I reflect on that stuff from the perspective of, ‘Oh yeah, that was me too!’ I couldn’t have done that any better with my toolkit at the time. Playing that stuff now is akin to making peace with yourself on some level.

“Part of that, for me, means trying to be true to how it was meant to be, right? How it was meant to go. How does this song go? What does it mean emotionally? Where does this take me? And then it is relatively easy to reconnect with that just if you get the parts right.”

At the time, you had this sort of Ren and Stimpy anarchist persona. You were a bomb thrower. But if there’s a through-line from then to now, there’s maybe that sense of Broadway, of show tunes. Like this is progressive metal, but make it a show.

“[Laughs] Maybe! I think you are just a product of your influences. More than musicals and show tunes became like a draw for me – like, ‘I am a show tunes guy!’ – it’s just that my formative years were comprised of all of that stuff, so you just end up internalising it.

I was indoctrinated into the world of musical theatre from such a young age

“From my first moments on Earth to about 10 or 12 years old, it was during the ‘70s, right, and those types of media were everywhere, and my parents loved them, so I was indoctrinated into the world of musical theatre from such a young age.

“As someone who is in his 50s now, I listen back to them and, other than nostalgically, they don’t really resonate with me in the same way. But I think why they did at the time is that they are such overt displays of whatever emotion they were trying to put across.

“They were a broad stroke from a huge paintbrush, so it was not like a nuanced example of love or hate or any of these emotions; there were just people dancing on car roofs. ‘This is what hate sounds like! This is what sadness sounds like! This is what love sounds like! And looks like!’ And because it was such a part of my formative years, I just internalised that and the became part of my repertoire.”

And you take that grammar of show tunes of musical composition into your sound. Wild Colonial Boy always had this sort of Danny Elfman quality to it, and the way that the vocal and the guitar are almost in a dance with each other.

“It’s a lot of Clancy Brothers, too, to be fair. [Laughs] Like, the Wild Colonial Boy, just in general, my grandfather was from Ireland and came to Canada when he was an adolescent. We were just so inundated with Irish folk, and Wild Colonial Boy was just a direct throwback to that on a lyrical level – and then maybe on an aesthetic level there was a lot of Mary Poppins in that one!

“Because that was also a film. ‘Feed the birds…’ That whole thing, with the most atrocious British accent of all time by Dick Van Dyke, but it was such a huge thing. I watched that film endlessly. Not of my own accord, necessarily but it was just such a big part of my life in my family, and so I think that, no matter who you are, you are going to subconsciously absorb [it]. And like you say, it becomes part of your aesthetic, and that was it for me.

“It was a lot of folk music, a lot of musical theatre, and then a lot of abstract orchestral music – because of Star Wars, because of The Dark Crystal. In that period, all the sci-fi films I liked were just festooned with Romantic, classical motifs, and a lot of it was drawn from the Stravinsky stuff.

“It was easy to identify through that as well. ‘Oh that modality, that is what the bad guys sound like.’ Right? ‘This type of modality, oh that’s a sweeping sadness, when his parents are dead.’ Or whatever it is. You just internalise it. And then Def Leppard, Metallica and Enya and we’re good to go.”

Ginger from the Wildhearts is credited on the record but what was his contribution?

“I was in the Wildhearts for a year. I lived in the Midlands and did the whole Midlands trip of crushing depression in the ‘90s. [Laughs] But Ginger was involved to the extent that he was in my life, and he was a big personality, and so just by the nature of my trajectory and where I was in terms of personal growth at that point, I was in a band with him.

“I was spending a lot of time with him. He came and stayed with me and my wife in Vancouver for a long time, a significant amount of time at least, and it was a difficult relationship at the time because we were both in crazy places.

“He is involved more so from an influence point of view rather than like a song-wise, structural point of view. I think that he contributed a chord every now and then but it was more of his presence that was an influence at that time.”

From the outside, Infinity just seems like such a heavy lift – metal but make it Nasa – and you inaugurated that sound on this record. It’s your sound walking out of the primordial goo and taking form.

“No, you’re right, 100 per cent, and it’s funny, all the work I’ve done has gone through so many aesthetic shifts – arguably every record is a different aesthetic. The differences between Deconstruction and Ghost, Alien and Synchestra, any of them. There are so many different aesthetics – Casualties Of Cool or Empath or any of those things, Ziltoid… There has been a constant within those aesthetic shifts that has been pointing towards something.

