The Crystal Method: "Even though they're unpredictable, I really wanted to get back to plugging in my old synths and analogue gear"

Scott Kirkland of The Crystal Method opens up the doors to his studio for an inside look at the gear behind his new album, The Trip Out

Formed in Las Vegas in the early ’90s by Scott Kirkland and Ken Jordan, electronic band The Crystal Method pioneered the big beat genre and planted a signpost for electronica in 1997 with their platinum-selling debut album Vegas. Alt rock/electronic crossover albums such as Tweekend and Legion of Boom followed, alongside headline shows at EDC, Lollapalooza and Ultra Miami, while their music has appeared on over 100 film, TV and video game soundtracks.

However, in 2017, Kirkland was surprised to learn that Jordan had decided to retire from making music, leaving him to continue the project alone. Somewhat inspired, Kirkland’s cinematic solo outing The Trip Home saw a recalibration of The Crystal Method sound – a release that is now followed by The Trip Out, which further develops his newfound sense of freedom through a melting pot of electronic music styles and collaborations.

Having worked alongside Ken Jordan for 25 years, how did his departure from The Crystal Method affect your state of mind?

“Ken came to me in 2015, saying he was pretty much done with music and wanted to move down to Costa Rica with his wonderful wife to be more eco-conscious, which didn’t really leave a lot of room for things like keyboards and drum machines. It wasn’t like there was any animosity – he gave me his blessing to continue with The Crystal Method and made it really easy for me to buy him out of the studio.”

Working with a partner inevitably means compromise. From that perspective, was there a positive side to continuing on your own?

“Every day I was in the studio I had one person to make happy, so I started looking on it as an opportunity to do things in a different way. Ken would come in and tell me whether something I’d worked on was cool or he wasn’t feeling it and we’d move on.

“Now there was an opportunity to work in a different way or collaborate with other people. That was refreshing, but there were many moments where I’d find myself wishing I had someone that I knew as well as Ken to bounce an idea off or tell me something was shit before I spent another 20 to 30 minutes working on it.”

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Have you found a replacement or had to learn to be more self-sufficient?

“My long-time manager has always had an understanding of the band and its history, but six to 12 months after Ken left, I reconnected with Glen Nicholls from Future Funk Squad. We’d done a couple of things years ago, so he came over to the States and found that we could throw ideas off each other.

Chemical Mentalist started out with me spending a few days going back to basics with a bunch of old analogue synths and the Big Muff

“I spent a lot of time working with Glen on the previous album, The Trip Home, but there are other people like Danny Lohner (ex-Nine Inch Nails) and Tool’s Justin Chancellor who I can send a WAV file to in the middle of the night if I want to get feedback. I don’t get too dejected when I’m working on something that doesn’t pan out; those ideas often come back around to fortify a track or spark a new collaboration.”

Your latest album The Trip Out follows The Trip Home in 2018. In what way are the albums interconnected?

“The Trip Home was a soundtrack to a movie you’ll never see – a stylised, futuristic look at how The Crystal Method was between albums like Vegas and Tweekend. When Glen and I worked on it we had 12 to 14 tracks in various different states that fit that narrative and a few that had a lot of potential but didn’t fit.

“We immediately thought of making a companion album called The Trip Out, but then I got busy on the road and the pandemic hit so the idea drifted away, although I did use Friction and Let’s Trip Out from those sessions. The inspiration for the album changed to a theme of us having been at home for so long that it was time to get the fuck out, so The Trip Out title still seemed to make sense.”

Nearly every track is a collaboration of some sorts. Are they mostly lyrical collabs or did you take the opportunity to co-produce?

“Some tracks were directly re-energised by working with people that I met during the process. For example, Mark Evans is a producer that I worked together with on the track House Broken and we thought it needed a vocal so we found Naz Tokio.

“For Chemical Mentalist, I’d stemmed the track out and started spending time on it before Mark introduced me to Wenzday who has a more modern, bass style. When she came in to hear the stems she got really excited and came up with some great ideas to help make it a driving, mid-tempo track. When I find someone that I get along with I tend to go all in and follow that journey to the end.”

