“I think that the whole band was kind of misunderstood by everybody, and it gave us a sort of an edge, you know": The story of Cream's Disraeli Gears

Best of 2024: How Baker, Bruce and Clapton transcended their (and their management's) very different ambitions for Cream to track a '60s masterpiece

Join us for our traditional look back at the news and features that floated your boat this year.

Best of 2024: Their volatile genius burned fast and bright, but after three albums and two years of non-stop touring, Cream were finally brought down by blinkered management and a gig schedule that would have felled an ox.

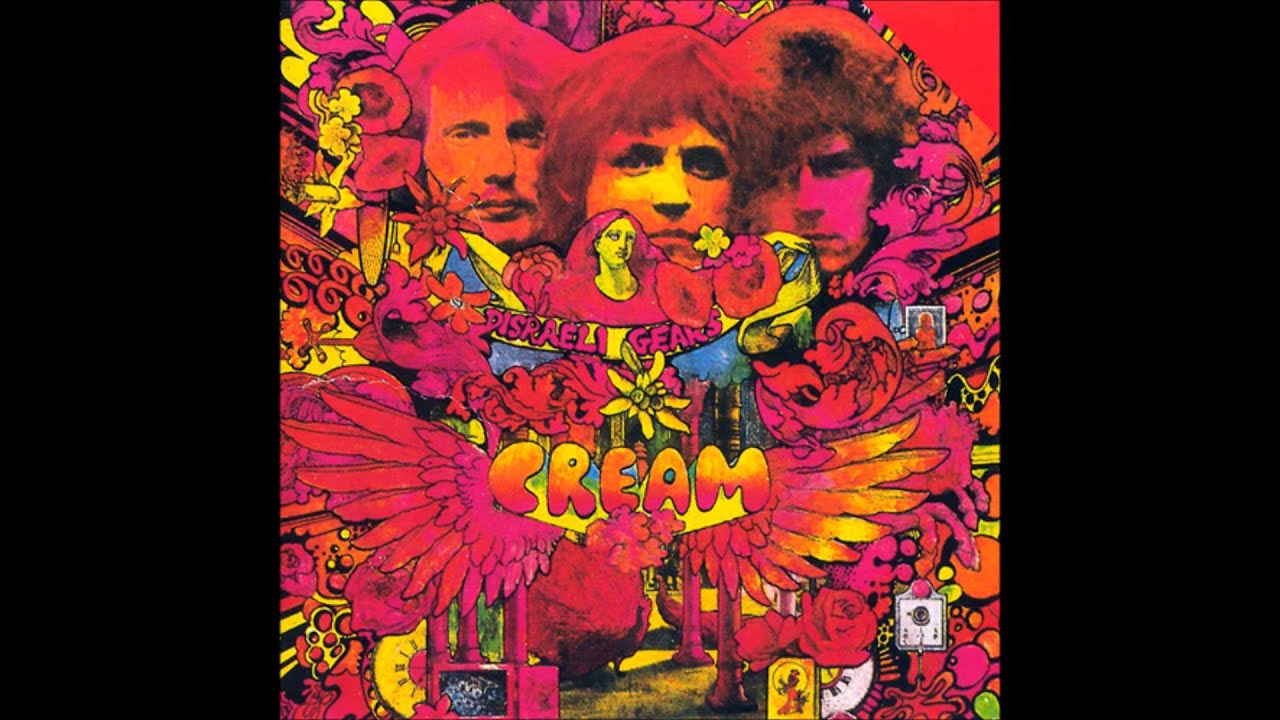

The apex of that short but brilliant career was the 1967 album Disraeli Gears. Epic in scope, it fused the blues and jazz together in a searing, psychedelic blast of 100-watt Marshall tone.

Jack Bruce sadly passed sadly passed away in 2014 but two years before his death he gave a detailed account of the album’s making to Guitarist magazine. Here we collect those exclusive insights from Jack and poet Pete Brown – who wrote classic tracks such as Sunshine Of Your Love together – about the making of the album.

