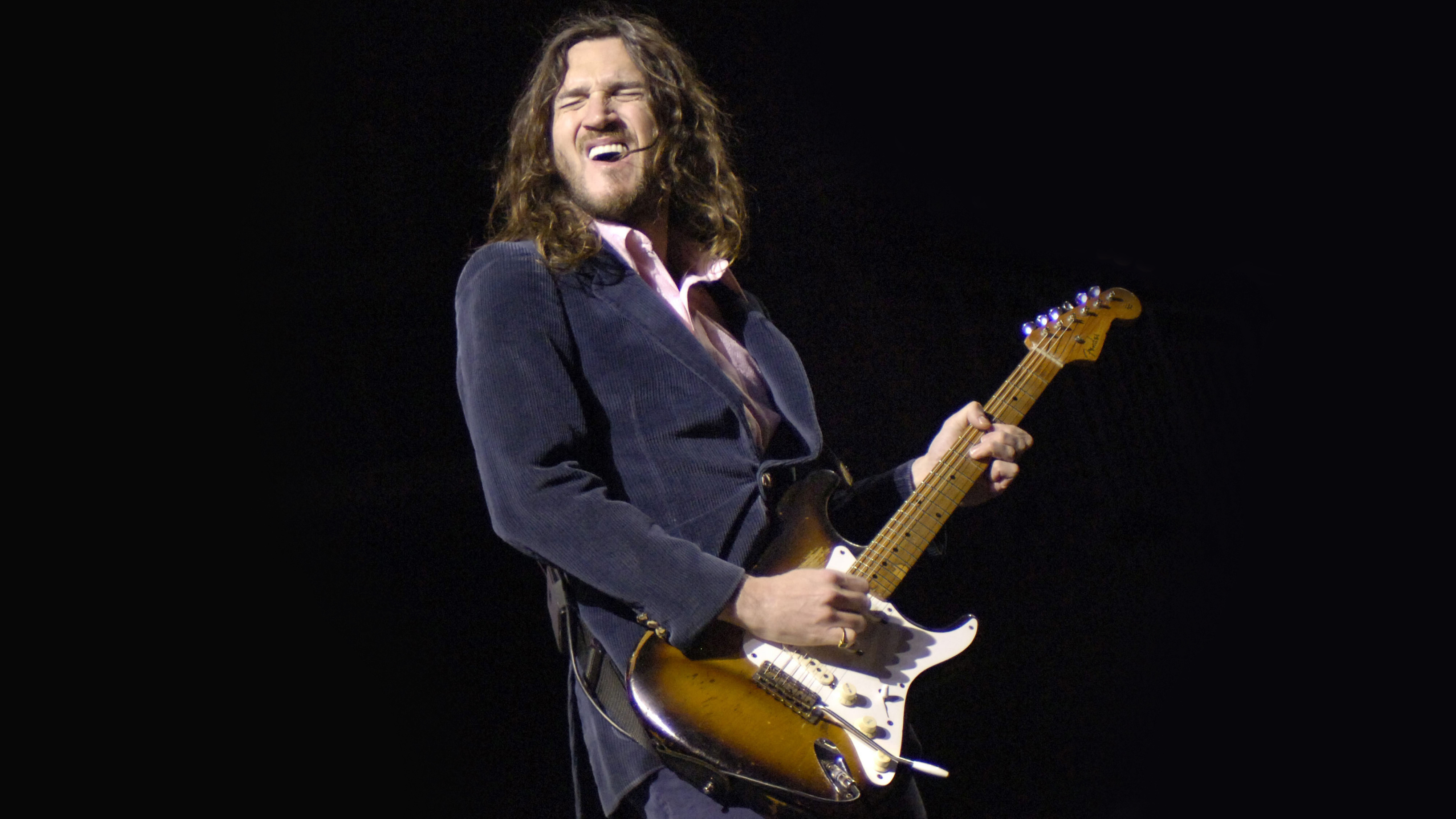

Classic interview: John Frusciante – "The only album I remember feeling totally and completely confident on 100 per cent was By The Way, and I wasn’t actually challenging myself on that album"

A huge in-depth conversation with the Red Hot Chili Peppers man from 2006 covering Stadium Arcadium, improvisation, meditation, Hendrix and much, much more

In 2006 Total Guitar met with John Frusciante in London to talk about the Red Hot Chili Peppers' 28-song double opus Stadium Arcadium and much more. The resulting interview was so big it ran over two consecutive issues. Here, we present the whole conversation online…

Stadium Arcadium was recorded at the same studio where you recorded 1991’s Blood Sugar Sex Magic album. What was the reasoning behind that?

