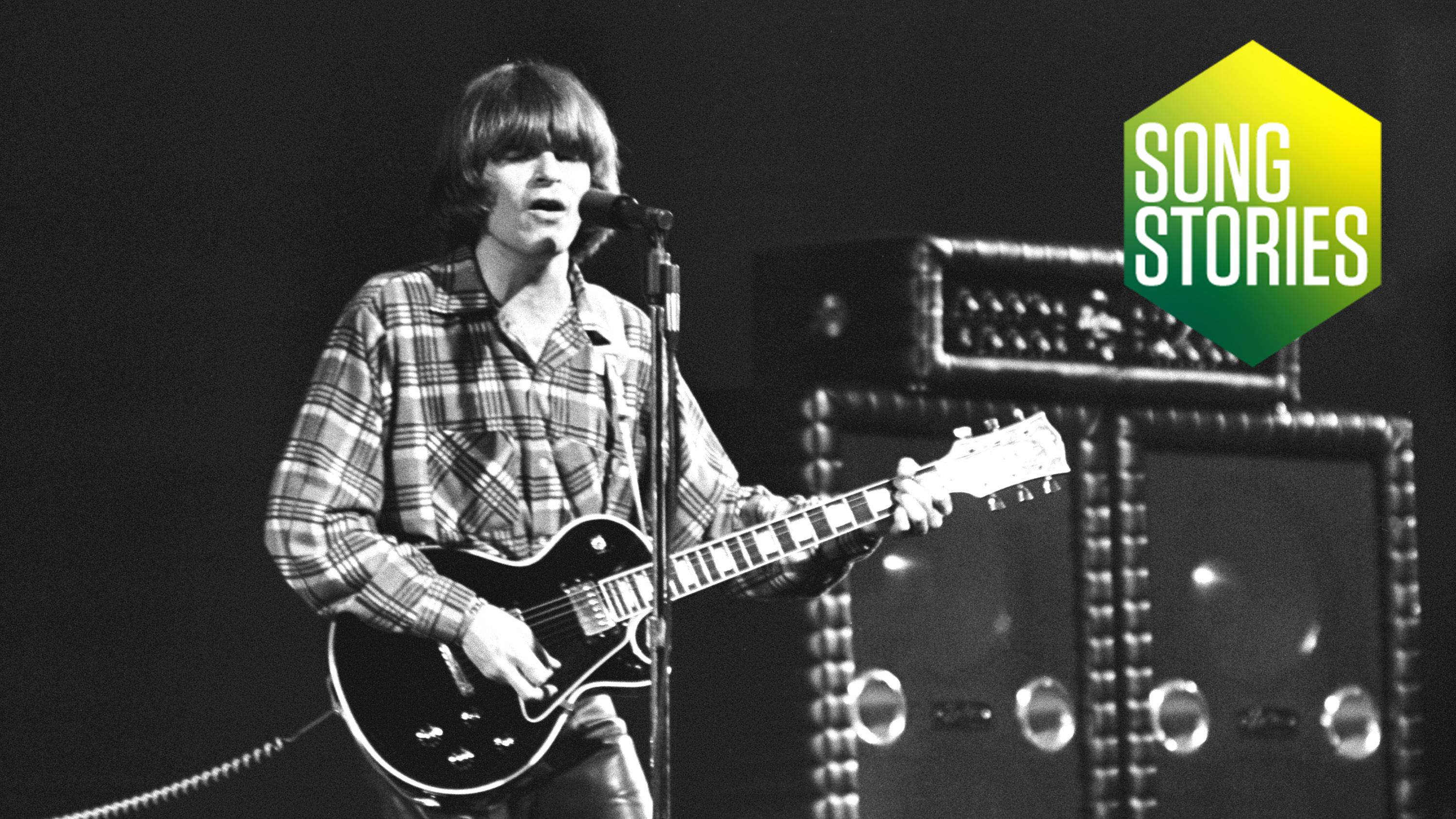

The story of Creedence Clearwater Revival's Bad Moon Rising: "A long time ago I adopted one of rock’s major tenets and stuck with it: be simple and speak powerfully”

For young disciplined bluesmen in plaid shirts and jeans, Creedence Clearwater Revival were nothing less than spectacular in 1969. Nobody seems to know it now but they were the biggest band in America by the dawn of the '70s – perhaps the finest pure rock ’n’ roll band the country has ever produced and one whose influence can be heard in bands from Nirvana to The Black Keys.

By the end of 1969, the four-piece of John Fogerty on vocals and guitar, his brother Tom Fogerty on guitar, Stu Cook on bass and drummer Doug Clifford had headlined the second night of Woodstock and their lynchpin songwriter and frontman Fogerty confirmed himself as a prolific hit-maker.

Creedence released no less than three stellar albums in the same year. Their run of glory would prove short before an ugly dissolution, but it was the smash hit from the second in the trilogy that would prove to be one of the cornerstones in their legacy.

All three of 1969’s Bayou Country, Green River and Willy And The Poor Boys are vital additions to the blues rock canon. Creedence’s sound was economic but they could boogie with the best – pop structure, blues strut and the sizzling essence of Americana. Fogerty called it “swamp music”: it meant and did serious business.

Creedence weren’t about image and hedonism; they sang of bayous, catfish, steamboats and ‘flattop rider’ railway stowaways. Their tales, rooted in the Southern heartlands of America, appealed to the young and old alike, raising their profile dramatically with a stunning run of singles. Not bad for a band from the San Francisco suburbs.

The infectious, horror-inspired Bad Moon Rising feels like a long way away from the blue skies above the Golden Gate Bridge. “I got the imagery from an old movie called The Devil And Daniel Webster,” Fogerty told Rolling Stone in 1993. “Basically, Daniel Webster makes a deal with Mr Scratch, the devil. It was supposed to be apocryphal.