Let’s get them out there and make them play every toilet in the US for as long as they’ll last before they go barmy or kill each other

Jack Bruce

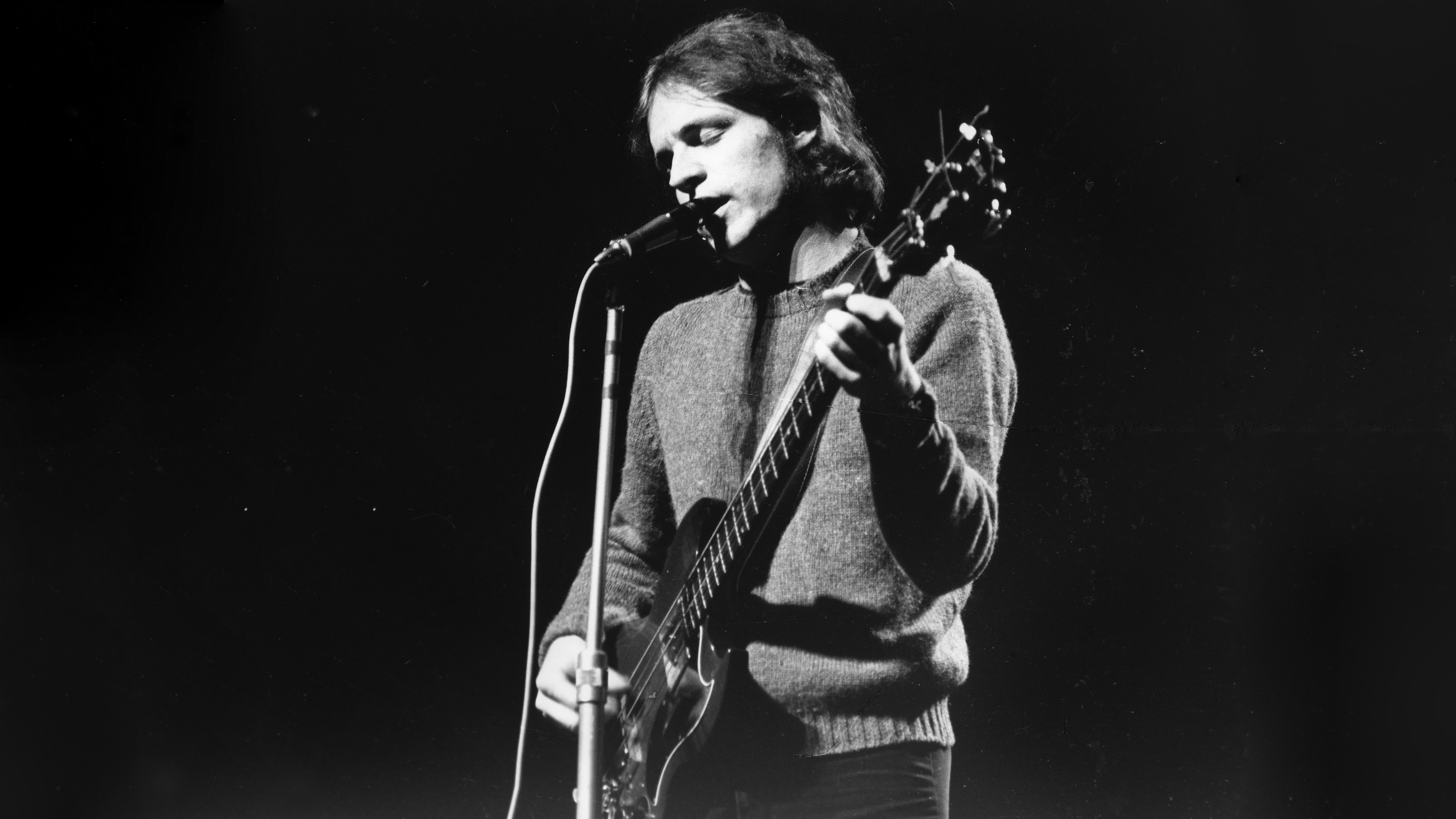

When Guitarist called up Jack Bruce to talk about Cream’s 1967 classic album Disraeli Gears, he leaves us in little doubt about the unique chemistry that fired an equally unique group. “I think that the whole band was kind of misunderstood by everybody, and it gave us a sort of an edge, you know,” the bass legend muses.

