Country music legend Buddy Cannon: “When you’re having fun playing music, it makes its way to the listener”

The producer and songwriter talks collaborating with Kenny Chesney and Willie Nelson

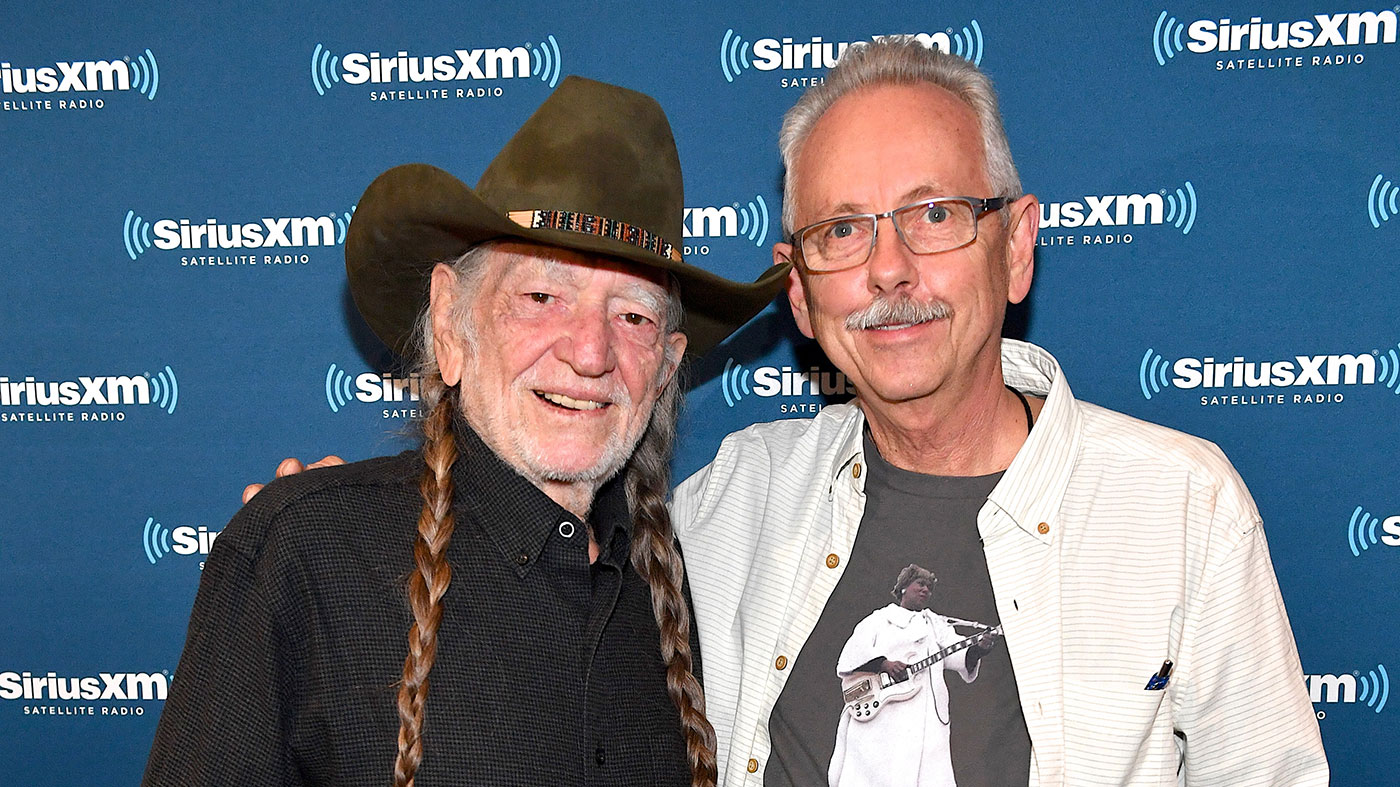

Buddy Cannon’s production skills have graced countless albums, among them almost an entire discography for Kenny Chesney over the course of two decades. Since 2007, Cannon has also collaborated with Willie Nelson, a relationship that began when Nelson added vocals to Chesney’s cover of Lucky Old Sun, the title track from his twelfth studio album.

