Danny Daze: "If I want a low-end analogue sound, I’ll turn to my Moog Voyager, and if I want some high-end crispy stuff I’ll reach for an FM synth like the Ensoniq Fizmo"

After canning two albums, Miami-based DJ/producer Danny Daze delivers a 92-minute concept LP, truncated for VR headsets. Danny Turner finds out more…

Heavily influenced by the Miami bass genre, Danny Daze is famed for his eclectic DJ sets and a love for releasing hard, driving techno, electro and disco with an experimental IDM lean.

Founding the Omnidisc label in 2015, he has continued to redefine his role at the cornerstone of Miami’s diverse dance scene, yet despite a couple of aborted attempts Daze also harboured the ambition to step out of the box and create a concept album that moves well beyond what he’s best known for.

The pandemic finally allowed Daze the time to focus, resulting in a furious period of creativity during which he created 100 tracks, swerving from abstract IDM to booming bass music, absorbing influences past and present.

Daze then honed the tracks down to a 90-minute continuous concept piece titled BLUE, designed to be listened to as a singularly immersive album. Fully invested in his newly creative approach, Daze has also created an abridged 33-minute audio-visual version in full Dolby Atmos for virtual reality headsets.

Last time we spoke in 2015 you said you were going to release a solo album sometime around February 2016. Obviously, you had a change of heart at some point?

“I actually had an album completely done in 2013, canned that and pretty much had another one finished for release in 2016 but it wasn’t 100 per cent exactly how I wanted it to be either. In the end, I decided to disperse the tracks to EPs. I really wanted my first debut album to be able to tell a story in parallel with what I consider an album to be, which meant having a concept rather than just presenting 10 dance tracks.”

It’s said that your debut album BLUE has been 24 years in the making. Would you agree that this is a culmination of everything you’ve absorbed since you became a producer/DJ?

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“We joke around and say that it’s been 24 years in the making, but there’s actually quite a bit of truth behind that. The album took around three years, but the original tracks were truncated down from 100, which really was a culmination of 24 years of my experiences as a DJ and producer, LPs I’ve listened to that meant a lot to me and just trying to figure out how to grab a listener in a way that’s not related to dance music. BLUE has IDM elements, but also has an old-school DJ Techmaster P.E.B. kind of sound – he’s the guy who used to do Miami bass, super subwoofer-driven car audio stuff.”

Three years in the making takes us back to the pandemic. Did that period give you the time to finally focus on a more expansive body of work?

“It automatically gave me the time and peace to think and subsequently produce 100 songs. I started before the pandemic, but that period also includes the planetarium show, so I had to figure out exactly what to release. Knowing that, I needed to truncate those 100 tracks down to something that could tell a story rather than just focus on the bombs. I basically wanted to create a 92-minute album that would be a movie without images.”

When you started making all of those tracks, was the initial idea to just play with ideas, see what you had and distil it all down?

“The fact that I had a lot of time meant I could solely focus on getting into the studio every day and record for 16-18 hours. I was really digging back to where I started, which was IDM, electro and Miami bass music, and I wanted to have a lot to select from in order to create a story. It was really about me thinking more like a movie director that might want an actor to do multiple takes or work from different scenes that typically don’t make a cut.

“If you try to make 18 songs thinking that these are going to be exactly what you want, you’re limiting yourself in terms of telling the best story possible. That’s why a lot of the tracks are now being slowly released in different places. For example, I just released an EP on Schematic Records because four of the tracks didn’t make the story as they were much more club-oriented.”

When did you decide to partition a number of tracks to create what you could finally call your debut album?

“I started making the songs in 2019 and by the end of that year, I found myself making music specifically for a concept album. By that point, I felt I had released enough music that had departed from the dance stuff people knew me for or from DJ sets that weren’t exactly related to fast-paced dance music.

