Derek Trucks: “I love hearing the Strat with the slide. Clapton is more tucked in. Duane’s slide sounded like it could totally flame out or go off the rails at any time“

Trucks takes a deep dive into the Derek and the Dominos classic and explains how Tedeschi Trucks Band captured its forbidden passions and guitar genius live for Layla Revisited

Tedeschi Trucks Band's Layla Revisited (Live at LOCKN') is what we could call an event record. It captures the band performing Derek and the Dominos' Layla And Other Assorted Love Songs in its entirety on a heady August night in Arrington, Virginia.

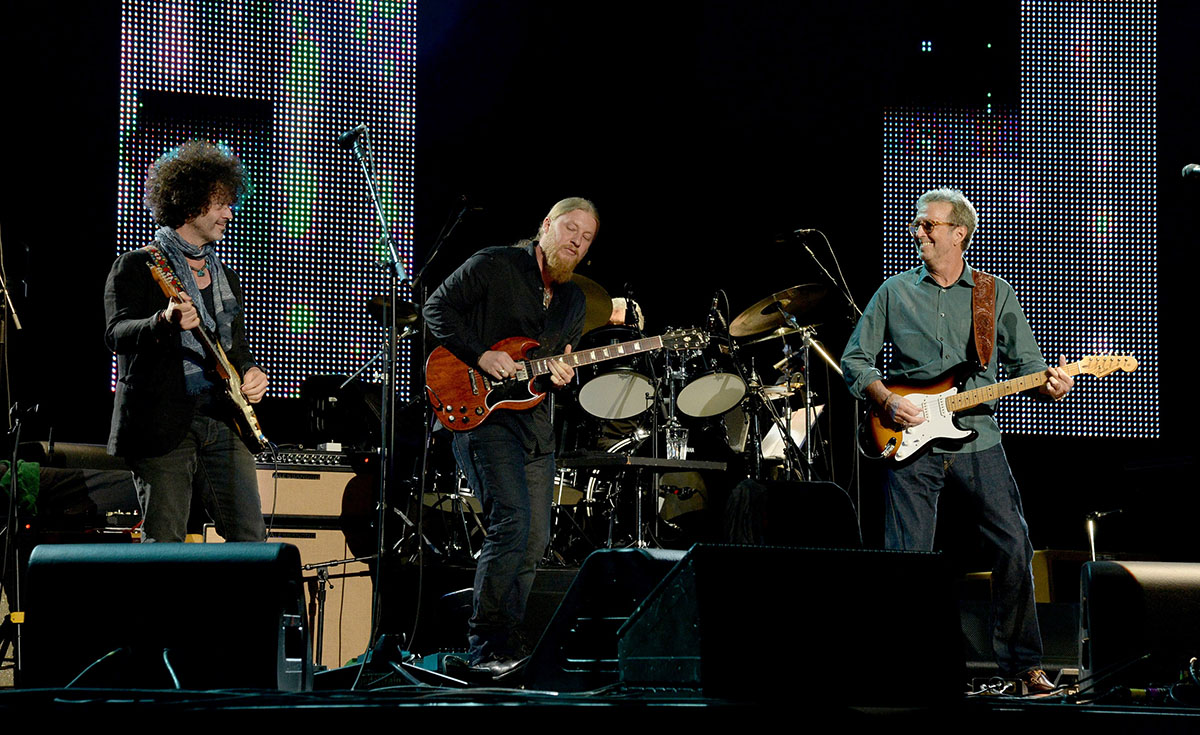

It was a night Doyle Bramhall II and Trey Anastasio joined them on guitar, but maybe also the spirit of Duane Allman and others, too, because, as guitarist Derek Trucks explains, this night was special. How could it fail to be?

Besides the cosmic significance of singer/guitarist Susan Tedeschi being born on the same day as the album Layla..., was released, and Trucks being named after the band, there are all kinds of connections to the material and the Tedeschi Trucks Band's lineage. And there was plenty left for them to explore.

