Dave Clarke discusses the making of his latest album and gets his geek on

With nearly 30 years in the industry, the now Holland-based DJ/producer returns from a 14-year studio album hiatus

Signed under the pseudonym Hardcore by legendary Belgian techno-rave imprint R&S Records in the early '90s, Dave Clarke’s career ignited in 1994 with the techno trilogy Red (Bush Records). This was followed by the more expansive debut Archive One, an album sparkling with hip-hop and acid techno fusions.

By the mid-'90s, the often outspoken DJ and producer was remixing major acts including The Chemical Brothers, New Order and Depeche Mode. As well as being one of the most in-demand DJs on the circuit, Clarke started recording the weekly radio programme, White Noise. Based in his adopted hometown of Amsterdam, the show recently surpassed an incredible 600 episodes.

Clarke signed to Skint Records for his second studio album, Devil’s Advocate (2004), and, following a production break, collaborated with Jonas Uittenbosch (aka Mr Jones) under the name _Unsubscribe_. Revitalised by the diverse array of remix contributions featured on the remix album, Charcoal Eyes (2016), Clarke then headed back to the studio to record his long awaited third full-length, The Desecration of Desire.

How has living and working in Amsterdam influenced your career, both musically and cerebrally?

“I think I needed to come here. I can’t explain why or what happened, but I don’t think I could have been who I am now without being here. It’s opened me up to a different kind of living, less based on status and more on social life and having so much art and inspiration on my doorstep. I don’t want to sound like this bitter guy slagging off where he came from, because I am very happy about growing up in England and how it shaped me towards the beginning of my journey to Amsterdam, but when I go back to England now I do feel like an alien that doesn’t really belong anymore. I’m definitely a European as opposed to an Englishman, especially after the Brexit vote.”

Desecration of Desire comes 14 years after Devil’s Advocate. Why such a long gap?

“On a personal level, my life changed quite dramatically, and that even affected me when I was making the Devil’s Advocate album. I had to book studio time to even get into my own studio and make music. I moved to Amsterdam and I had to take a look to see what was happening in the world of music recording. I’ve never been the most prolific of artists anyway, but so much was changing and I just wanted to see what was going to happen. When I first started, there was the internet - and if you were lucky and you had a good connection and five hours to spend, you could send a single 16-bit 44.1 Wav, which was considered a good result.”

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Is this when you started to get back into the world of software sequencing?

“Well I had to get back into it, and I spoke to my friends at Focusrite who introduced me to someone who was going to teach me Ableton. Although I enjoyed the flexibility it gave you and what you could do with samples, I didn’t really like it - it just reminded me of C-Lab Creator. It was a jamming tool, and a brilliant one at that, but I couldn’t write with it and I was still using Cubase 3.5, which I didn’t really like any more.

“Then I started using Logic with Mr Jones, and realised the GUI was similar to Cubase. Throughout my journey of making music with Jones and remixing other people, Logic became much better and more reliable. Although the journey from 9 to X was a bit painful, the whole program is fully 64-bit and everything you could wish for is catered to. I think I was still waiting for that while working in an environment where I wasn’t constantly distracted by program crashes that I couldn’t really control.”

The new album isn’t a straight-up techno record; it’s much more expansive than that...

“Yeah, I listen to so much music at home, and I always did, but I never had the ability to follow those dreams with the budget I had, in my mind at least. Listening to so many different types of music, Henry Rollins podcasts and BBC Radio 6 Music in Amsterdam, I got really inspired by what was out there. It just wasn’t in me to create another techno album. To me the whole point of techno is to be an effective tool on the dancefloor, but then an album just becomes a collective toolbox. I wanted to have emotion on this album. Obviously, this had been brewing in me for a while and I wanted the album to be like a book, written in chronological chapters. Within the tracks, there are various different emotions related to my life - it’s a weird, abstract audio diary of the past two years.”

Having finished the album, are you surprised at how it’s turned out and can you pinpoint those subconscious influences from the past?

“I don’t know about influences from the past - they’ve always been present. Anyone who makes music that is honest has that; it’s what shapes you. The influences would be all the guests I have on it. I always wanted to work with Keith Tenniswood, for example. He’s a past influence and someone I always looked up to. It’s the same with Mark Lanegan, whose voice is so deep, expressive and beautiful. Then there are Anika and Gazelle Twin - who, from a vocal performance perspective, are quite incredible, and Louisahhh, who has such a characteristic, sexy, sassy voice.

