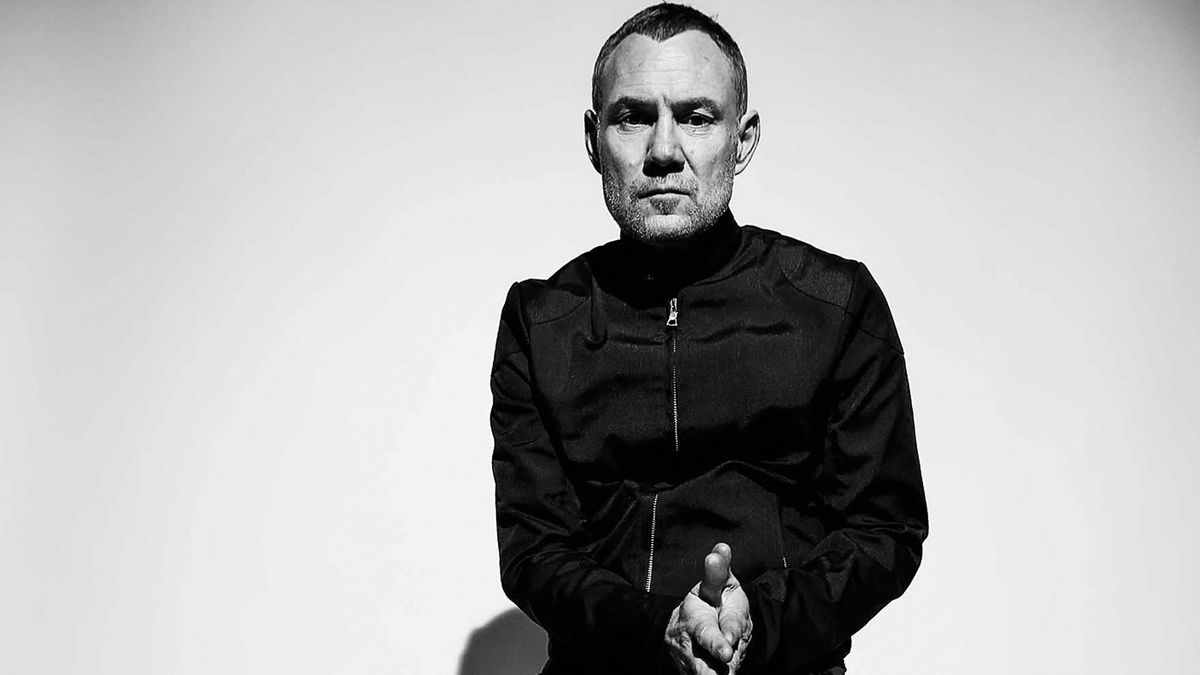

David Gray: “To allow other people in is a form of strength. I’ll work in a way that most find unnerving”

The songwriter goes prospecting for creative frontiers and is reborn anew on Gold In A Brass Age

Songwriting is a brutal art. There’s no practice schedule, no spiritual accommodations, no dietary regime and certainly no lucky underwear that’ll guarantee safe and swift passage for your every musical idea.

Sure, some songs come easy. They’re the exception; you’ve got to be prepared to suffer. David Gray is. But then you get the impression he enjoys it.

Take Tight Ship, from his latest album, Gold In A Brass Age. Here was a puzzle that took 18 months to solve.

“I had a million different ideas and they were all far too pretentious and up their own arse,” he laughs.

As it happened, one line resolved the song lyrically and now it’s on the album. That’s songwriting for you. It takes as long as it takes. Little wonder Gold... was four years in coming.

Written and recorded while touring 2016’s The Best Of… compilation, it was produced by Ben de Vries, whose father, Marius, worked with Gray on 2005’s Life In Slow Motion. It feels like a fresh start. The electronic elements that have long augmented Gray’s arrangements are more experimental, his lyrics more opaque, open to interpretation. But the biggest change is with Gray himself.

It’s taken a while to be free of this [self-]consciousness

For an artist whose career has been so successful that it seems vulgar to mention numbers - we’re talking record sales in the tens of millions - there is the ever-attendant pressure of fame, and this might be the first time Gray has reconciled himself with his status.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“I think there has been a dawn happening within my music and my writing, a sort of lightness of being that’s been a long time coming,” says Gray. “It’s taken a while to be free of this [self-] consciousness, with being this sort of public thing, and things becoming apparently more important because it’s a bigger deal.”