Cannon grew up in a musical family in Lexington, Tennessee. He relocated to Nashville in the 1970s and landed a gig as bassist for Grand Ole Opry star Bob Luman. From there, he toured with Mel Tillis, a job that launched his songwriting career. He moved on to an A&R Director position at Mercury Records, where he signed and achieved success with Sammy Kershaw, beginning with the singer’s 1991 debut album, Don’t Go Near The Water.

In 1995, Cannon claimed his independence as a producer, which led him to Chesney, who had waited for the opportunity to forge a partnership. The two recently charted Chesney’s 30th No. 1 single, Get Along.

If I hire a guitar player, he’s already figured out what his sound is. I hire him for the way he sounds

An Academy of Country Music Producer of the Year, he has topped the charts for decades with albums and singles he produced, as well as with his original songs, which have been recorded by iconic artists such as Vern Gosdin, George Jones, and George Strait. He is currently in the studio with Alison Krauss, recording the follow-up to 2017’s Windy City, and will soon begin sessions with Reba McEntire for her upcoming album.

Cannon has an innate sense of what works when he’s behind the board. However, when it comes to the technical nuts and bolts, he defers to the expertise of engineers like Tony Castle, his right-hand man on dozens of projects.

“All I know is I can tell when it sounds the way I want it to,” he says candidly. “I wish I had a better answer for you, but the truth is that I totally rely on my engineers and musicians. If I hire a guitar player, he’s already figured out what his sound is. I hire him for the way he sounds, and between the guitar player and the engineer, if they can’t figure it out, me getting in there and acting like I know what I’m talking about ain’t going to change that a lot!”

Fun, fun, fun

I want to begin with a quote we heard during our recent interview with Mickey Raphael: “Buddy always puts together the best players. He’s a great songwriter and song finder... He lets the players play and will add suggestions when needed. He knows what he likes, and he’s not afraid to make a decision. He’s a fun guy in the studio, but he’s serious when he needs to be.” Would you say that’s accurate?

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“Yeah, I think so. I’m a very, very low-tech guy. That pretty well sums it up.”

Where did your ability to know a good song when you hear it, and to give direction as needed, come from?

I’ve always tried to get in the studio with great players that I love to hear play, and that are great people and like to laugh

“Well, I started out as a musician. I started playing in high school and always had music in my house. My mom played, my uncles played, and my first job when I moved to Nashville was as a bass player in a band. It was all about having fun when you’re playing music.

“I never had any aspirations of doing anything other than being in a band. I started writing songs out of boredom being on a tour bus. It was a pastime. It developed without me even realizing it. Mel Tillis heard a demo of some of those crude songs I’d been working on, and he ended up recording four of them at one time. A light bulb went off in my head and I thought, ‘Maybe I can do this.’

“Mel signed me to a publishing contract in 1976, and that’s where I began getting my taste of the studio life was doing demos. He hired me as a songwriter and as a song plugger and sort of a producer for all the demos in the publishing company, and the more that I did of that, the more I enjoyed it. I loved being around the musicians.

“Eventually, Mel sold his publishing company to PolyGram Records and I went to work for them. By then I was bitten really bad by the producing bug and was trying everything I could try to get my foot in the door there. Finally I managed to, and like Mickey said, I’ve always tried to get in the studio with great players that I love to hear play, and that are great people and like to laugh and have a good time. When you’re having fun playing music, it makes its way to the listener. So that’s always been my philosophy - to hire the best musicians you can find, who are in it for the music and the good time.”

Pro Tool pro

During that time you also worked for [powerhouse producer and head of several Nashville record labels] Jimmy Bowen. What was that like?

“My relationship with Bowen was at the exact time that Mel started recording my songs. Bowen had just moved to Nashville, and his first Nashville act that he produced was Mel Tillis. It happened to coincide with the same time that Mel discovered he liked my songs. The first songs I ever had recorded were Jimmy Bowen.

“I don’t know why he let me hang out in the studio with him. We never talked about it, but I really did spend a lot of time watching Bowen. He let me sing background vocals on something of Mel’s every now and then.

I don’t have to worry about Tony Castle recording something badly. I don’t have to tell him what to do

“I have nothing but respect and great admiration for Jimmy Bowen. He wasn’t the most popular guy to come to Nashville, because when he came here, he brought a different idea of how to record. Bowen had already seen the digital era rapidly approaching, and he ushered in the digital process of recording music in Nashville.