Layla... is that sort of album. It was Eric Clapton's epic cri de cœur, inspired by the Layla and Majnun poem and given its emotional trajectory from Clapton's hopeless attraction to Pattie Boyd – his best friend George Harrison's wife. It is a classic of blues-rock. With Clapton trading licks with Allman, it became a high-water mark for the electric guitar, and yet it seems a little reductive to look at it through the lens of the guitar. It's so much more.

I think it will resonate with people. It feels good getting it out right now, especially as we are getting back to touring and playing again. The timing feels good

The material draws on the history of blues to fathom the depths of heartbreak and unrequited love. It references the canon, the rock 'n roll songbook, and gives it its own energy. As Trucks explains here, that's the job of the artist, to build on what's gone before, to borrow wisely and steal if you must, and if you do so and get it right, you extend the lifespan of these ideas and keep the sound alive.

Ironically, the eventless horizon of the past 15 months gave Tedeschi Trucks Band the opportunity to revisit their performance, dig the tapes out and get mixing. At first, just to test the water. But in a year without shows, those memories were overwhelming.

“It reminded us of how good that whole weekend and that show felt,“ says Trucks. “It reminded us what it felt like to be in front of an audience when something was happening. [Laughs] When we were mixing this record, it just hit us: ‘I think this is good enough to release.’ I think it will resonate with people. It feels good getting it out right now, especially as we are getting back to touring and playing again. The timing feels good.”

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Tedeschi Trucks Band has performed some of the Layla... material before LOCKN' 2019. Both Trucks and Bramhall II have collaborated with Clapton. But, as Trucks explains, to pull the show off, everyone had to go deeper into the record...

Layla And Other Assorted Love Songs is many things. It's a triumph of writing, performance and production, but given the subject matter, it is also almost difficult to listen to. It sounds so intimate. How important was getting that tone right for this performance?

“When you approach a record like this you definitely have to be holistic about it. You have to think about [everything]. I mean, for us, there are loose family connections to the record, and there is the connection with Eric, and the connection with me and Sue just being a married couple.

“There are a lot of themes on the record where – like you said – at times it is difficult to think about or hear those things. Or to sing about them or play them! [Laughs] Y’know, we are a 12-piece band and everybody is of an age where everyone has been through the fire a few times in their lives! But those things hit home for a reason, and certainly, when you are tackling a piece of work like this, you go to those places when you are really digging in.

“There are moments when we were playing this material live and you could feel that. You could feel from the singers or the players people really tapping into that energy, and that place where the album came from. If they are not universal themes, then they are really close to universal themes. Everyone has been in that spot once or twice, or currently or whatever. [Laughs] You’re definitely playing with fire.”

And if you haven’t already, you surely will. No one gets out alive.

“Exactly. You won’t get out unscathed. That’s for sure. [Laughs]”

Both TTB and Derek and the Dominoes are at your best when jamming it out. Did you start with the jam songs first or did you go chronologically?

“There were a handful, maybe three or four tunes, that we had performed and had in our repertoire before we took this on, so when we jumped in to this, we really started from the top. We had a few weeks, a few months of working on it with our band, and then we finally had a rehearsal with Trey, and one with Doyle in the days leading into it. But I think everyone jumped at different tunes at different times.

There is some beautiful stuff on there, and really difficult things on there. Just hearing Eric mess with different tunings and the different approaches.

“The ones that I hadn’t played – I Looked Away, and some of the earlier tunes on the record – it was really nice to jump into them because I had never taken the microscope out and really listened to all the parts, and it made me appreciate the record that much more. There is some beautiful stuff on there, and really difficult things on there. Just hearing Eric mess with different tunings and the different approaches.

“Sometimes you can tell he’s thinking as a singer-songwriter, and other times you can definitely tell it is coming from the instrument out. It is fun to dig into a record that way. One way is to sit back and enjoy it, and that is how I have always approached it before this, but I’d never really dug in and picked it apart – without getting too analytical on it. You want to keep the spirit of the thing. That’s first and foremost.”