Over the last few years, Miami has been put on the map by a lot of the younger generation, which has made me feel a lot more connected

“I finally felt comfortable enough to move forward and produce an album that I knew could be released and I no longer had to travel at the weekend only to forget what I’d been working on when I came back and then have to readjust and reset everything. Basically, I could just dig in and become a studio rat, which was a pretty interesting experience because I’d never had that sort of time or the presence of mind to go full force.”

You’ve spoken before about struggling to adapt to living life as a global DJ. Is that still the same today?

“Back in the day, I felt like I was the only person in Miami travelling and doing shows. I never really felt accepted or included in anything – I was just this guy that some people knew because of my name. Over the last few years, Miami has been put on the map by a lot of the younger generation, which has made me feel a lot more connected.

“Now, I feel super-comfortable playing two really solid shows a month rather than chasing this thing that I see a lot of unhappy touring DJs doing. I’m hoping an album like this puts me on a different route and allows me to do something completely different to DJing at a dark club or festival.”

You’ve claimed that your studio is like a spaceship inside a forest. Presumably that means a lot of plantation and trying to steer away from creating music in a sterile environment?

“Precisely – I also like collaborating, and not just with electronic artists but rappers too. I’m currently producing a girl from Miami called La Goony Chonga, MJ Nebreda and some others too. When people visit my studio I want them to look around and think, I’m not used to this – it has an ‘anything goes’ energy. The studio’s got an ambience with roses hanging off the roof, mushrooms and leaves everywhere within a full-on Dolby Atmos system inside the back of a house in the middle of the Cuban part of town. There are no windows here either, so it’s very easy to lose track of time.”