“I think Eric thought he was going to have this little blues trio and he would be sort of like Buddy Guy standing out the front. And then I thought: great, I can be a composer and get some songs out there. And I think Ginger just wanted to conquer the world, basically, like Genghis Khan or somebody. We had different ideas.

“Meanwhile, the management – the dire management of Robert Stigwood – was thinking, Let’s milk this for all it’s worth because it ain’t going to last. So let’s get them out there and make them play every toilet in the US for as long as they’ll last before they go barmy or kill each other…”

Listening to Bruce recalling the birth of Cream, you’d be forgiven for wondering how the greatest supergroup of the sixties – arguably of all time – lasted through the average week, let alone long enough to cut a masterpiece such as Disraeli Gears. Yet beneath Bruce’s wry recollections lies an intense and wholly justified pride in what the group achieved.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

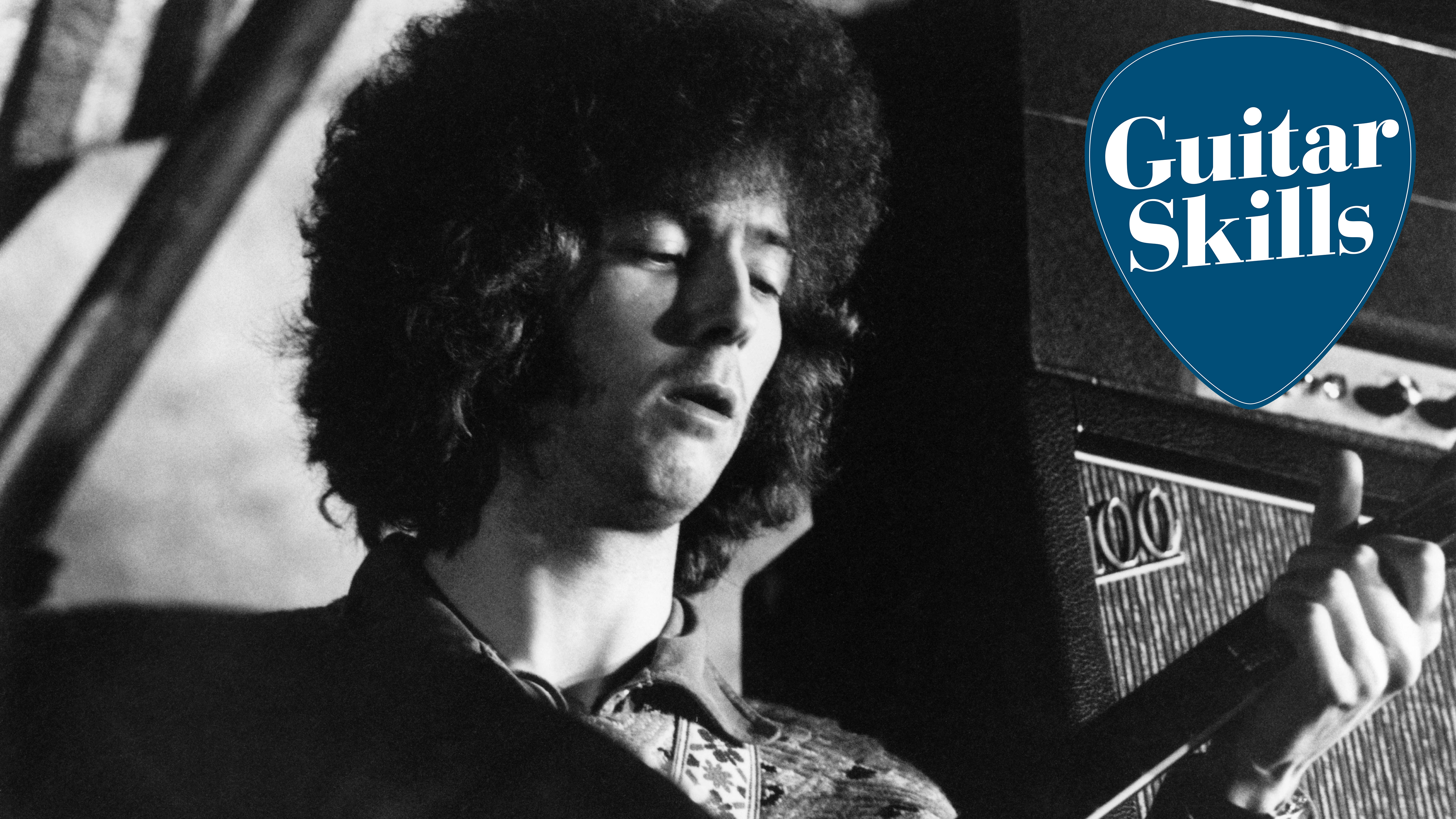

During Cream’s brief two-year lifespan, they had it all: in Eric Clapton a supremely talented guitarist whose only serious rival was Jimi Hendrix; in Jack Bruce a star bassist with the chops and vision of a jazz maestro; and in Ginger Baker a volatile but brilliant drummer capable of welding their contrasting talents together. Yet, initially, some doubted whether the band would produce anything more notable than a short-lived stream of cash.

They had absolutely no bloody idea. And when you look at it, it’s a miracle that it happened

Pete Brown

Pete Brown, the visionary London poet who co-wrote some of Cream’s greatest tracks, including Sunshine Of Your Love and White Room, was the fourth key figure in the story of Disraeli Gears. Today, he agrees that the degree to which the band shook up rock music shocked cynics.

“Cream’s management thought it was going to be an all-star band that would fill the blues clubs, and maybe be a nice festival attraction. They never thought it would spread; they never thought it would get to America; they never thought we’d have hit songs. They had absolutely no bloody idea. And when you look at it, it’s a miracle that it happened.”

Power trio

When I was young. I always thought I could really change the world through music

Jack Bruce