Chemical Mentalist is very grid-like in its construction and its midtempo allows you to study all the sounds…

“I work in Pro Tools and dabble in Logic a bit, but that track was all done with Wenzday in Ableton. It actually started out with me spending a few days going back to basics with a bunch of old analogue synths and the Big Muff and Ibanez distortion pedals to make a lot of those big, growling bass sounds.

We were contemplating bringing a vocalist in but found so much acapella content to play with in Splice that we decided not to

“Wenzday then had a lot of ideas about tightening it all up and giving those sounds a really regimented, grid-like feel that still sounded funky and rhythmic. We had a lot of fun playing with that 100bpm tempo, which is fascinating because it enables you to create something that’s driving but, as you say, gives you the space to play around with lots of sound elements without them all being on top of each other.”

The vocals sound quite heavily detuned. Do they belong to Wenzday?

“The vocal is actually based on found samples. We were contemplating bringing a vocalist in but found so much acapella content to play with from different sources like Splice that we decided not to. The main lyric is based on four phrases put together to make it sound like the words ‘chemical mentalist’. We thought of replacing that too, but after a while it just seemed to fit the style of the track.”

It’s practically a dubstep track. Do you think that incorporating different genres into The Crystal Method’s sound is a good way to refresh things?

“There are only so many times when you can listen to the sound of a drill that’s being bored into the side of an oil tanker, and a lot of that dubstep sound is definitely for the youth, but I hear what you’re saying. A lot of that stuff has become passé, but there are definitely elements within that genre that can add something new if you can peel them out or frame them in a different way.

“On our self-titled The Crystal Method album back in 2014, the two of us got caught up in the middle of the whole rise of EDM and all that nonsense with bottles of tequila and vodka rolling around venues with firecrackers on top of them, so I’d love to go back in and rework that album someday.”

Another example of incorporating something new to your sound is the track Friction, which has nu-metal guitar riffs. Are those real or sampled?

“Jim Davies, who was in Pitchshifter and The Prodigy for many years, played guitars on that one, but the track is weird. It has real guitars but there’s also a great iPad additive synth called Cube that I had a lot of fun playing with because you can manipulate sounds on the fly and it has this really cool x, y, z crossover function.

“Friction is a crazy combination of live guitars, analogue synths and in-the-box and app synths – one of the guitars actually reminds me of an old John Lydon riff. That was another track that I couldn’t find the right vocal for, so we just kept it as is and decided to let people make their own interpretation.”

When you bought out the Crystalwerks studio from Ken, did you switch things up much?

“Although we used some hardware synths, most of our last self-titled album was made in the box and so I really wanted to change things up in the studio. Ken was more the engineer and I’d be at the back of the room grabbing and hooking up synths, so it was designed for two people.

“We had a D-Command Pro Tools setup, which was a paperweight really, so I moved the patch bay and got myself a Chandler mini mixer to route my synths through and bring everything a lot closer to me. I wasn’t happy with how the room sounded either so I got a Trinnov correction system to help me understand what the room was doing.”

How does the Trinnov Optimizer work exactly?

“The room was really well soundproofed but, because it’s so big and has high ceilings, I was having a lot of problems with bass traps and other frequencies – so much so I was thinking about selling the studio.

“I knew that Sonarworks made room correction software for DAWs connected through a master bus, but I was always sceptical of that technology because the concept of my computer calculating all the information it normally does, then doing it again right before it goes out, seemed like it might cause problems with delay.

“In the end, a friend of ours from Vintage King recommended the Trinnov, which comes with a really cool, specialised mic with four individual diodes that you set up in a sweet spot and then calculate a gamut of different sound frequencies through a totally separate unit that becomes your room correction and monitor source.”

How big a difference did that make for you?

“Considering the amount of years we’ve spent working here, when I saw the curve and how the standing waves were affecting the sound, it was remarkable. The room sounds awesome now, and although I still have to finesse the Trinnov and make certain adjustments, I love the idea of being able to pull it out of a little flight case with a pair of monitors and tune a room. It’s been a godsend and one of the best buys I’ve made over the past 15 years.”