“Nashville was real clique-y, and Bowen started bringing in these guys like James Burton and Glen Dee Hardin and some other guys from Los Angeles to play on these records, and it really rubbed the Nashville A-Team guys wrong because they were being invaded. So he was not a popular guy here in town. But when somebody asks me about Bowen and tries to go negative, I tell them that the worst thing Bowen ever did to me was cut two Number One records on two of my songs. So I have nothing bad to say about Bowen.”

Tony Castle’s name has become almost synonymous with yours. You met when you were both working on a George Jones album. How has that relationship grown?

“Tony was an assistant engineer, and we were using an engineer by the name of Billy Sherrill. We were in a studio called Eleven Eleven that Larry Butler owned. Tony grew up on Pro Tools, and Billy was more of an old-school analog guy. Finally, Tony ended up being my chief engineer.

“When we first started working together, we were still working on the 32-track digital reel-to-reel machines, but that was only for a short time. I don’t have to worry about Tony recording something badly and having to fix stuff. I don’t have to tell him what to do. He knows what needs to be done to make me happy.”

Kenny Chesney and David Lee Murphy performing Dust On The Bottle before a crowd of zillions. From Chesney’s YouTube channel.

Chesney and Willie

Let’s look your working relationships with Kenny Chesney and Willie Nelson. How has your approach to producing them changed over the years?

“When I first started with Kenny, he was about three years into his life as a recording artist and he was still trying to figure out what he wanted to do. I was producing Sammy Kershaw, and Kenny loved the way those records sounded.

“I was working at Mercury Records in the A&R department, and Sammy was my first artist that I produced. Kenny was a songwriter for Acuff-Rose, and their office was across the street from Mercury. He used to come over and hang out in the lobby and flirt with the receptionist. That’s where I met Kenny, in that lobby at Mercury. I thought he was just a songwriter. I had no idea he had artist aspirations.

I saw something that Kenny had his eyes on something, and the best thing I knew to do was back out of his way, let him run

“One day he came in and asked me if he could talk to me for a minute, so we went in my office and he said, ‘I just got a record deal with Capricorn. I love what you do with Sammy Kershaw, and I want you and Norro [Wilson]’ - who I was working with - ‘to produce my record.’ Mercury had told me that I couldn’t do any outside production, so I had to turn Kenny down, and it killed me. I wanted so bad to get another act because we’d been real successful with Kershaw. So I had to tell him no. He went on and got Barry Beckett to do those first albums.

“I still wasn’t getting opportunities to do more production projects, so I quit the record company. As soon as Kenny found out, he had Renee Bell at BNA [where Chesney signed after his debut album] call me and say, ‘Do you want to produce him now?’ That’s how it started. At that time, I continued the basic style of production that we were doing with Kershaw. It’s who I was as a producer, and Kenny was still a fledgling artist. Our first single [She’s Got It All, from Chesney’s fourth album, I Will Stand, 1997], was a number one, and almost everything we did after that was Top Ten, maybe number 12, but then we started getting number ones with just about every record we did.

Willie Nelson and Kenny Chesney performing Poncho And Lefty at Merle Haggard tribute concert. Fan-shot video.

“Kenny started getting a vision, and as his vision got more in focus, he started becoming more hands-on in the music. It started evolving into this edgy kind of … more of a rock sound, and I saw something that I hadn’t been seeing before and had not been a part of as a producer, and that was Kenny had his eyes on something, and the best thing I knew to do was back out of his way, let him run, and be there if things started getting a little too weird.

“That’s how that grew. Then all of a sudden the island thing started creeping in. Kenny’s whole thing came from inside his brain, and I’ve been lucky enough to be a part of it. He trusts me to always tell him what I think, and it’s been a very interesting ride with him. He instinctively knows the right thing to do. It’s about doing something he hasn’t done before.

When Willie started singing, I looked up and Kenny was staring straight at me. It was a powerful moment

“Probably the biggest thing we have in common is a mutual respect for great songs. I never have to worry about him wanting to record an inferior song just because it has his name on it as a writer. He doesn’t do that. I don’t do that with songs that I write. I’ve been working with him for 22 years, and I’m a songwriter, but I’ve had maybe two songs of mine recorded on his projects, and I’m perfectly fine with that because they weren’t the right vehicle to get us to where we needed to go.