“It just seemed like the perfect idea because I live about one minute away and Anthony and Chad live about 10 minutes away. Flea’s about an hour away in Malaga, but because of the way it’s set up he could sleep at the studio.

Flea made it his home for the week and then went home for the weekends. So it was just practical in that way. Also, the studio we normally use, Cello Studios [where we did Californication and By The Way], closed down.”

"Blood Sugar was naked. At the time that was the concept I wanted"

Did recording in the house bring back any memories?

“Not really. It seems like a different place now to what it was then. I like it better now. It’s cosier, a little more warm and homely. The other guys have a different impression than me, but that’s how it seemed to me. I loved it both times but before it seemed more cold and chilling.”

How different was the recording process to when you recorded all those years ago?

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“Well, back then I didn’t do many overdubs. Blood Sugar was naked. At the time that was the concept I wanted, especially because on Mother’s Milk [producer] Michael Bienhorn had really pushed us. He’d had me quadrupling guitars, so it was years before I ever doubled anything again because I had such a weird experience on Mother’s Milk.

"I did a lot of doubling on this album and it came out really good, but I hadn’t done doubling since Mother’s Milk. The template for Stadium Arcadium was to have an album like Black Sabbath’s Master Of Reality where the guitars are in stereo, hard left, hard right, and it’s just the simple powerchord and sounds as thick as you’d ever want it to sound.”

By the time we recorded Blood Sugar, I still felt as though I was doing a balancing act and I didn’t really feel comfortable with what I was doing

Do you ever look back to the Funky Monks film that was made at the time of Blood Sugar? How do you feel about watching yourself back then?

“I have all the respect in the world for my guitar playing then, especially as that was a point when I’d broken out of being in a particular place. When I was a teenager I loved Jimi Hendrix, Frank Zappa and Steve Vai, and I was balancing out those three guitarists styles in my playing. I didn’t have my own identity and I didn’t know what my musical voice was going to be.

"Around the time we started writing Blood Sugar, I finally put aside those guitarists styles and I forgot about what’s technically good. I thought, for example, that Keith Richards makes music that connects with so many people and he plays in such a simple way, so why don’t I pick a variety of people along those lines who play simply but do something that makes a beautiful sound that affects people emotionally? For me that was a new way of thinking that took a little adjusting to.

"So by the time we recorded Blood Sugar, I still felt as though I was doing a balancing act and I didn’t really feel comfortable with what I was doing, which is probably a good thing. The same thing happened when we were making this record. I felt as though it could just as easily be bad as it could be good.“

In what way weren’t you comfortable recording Stadium Arcadium?

“I felt like I was skating on thin ice or walking on a tight rope. It seems that a lot of the time things that are good have that quality about them. The only album I remember feeling totally and completely confident on 100 per cent was By The Way, and I wasn’t actually challenging myself on that album. I knew exactly what I was going to do in the studio, so it’s easy to feel powerful and confident when you have over-practised and you’re playing below your level of technique.

"On Blood Sugar I was being very careful to not think and to play from somewhere else other than using my brain activity to play the guitar. I would shut off my brain and let my fingers just go and listen to the rest of the music; listen to the bass and the drums, and not really listen to myself except maybe the sound coming back from my own guitar.

"if you shut off your brain you will notice that music exists beyond anything that we perceive with our five senses"

“I started it with the keen feeling that there were beings of higher intelligence controlling what I was doing, and I didn’t know how to talk about it or explain it. I called them ‘spirits’. It was very clear to me that the music was coming from somewhere other than me. But if you shut off your brain you will notice that music exists beyond anything that we perceive with our five senses, and we don’t really understand how it is that music exists in the air and comes through us as a vehicle. But it does. And on this album, meditation for six months prior to us going into the studio had a big effect on my ability to be able to turn off my mind. That’s where a lot of the music came from.”

Many guitarists will be interested in this facet of your work. Please explain how meditation helped your playing and how you’ve developed it?