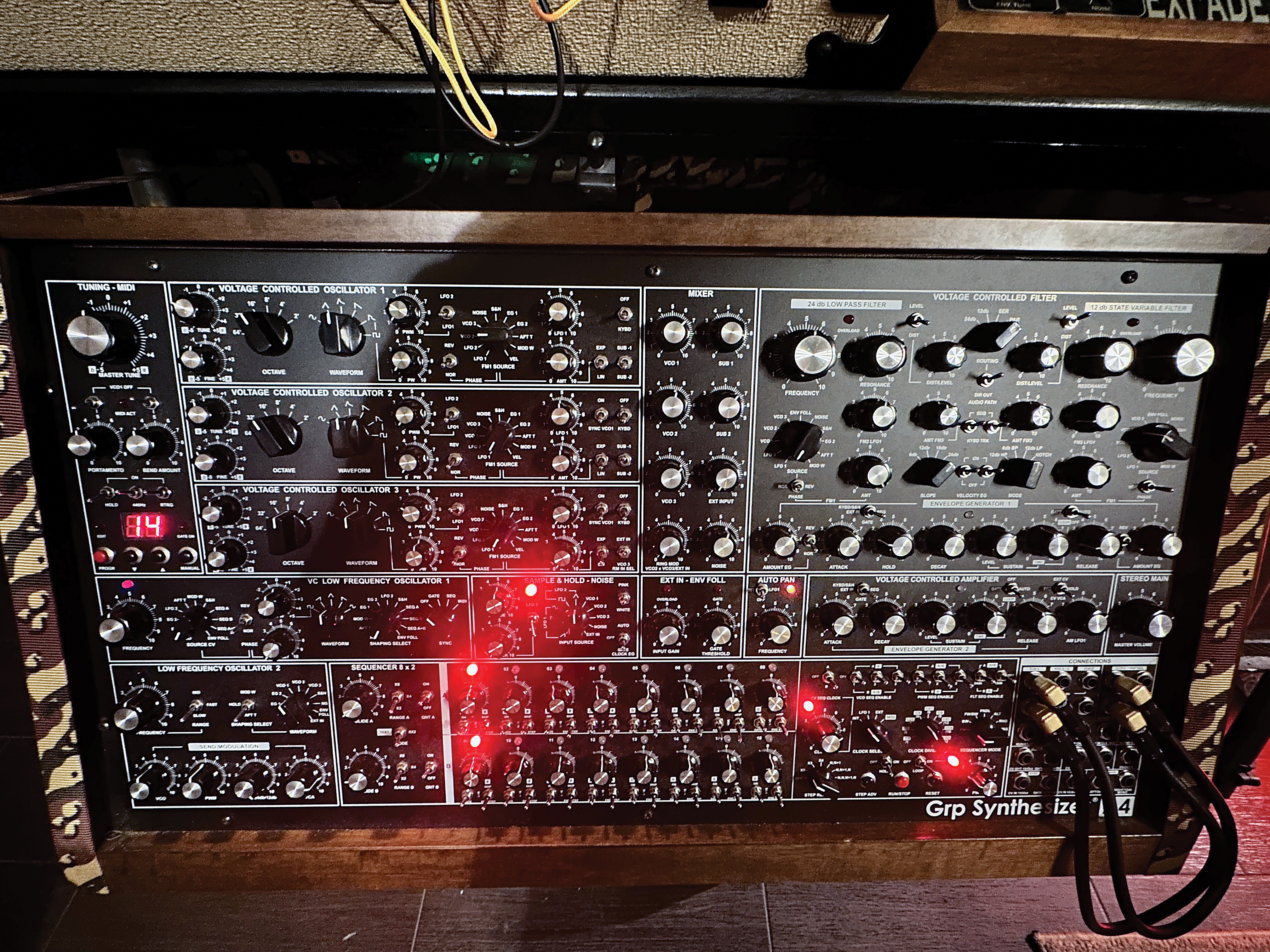

What gear did you use while initiating tracks for BLUE?

“What’s changed over the years is that I’ve removed some of my equipment and I’m now more focused on what gear works inside a specific frequency spectrum or synthesis layer of whatever I’m trying to achieve. If I want a low-end analogue sound, I’ll turn to my Moog Voyager, and if I want some high-end crispy stuff I’ll reach for an FM-type synth like the Ensoniq Fizmo. I also love how the Eventide H9000 allows me to absolutely destroy whatever I run through it and I do like a lot of the new plugins that are around today.”

What specific ones do you find appealing and why?

“I’m very much into DSP processing, re-rendering, mangling sounds and making something out of harmonic parts by re-recording, time stretching and reversing stuff because you get a tonality that you can’t really achieve from sequencing alone. I love it when you can sample a mistake and make a whole new melody out of it, so a lot of the album was about running stuff through the H9000 or software like Output Portal or Arturia’s Efx Fragments.”

Are you just using Ableton for sequencing or have you delved deeper into that too?

“I mainly use Ableton for recording but it’s obviously its own monster. I’ll use a lot of its MIDI capabilities, for example, recording stuff live with an arpeggiator, running it through a Scaler and running that back through Ableton’s note lengthener plugin before sending the MIDI notes out to my Sequentix Cirklon hardware sequencer.

“I just love experimenting in that way, even if I have absolutely no idea what I’m doing in the studio. I only really know if I’ve found something that works when I’m pasting the last pieces of the puzzle – if you asked me to start sending CC messages, I’d have to go read the manual.”

It sounds like not knowing what you’re doing is the partly the point?

“I purposely try not to menu dive too much because you end up wasting time. Especially with FM synthesis because you turn one knob and everything gets messed up. I can honestly say that I probably only understand 15-20 per cent of what my Cirklon does and have deliberately kept it that way. If I really need to figure out how to go into reverse or use pendulum mode then I’ll start looking into it.”

The track Fukushima has these lovely Japanese-style melodic tones. Did the tones inspire the title or did you already know the theme behind the track that you wanted to make?

“All the notes were played on black keys on a piano, which usually has that sort of Asian vibe. At the same time, I was listening to or influenced by Susumu Yokota. I forgot when he passed – a few years ago now, but I started the track right around then and Fukushima is probably one of the more DJ-playable tracks on BLUE. Another goal with the album was to try to focus on the different parts of the world I’d travelled to and get influences from those places.”

