Clouds: "I felt for a time that I had reached the limits of what I could do with Ableton, even though obviously there are so many more things possible"

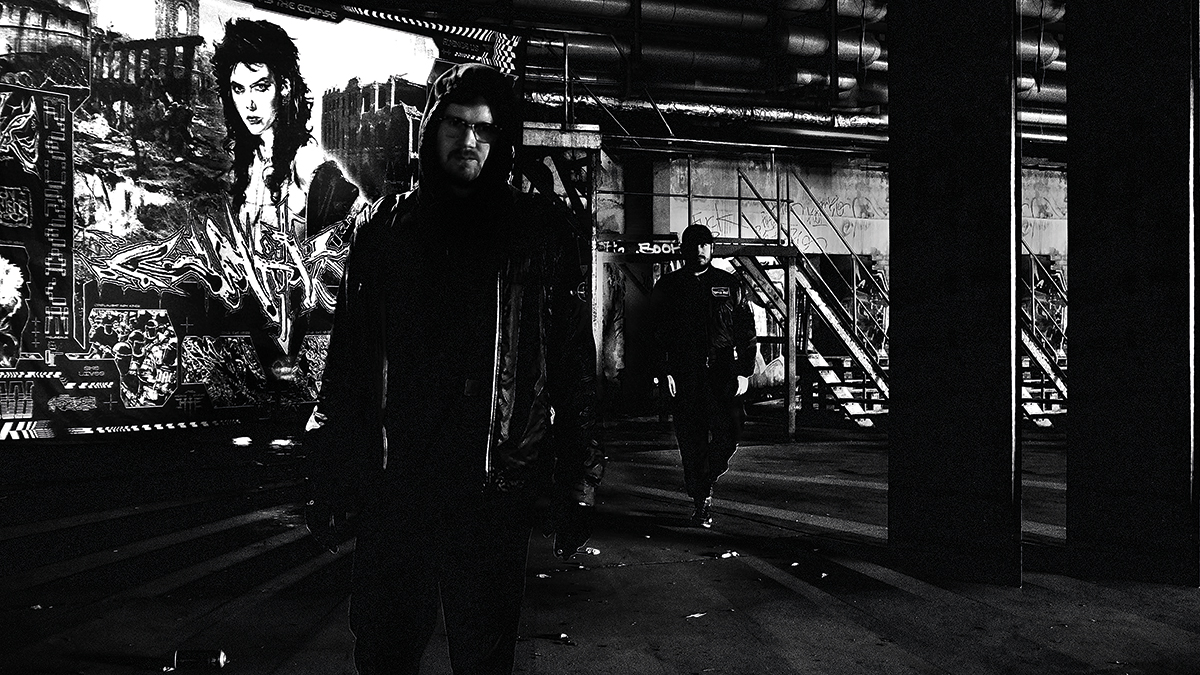

Scottish duo on grappling with the right hardware and software-based live setups

Scottish duo Liam Robertson and Calum Macleod may claim a preference for producing music in the box but, as we found out, it didn’t stop them creating a record whose scope is, literally, out of this world.

The setup for Scottish duo Clouds’ latest release is pretty high concept: “Neurealm, After The Fall – ruined and miserable; a drug-addicted populace trapped in torment, a military police with no order to protect or law to enforce which kills for sport, any rumoured escape route to the mountains guarded by crazed pagan zealots. There is only one form of anything resembling culture left: the enormous multi-day raves that take place inside the ruins of Parkzicht, the abandoned palace of art in the centre of the city.”

If you think this sounds like an ambitious start to a techno album, well, you’re probably right. There are only a handful of artists who’ve dared to use full-length albums to truly create idiosyncratic worlds, down to every last intricate hi-hat and reverberation. But Liam Robertson and Calum Macleod, known as Clouds, aren’t just any duo of techno misfits. Like fellow Scots Boards of Canada, Clouds seek to transport you to a totally new place, though it’s very unlike the sepia-toned purple-soaked hills of their brethren. Instead, it’s a fictional Glasgow 400 years in the future, when a mega-corp has taken over. “Welcome To Neurealm, After The Fall”, indeed.

Robertson and Macleod grew up together in Scotland and each lived in Glasgow for a few years, though neither calls the city home currently. Their clear artistic synergy makes sense when you know their history stretches back to pre-adolescent days.

Their latest album, Heavy The Eclipse, pairs 14 shape-shifting tracks of brutal mind melt with a full conceptual story, developed in tandem with acclaimed graphic designer David Rudnick, who helped extend the original ideas from a cast of characters into the full landscape called Neurealm.

The album was recorded over two weeks at Speedy J’s Rotterdam studio and released on his Electric Deluxe imprint, and sees Clouds make use of the veteran producer’s extensive hardware collection to first capture a range of sounds to be manipulated and arranged inside their preferred DAW, Ableton Live. We sat down with the duo to discuss this considered approach, what it was like to create this futuristic world, and their favourite sources for the perfect amount of grit.