“There are different kinds of meditation. There is one kind where the mind focuses on one object that could be a blue circle or a person’s face that you like, or a mantra. The concept is that your brain has been able to do exactly what it wants your whole life, thinking whatever it wants to think and that it’s basically this organ in your body that’s run amock. Your brain is interfering with your ability to be in the moment and the idea is to cause the brain to focus on one particular thing for an extended period of time.

“Then there’s another type of meditation where you’re bringing awareness to your brain. We say bringing awareness because it’s not the same as paying attention. You’re letting your brain go through whatever it needs to go through to process, but there are games you play with yourself. It’s a little bit beyond the scope of this to explain them in detail, but basically your brain gets sick of these games that you make it go through and eventually you get to sit there in silence and just bring that awareness to the silence.

"I hear music so much sharper now, and when I hear a solo I learn it so much quicker"

“In both of those ways it is an incredibly powerful feeling when you can just sit there and focus on the mantra, stillness or silence. When you do this for a half hour, one hour or two hours a day, what I’ve noticed for myself and for every other musician who has done this for an extensive amount of time – John McLaughlin, Robert Fripp and people like that – is that it brings this energy and focus to your musical practice and to your listening to music.

The only thing I can compare it to is when I first started smoking pot, where music had much fuller body than it had ever had before. I hear music so much sharper now, and when I hear a solo I learn it so much quicker. When ideas are flowing my drive to let the idea come to its complete fruition is relentless.

The idea being that if you can focus on nothingness for a half hour or an hour, it’s no problem to focus on something that gives you pleasure, like music.”

So how does meditation affect your ability to learn solos?

“Have you ever learned a solo, then a year later you realise that you had figured it out wrong? You didn’t hear a little bit, and when you think back to that time there was some little tiny voice in your head that told you it wasn’t exactly right but you didn’t have any real contact with that side of your brain so you didn’t listen to it.

“Well, once you start meditating you can’t bullshit yourself like that. Once you start meditating and you’re doing it for the right reasons, you have to be honest with yourself all the time and you have to be honest with other people. It forces you to clear through your shit. It compartmentalises things in your brain so when you set out to do a task, like learning a solo or a piece of music, your brain is 100 per cent with you and unified to that one task.”

"When I was a kid I would figure out Jimi Hendrix solos but I was learning a skeleton, or I would learn it and there would be some little detail that I wasn’t picking up"

Do you still learn other artist’s material on a regular basis?

“Oh yeah, all the time. At the moment I’m excited about understanding how classical composers thought – people like Brahms and Beethoven, Bach and Mozart. I’ll basically take a piece of their music and dissect it. Maybe just a couple of minutes at a time, a section that really speaks to me where I feel, ‘Wow, what is going on there? That is so beautiful, how are they creating those feelings? What is this change that’s happening right at this second and why does this part in the song make me feel so emotional for these two seconds?’ And then I’ll learn every part whether it’s an orchestra, string quartet or whatever.

“Or I’ll learn a Jimi Hendrix solo in great detail. Big solos for me when we were making this record were the long version of Voodoo Child: the three long solos from that track. When I was a kid I would figure out Jimi Hendrix solos but I was learning a skeleton, or I would learn it and there would be some little detail that I wasn’t picking up.

"In the first few months that I was meditating, I made the most progress I’d ever made. I felt like, ‘Jesus Christ! I’m learning exactly what he’s doing,’ and not only learning it but I’m learning to feel it the way he was feeling it and I’m learning to hit the string in the same way and to put the same vibrato on it.

"It’s not enough just to make a mental observation of what kind of vibrato you think he was using, you’ve got to feel it the way he was feeling it. That didn’t happen to me until I started meditating.

"Pretty much everything on Electric Ladyland was my bible when we were making this record because, not only is his guitar playing always speeding up and slowing down, he was playing around with lots of rhythmic expression and off-time playing, which was what I wanted to do with this album. The production and sense of constant movement and motion on [Electric Ladyland] that Hendrix caused as a producer was what I wanted to have my own version of.”

"A lot of musicians play within a 16th note grid: any note that they play is going to land on any one of those 16th notes. That was the last thing I wanted to do"

Was that aspect of Hendrix’s work difficult to replicate? How did you go about it?