Sure, you don’t want to lose that energy by over-intellectualising it. These guys were making it up as they were going along anyway, and they even kept the errors in, like that vocal cue.

“Yeah, totally! [Laughs] That’s right, and sometimes the mistakes become part of the canon.”

The imperfections on a record can be everything. Perfect is boring.

“That’s the honesty of the thing, what you really connect with on an emotional level. One of our mutual heroes and gurus, Col. Bruce Hampton, he would talk about that all the time. He would say, ‘I don’t want to hear anyone who sounds the same everyday. You should sound different if you hit the lottery or if your grandmother died. You should feel totally different.’ But for some people, it just doesn’t matter; it’s all brain and no heart.

“Our favourite records and our favourite recordings are just riddled with problems! [Laughs] That’s kinda the beauty in it. It makes you realise that your heroes are human and there are flaws all over it. But it also makes you realise that they are all superheroes, because they took this amazing personal thing and made it timeless. It makes you feel things you didn’t know you had, and that’s quite a gift.”

This is a very interesting record, but especially for you, being such a great slide player, and tackling a song such as Anyday, where Clapton plays slide. How do the styles differ between Duane and Eric?

“There are the obvious tone and sound differences just from what you are hearing from different instruments, but Eric definitely has a unique approach. I always loved him playing slide. He didn’t do it a whole lot, but on Motherless Children, or Anyday, there’s just a great feel to it. And it reminds me that, early on, before I knew what was what, I just assumed that was Duane when I was younger.

I love hearing the Strat with the slide. I just love hearing that approach. It’s a little more tucked in whereas Duane’s just sounded like it could totally flame out or go off the rails at any time

“There was a track on Eat A Peach – I think it is Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More – where I assumed it was Duane but it was recorded right after he passed so it was Dickey Betts who was playing slide. In my head, I always equate the way Dickey and Eric played slide because they are obviously straight players first and slide is this thing they came to later. Duane was, too, but it became very much part of his sound that he almost eclipsed his other playing.

“I love hearing the Strat with the slide. I just love hearing that approach. It’s a little more tucked in whereas Duane’s just sounded like it could totally flame out or go off the rails at any time. It was so wide open with the way he played, whereas Eric was very precise, which is cool to hear. But I love the sound of his slide playing.”

You’re right, and they do work so well together, with Duane having that sort of Two-Lane Blacktop vibe as though the hotrod is coming off the road…

“Yeah, totally! And I think Eric’s slide playing is probably heavily influenced by George Harrison, too. You can hear those inflections in his playing.”

Not all Eric’s obsessions about things that were George Harrison’s were unhealthy. Thou shalt covet thy neighbour’s slide technique!

“[Laughs] That one’s okay. That’s true! It gave us some good things.”

Little Wing must have been tough. You’re not just covering Hendrix, you’re covering Hendrix by way of Clapton, Allman et al… Does that give you a little bit more freedom just to cut loose?

“Yeah, the beauty of that is we have heard so many people cover Little Wing Hendrix-style that I probably wouldn’t be comfortable doing it. It has been done so many times in so many ways. But the Dominos version, it’s just kinda there, and no one ever talks about it.

“I don’t think I have ever heard anyone cover that version; it was fun to be able to do that, and yeah, it does give you a little bit more freedom because that path is not as heavily walked. You feel good about it. We did it a few times on the Clapton tour. Not a whole lot but I think I played that a handful of times.”

And you’ve got to be careful because Little Wing can be a little 3pm at the guitar store…

“Totally! That’s funny, because we have a running joke at soundcheck or in the studio, if somebody shouts ‘Guitar Center’ everybody just starts playing whatever and it sounds like a cacophony! [Laughs] But yeah, some covers of it can sound a little bit guitar shop.”

