Del Palmer: “I was fortunate to have been involved in a lot of moments that have now gone down in history”

The former Kate Bush bassist on his remarkable career

Del Palmer first took up the bass guitar after borrowing the princely sum of £20 from his mother in 1967 to buy himself a Hofner Artist. One of the southeast Londoner’s very first bands, Tame, morphed into the KT Bush Band after Bush’s brother Paddy suggested that the group could offer his talented younger sister some vital live experience. On such fleeting moments does the course of history turn...

Palmer had already met Kate Bush back in 1976, when she was aged a mere 18. By 1977, the precocious, gifted teenager had decided to try her hand as a musician on the London pub circuit where, alongside Palmer, she performed early versions of the songs James And The Cold Gun and Them Heavy People. The pair soon developed a relationship as a couple, which lasted until the early 1990s.

EMI denied the KT Bush Band an opportunity to record on Bush’s debut LP The Kick Inside in 1978, but Palmer cemented his place as her main bassist later on her follow-up, Lionheart, and when performing with her on the Tour of Life in 1979. By 1985 he was working as a sound engineer on her sonic masterpiece Hounds Of Love, and continued in that role, alongside a gradually decreasing role on bass, until 50 Words For Snow (2011), Bush’s most recent studio album.

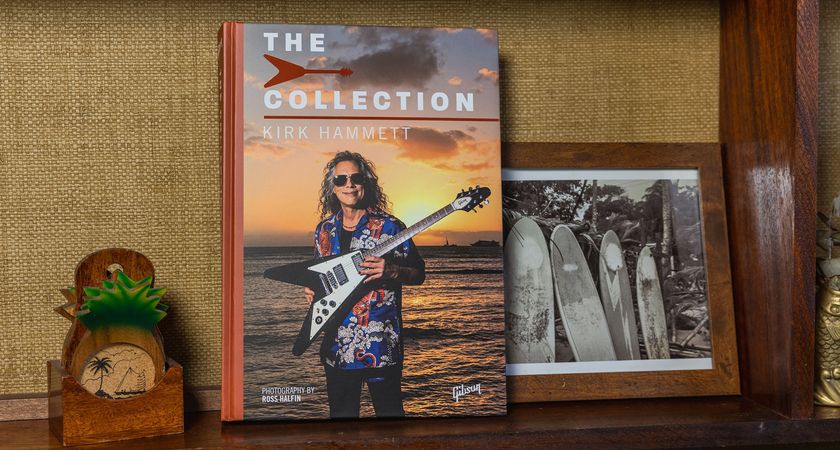

Last year, Palmer took to the stage for the first time in decades to perform many of the bass-lines from the Bush back catalogue with a cover band, Cloudbusting. With them, he paid tribute to The Kick Inside for the 40th anniversary of the album, and subsequently joined the group for an Irish tour. Aside from working with Bush, he’s engineered albums by Midge Ure and Roy Harper, and he released his third solo album, Point Of No Return, in 2015.

Cloudbusting band

There’s something about getting up on stage in front of people that is totally addictive

Why did you decide to tour Kate’s songbook with Cloudbusting, Del?

“It’s a very uncomplicated story. I was in Cornwall last summer on holiday, and Michael Mayall from the band lives down there. He said it would be nice to meet up so he could show me around some of the highlights of Cornwall, which we did, and we got talking about their 40th anniversary gig and playing The Kick Inside album. I thought this sounded really good and could be interesting. It soon got to the point where I asked to be involved. They didn’t ask me - I asked them! There’s something about getting up on stage in front of people that is totally addictive. I can’t understand why it’s taken me 40 years to do it again.”

Are they a tribute band, or a band in their own right?

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“I swore black was blue that I would never be involved with a tribute act, but after a while I realised that they’re not actually a tribute act. The music is more important than the sum of the parts, and the people involved are very respectful of this body of work. When the Kate Bush Songbook tour came about in Ireland, I jumped at the chance. I’ve always had a good time in Ireland and I’m a citizen there now. With what’s going on in Europe, it might be quite useful...”

How does your gear differ from the Tour of Life, 40 years ago?

“Back then things just weren’t invented! I had a small twin amp setup - one beside me and another behind the drummer so you could hear me. I would be standing right in front of the wedge monitors with no effects, just a volume pedal, because none of the music demanded it. I had a Precision bass with a Jazz neck on it. Someone said Ibanez were interested in fixing me up with some sponsorship, so I had two of them, one of which I used on the tour and another as a backup. I still have one of the two now. I use a fretless five-string and I also use an electric half- scale upright five with a high C.”