“In his case he’s playing with the pan pots a lot, putting tape phasing on a lot of things, turning the volume up and down while he’s soloing. Basically playing with the mixing part of the process. I actually did my work before that.

After I recorded the guitars I’d effect them with my [Doepfer A100] modular synthesizer and Moogerfooger pedals. It’s that same idea of altering the sound after you’ve played it and not letting anything be static so that the sound is in a constant state of change. That idea was very important to me.”

Can you tell us more about the appeal of the Doepfer A100?

"The main reason you would want to use one is because if you buy a filter effect, a flanger or a phase shifter, in a sense the knobs are being turned for you. There are a lot of decisions being made for you by the maker. A modular synthesizer may look like a big crazy thing, but it’s basically a bunch of different filters and a load of ways in which to control those filters: by using your hands with the LFO [Low Frequency Oscillator], which makes the filter open and close at a certain consistent rate, and with an ADSR or an envelope generator, which [when you hit a string] makes the attack of the note open in a certain way; hold it there in a certain way, drop in a certain way and shut out in a certain way.

"Attack, decay, sustain and release: the four qualities of any sound. If you’re changing the sound of your guitar after it’s recorded, you have the option of being able to move the knobs yourself. For example, in sections of Dani California you will hear that all of a sudden the same guitar spreads out in stereo and there’s the clean one on the left and the treated one on the right. I’ve got the envelope generator controlling the filter as well as my fingers controlling the filter, so I can really bring out the subtleties of each note.

"If people don’t know what a filter is, it’s something that takes a sound from the whole spectrum of frequencies that it could possibly exist in. There’s hi-pass filters that can bring a note from nothingness to the tiniest little sliver of a frequency and open it up into being the full note, and lo-pass fi lters that take it from the point of being closed up, like a mouth with a hand over it, and open it up.

“This is basically what a wah pedal does, but the synth has a much wider range. It took me about six months to understand the thing and I regret to say that when I’m talking about it I’m sure it sounds confusing! But, to put it simply, the modular synthesizer is a giant effect. It’s a way of being able to play with the sound of what you do and be able to control the sound as a sonic event and not just as a guy playing guitar.

“On the C’Mon Girl solo, for example, I’m treating the reverb of the guitar with a hi-pass filter and I’m doing it with the tape flipped over backwards. I did it on two recording tracks. It sounds like stars shooting through the sky – I don’t really know how to describe it – but that’s nothing you would ever hear coming out of an effects box. The modular synthesiser is on the expensive side, but I think for the equivalent of about £500 or £600 you could get a basic system and expand it if you want to.

Modules themselves are expensive, and you need a certain amount of modules to be able to do anything – you’d probably need 12 or 13 modules to get started – so maybe it is a rich man’s game. But it’s no more expensive than a nice guitar!”

You’re soloing more on this record. Was that a conscious decision?

“I’m a person who likes to contradict himself and go against what he was doing before, and on By The Way I was completely against soloing. I didn’t enjoy listening to solos and I didn’t enjoy soloing. My perception of guitar playing at the time was influenced by John McGeoch from Siouxsie And the Banshees and Magazine, Johnny Marr of The Smiths and Bernard Sumner of New Order and Joy Division. If I was going to play lead guitar I wanted it to be something you could sing. But, as one would expect, I got sick of that at a certain point and by the time we were going to start writing this record I was really into soloing.

"I started getting particularly excited about anybody who was doing off-time stuff. A lot of musicians play within a 16th note grid: any note that they play is going to land on any one of those 16th notes. That was the last thing I wanted to do.

"At first it wasn’t so much that I was listening to Jimi Hendrix or Cream, I was listening to singers like Beyoncé, Alliyah and Brandy, and rappers like Wu-Tang, Eminem and Eric B and Rakim. I would translate the rhythmic phrasing and bluesy kind of things that they do to the guitar and it would come out sounding like Jimi Hendrix.

"I was playing a Strat through a Marshall with wah-wah pedal and Fuzz Tone, and it quickly became apparent that the result of trying to do this off-time stuff led to an unexpected parallel to what a lot of blues influenced people were doing in the 1960s.”

The solos appear to be improvised in the main this time...

“Almost every solo was improvised. Even those that sound like they have been written were improvised. The solo in Wet Sand, for example, is one of those things you can sing along with but it was totally improvised.