We are very much looking forward to the Tedeschi Trucks Band’s cover of Enter Sandman…

“It’s comin’! [Laughs]”

We have a running joke at soundcheck or in the studio, if somebody shouts ‘Guitar Center’ everybody just starts playing whatever and it sounds like a cacophony!

Did you play the Goldtop on it?

“I did. I played the Goldtop that I have, and it’s one serial number that’s off the Duane Goldtop. That’s one a few tunes, Little Wing being one of them. And then I played the SG that I always play. It was just those two instruments.”

Did you get to play the original Duane Goldtop?

“Yeah, quite a few times. That's why when this Goldtop ended up at the big house, at the Allman Brothers House in Macon, Georgia, Richard [Brent], the curator, called me about it and said, ‘I think you are going to want to play this guitar.’ It was going to be much more within my reach for purchasing than the Duane guitar! But it is an incredible instrument, and it really is similar to Duane's.

“The neck dimensions are unique for that era. Usually, the ‘58s have massive necks and these things are a little bit more trimmed down and maybe a different shape. You can tell they were probably finished by that same person, that same day, and it’s just an amazing instrument. I am really lucky to have found it.”

What about Nobody Knows You When You Are Down And Out, the Bessie Smith/Jimmy Cox standard? Can you talk a little bit about playing that track, but also about playing blues standards, because you have Keys To The Highway, too, which is the quintessential blues standard, complete with a contested origin…

“A song like that is just part of the songbook. It has been done a thousand ways. Two nights ago on the bus, we were just watching A Well Spent Life, the Mance Lipscomb documentary, and he is playing a tune that is just 100 per cent Key To The Highway progression but he was born in 1895 so I am going to believe him, too! [Laughs]

“These are song-forms that have been passed down and they take on all kinds of life before there was recorded music, and that is one of the songs that goes all the way back to the beginning. Key To The Highway is interesting because, by the time that we had done this, I had played Key To The Highway with Eric, I had played it with BB King, we had done it with the Allman Brothers, and there were a lot of faces and feelings that come up when you play a tune like that.

Nobody Knows You When You Are Down And Out is one we played every night on the Clapton tour during his acoustic set, so whenever that song would come up it would immediately bring me back to that place

“When we started playing it, I am thinking Duane and his sound, I am thinking about Greg, the last time I saw BB sing, ‘When I leave this town/I won’t come back no more’ and thinking I believe him. I think he is actually telling us that. There are a lot of different feelings that came up when we were doing Key To The Highway, because it is on the Dominos record but it just part of the history by that point.

“Nobody Knows You… is one we played every night on the Clapton tour during his acoustic set, so whenever that song would come up it would immediately bring me back to that place. Different feelings you get for different reasons. But when you are doing material like this, all of it relates back to that circle.

“I would think about Gregg, I would think about my uncle [Butch Trucks, founder of The Allman Brothers Band]. You would think about the guys you didn’t know, like Duane. You think about Eric and BB, and people who felt really close to you, so that’s an interesting thing when you are playing music when it is tied to your history and a broader history.”

Perhaps that is one of the reasons why the blues is so eternal, because you can take those standards and adapt them to your own story. In turn, maybe because blues such an elemental part of rock ’n’ roll, that’s why rock is similarly eternal, self-renewing.

“I agree with that. There is something to the fact that – and you’re talking about Key To The Highway and its contested origins – that’s the same with all of this music. Me and Susan were out there in Los Angeles for this Grammy Award where they were inducting Bob Dylan and he gave this incredible 45-minute speak – it was pretty combative towards the music industry. But he said some really incredible stuff of his early days and playing folk music, and he was like, ‘If you had played Key To The Highway as many times as I did, you would probably have written Highway 61 yourself!’ [Laughs]

“And it made me think: we are all borrowing. It’s all part of this turnover of the soil, and it is all the things that are in there, and it is your collected history, it’s the scene’s collected history. It is the collective musical consciousness that you are reinventing, and any artist that feels like they are reinventing the wheel, I always question it. Any time you get too hip for your own good, I wonder where the roots are.