What other production changes did you make?

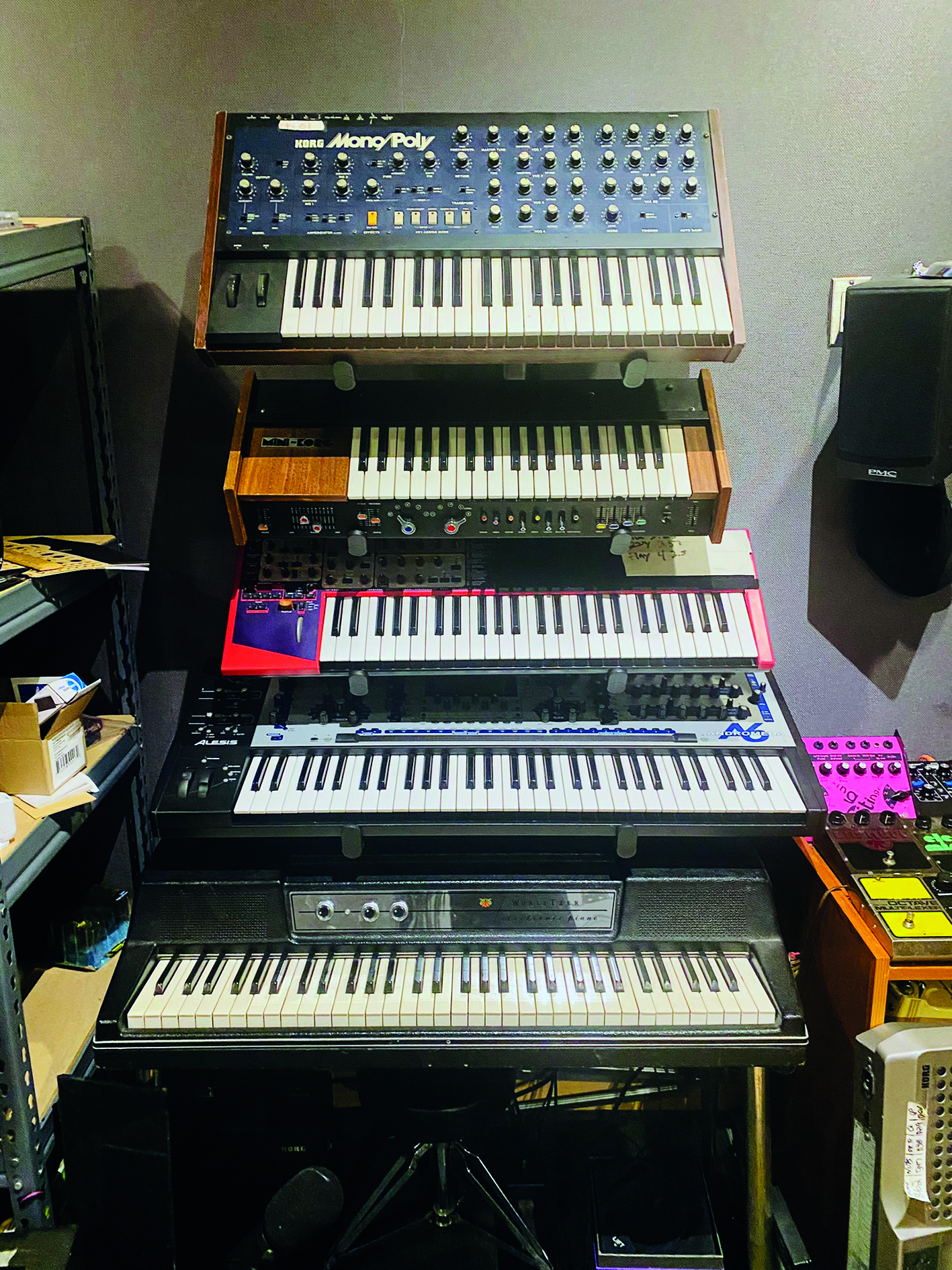

“I really wanted to get back to plugging in my old synths and analogue gear, even though they’re unpredictable and you always have issues with them. I have a Memorymoog and one of the oscillators is always drifting.