Do you use effects nowadays?

“The bass for Babooshka has a delay on it - it’s got a distinctive chorus delay, which is basically half the battle when you try and play that song. I use general output gain with no onstage amplification, as it all goes through the front-of-house PA. I have a personalised monitor where I can make my own mix: we use in-ear monitors. Back in ’79 those things weren’t even invented, so it’s a very different and much more complicated setup now.”

Early days

What was it like to return to bass parts such as Breathing?

“That’s such an inherent part of the song, and a beautiful line by my old mate John Giblin. I’m quite happy to defer to John, I could never take credit for it. It’s a credit to him how good it is. People still pull it out now and refer to it, and it’s humbling that people think it was me that played it, to be honest. The song is based around the bass: you’re playing figures and not just simplified lines, it becomes a duet with the voice. One moment the vocal is out front and next minute the bass has got the lead part. The MXR delay gives it that lovely, spacious sound.”

What were your early impressions of Kate back then?

She got this reputation as a recluse - whereas in reality she was one of the most outgoing people I ever met

“I thought ‘Where does this girl get all her energy from?’ She would be up at the crack of dawn, and she didn’t stop from that point onwards. She would travel into London for dance classes, come home and sing, then play and work on the music. When I was completely knackered and had to sleep, she would still be working on Wuthering Heights at two o’clock in the morning - to the point where we would get complaining letters from the neighbours. Up until 1979, she was absolutely full of energy and so driven to get her work out there.

“After the tour she wanted to redirect her energy into working in the studio. We did get some fantastic music out of that, but I really missed being out playing live and coming into contact with the fans in a big way. It was after that she got this reputation as a recluse - whereas in reality she was one of the most outgoing people I ever met.”

Do you have any memories of working onThe Dreaming?

“I remember recording the bass for There Goes A Tenner, trying to find the right kind of sound. It had to be very simplistic and not too involved - I had to make the song bounce, like someone running and making an escape.”

Which of your own bass parts have you been most satisfied with?

“I was very happy with Blowaway and also Night Of The Swallow, which was done very early in the morning. We used all three studios at Abbey Road to record that. We had the drums in one room and Kate was in the other. When we got that one down I felt elated, but I had to keep curbing myself because the danger was to throw in too much. I had to keep whittling down what I was playing to the bare bones, because it needed all that space in it to let the other instruments breathe. I’m very pleased with that, and Kashka From Baghdad on Lionheart. If you listen to that recording now, it’s clear that it should have been played on a fretless, but we didn’t know about them at the time because no- one was really playing them. I play it on one these days and it sounds very sexy and very moody.”

Doing the homework

Your bass would often take a lead role.