Did you find other influences popping out? Communication, for example, sounds very Kraftwerk-influenced and Antigravity Machine sounds very atonal and Aphex Twin-sounding?

“There’s a crew in Miami called Phoenecia, who also go by the name of Soul Oddity, which really influenced me when I grew up breakdancing. If anything, their album Brownout and Roni Size & Reprazent’s New Forms really pushed me. When it comes to Aphex Twin, I actually don’t know too much about him. People might hate me for that, but although I was always into the Miami IDM sound and that crew were definitely into Aphex, the only thing I knew was his album, Selected Ambient Works.

“I wouldn’t want people to think my music is a cheap version of Aphex, Autechre or Squarepusher though; my influences remain heavy on the bass side and come from the competitions that I used to take part in back when I had subwoofers in my car.”

Tell us about the different variations of BLUE and why you’d prefer people to listen to the 92-minute continuous version?

“We broke the album down to 19 tracks, but that’s just for DJs, the continuous album is the way it’s supposed to be heard and I was actually contemplating only releasing it as a 92-minute file. People around me suggested I break it up so people can play the tracks individually, but on Spotify and every other streaming service, the album will transition from track to track. I spent a lot of time working on those transitions, especially for the Dolby Atmos version where I had the chance to enhance the feeling of there being a ground loop that goes around your head.”

The album’s beautifully produced and mixed and the sound separation is quite exquisite. Does that require painstaking amounts of time and patience or, again, does it go back to your experience making records?

“For me, it’s all about knowing where things will fit in the frequency spectrum. If there’s a sound at 12k or up, I know that in order for it to stand out I need to remove a lot of the middle frequencies and make the song more about the contrast between the low and high end. That was especially important in terms of the album transitions, because those parts had a lack of sound.

When producing the tracks, I’d sit down, listen to them over and over again, meditate and try to figure out what they would need, and there’s no better way to do that than by putting on a 180-degree, 3D, 8K helmet

“I’m sure my years of DJing and understanding what works in terms of being minimalist and maximalist is subconscious, but I’ve always had that in me because of the car-based world that I was so into. There’s an act called Dynamix II who released an incredible album called Coloured Beats in the ’80s that’s minimal and very well mixed with a lot of bass, so I wanted to emulate that and ensure that when people listen to this 92-minute soundscape in the stereo field they can fall into all of the panning and mid-side EQing.”

So what gave you the idea to create a truncated 33-minute audio-visual version of the album to be shown in planetarium-type environments?

“The 33-minute truncated version does not consist of every single song, I just wanted to tell a different story visually – something that would be mixed in surround and look good. I always had a vision in my head of what I wanted when it comes to putting on a visual show. For me, having an artist stand in front of a beautiful screen is distracting and doesn’t really make sense.

“When producing the tracks, I’d sit down, listen to them over and over again, meditate and try to figure out what they would need, and there’s no better way to do that than by putting on a 180-degree, 3D, 8K helmet, which is what a planetarium is because your peripherals are completely engulfed and there’s no artist standing there in front of a two-dimensional flat screen.”

Can you tell us a little bit more about your process behind creating this type of audio-visual experience for the listener?

“I funded the whole thing myself before I even had the green light to get into a planetarium. At first, I thought we’ll just have this as a VR headset, but as soon as I had a pretty decent version of the album in that format I showed it to people at The Frost Museum Planetarium who gave me the ability to test it. When they saw it, they thought it blew what they had out of the water, which encouraged me to work on it more until we finished the final version in September.”

What visual themes have you gone for to complement the album?

“Both with the 92-minute audio version and this 33-minute visual piece, the album has a kind of index and story to it, but I don’t want to talk about that too much because it might persuade people to interpret the album in a different way. Essentially, it’s just about how life is represented to me.”

When did the idea of creating a Dolby Atmos mix come to you?