“My first project that I produced on Willie was a co-production with Kenny [Moment of Forever, 2008]. We both were huge fans of Willie’s and the opportunity was super-exciting for both of us. We had gotten to know Willie a little bit because we’d had him come in and lend his vocal on a couple of tracks on Kenny’s records over the years and we always had a good time.

“For the record that I co-produced with Kenny, we called in the same guys that we used on Kenny’s records, and they were just over the top at the opportunity to get to play with Willie. I remember the first time Willie sang a line in the microphone. We had set Kenny up in the room with the musicians, Willie was in a booth with his guitar, and I was in the control room.

“Kenny had a set of headphones on, he was sitting in the middle of the room where I could clearly see him, and when Willie started singing, I looked up and Kenny was staring straight at me. It was a powerful moment. I listened to that record again this past Sunday for the first time in two or three years, and it was so much fun, and there again I think you can hear that on the record.”

Willie Nelson performing Something You Get Through, from his latest album, Last Man Standing, released April 2018. Song written by Buddy Cannon.

Harnessing Trigger

What about recording his guitar? Willie Nelson has such an unmistakable sound.

“We do it different ways. Sometimes he’s present in the room when we record, and sometimes he’ll say, ‘Cut me a track on this song, and I’ll come in and sing and play guitar.’ It’s all different ways with Willie. His guitar, that old Martin, he plugs it into that amplifier, we have a mic on the front of the guitar, we mic the amp, and the amp is really the sound. Sometimes we don’t even use the mic on the guitar.

With Willie, it’s like he’s a jazz singer. He’s an improviser

“The whole identifiable thing is his guitar through that Baldwin Custom Professional amplifier. I have one just like it here in my office. I keep it here in case we need to fix something. He has a bunch of them. Every time somebody finds out there’s one around, they buy it. This one, an engineer in town called me two or three years ago and he said, ‘I’ve got this old amp like the one Willie plays. It’s never been used, and I’ve got to get rid of it. Would you mind asking Willie’s people if they want to buy this thing?’ I said, ‘How much do you want for it?’ He said, ‘Three hundred bucks.’ I said, ‘Hell no! I want it!’ So I bought it.”

You’ve said in the past that Willie doesn’t care if the music is loose, he doesn’t play the same thing twice, he does what feels right. How do you capture that?

“I think it’s that I’m so used to it. I started listening to Willie Nelson and understanding him the first time I ever heard him, which was back in the ’60s. I was always intrigued with his phrasing. It’s like he’s a jazz singer. He’s an improviser, totally an improviser. He knows he’s never going to do anything the same way twice, and he likes that. He never knows what he’s going to play when his fingers start moving. Every time he plays something, it’s like a new world, and that’s exciting to me. Willie wanders through the song, but it’s not like he’s just lost out there. He’s never lost.

“When I’m cutting a track for Willie, whether he’s there or not, we don’t move the track. We don’t cut to a click, because I think it’s more authentic with Willie to not be locked into a click, but the track is steady. The band is playing right on. It’s just a matter of putting the right band together. I handpick the guys I use on his records, guys who love to hear him play and sing, and it’s fun. We laugh our asses off when we’re working with Willie.”

With the band

How do you guide session players through someone else’s material?

“The first thing I like to do is, say I’m getting ready to cut a track on anybody. We won’t say Kenny, because he usually has an idea of where he wants the sound to go. Usually. But if I’m with Willie or another artist, I prefer to begin the session without a demo, with just a guitar/vocal or a piano/vocal most of the time.

I want to hear the band’s ideas before I start throwing mine in

“Unless there’s something specific that the songwriter has written into the song, like a lick or something, an identifiable thing, I prefer to start with just the piano/vocal or guitar/vocal and play it for the band. I want to hear their ideas before I start throwing mine in, because nine times out of ten, what they come up with is what we end up with, and it builds itself. We start with the song immediately, and within 45 minutes or an hour we’re finished with that song. It doesn’t always work like that, but usually.”

Can you become too comfortable in a longtime working relationship? Is it more difficult to challenge a musician you know so well?