What’s the key to improvisation?

In polyrhythmic playing, where you’re finding your own groove inside the music and the hidden spaces between the music, you can’t plan out what you’re going to do. Take the guitar solo to Hey: I could only plan it out in the sense that I knew I was going to be constantly speeding up and slowing down. If you try to plan it the subtlest difference in the groove of drums and bass is going to change what you’re doing. During rehearsal we were playing stuff much faster than we ended up playing it in the studio, so the same solos weren’t working.

"So I really had no choice but to wing it in the studio. For me, this really gave the album a live quality and an exciting spontaneity that I haven’t had in the studio before. There is no more relaxing part of making a record than improvising solos. That’s just fun for me.”

"People pretend there’s an advantage to not learning theory, but I think they’re just lazy”

While you use theory to your advantage, many top guitarists claim they don’t know much about theory and play by ‘feel’ instead...

“Good luck to them. I have nothing against that way of thinking. In fact, I have more in common with that way of thinking than with people who normally get associated with theory. The people who inspire me when they talk about theory are [jazz musicians] Miles Davis, Charles Mingus, Eric Dolphy and Charlie Parker. These people didn’t play by feel and were thinking completely in terms of theory.

We are all playing by feel, but not in the definition of these ignorant guitar players who don’t want to spend time learning the theory. People pretend there’s an advantage to not learning theory, but I think they’re just lazy.”

Yet your solos were still improvised...

“As I told you, the most important thing for me is to shut off my mind. I don’t need to think that something is a minor 3rd to play a minor 3rd, but I know it’s a minor 3rd. The feeling of a minor 3rd is equivalent to a symbol I have in my head that means minor 3rd. It’s not very complicated, it just sounds complicated because people don’t use that language when they talk.

"It would be like somebody saying, ‘I don’t want to use words to talk, I want to just go by feel, I want to rub people’s bodies and I want to rub my penis all over them. I don’t want to talk.’ To me that’s just a useless, limited way of being. I like to talk to people and rub all over them.

I think theory gets a bad name because a lot of people use theory instead of feel. But Flea and I are both huge fans of those jazz musicians I mentioned, who seemed to grow throughout their whole life as musicians. But a lot of rock musicians who don’t think on that level often go through a decline within a few years. I’m not saying that’s the only reason, as quite often they overdo it with drugs and sex or dishonesty.

"If you’re a person who thinks theory is going to limit you then don’t learn it, but make sure you’re being honest with yourself and that you don’t want to learn it just because you’re lazy and telling yourself, ‘Yeah man, I play by feel,’ because that’s just being a pussy. Theory doesn’t block people’s creativity, only the ego blocks creativity. Excessive drug use or drinking can block it, but not theory.”

"I feel strongly that there is no drug or drink that makes anybody better than they really are"

It’s interesting that you say drugs and alcohol prevent creativity, yet many musicians throughout history have used drugs to aid creativity...

“Oh, you can do that. I said excessive drug use. Marijuana, mushrooms or acid have the ability to really open somebody up, but they actually do it from one time of taking the drug. If you have one good experience with those drugs you’ve altered your brain permanently for the better.

If the experience was bad you’ve permanently altered your brain in a bad way that might take years to correct. I believe that very strongly. When it comes to a drug like cocaine, I believe it takes a very special person in a very special environment during a very special period of time for this to be of any value, and I don’t count the present time as being one of those times.”

You’re drug free now [John raises his eyebrows]. Well, if not drug-free you certainly seem to have your drug use under control...

“For me, that’s the important thing. Since I’ve been meditating I feel very strongly that the highest peaks a person can reach are from resisting that impulse to just take something all the time. When you take drugs you’re essentially allowing your brain to do whatever it wants. The most important thing you need is to have some kind of contact with the person you are inside and to be honest with yourself. If you have that you don’t need drugs.

"The part of myself I’d been running away from was the Mother’s Milk time, because I felt as though I hated that person, hated his approach and hated the way he lived his life"

I feel strongly that there is no drug or drink that makes anybody better than they really are. Meditation can bring a person around. It’s hard as fuck and I had to go through some terrible shit at first. When I went into the studio to make this album my stomach was very painful and I felt that I hated myself all the time. The part of myself I’d been running away from was the Mother’s Milk time, because I felt as though I hated that person, hated his approach and hated the way he lived his life. I was looking at myself as a stranger who had invaded my own life.