“I essentially wanted a conceptual album where people could just sit down, listen to the entire thing and feel like they were in a movie theatre. Over the past 18 months, I must have had 150 people come to my studio to listen to the album and I blindfolded them to help them fall into the experience. The long-form version of the album has given me a full 360 degrees to work with, but with Dolby Atmos, the element that was once sitting between the left and right could now go centre, up, left, right or behind you, and that’s what creates a massive difference.”

Is it a problem that most people do not have access to Dolby Atmos-related technology?

“Sure, the technology is not available to everyone yet, but I assume this will happen within the next two-to-three years. They’re already coming out with Dolby Atmos sound bars that have directional speakers pushing sound to the ceiling and there’s a big difference between the stereo and Dolby Atmos version.

“When you listen to it on headphones from Apple Music, for example, you’ll feel that the stereo spread is much wider. It’s more about future-proofing the album so it can be a standard that people might look to as and when the technology catches up.”

Did you spend time adapting sounds to get the most out of what Dolby Atmos brings in terms of sound design?

“A lot of people can make the mistake of thinking that Dolby Atmos means you should start spinning things around your head or have sounds bouncing all over the place. For me, it’s more about the proper placement of sound, moving objects and putting them in a wider space so you can focus more on the proper left and right stereo channels or place something in the centre in a way that’s tasteful.

“The tracks were already quite spacious, but I was able to spread those elements out even more and add elevation, so rather than a song being at ear level it could also be introduced from the top down. The only song I went kind of crazy with was Communication, because it already had things popping out everywhere.”

Did this process mean redesigning your studio to be fitted for Dolby Atmos?

“Oh yeah, I had to take my entire studio apart, which was a pain in the ass. I had to place every speaker where it would best fit and went through one set that wasn’t big enough so I had to go through the whole process twice. That was a lesson learned – if you’re going to kit your studio with Dolby Atmos, do it right the first time.”

Doesn’t the system require about 20-30 speakers or is that only for cinema?

“You can put in as many as you like. I have a 7.1.4 system, which comprises 12 speakers, but you can go 9.1.6 and I think the Sphere in Las Vegas has thousands. That’s what I like about Dolby Atmos – it’s kind of like a vector file for audio that just expands to whatever the system is.

I love the technology and have even had the Dolby Atmos people hit me up as they weren’t sure how I was able to blend a 92-minute full Dolby Atmos file while only working with 128 channels of audio

“I love the technology and have even had the Dolby Atmos people hit me up as they weren’t sure how I was able to blend a 92-minute full Dolby Atmos file while only working with 128 channels of audio. They gave me some suggestions but also asked me some questions, which was pretty cool and we’re now talking about whether I can showcase BLUE in their New York studio.”

Presumably, you can also hire out your studio as some sort of Dolby Atmos facility?

“I’m actually releasing an album by Vril on Omnidisc that will be mixed down in Dolby Atmos, so yes, it allows my friends or any artist I release to try and be a lot more experimental and conceptual. I’d love to be able to provide music coming from the label for movies or render a file in Dolby, so hopefully this will send a message out to artists that there are labels willing to go that little bit further.”

We understand some additional AV content is being made for an app?

“Now that we have the file, I’m working on creating an audio-visual version of the album as an app. That process has been a little more difficult than I expected because completely new code needs to be written for the Apple Vision Pro mixed-reality headset. Ultimately, I want to push this out as a very simple downloadable app where you can sit down with your VR headset, press play and just go on a 33-minute ride.”

What’s coming next for you in terms of future productions and projects?

“I’ve started two different aliases – Danny from Miami, which is about producing music for other people, and D33, which is a bit more laid back and suited to being played after-hours. For the Danny Daze stuff, I’m already working on another album and because I still have a lot of unreleased music, some of which will be repurposed. I really like where my head is at now.

“These days, it can seem like everybody wants to be a famous DJ playing 150bpm techno, but for some reason my calling is to go in the complete opposite direction. I’ve always been that way because it allows me to keep my creative juices flowing. Although I’m still making dance music as Danny Daze, I need something to fight against, and I’d love to get into the movie world and potentially score.”