So where did you guys meet?

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Liam: “We actually went to high school together, so we met when we were 12 or 13. We didn’t decide to work together as much as we just grew up together. ”

When did you start producing tunes?

Calum: “It was probably when we were around 14, we were getting into something, though I’m not really sure you’d call it production. It was part of a really small scene, primarily in Scotland, where people would just use Sony Acid Pro to throw a lot of acapellas over a hard dance track, and it was a really strange little scene. It was quite creative. You would try to make the samples say different lyrics, or use different acapellas. There were no releases of this stuff, it was just a matter of saving MP3s at 160kbps, sending it to a few people on MSN, and there was a forum as well, but that was kind of it.”

Liam: "Eventually it got bigger and people took it more seriously. We used to call it PC-DJing. One guy would do half of it, and then he’d send it to another guy, and they’d compete with who could make the most creative combinations of these acapellas. We weren’t doing it in the later years anymore, but it still goes on today to some extent.”

So eventually you moved on to Fruity Loops, and then to Ableton, correct?

Liam: “I had a brief stint on Logic, but yeah.”

Is it true you were a bit anti-hardware at first?

Liam: “I don’t know if it was that we were anti-hardware so much as it was a necessity. We were kids in school, so all we had was a laptop or family computer or whatever, unless your parents had synths around the house, which mine didn’t, Calum’s didn’t. We didn’t really get into hardware.”

Calum: “We made our first releases on the family computers. That didn’t go on for long; obviously we got our own machines but we’ve never really used hardware to make music. We did a live set for two years that was all hardware, no computer, but that was just something we wanted to do as an experiment, just to see what it would be like to take all these machines and jam for an hour in a club. Even though we had all these machines, this was in 2014 or 2015; we still didn’t really them use to make music. It was still all Ableton and samples.”

Liam: “I think it came from what you were used to, since we didn’t have those things growing up.”

Have you ever found a piece of hardware that you did find integral?

But most of the stuff, we didn’t know what we were doing, which was kind of good. Just turning it on and pressing all the wrong buttons and some really interesting sounds would come out.

Calum: “The only thing I can think of is the Mutable Instruments Clouds module. We used that a lot on our album. A lot of stuff is getting run through that. Even when we recorded the album, we spent a couple of days recording a lot of material and because we normally do stuff in the box and cut up samples, we just wanted source material. We weren’t using the gear to do live takes so much. There wasn’t a specific thing used on all the tracks; it was more just making sounds to choose from later.”

Liam: “We make our own sample pack, and then once we’ve got it, we’re in our realm and we can go into it. Speedy J had a mad amount of gear and an amazing studio to work in. There were all sorts of Junos and a bunch of other synths. All the key Roland players, from the ’80s up until now. Basically anything you want is on a shelf, and you can grab it.”

Calum: “We used a Nord rack quite a bit; we got a lot of sounds out of that. We used a lot of Juno and the Synthi EMS. We ran a lot of stuff through that as well. And the Korg Poly-800 was used on the last track, running through a bunch of modules. I had one of those in the past, so I knew what I was doing to some extent, but most of the stuff, we didn’t know what we were doing, which was kind of good. Just turning it on and pressing all the wrong buttons and some really interesting sounds would come out. Obviously Jochem (Speedy J) was there and he knew what he was doing more than we did, but we didn’t always go to him to help us set up things.”

How much of the process was he there for?

Calum: “He was there every day, but not all day long, every day. It was pretty laid back.”

Liam: “He has this project called STOOR where he brings in loads of artists to collaborate with him, and that was originally the plan of what we were going to do with him. But aside from a couple of tunes we primarily wanted to use the time in the studio to write an album, and he was very cool with that. So he knew he wasn’t going to have as much of a role as producer but was happy to help.”

Calum: “There’s still a lot of material where he was also on some synth or something while we were jamming, turning knobs. He also helped with the mixing right at the end because he knows the sound in the room really well. But when it came to writing the music in Ableton, he let us do that ourselves.”

Liam: “Once you have the source material and are doing the arranging, it’s sort of just a person and a mouse, clicking. It’s not something that three people can sit and be all involved in.”

So let’s talk about your live set for a second. How long did you perform it? I saw the photo on your Discogs page with an (Elektron) Analog Rytm; was that part of the live setup?

Liam: “I felt for a time that I had reached the limits of what I could do with Ableton, even though obviously there are so many more things possible, that I just didn’t know about. I wanted to do something a bit more hands-on and find things by accident. You have to be a lot better at engineering with sounds in the computer, whereas with hardware you just mess around with knobs.”

Calum: “We needed to do it to realise that we didn’t need (all that hardware). It was quite a good exercise. We had to see what we could do with these machines. We did it for a few years. Then, when I moved from Glasgow to Berlin, I left most of my stuff there with friends. It took us about four months to actually put the live set together. It wasn’t really a set that we’d written up; it was more just us jamming for an hour.”