In the end, the mouthwatering prospect of what Jack Bruce could add to the band’s music overcame Baker’s objections. In March 1966 the trio met secretly for a first rehearsal at Ginger’s house in Neasden. As Clapton later noted, whatever tension existed between them “all just turned to magic” as soon as they started to play.

Jack Bruce was convinced that they had all the ingredients they needed to forge a new sound. “I did have grandiose conversations with Eric at the very beginning of the band, trying to come up with a kind of musical philosophy,” Bruce recalls.

“Eric was really into the blues and he knew a lot of stuff that I didn’t know. So I was being a bit presumptuous by saying, I love the blues, but I’d want to take it a step further and use the language of the blues as a way to write music for us.

“Eric understood, but he probably thought I was getting a lot on myself to say something like that,” Bruce reflects. “But I was always like that anyway, when I was young. I always thought I could really change the world through music.”

They didn’t say to Eric, 'You don’t know enough about chords, or, You don’t know enough about jazz to play with us.'

Pete Brown

Pete Brown argues that despite Clapton’s abundant talent and ferocious chops, working with jazz-trained players such as Bruce and Baker helped take his playing to another level.

“The one thing they never did, which I’m sure they got from [Alexis Korner band leader] Graham Bond, was that they didn’t put Eric down,” he adds. “They didn’t say, 'You don’t know enough about chords, or, You don’t know enough about jazz to play with us.' What they did say was: 'You’re a terrific player with terrific feeling, and if you play with us then this thing will happen – the magic will come.'” And it did.

Cream’s first album, Fresh Cream, was released in December 1966, reaching number six in the British charts and a single, I Feel Free, was picked up by ATCO – a subsidiary of US label Atlantic Records.

Ahmet Ertegun, the head of Atlantic, was influential and had Helped launch the careers of Ray Charles and Aretha Franklin. A way to break into America beckoned, although as Jack Bruce ruefully recalls: “It’s very important to remember that Cream were originally signed to Atlantic as a rider on the Bee Gees contract.”

Nine chaotic dates at the RKO Theater in New York followed in March 1967, plus one day at Atlantic Studios, where they recorded a Buddy Guy track, Hey Lawdy Mama, that would later evolve into Strange Brew. The next time Cream returned to New York, a month later, it would be to record Disraeli Gears.