“I spent a lot of time getting it fixed but finally just accepted that when you move the faders around, it’s not always going to sound the same as before. That really put me more in the moment, because now when I start working with gear, I feel I have to immediately hit record.”

Is that more in tune with how you used to work?

“It’s definitely what we used to do back in the day. We didn’t have digital audio back then; we’d run a DAT while we were messing around with stuff, go to lunch, get back and find something cool on playback. When we were working with Tom Morello on the Tweekend album, he played the riff from the track Name of the Game while he was warming up.

“We asked him, ‘What was that!?’, but he couldn’t remember what he’d played. Lo and behold, he found it again and then we ended up working on his idea overnight, so I just really wanted to come back to that concept of plugging something in, adding a couple of pedals and hitting record.”

Do you have a specific outboard chain?

“Because I have so much gear going back to the early days mixed with modern stuff, I really use a whole hodgepodge of different methods because certain things just feel better going through certain outboard.

“I’ll typically run drums through my API 512c mic preamp, bass through the Shadow Hills amp and guitars through the Purple Audio Action 500 Series compressor, or I might use the Avalon VT-737 channel strip for vocals. When I’ve been working on things outside of the box or sending stuff through my Chandler mini rack mixer, I’ll mostly use the Rupert Neve Portico II master bus for processing.”

In Ken’s absence, have you been forced to learn more about the engineering side?

“I’m not the best engineer because I never took any classes. There’ve been many times when I’ve been working on something with my old Mackie mixer and not had a clue how to get it sounding right, so Ken would make sure he recorded it before I did my ‘engineering’ on it [laughs]. In the old days, we worked on Digital Performer, which I loved and would probably still be working on today if they’d made it more compatible when it came to automation.”

On the software side, the Acustica Audio Gainstation is touted to be a fairly unique device for sound mangling. Is that your experience?

“I’m always a sucker for some flash sale on plugins, or I’ll go down that rabbit hole of watching somebody work on something just to find a new trick that will make my process work in a different way. I find that software like Spiff and Soothe 2 are fantastic for carving out or accentuating sounds, especially when you’re using a lot of analogue distortion, but I’m always about finding the right sound first.

“I came to the Gainstation quite late – the producer VAAAL sold me on that, but my 2016 iMac didn’t like the software too much. He has a 2018 MacBook Pro but when I tried to open up one of his sessions it just said, ‘Nope, I’m not doing that’.”

Is there any sound tool that’s been a constant for you over the years?

“The Roland Jupiter-6 has been on every album. It’s one of my favourite synths and would definitely be a desert island choice because it just fits the sound of the band. It’s dirty, and can be pretty at times, but I love the cross filter frequency circuit.

“If you route a crazy limiter/compressor and plug a quarter-inch into the sustain pedal at the back then the whole synth becomes puffed up – like a puffer fish! I was worried that doing that would fuck up the synth somehow, but it makes a truly phenomenal sound. If you check out the track Watch Me Now you can hear this ridiculously distorted fat sound right at the end of it.”

The Crystal Method's new album The Trip Out is out April 15 via Ultra Music.

Future Music is the number one magazine for today's producers. Packed with technique and technology we'll help you make great new music. All-access artist interviews, in-depth gear reviews, essential production tutorials and much more. Every marvellous monthly edition features reliable reviews of the latest and greatest hardware and software technology and techniques, unparalleled advice, in-depth interviews, sensational free samples and so much more to improve the experience and outcome of your music-making.

“Excels at unique modulated timbres, atonal drones and microtonal sequences that reinvent themselves each time you dare to touch the synth”: Soma Laboratories Lyra-4 review

“A superb-sounding and well thought-out pro-end keyboard”: Roland V-Stage 88 & 76-note keyboards review