When you played with BB or hung out with BB, he would talk about passing the torch. You could tell it made him feel good when he heard somebody from another generation tap into that spirit

”Some people do come out of left field but then you realise they really didn’t – even a character like Hendrix, where it seemed like he was dropped from another planet. 'Oh no, that’s Little Richard, or that’s Albert King', and he didn’t hide it; all his roots are there. Sun Ra happened, too! [Laughs]

”We’re all borrowing and we are all part of the continuation of the story. The greats that we have been lucky enough to be around, they were fully aware of that, and wanted that to keep going. When you played with BB or hung out with BB, he would talk about passing the torch. He would talk about it. You could tell it made him feel good when he heard somebody from another generation tap into that spirit.

”He appreciated it knowing that that little bit of the sound was going to keep going, or if he heard Sue sing something, he would light up, because [he knew] this isn’t going anywhere. No one is ever going to be him. Nobody is every going to be those characters – Duane, or any of them – ever again, but some of that fuel or that fire is still there. I think that is what you are talking about, too. It is self-renewing.”

Records aren’t sequenced like set lists. But this one feels a little bit like a set. The first two songs on the record are the first two songs that they wrote, and that seems to give it its own momentum

“A hundred per cent. It is really interesting record that way, where it ends. With the exception of Thorn Tree…, it ends with the obvious set closer, which usually doesn’t happen. And I am glad it does because it would have been really difficult to play Layla in the middle of the set and then follow it up with something else! [Laughs]

“Which is why, when we did the live concert, we didn’t play Thorn Tree… at the end. It didn’t feel quite right. And I quite liked the idea of putting on the original version kind of as walk-out music for the audience, so you can actually hear Eric and Duane and Bobby Whitlock. That was fun.”

We start getting the core of the band down to the studio and it led to an incredible amount of songwriting, and I think we have a few records in the can, of new stuff

That was a perfect end to the set. It was perfect, too, because it gave you and Susan a chance to play unaccompanied in the studio for the first time, for Thorn Tree In The Garden.

“Yeah! There were a few silver linings from the lockdown. Getting to do things like that that you just never get the chance… I mean, we tour and travel and play so much, you get home for a few days, it’s not like you go, ‘Let’s go record, just me and you!’ [Laughs] It was nice just having enough time, and this project itself came about because we had enough time to get out in the studio and pull out those tapes and go, ‘Let’s just mix this! This sounds great!’

“One thing leads to another, me and Sue record that track, and once we get the band tested, we start getting the core of the band down to the studio, and did a good six or seven good, week-long sessions there and it led to an incredible amount of songwriting, and I think we have a few records in the can, of new stuff, and it all came out of working on this project and having the time to do it. Which we have never had. We have always been road dogs.”

Sometimes the start of the creative process is just finding the space and the time to have a fresh perspective on your art.

“Yeah, totally, and reflection. We have been at it a long time, and there have been a lot of things happening over the last 10 or 15 years. The last two, three, five years, you try process while you are on the road, but sometimes being in the one place without all the external elements and excitement, just being home, really gave everybody the chance to take a deep breath and reassess things and get back to the point.

“I think there is going to be a lot of great music and hopefully we will move forward coming out of this. That is what you hope. I see evidence of both sides of that! [Laughs] Sometimes reflection or silence isn’t for all people! Some people don’t handle it so well. For us, there were some silver linings. But it was a hard time for everybody and we feel really fortunate to come out of it the way we did.”

You’re in love with your best friend’s wife, somebody you can’t have! There are songs in every culture about that

Have You Ever Loved A Woman is another devastating track. How did you approach that?

“I think that song, that reflects the feeling of the record as raw and brutally honest as anything else on there. And it is the most direct way to put it! You’re in love with your best friend’s wife, somebody you can’t have! There are songs in every culture about that.