Midnight express

“When I switched to electric bass guitar in the mid-1960s I didn’t know anything about bass guitars, really," admits Jack Bruce. "And at first I was kind of against them; I didn’t like them. But then I quickly fell in love with the ease of playability and all that stuff.

So I just went in and tried a few and I found this one that I liked, which turned out to be a Gibson EB3. I liked it because it was very compact and you could bend the strings.

“I thought, Well if you’re going to play a bass guitar, it should be like a guitar, not an upright bass. So at that time I thought it was really great to have this short-scale bass. I thought Fenders had this one sound that I didn’t want to go for.”

When the band returned to London, Jack Bruce and Pete Brown met up to write. With studio dates for Disraeli Gears just days away, the pressure was on to deliver new material. “They were milking us for every penny, so we never had any time to rest, or write, or live,” Jack Bruce explains.

“So Pete and me had to come up with some material for what was to be the next record. But we didn’t know what it was going to be. We were just desperately trying to find time to write songs, which usually entailed staying up all night in between gigs.”

Jack Bruce had already worked with Brown on earlier Cream hits, such as the single I Feel Free, for which Bruce scored out the song’s pop-rock melody on paper like a composer, while Brown provided the epic poetry of the lyrics.

“I don’t know why they needed me, because Jack and Ginger are both very, very intelligent people – and Eric too, though Eric wasn’t writing, hardly,” Brown reflects. “But then, I suppose I had a lot of chops as a writer by then. I as a well-known poet, and I wrote and practised a lot.” Bruce and Brown resumed their writing partnership as preparations for Disraeli Gears hit full swing, with songs written in the small hours and road-tested at gigs.

“Basically you’d come up with a song, then go into the studio and see if the guys liked it,” Jack Bruce recalls. “And if they did, it would go straight into the live act.”

Working on Sunshine

Learn the classic guitar riff from Sunshine Of Your Love by Cream

This high-intensity approach was how Cream’s most famous track, Sunshine Of Your Love, came about, Bruce explains.

“Pete and me were doing an all-night session at my place in Hampstead, at the flat, and we hadn’t really come up with anything,” he recalls. “And I picked up my double bass, which was lying there, and played the riff of Sunshine. Pete looked out the window and it was getting near dawn so he wrote, It’s getting near dawn. So there we had the first part, which is the part where the riff is, and we had the words of that. But we didn’t have a song. So we took it into rehearsal and Eric came up with the turnaround. Pete wrote the words for that and we had a song.”

“Later on our writing became more complex,” Pete Brown says. “But in that period of time it was a question of getting good alternatives: stuff that Jack felt happy singing. He had to feel good about the sounds of the words. “Sunshine Of Your Love really is a song about being on the road,” he adds, “coming home after you’ve done a gig and arguing with your girlfriend, who’s going to be in a receptive mood to have a nice little scene after you’ve been doing your hard work. It’s a gig song.”

It’s about sensuality, and the colours that come to mind when you’re having great sex

Pete Brown

Some may be surprised by how workmanlike the writing process was, with gigs and deadlines driving the creativity more than the band’s experiences. As Pete Brown explains, even the more tripped-out tracks on Disraeli Gears, such as She Walks Like A Bearded Rainbow, were not actually inspired by drugs.

“I remember this very psychedelic person saying to me when Disraeli Gears came out, Ah, that lyric, So many fantastic colours, on SWLABR. You must have been tripping when you wrote that,” and I said “No actually, it’s a completely sexual image to me. It’s about sensuality, and the colours that come to mind when you’re having great sex.”

Return to New York

The philosophy at Atlantic Studios was not, Let’s have this really great song or, Let’s have this riff,” Jack Bruce says. “It was, Let’s make a record

When May came around, the band were exhausted, but otherwise ready to cut the album. Although Bruce and Brown had done the lion’s share of the songwriting, Clapton had teamed up with Australian artist Martin Sharp to write Tales Of Brave Ulysses, which became a pillar of Cream’s live set. Sharp also designed the striking cover art for Disraeli Gears, highlighting what a melting-pot of sixties counterculture the album was.