Liam: “It was all improvised.”

Calum: “And the pieces of gear we were using kept evolving every time we played. We started with a Tempest, and then we sold that and got an Analog Rytm. The modules in my modular were always changing as well. We would always be searching for sounds that had a certain attitude or atmosphere, and then once we found that, we would just start jamming. We did that for about two years, though it wasn’t every show. We still DJed a lot as well.”

Liam: “But it was a bit scary as well, because it was obviously all of our studio equipment, and it’s a lot of money, and sometimes we’d lose a bag or it would get thrown around.”

Calum: “We realised it wasn’t like doing a ‘Clouds’ performance. It didn’t sound like Clouds to me.”

Liam: “All the tunes we’d made before then were made in Ableton and suddenly people were hearing something different than I think they were familiar with, which I think wasn’t a good thing.”

So what did your live set evolve into after you decided to ditch all the hardware?

Calum: “We don’t actually have one right now, though we’re about to start building one. We’ve just been DJing since then, but when we DJ we only play our own music.”

Liam: “So we’ve been making tunes just to DJ with, and it almost feels like making a live set because you’re building snippets to go with other tracks you have, and making weird little tidbits of music.”

Calum: “A lot of things are not really DJ-friendly for other people to play because we’re arranging things based purely for our own sets. A lot of the tracks aren’t very loop-y, because we use CDJs.”

How long have you been DJing with just your own music? It’s sort of a novel idea these days, even though it wasn’t in the beginning given how important exclusivity was.

Liam: “It’s been since about 2016. When we started out we weren’t confident enough in our tunes to play them out, so most stuff we played was other people. We were producers first and DJs second, so it wasn’t really in our nature to go crate digging and that sort of thing. I’d much rather be spending my time making something.”

Calum: “I’m still hesitant to call myself a DJ because I’m not really into the idea of going into a club and just showing my tastes, like, ‘here’s the kind of music I like, listen to it for two hours’. I was always trying to find that one track that’s the perfect track to play, you know? We were playing stuff I wasn’t really happy with. Every week I needed something new to play and eventually we just started making those tracks, because no one can make what we want to play better than we can. So I just started to make it.”

So, the album has a heavy conceptual slant. How much is it influenced by today’s politics?

All sorts of cultural references are relevant – we’ve both been playing the Dark Souls video game a lot leading up to the record, so that had a big influence, at least subconsciously.”

Liam: “Well, we went to write the album and we didn’t think, well let’s write a conceptual album about Glasgow 400 years in the future. I think Calum and I are just on the same page with what we want to do, there’s a symbiosis when we go into the studio and start writing stuff. After those two weeks, we started naming the tracks and getting words down that expressed some of the ideas that we thought we had captured, and how we thought the album sounded. So it really started with the tracklist. Then we got in touch with our friend David (Rudnick), who did all the graphics for it, and then spent the next two years building that concept from the initial idea. We basically developed these three crews and the Hunter character and from that, these ideas came about a barren wasteland. David had the idea of creating the Railnet for it and I think the idea of a future Glasgow came together really naturally.

“It’s basically a response to all of these things non-stop as you’re living your life, the world’s political situation is always on your mind and in the media so you can’t write a record and put that to the side. All sorts of cultural references are relevant – we’ve both been playing the Dark Souls video game a lot leading up to the record, so that had a big influence, at least subconsciously.”

The record has a lot of incredible distorted textures that range from really crunchy to really low bit-rate. What tools in the box do you rely on? Any go-to sources for saturation/distortion?

Calum: “Recently I’ve been using a lot of granular stuff and resampling, and a few little plugins for Max for Live. One of them is just something that squares waveforms really nice, just like a very nice simple distortion. Other than that we use a lot of Ableton’s own plugins, like the overdrive quite a bit. We used Ozone a bit more on the ‘engineering’ side, sometimes on the master but also on individual tracks as well, just to get an effect.”

Being as reliant as you both are on samples, do you have any go-to VST instruments?

Calum: “I recently got Sylenth1, which I like quite a bit. I think Liam got it as well. We’ve been doing these experiments where we try to make a full track just using Sylenth1 – using it for the kick drums and everything. It’s cool because you get a really coherent sound and mix and it just sounds right, so that’s been fun. I know a lot of people who rely really heavily on a sample pack or one particular VST, or they use one kick all the time, over and over. They spend days making a kick sound. If you can pick the right source material, and just use it in an interesting way, you can inject your own vibe into it.

“In general though, we don’t pay that much attention to gear, VSTs, or technique. It’s mostly using whatever we can to find the right atmosphere, and obviously that doesn’t really come quickly. I guess it comes down to choosing the right samples and putting them in the right place.”

Heavy The Eclipse is out now on Electric Deluxe.