“I think it’s dangerous to reminisce about the past. There are subtle past references embedded within your DNA, but don’t pull upon them to the point you become a pastiche.”

Nevertheless, remixing John Foxx’s Underpass on last year’s Charcoal Eyes remix album must have been a real joy for you?

“It’s a scary joy because that record has been part of my life ever since I was seven years old with my Ferguson tape recorder recording the word ‘underpants’ over it. John Foxx is a legendary person. He could have been in the Sex Pistols, apparently, but he was in Ultravox and to be given the original pieces was an honour. None of it was quantised, so when I was doing my remake, I wasn’t going to quantise it either. He wrote me a lovely email afterwards, too.”

When you take apart a classic track like that, is there a danger of it losing its mystique because you’ve seen the process behind its creation?

“I don’t know if you see the process, but the first time I was blown away by that separation was when I was at DMC in Slough and I heard Paul Dakeyne in another room playing the acapella of Michael Jackson singing ‘shamone’ on its own. For a second, it destroys the memory, but then you have to look past that and treat it with respect. Don’t overanalyse, which is weird for me as I overanalyse everything.”

Going back to Cover up my Eyes and Gazelle Twin’s heavily processed vocals. What are some of the techniques you’re using?

“I wrote the track before I gave it to Gazelle Twin to work on and I had an idea of how I wanted the vocal delivery to be, which was quite robotic - very staccato. I won’t do more than four vocal takes as I don’t see the point. If you haven’t nailed it by then you’re not going to, and if you have too many opportunities, why digitise it to the point where you suck out all the humanity? So the vocal went through a lot of analogue processing using a relatively good Blue Mic in a clean environment. I couldn’t tell you the effects chain I would have had on that. What I can tell you is that I wanted to push her vocal inside the skeleton of the track, so that it wasn’t sitting on top but weaving throughout the bones of it to create quite an architectural delivery. I had to make sure there weren’t any phasing issues because it was processed quite heavily on the mids and sides, so I was constantly checking mono, the phase reverse and looking at the Jelly meter on the DK audio.”

I refuse point blank to do sidechaining. I’m not having a go at anyone but personally I see it as a lazy way of making music.

What’s responsible for that brutal synth sound at the start of the first track, Exquisite?

“[Laughs] You know what? You’re going to have to ask me these questions via email later so I can find them for you. I do know the synth sound you’re talking about, but at the time I had 12 cores of UAD processing on my Mac and it was hitting 95% just for that synth intro. I remember I had to mute a lot of the plugins after I finished that intro just to free up DSP going forward. I only ever bounce audio for remixes because I don’t feel comfortable doing that and I like to have the flexibility of being able to move the plugin in a chain somewhere else and EQ without having it printed.”

The album’s beautifully produced. Do you put that down to your preparation of sounds or how it’s mixed?

“When I was reading a book, Great British Recording Studios, I realised that I’d taken on board the British way of recording: which is to produce as you go along and do volume, balancing and panning afterwards. I only did it once on this album, but I refuse point blank to do sidechaining. I’m not having a go at anyone, but personally I see it as a lazy way of making music and I much prefer to craft the EQ visually and audio-wise - although I only really felt I could do that once I’d replaced my monitors with ATCs. Only then did everything start to gel and I could actually hear the definition on reverb trails in a way I could only dream of before.”

It sounds like you had a bit of a speaker technology awakening?

“Once you’ve found the right speakers you stick with them forever, but when you move studios, sometimes those speakers are not going to work. I started a new studio on a boat in Amsterdam and I put Tannoys in there as homage to my father who used to listen to Tannoys at home. I mixed Archive One on a pair of second-hand Mercury MS20s that I bought for £120 and sprayed the horrible wooden exterior with Ford Cortina blue, put some gold dust flakes on them and lacquered it all together. The way that I work, everything in the studio has to work together, even the visual monitor placement, because it’s a reflective surface. I tried desperately with these Tannoys that I bought here in Holland but couldn’t get the clarity, even despite the fact that they had 50kHz super tweeters.”