When the band got to New York to record at Atlantic’s studio there, they were joined by two studio professionals who would further shape the sound of Disraeli Gears – producer Felix Pappalardi, who would later play bass in Mountain, and crack sound engineer Tom Dowd. With just one week of studio time in which to cut the album, their contributions would prove vital.

“The philosophy at Atlantic Studios was not, Let’s have this really great song or, Let’s have this riff,” Jack Bruce says. “It was, Let’s make a record. Tom Dowd was one of the all-time geniuses of recording and that’s what you had to do: you had to convince him that what you had was a proper record.”

Dowd and Pappalardi took the band’s gig-focused song arrangements and helped sculpt them into something that was more complex and satisfying for album listeners.

“When we played Sunshine Of Your Love live, before we went in the studio, it was much more of a straight-ahead rock feel,” Bruce recalls. “But Tom Dowd came up with an idea. He said, Why don’t you play it like in those Westerns where the Indians’ drums go: Boom boom boom. So Ginger tried that. Then it gave it a new life.”

Brewing up trouble

The move to Atlantic Studios saw Cream’s music evolve rapidly – it introduced record label politics. Bruce was dismayed to find that Clapton was viewed as the band leader by Atlantic executives, which influenced how another famous track from the album, Strange Brew, was recorded.

It still pisses me off because it sounds like the bass is playing the wrong tune throughout

“The way that came about was quite strange because we had already made a recording of a blues song called Hey Lawdy Mama,” Bruce recalls. “But then Felix Pappalardi was told there had been an executive decision that Eric had to front the band and I was going to be the bass-player guy who stood in the background quietly.

"So all of my material was sort of ‘non grata’, and they had to come up with a song for Eric to sing. So Felix took Lawdy Mama home and came back the next day with Strange Brew, which he had co-written with his wife, Gail. So that was how that came about. I was well pissed off, because the bass part that I had didn’t fit the new structure of this new song, although it was used.

"It still pisses me off because it sounds like the bass is playing the wrong tune throughout – which it wasn’t for the original thing. It was very much against my wishes, but I had absolutely no power in the band, in the studio – because Ahmet Ertegun was more or less in love with Eric. He thought Eric should be the frontman.”

The intervention by Atlantic executives was a reminder that, despite the obvious vision and talent of the band, Atlantic still had their eye on commercial hits driven by the fan-appeal of the band’s star guitarist. Nonetheless, when the week’s recording ended, it was clear to anyone with functioning ears that the band had cut a game-changing rock album.

Hitting top gear

When Disraeli Gears went on sale in late 1967, it was a hit in Britain – reaching number five in the charts – and an even bigger success in the States, where it went to number four. This prompted a punishing round of touring in America that signalled the beginning of the end for the band.

“It was enjoyable until they broke the band’s spirit by putting us on the one-nighters for seven months without anybody to help us,” Jack Bruce recalls. “That was what destroyed us – that and the lack of PA.”

The band cut two more albums at a breakneck pace in 1968 – Wheels Of Fire and their aptly named final recording, Goodbye. When Cream played their last British gigs at The Royal Albert Hall on 26 November everyone in the band was exhausted and ready to move on.

Disraeli Gears had undoubtedly been the highwater mark of the band’s astonishing two-year career. Looking back, what does Bruce feel about the album now? “I think you always would like another go,” he concludes, philosophically. “You’re never quite happy about it. There’s definitely things that could be changed and obviously you only hear the mistakes. But once it’s finished, it’s finished.”

Jamie Dickson is Editor-in-Chief of Guitarist magazine, Britain's best-selling and longest-running monthly for guitar players. He started his career at the Daily Telegraph in London, where his first assignment was interviewing blue-eyed soul legend Robert Palmer, going on to become a full-time author on music, writing for benchmark references such as 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die and Dorling Kindersley's How To Play Guitar Step By Step. He joined Guitarist in 2011 and since then it has been his privilege to interview everyone from B.B. King to St. Vincent for Guitarist's readers, while sharing insights into scores of historic guitars, from Rory Gallagher's '61 Strat to the first Martin D-28 ever made.