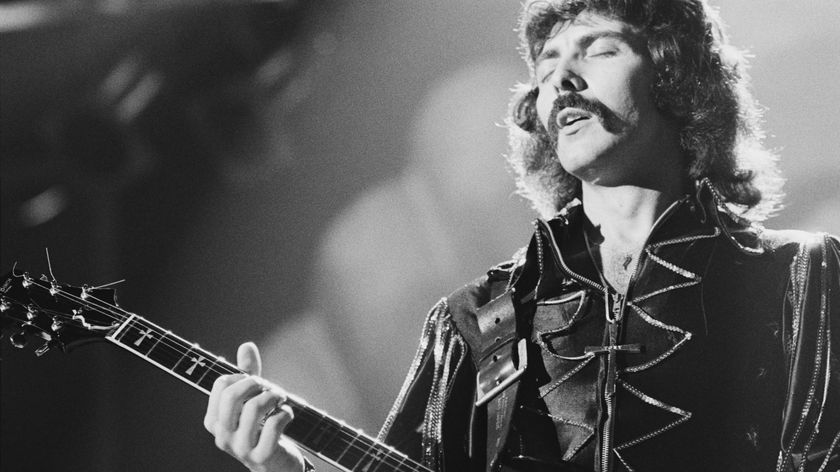

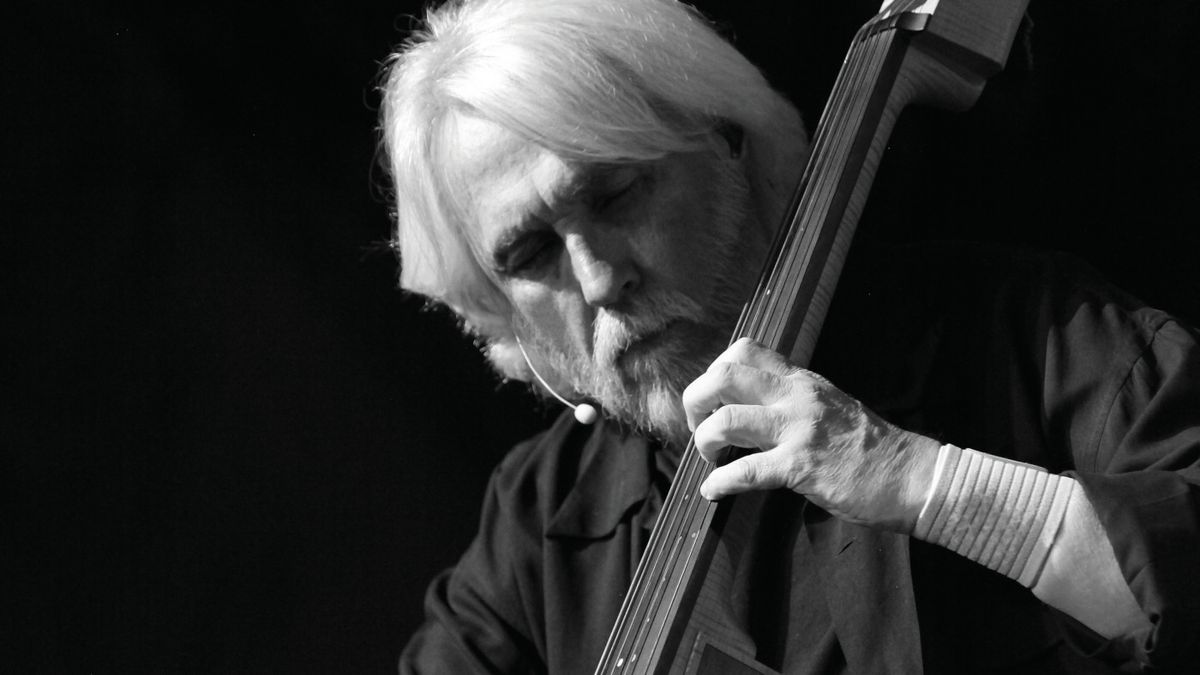

“Well, I admire [renowned jazz bassist] Eberhard Weber, who doesn’t just chug along underneath - he’s out there being the leader. It’s not that I want to do that, but I love the sound of a high-register figure with this very electric bass sound. It’s somewhere between an electric and upright bass. He’s such a beautiful player and has such wonderful interpretation.”

You recorded Hounds Of Love in Ireland. How much did the environment help with the album’s creation?

I’ve always been of the opinion that the best of Kate Bush is when she is sitting down at the piano and playing

“There’s a big Irish connection in Kate’s work. It probably started with Never For Ever (1980). When we did Hounds Of Love we stayed there for about a month, roughing it up and down the west coast of Ireland, and then we went to Dublin for two weeks. There was one spot in Ireland where we arranged to have a piano, so Kate could play and work on material. The second side was mostly written there and the rest of the songs were done in London.”

You must have had some fascinating creative experiences in the studio.

“I was fortunate to have been involved in a lot of moments that have now gone down in history. If you take This Woman’s Work as an example, it was created for a film project and done very quickly in an afternoon. You don’t realise that what you’ve just worked on is going to go down in legend. As far as you’re concerned, it’s just another recording session.”

What are your thoughts on Kate’s later work?

“I’ve always been of the opinion that the best of Kate Bush is when she is sitting down at the piano and playing: everything else is a distraction. Getting other musicians involved and looking for various sounds dilutes the purity of it all. The best stuff she’s ever done is piano and vocal songs. There’s always one on every album - one of those pure moments when it’s just her.”

You’ve continued to work with her, all these years after you first met.

“That’s right. On Aerial (2005) the most enjoyable thing was working with just her and the piano: we weren’t doing the long hours any more. Towards the end of the sessions we’d basically do office hours - we’d start about midday and work until seven and that would be it. By the time of the session she had the song, and had played it over and over - she knew it backwards. I set up the piano and vocal mic and she sat down and played it. That’s all there was. She’d already done the hard work in her own time, she’s done the homework - so all I had to do was add some studio magic to it. For me, that’s the best of her - and always has been.”

“They didn’t like Prince’s bikini underwear”: Prince’s support sets for the The Rolling Stones in 1981 are remembered as disastrous, but guitarist Dez Dickerson says that the the crowd reaction wasn’t as bad as people think

“I quickly realised that the order of Eddie’s embellishments is really important to the fans”: Joe Satriani says which Van Halen songs were the trickiest to play on tour with Sammy Hagar