“I don’t think we have that issue, because we have respect for each other. The big reason is that we try not to do the same song twice. It’s hard to find ten or twelve great songs. Kenny and I look for songs all the time, and when we do a record, we know we’ve got some interesting songs, and that washes away any boredom that could be there, but that isn’t there with us. Nothing lasts forever, but 22 years is a long time. Kenny was 27 years old when I started with him, and he just turned 50. Of course, I was a lot younger too!”

When was the last time you worked in analog?

“The last time I really cut analog was most likely when I was still doing publishing demos. When I got my first chance to make a record, the Sammy Kershaw record, we had already moved into 32-track digital reel-to-reel. That would have been 1990 or 1991, maybe. I have never produced an analog record. When I was doing publishing demos when I was working for Mel Tillis, I worked on analog every day. We had our own studio toward the end of my run with Mel, and I was in there every day working. I liked it, but the digital thing, I enjoyed that. It was a different sound. I kind of miss the old, warm sound of analog, but that was a different day.”

Let’s get physical

Are we all too precious about “the good old days”? Was it really that much fun to splice tape?

“We had one episode where we had to do that on digital tape because of a malfunction in the machine. It was on a Sammy Kershaw track we were doing for a Lynyrd Skynyrd tribute album [I Know a Little, Skynyrd Frynds, 1994]. The tension arm broke while they were rewinding a tape, and the digital tape flew everywhere and had crinkles in it.

“There was one guy in Nashville who had experience with splicing digital tape because of a similar situation. We had him come over and he managed to salvage it, but it was a touch-and-go time. We were mixing the record when that happened. It was very stressful.”

How does the industry look right now for producers and session musicians?

I keep hoping that somebody’s going to invent a new piece of hardware to play music on that requires a physical piece of product

“I wish there was a brighter picture that I could see as far as where people would be buying music again as opposed to streaming it. Unless you’re super-lucky, there’s not much money to be made out there as a producer. If you’re not doing it because you love music, you might as well get on a boat and sail off somewhere. With Kenny, we used to sell three, four, five million albums just about every time out. Now, if we happen to sell a million, it’s a huge thing.

“I don’t know what the future is. I keep hoping that somebody’s going to invent a new piece of hardware to play music on that requires a physical piece of product, something like the CD player, where you actually have to buy a physical thing that contains an album. I’m not so sure that won’t happen. I don’t know if it will remain all digital or streaming.

“I miss the days when you could pick up the record and see who played on it, who wrote the songs. I don’t know how to do that anymore unless you go and find a CD. My grandkids don’t know anything about CDs. That’s like a Model A Ford to them, something they heard about, maybe. Vinyl is sort of making a resurgence. It’s not huge, but at least there are some people who are buying vinyl albums. That’s promising, I think.”

Gear box

Tony Castle has been Buddy Cannon’s engineer since the mid-1990s. Together they’ve recorded Chesney, Nelson, Alison Krauss, Merle Haggard, George Jones, Jamey Johnson, and countless others. He also worked with Mickey Raphael and mixed the 2016 box set The Highwaymen Live - American Outlaws.

Castle provided us a quick look at the technical side of recording Kenny Chesney and Willie Nelson.

“If memory serves, Kenny Chesney and David Lee Murphy’s projects were both recorded at Blackbird Studio D,” he says.

“Electric guitar chains were an SM57 and Royer 121 on whatever cabinet the guitarist preferred, and a NEVE 1073 mic pre back to the console line-in of the API and bussed together to an 1176. I react to whatever the guitarist provides and how it fits the song, and tweak accordingly. On acoustic guitar, I used a Sony C800g through an API preamp to a GML 8200 EQ through a GML 8900 compressor. On Kenny’s album, it was also put through an amp mic’d with a 57 through the API console and blended in with the Sony.”

“Willie’s albums are often recorded at Sound Emporium A. Willie’s guitar, ‘Trigger,’ is run direct to a Baldwin amp. [We use] an SM57 through a NEVE 1073 through a Distressor, minimal compression. Willie’s vocal chain typically is a U47 through a 1073 and Tube Tech CL1b. Willie will often play and sing, so I record the vocal mic and the guitar mic and blend when we mix.”