So the boat was the problem?

“All of a sudden, I realised that dual concentric wasn’t working for me on the boat, even with decent cabling. So I tried these ATC speakers, put them on the right sides, referenced Steve Wonder’s Songs in the Key of Life and every time the fucking cowbell came on it rattled my cranium. So I thought, ‘Shit, that’s a shame’. I suggested swapping them the other way around, but the guy in the shop said, ‘You’re not really supposed to do that’.

“What I learned from learning how to fly was, if it looks like shit it’s generally going to fly like shit. That’s why I was never a fan of Cessnas and I preferred Pipers, because it looks like a decent aeroplane and the wings are in the right place. Basically, the ATCs looked like shit in that position, yet, bizarrely, when I flipped them round they sounded perfect and looked better. The stands I had them on were not robust enough, so the other 5% was about fitting Towersonics. And I still believe in cabling if you’re going to take the analogue route, and the lovely people at Oyaide had given me some beautiful cables wrapped in carbon fibre with palladium connections and glass-filled bezels, which again made a difference.”

Do you compose entirely by ear? And do you feel it helps to have an intrinsic understanding of how sound behaves?

“I think there’s a benefit if you’re working with live acts and entertaining A&R people, but the one thing that’s always confused the hell out of me is, when I see a picture of the Abbey Road studio and the B&W speakers are on the floor with half of the cones blocked by a mixing desk and I’m thinking, how the hell can that even sound good? Obviously, it does. Abbey Road know what they are doing, but it doesn’t make sense that half the speaker is masked by a meter bridge. Yes it’s great to understand flutter or standing waves, but I just need one focus point, where two ‘flames’ reach me, which is where I’m sitting. I’ve also got a great mastering engineer, Matt Colton, who also works with ATCs. I trust him to translate anything that I’ve missed out.”

I know you have a huge variety of compressors, too, which some may think is unnecessary - but it’s obviously important for you to utilise multiple sonic characteristics.

“It’s important because, for me, a plugin compressor is still an effect. There’s no physicality and that can be useful to have fun with and crunch the hell out of stuff, but I don’t have any analogue synths at all - I just put all my Arturia synths and other soft synths, like GForce, through analogue compressors, EQs and an analogue desk.”

Many artists will use analogue hardware synths because they feel they offer something that can’t be recreated in the box. But you feel a soft synth going through hardware compressors can still match that?

“I still don’t believe you can use a plugin to authentically replicate a compressor, because they’re inflexible and you get too used to automation of effects. EQ plugins are stunning, brilliant and sometimes usefully surgically, but I think it’s very important to use analogue for compression. I’m a fan of half-speed mastering and I think it makes a real difference. But it’s really about what works for you and what you want to say. I can’t work on an aeroplane with a pair of Bose noise-cancelling earphones and make an EDM hit, although some can; I want - and need - to be in a dedicated studio and have the ability to throw my phone out the door so I don’t Facebook all the time.”

Then there’s the tactile aspect of hardware, but we know you find using a Kensington trackball mouse can be equally intuitive and speedy…

“The trackball’s amazing. You can do chord button programming, which is basically making macro commands that will keep your workflow speedy without touching the keyboard; and sometimes when you go to someone’s studio and don’t have one, you realise what an important tool that is. Having said that, I’ve now invested in a Softube Console One MKII and, again, that’s opened up my workflow. I’ll load some of the UAD EQs into the console itself, and I do miss the GUIs, but it’s a very workable, cocoa-style interface. I only bought it recently, but I’m mixing someone’s album right now and it’s a brilliant go-to. It reminds me of the flexibility I use to get with my old Yamaha O2R mixer, where you can see everything going on in a channel.”

You have about 800 plugins to choose from, but do you believe in limiting yourself to avoid the paralysis of choice?

“No, because I commit very quickly and I don’t overthink it. If I need an EQ, then I go to whatever is my favourite one at that moment and I don’t wonder what it will sound like through this or that EQ. I think I have 1,250 plugins now. One of the good things that Logic caught up with on Cubase is that you can finally have your own plugin folders, so now I can have DC’s favourite musical EQs or DC’s favourite surgical EQs and locate them really quickly. I can also have my favourite plugins or new plugins this month, and eventually I end up with around 80 that I always go to.