“What I would postulate that trajectory is is just refining that awareness of who you actually are, and that has been consistent through all the records, and, as you say, Infinity is a primordial starting point. Although, Ocean Machine was arguably more defined in what it was meant to be.

“Ocean Machine signified the end of an era of writing. I started writing Ocean Machine when I was 16, 17 years old, and that carried on through the Steve Vai experience and the Wildhearts experience, and so when that record came out it had a more solid identity because I knew what all that stuff was. I had had those experiences as a teen and I was able to say that was how I am – the death of my friend, and all of these sorts of things.

“Infinity was like the birth of a new thing for me. I had gone through the machine of Steve Vai and Wildhearts and started experimenting with drugs and drinking and sex, and all of these sorts of things that I had just had no experience with. I was so naïve in so many ways.

“When Infinity came out, there was a momentum behind it, just the intensity of the newness. But it certainly was just an explosion in every conceivable direction. I do feel like, since that time, I have been refining it in that direction.”

Every direction. Some of the sounds you were coming out with then are totally nuts, the guitar sounding almost confected. And by the middle section of Noisy Pink Bubbles, the sound owes more to Plastikman and acid techno as it does metal.

“One of the things when I first started my career, people found very confusing, and I was always confused by their confusion, is that I would do all these different things because I would listen to so many different things.

“In the ‘90s, man, I listened to so much techno. I listened to so much house music. We were listening to The Orb. My buddies were all 808s and 909s, a lot of space and reverb, and the intentional vocal samples, and all these kinds of things, and to me, just because I am a fan of music, it seemed like of course you would listen to that because it’s cool.”

“It’s not like if you are in a certain genre you should limit yourself to that, otherwise you’re stepping outside. It’s like there’s no nuance between opinions lately, is what it seems. It’s not like you can say, ‘I do believe that but I also believe that. I agree with you. I also agree with them, and somewhere between that it’s a grey area. It’s not so black and white.’ Listening habits for me were never black and white. I loved everything – except for the stuff that I didn’t love and I absolutely hated! [Laughs]

In the ‘90s, man, I listened to so much techno. I listened to so much house music. We were listening The Orb. My buddies were all 808s and 909s, a lot of space and reverb... of course you would listen to that because it’s cool

“I think when I first came out people were like, ‘I don’t understand.’ It seems indicative of some kind of schizophrenic personality disorder that you would release something like Oh My Fucking God and then also do things like Thing Beyond Things, or do Death Of Music, or Punky Brewster, and I was always confused by that because I thought, ‘No. I like all of those different things.’

“It is a simple thing. I am a musician – not a genre-dependent musician. It’s just I love all sorts of music. In the same way that my aesthetic was informed by musical theatre it is exactly the same with those listening habits I had in my 20s, right?”

Those habits have a certain consequence then because then you have make something of them, and you almost had to reinvent metal guitar tone to make it sit with synthesizers. How did you figure out what you wanted from your guitar sound?

“Well, as you suggested earlier, Infinity was a primordial starting point for that. I love that word in regards to it. Yes, to answer the question. You have to figure it out, and in a lot of times the guitar sound informs the direction of the music, and so frustrating as it is – and it is – a big part of the process of almost every record is finding a guitar sound that seems to fit with what I am feeling. And because, regrettably, I can’t visualise the aesthetic of the end result, I can only visualise what I want it to make me feel. If that makes any sense.”

The digital age has been good to you in that regard. You’ve got that reference-quality appreciation of space and sheen, and how you want the reverb and delay to sit with the muscle and physicality of metal guitar. It used to be you found the rhythm guitar tone and it pretty much set how the record would sound. You need a broader palette.

“Yes but I can simplify it and take a lot of the romance out of it. When I was learning how to play, so much of what I wrote, I tried to replicate the vibe of certain types of nature. We lived in British Columbia, Canada, and we are surrounded by mountains. It rained a lot. A lot of miserable weather.

“And the grandeur of the mountains, and the mist, and all this stuff, I was always so inspired by just how that felt when we were driving through the mountains. We would go on vacation there when we were kids, and just drive through the mountains to get to Alberta or wherever, so I was always trying to replicate that.

“Because I wasn’t in a band, I fell in love with the idea of delay and how it worked when it came to things like Ocean Machine or Infinity. To this day, if I wasn’t playing with anyone else, if it was just me on my own with a lot of delay, the tails of the delay interact with the next chords that you are writing in specific ways.