Gray’s songwriting began to evolve during the sessions for 2014’s Mutineers. The most important thing was to be open. Where ideas came from didn’t so much matter as long as he could hear some musical potential. It could be dialogue from a TV show, a conversation overheard on the train, whatever. Gray kept taking notes. Only later would he sift through them to see what chords might work. It’s an almost Dadaistic approach - “cut and paste” as Gray describes it - assembling songs this way was 100 percent practical.

“This is the most important thing about my change of process,” he explains. “I find that going that way round disarms my sense of taste, so I don’t know whether what I am doing is of any interest, or any good, I don’t know how compelling it is as melody or anything else. Only later will I realise the strength or weakness of what I have done.

“So I don’t have the burden of making that evaluation; I’m just working instinctively. It’s embracing the chaos and knowing that how you put it all together will tell a story.”

I’ll work without knowing what I am doing, trying to find lyrics in the studio, in front of other people, singing nonsense, reaching for melodies

For all its more experimental elements, with tracks such as Furthering almost evoking a sense of gentle psychedelia, Gold In A Brass Age is still a work of storytelling. Only it is less direct and more subjective. What Hall Of Mirrors means to you is just as important and valid as what it means to David Gray.

In that sense, you could say the audience is a collaborator after the fact, but other people’s thoughts and ideas were crucial and welcome throughout the writing and recording. Gray’s name is on the sleeve, on the ticket, but to realise his ideas fully, he recognises the value in sharing ideas as soon as he can, or more terrifying still, as they arrive. Full disclosure, no fear: that’s Gray’s credo. There begins the journey. That’s where you’ll find the gold.

“To allow other people in is a form of strength,” he says. “I’ll work in a way that most people might find unnerving. I’ll work without knowing what I am doing, trying to find lyrics in the studio, in front of other people, singing nonsense, reaching for melodies, reaching for chords, just laid bare, ugly and entirely in front of whoever is working in the studio.

“Lots of it is just down to the creativity of the musicians who I work with, or my producer. And we go off looking for mad shit! And sometimes that sounds so good that you get rid of the original idea entirely and just stick with the weird stuff. The production, it’s all another level of fearlessness. You need to realise that none of this is important. You can always go back to it, but what’s the harm in looking?”

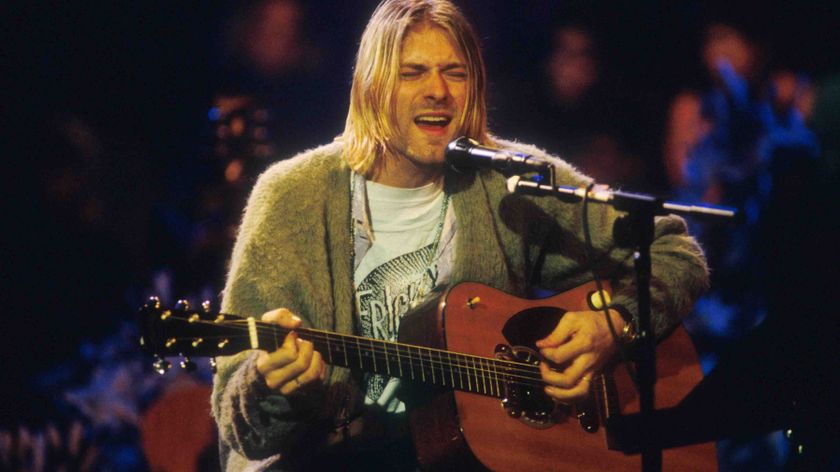

A miracle on Denmark Street

David Gray on his guitars and why his Martin acoustic remains number one

“My default guitar for recording is my 1962 Martin 000-18, which I bought from Andy’s on Denmark Street with my first publishing cheque. It still serves me well. It is the most beautiful-sounding guitar I own.

“I used this funny little Fender. We call it ‘the mandolin’ - it’s missing the sixth string. It’s like a hollow-body thing that I bought 20 years ago. It’s got this quirky little small sound. I’ve got a Fender Telecaster. I’ve got an old Jag from the '60s. Those things both feature, too.

“I’ve always got a baritone at hand; I’ve got a Louden baritone acoustic that they made for me [and] I’ve got an original Danelectro bass. It brings instant character and atmosphere. Every songwriter should have one.”

Jonathan Horsley has been writing about guitars and guitar culture since 2005, playing them since 1990, and regularly contributes to MusicRadar, Total Guitar and Guitar World. He uses Jazz III nylon picks, 10s during the week, 9s at the weekend, and shamefully still struggles with rhythm figure one of Van Halen’s Panama.