“Sometimes, I might have a bored moment when I’m watching Dave Pensado on TV and think, ‘Oh shit, I forgot about the Soundtoys Boiler’, and that’s fun - and it should be fun. I also usually look forward to going to the IBC (International Broadcasting Conference) and catching up with my friends from some of the magazines to have some ridiculous, and deep, nerd talk.”

I commit quickly. If I need an EQ, then I go to whatever is my favourite one at that moment… I have about 1,250 plugins.

Give us an example of the kinds of things you’ll pick up on during a conference?

“Well, I did see an amazing desk last year that had fader channels light up with a colour of your choice. I think it was from Studer, and you could group colour everything, which made a lot of sense. I thought it would be rather cool if I could learn that for Logic and, for example, colour all my bass sounds in a shade of red on the desk. But, to be honest, most technological innovations these days are very subtle and happen online, and there are not that many music shops around.

“I actually tried the Roli Seaboard, but then I quickly realised that there was no way in hell I could ever use that. Don’t get me wrong, it’s a wonderful design, but with my OCD, it’s like, ‘Oh my god, it’s made from a really weird silicone, it’s going to ingrain dust and feel horrible to touch’.”

Are there any other plugins that you are a big fan of these days?

“I’m a massive fan of Arturia soft synths and some of the Rob Papen ones. The GForce Oscar is a beautiful synth. And UAD, of course, because they have these really old but efficient SHARC chips that can handle the DSP - so you can use plugin after plugin after plugin and not have to worry or keep an eye on the DSP in Logic on the computer. Their plugins are also very good quality, with very little evidence of problems or crashes because they’re so serious about it.”

You had quite a serious car accident last year; did that change your philosophy on life?

“Yeah, it changed my philosophy massively, because it was a really lucky escape. The car could have flipped on the roof - or been hit by a lorry. The fact that I felt pretty let down by what happened afterwards also opened my eyes, as well as the fact that I’d been working so hard for so very long - as many of my compatriots are doing all the time - but then you start to wonder exactly what you're doing it for. I still have flashbacks every time I’m on a mode of transportation. I don’t have palpitations or panic attacks, but I’ve lightened my schedule to doing more recording and less on the road. It’s definitely changed my outlook and I still get emotional about it, but, obviously, it could have been far worse.”

The Desecration Of Desire is out now. Check out Dave’s official website for more info and tour dates.

Future Music is the number one magazine for today's producers. Packed with technique and technology we'll help you make great new music. All-access artist interviews, in-depth gear reviews, essential production tutorials and much more. Every marvellous monthly edition features reliable reviews of the latest and greatest hardware and software technology and techniques, unparalleled advice, in-depth interviews, sensational free samples and so much more to improve the experience and outcome of your music-making.

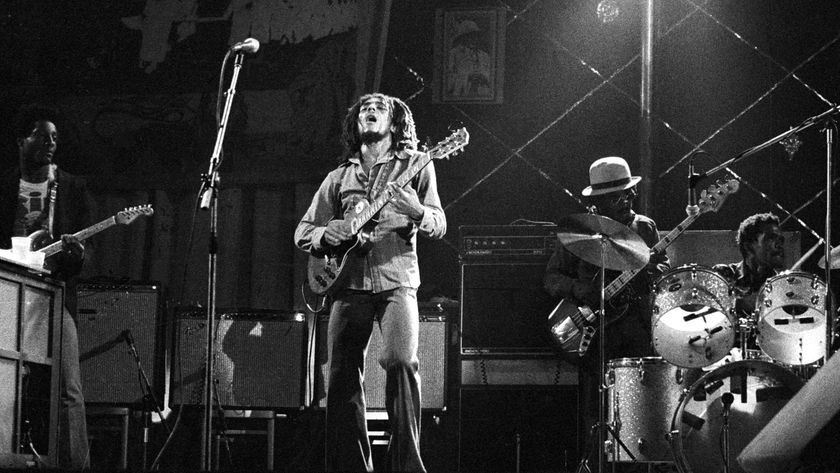

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track

“Part of a beautiful American tradition”: A music theory expert explains the country roots of Beyoncé’s Texas Hold ‘Em, and why it also owes a debt to the blues