I would often use delay and reverb as a way to inform the chords that come after each other so that when it is played in a bigger place it has this monumental feeling

“If you’ve got a lot of delay and you go from an E power chord to a Bb power chord the echoes are going to do this crazy, dissonant thing that creates this cloud of grey nothing. However, if you are playing a C suspended and then go to an Asus2, that sort of interval, the delays do this with each other and they become congruent.

“The reason why that implies a sense of grandeur to me is that you can play it in bigger places and it still works. It’s like it harmonises with itself, so I would often use delay and reverb as a way to inform the chords that come after each other so that when it is played in a bigger place it has this monumental feeling to me as opposed to dissonance.”

At the risk of sounding too romantic there is something spiritual about that delay, like you are shedding a musical skin, the idea is shedding its skin and it is all held there in suspension, in a sort of atmosphere.

“Totally. Spiritual is such a loaded word, because everybody is so angry about everything. I wish there was a different word for it but that is the foundation of everything that I do, man. Even the stuff that was super toxic, because there was no intent on my side to make something that was, like, bad for people!

Even through Alien – things like Shitstorm and Info Dump – and all these incredibly jarring things that I’ve also written, the process has been to try and reveal yourself to yourself

“Even through Alien – things like Shitstorm and Info Dump – and all these incredibly jarring things that I’ve also written, the process has been to try and reveal yourself to yourself. That sounds a little suspicious! [Laughs]

“The one constant throughout this journey for me is nature. That’s just the source of it. And the universe, the sky and the mountains, and the water, and rain… You know what I mean? That’s where the inspiration drew from, so why I say that spirituality is kind of a dirty word is because it is so heavily equated to a lot of these dogmatic organisations that seem to be at the root of so many of society’s ills.

“But I’ll also be quick to say – I don’t fucking know, man! I’m not enlightened. I’m not smart enough to understand this stuff. All I know is that, as an artistic soul, those things, I’m a part of them... I find it very inspiring and I want to write about it.”

That comes down to what you were talking about in your podcast, that it comes back to intent. This is an under appreciated word because the intent is fundamental to what you are going to do. Do you know what the intent is for The Moth?

The most important thing I have learned from all of this is it is never going to be perfect and that is the whole glory of it! If I ever got it right I would never do it again

“No. That’s the process. Somebody in the last interview I did asked, ‘Was Infinity the most important record I done?’ And my answer to that, and without a shred of false modesty, is that none of them are important.

“Like, none of the records are important; it is why you did them [that is]. I guess the easiest way for me to describe it is the records are a document of the journey, and the intent – to the extent that you are able to articulate it to yourself – is the most important thing.

“The most important thing I have learned from all of this is it is never going to be perfect and that is the whole glory of it! Y’know!? [Laughs] If I ever got it right I would never do it again. There is something about being an imperfect perfectionist that is fucking hilarious.”

Are there sounds that excite you? There are so many sounds that are available to us that it can be inspiring or paralysing but what excites you at the moment?

“Loops. That’s where I’m at at this moment. Loops, but not in the sense of house music or anything but I like repeating abstract patterns that morph over time – and this is just where I’m at currently – that have very non-linear musical harmonic content that then, by the sheer fact that it loops, you can extrapolate from that certain hidden melodic motifs.

“Even on Ocean Machine, Voices In The Fan, ‘cos when I was a kid I would listen to repeating patterns and things started to appear because the human brain is such a pattern-seaking [organ]. We don’t want to get eaten by a lion so we are looking for patterns as self-defence, I guess, and so when I listen to loops I really enjoy that repetition and how that starts to imply emotional things to me.

In the past I have always worked with that to some degree but I think, at the formative stages of The Moth, whatever it ends up being, that’s where I am at. At least right now it is abstract loops. But because I have done The Puzzle and it was so abstract that it lost a lot of people, including myself to a degree, I am able to say, ‘It’s not far but it’s there,’ and you just follow your compulsion, right?”

- Infinity 25th Anniversary reissue is out now via Inside Out.

Jonathan Horsley has been writing about guitars and guitar culture since 2005, playing them since 1990, and regularly contributes to MusicRadar, Total Guitar and Guitar World. He uses Jazz III nylon picks, 10s during the week, 9s at the weekend, and shamefully still struggles with rhythm figure one of Van Halen’s Panama.

"No one phoned me. They never contacted me and I thought, 'Well, I'm not going to bother contacting them either'": Ex-Judas Priest drummer Les Binks has died aged 73

“I called out to Mutt and said, ‘How about this?’... It was a complete fluke": How Def Leppard created a rock anthem - with a little bit of divine intervention