“There are blues songs. There is Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan qawwali songs – Bewafa is just about being in love with somebody you can’t have. It is just a theme that is raw and hurts, and that is the easiest feeling to tap into because I think everybody has been on one side or the other or both.

“In some ways, especially when you are not just playing that song in a vacuum but in the middle of a record like this, you think about the lyric more than you ordinarily would, and you can definitely feel that with Trey and Sue, and the energy onstage. It was palpable that night.

“I don’t even know where everybody’s head was 100 per cent but it felt like we were digging into the heart of it. And I like the idea of Sue singing lyrics that were maybe gender-specific but you can sing it from the other side and it has an equally powerful meaning. I enjoy that.”

It makes perfect sense, and it gives it a different energy.

“Totally, and the whole Layla And Majnun poem, the Clapton record is very much the perspective of the lovesick guy, but there were two people in that relationship. It’s an interesting thought, like, what did Layla think about all this shit!? [Laughs] What was her take on it? It’s nice having Susan up there; it puts that thought in your head. ‘Oh yeah, this isn’t just a guy alone feeling bad. There are a lot of sides to this story.”

We mixed it in sequence and circled back and remixed because much like the Alessandro amp the old Neve console that we mix on it also warms up as you get going!

Such affairs of the heart deliver both agonies and the ecstasies. Have You Ever Loved A Woman is pure agony, then Little Wing is like a breather, and then It’s Too Late gets back into the ecstasy of it all with a guitar tone that made me laugh, because it’s the sort of thing we mortals chase for years, with your Alessandro amp heating up nicely by that point

“That’s funny. It did! I remember halfway through that show, going, ‘Oh it’s sounding really good!’ [Laughs] And the band did, too. There was a point in that show where you could definitely hear the nerves had completely worn off. Everyone was onstage, and you were just in it, and it was happening, and you were thinking, ‘Oh, this is really good.’ You’d feel a lift after every song. Never overconfident, but you could feel the band’s energy just get stronger and stronger, and everyone settling down deeper into the material.

“That was fun listening back to that when we were mixing it. Every song, as we got further down the road mixing the album – and we mixed it in sequence and circled back and remixed because much like the Alessandro amp the old Neve console that we mix on it also warms up as you get going! [Laughs] Sometimes you get to the end of mixing a record and you listen back to the first mix and you are light years ahead of it.”

There’s something nice about how gear and humanity works in concert, as it heats up, you heat up and things start flowing. Because at the start of the show, you can never be 100 per cent sure your fingers are going to be there.

“That’s true. That’s totally true. Everyone’s muscles get right, and when the temperature gets right, everything gets a little bit softer, and yeah, that is a good feeling onstage.”

Now, we’ve sequenced this conversation perfectly, which brings us to Layla. It’s another track that’s part of the pop-cultural furniture and yet it’s fairly radical in its structure. It’s like the album in miniature, the cresting passions and the fall…

“Totally, and I guess the outro could be interpreted a lot of different ways. The first part of the song is so tortured and and in your face, and by the end, it’s a resolution, but you are not really sure what direction the stream is flowing! Either way, it is a pretty incredible end to the record, with Thorn Tree like this coda.

It is one of those great moments in music history, just the connection that Duane and Eric had, and even just the difficult history of [drummer] Jim Gordon, and his tortured life, and the fact that Rita Coolidge probably had a big hand in it, too. There is a lot of history tied to that music, and it is complicated; it’s awful and it’s beautiful, and it is an awesome piece of work. The more you dig into it, the more there is to discover.”

- Layla Revisited (Live At LOCKN') is available to preorder, with all formats released on 16 July via Fantasy Records.

Jonathan Horsley has been writing about guitars and guitar culture since 2005, playing them since 1990, and regularly contributes to MusicRadar, Total Guitar and Guitar World. He uses Jazz III nylon picks, 10s during the week, 9s at the weekend, and shamefully still struggles with rhythm figure one of Van Halen’s Panama.