"At one point in the movie, there was a huge hurricane. Everybody’s crops and houses are destroyed. Boom. Right next door is the guy’s field who made the deal with the devil, and his corn is still straight up, six feet. That image was in my mind. I went, ‘Holy mackerel!’”

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

It was about the apocalypse that was going to be visited upon us here

John Fogerty

But the actual meaning goes deeper, as John elaborated. “My song wasn’t about Mr Scratch, and it wasn’t about the deal. It was about the apocalypse that was going to be visited upon us. It wasn’t until the band was learning the song that I realised the dichotomy. You got this song with all these hurricanes and blowing and raging ruin and all that but it’s [snaps fingers] ‘I see a bad moon rising’. It’s a happy-sounding tune, right? It didn’t bother me at the time.”

To fuel its foreboding lyricism, musically Bad Moon Rising is classic Fogerty. A driving rhythm, less-is-more production and slapback vocal echo that nodded to the songwriter’s '50s heroes Elvis, Orbison and the Everlys. Indeed, the Green River album is a songsmith coming into his own. “Musically, Green River was everything that I was about,” Fogerty told Uncut in 2014. “I really enjoyed making it. I was really focused with the arrangements, the rehearsals, the necessities for each song.”

That’s what you’re hearing in the Bad Moon Rising riff – blues and country and me ripping off Scotty in my humble way

John Fogerty

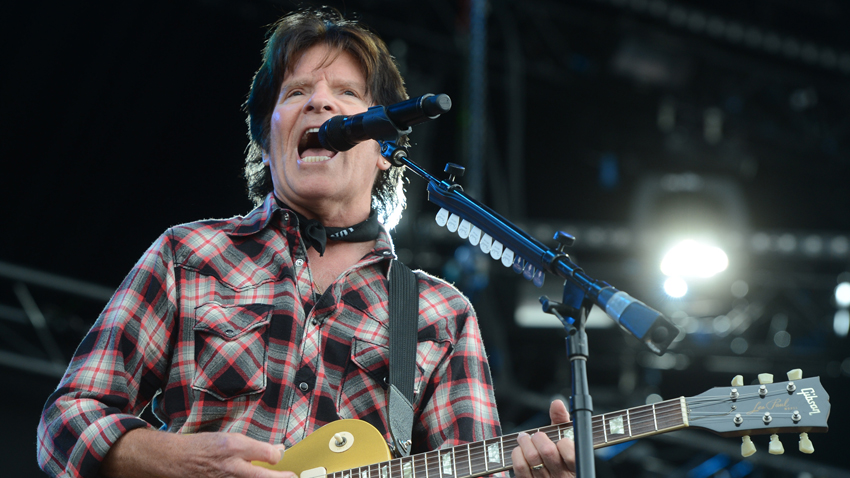

Gibson guitars became one of those essentials, often replacing Fogerty’s shorter scale Rickenbacker 325. For Green River’s predecessor, Bayou Country, an ES-175 had become his main squeeze for songs such as Bootleg and Proud Mary. But that guitar was stolen from his car and the replacement began a loyalty to Les Pauls that has continued ever since.

A Les Paul Custom became a staple for his DGCFAD-tuned and barre chorded swamp hits live. But the playing approach of Bad Moon Rising is harking back to Fogerty’s Sun Records heroes, namely Elvis’ guitarist Scotty Moore.

“Bad Moon Rising is a kind of a sideways You’re Left, You’re Right, She’s Gone from Elvis’ Sun Sessions,” he revealed to Guitar World in a 1998 interview. “Back then I couldn’t do the alternating bass thumb-pick stuff so I played it with a flat pick and used my fingers for the upper notes. It’s built around an open E chord with an added 6th, C#, and again I’m playing the G to G# in the riff.”

“Scotty is the man!” Fogerty continued, warming to his theme. “He was in the band that defined what the line-up of a rock ’n’ roll band would be, he was the lead guitar player melding blues and country and coming up with the bible of rock ’n’ roll. That’s what you’re hearing in the Bad Moon Rising riff – blues and country and me ripping off Scotty in my humble way.”

"I was quite a taskmaster with the band. But I was also hard on myself"

In the same interview, Fogerty went on to offer some valuable insight into his song’s economic but highly effective solo section, indicative of the Creedence touch. “It’s an example of little chords, triads, singing,” he explained. “The part is set up like a section of the song. The first phrase goes down and is answered by the second phrase, which goes up. Very simple. It’s sometimes hard to stay in that realm because I was like a first grader when

"I made up that part, but I often long for that simplicity – I think that way. That’s the deal, the promise of rock ’n’ roll, you might say. It’s the contract you make with your audience: to not become a noodler, to not lose them. A long time ago I adopted one of rock’s major tenets and stuck with it: be simple and speak powerfully.”

Perhaps nothing defines CCR’s musical legacy more than that. “In 1968 I always used to say that I wanted to make records they would still play on the radio in 10 years,” the songwriter told Rolling Stone. Over 50 years on, the charms of this song show no signs of fading.

Interview: John Fogerty talks guitar heroes and classic songs

Rob is the Reviews Editor for GuitarWorld.com and MusicRadar guitars, so spends most of his waking hours (and beyond) thinking about and trying the latest gear while making sure our reviews team is giving you thorough and honest tests of it. He's worked for guitar mags and sites as a writer and editor for nearly 20 years but still winces at the thought of restringing anything with a Floyd Rose.

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track

“Part of a beautiful American tradition”: A music theory expert explains the country roots of Beyoncé’s Texas Hold ‘Em, and why it also owes a debt to the blues