During a meditation about three weeks into the studio time I finally realised I loved that part of myself, and from then on my knotting stomach went away and I kicked ass in the studio! I needed that part of myself to make this album.”

"We don’t make music just for our own pleasure, we make music for our audience"

It’s a controversial step to release such a large volume of music [28 tracks, overtwo hours of material] in one go? Do you have any reservations?

“No. To me it’s stupid that it’s controversial. If a painter decides to paint 40 paintings nobody says, ‘How can you paint 40 paintings? What gives you the right to make 40 paintings?’ Yet when it’s a song all of a sudden everybody says, ‘How did you think you could get away with this?’ But it’s what we did.

I’ll say the same thing The Clash said with Sandinista, the same thing The Beatles said with ‘The White Album’, the same thing Jimi Hendrix said when he wanted to make his fourth album a triple record: it’s what we recorded. It’s the music that came through us.

We don’t make music just for our own pleasure, we make music for our audience. If we write 28 songs that we think are top notch, that’s what we want to give to the public. That’s for mankind. Making music is my gift to mankind and it’s what I have to offer.

“You don’t put out 14 songs because that’s what critics would accept with a smile. We’re putting out what we believe is worthy. I can’t say that if somebody puts [the album] down it won’t hurt my feelings, because it will. But I can deal with it. What is important to me is that some kid somewhere, three years from now, could possibly hear one of these songs and decide not to kill himself. I’ve heard that plenty of times from people. People write to me telling me they fell in love to my music. How do I know it’s not going to be the 27th song on the album that’s going to do that? Why, just because we’re in the music business, should I have to shorten things to be like everyone else? Fuck that!

Business considerations don’t matter as much to us as it does to have the right artistic reasons for doing something. Luckily, our managers support us. When we said we wanted to do a double record they said ‘You know what, why not?’ Fuck statistics, we’ve made a good album so let’s put it out.”

"When we’re in the studio we get really precise about the tempo of things"

What were the concepts behind your guitar work on Stadium Arcadium?

“I started getting particularly excited about anyone who was doing any kind of off-time stuff, and I would try and get everybody else into the same kind of movement as me. We [RHCP] would have arguments about it. If it was up to me, Dani California would have been slowed down about three clicks a minute more than it was.

When we’re in the studio we get really precise about the tempo of things. With Chad [Smith, drums], we can argue about one beat per minute. Our arguments were always that I wanted to drop so heavy that it would slow down. For example, on the She’s Only 18 chorus the whole feeling of the chorus is much slower than what you would imagine coming from the verse. With the Dani California chorus, you will notice that the last chorus slows down even more than the first two. I was just interested in playing with rhythm.”

What was the writing process?

“When we were rehearsing for this album, I was probably listening and practising with my guitar for about five, six, seven hours a day. A lot of the music for this album came from me just playing and playing. A lot of what I was listening to was hip-hop, so I was playing bass along with it and then I would pick up my guitar and play for an hour and just see what came out. I have the patience to play the same thing over and over on my guitar until something new comes into it from meditating."

Did you use any new equipment for this particular album?

“I bought a bunch of different wah pedals because there were so many moments on the album that were going to have wah-wah that we didn’t want them all to be the same. My favourite one is still the Ibanez [WH-10] one, which they don’t make anymore, the bastards! Omar [Rodriguez-Lopez, of Mars Volta] is now addicted to them and he’s buying them up all over the place.

"The Dimebag model [Jim Dunlop Dimebag Crybaby From Hell DB01] wah pedal was another one that I used on certain spots on the album. I don’t like it as much as the Ibanez, but it’s the best that I’ve found.”

Do you know how you’re going to alter sounds before you’ve played them or is it an organic process?

“Sometimes I’m experimenting with the modular synthesizer, and sometimes have the sound clear in my head so I know exactly what I’m setting out to do. Some effects are impossible to control, like the new MuRF pedal by Mooger Fooger. It’s basically a series of 10 filters that go in a rhythm and you can turn up each frequency at any moment. I used that on the solo at the top of the second verse in Dani California, and I also used it on Flea’s [RHCP bassist] trumpet on Death Of A Martian.”

GUITARS

1961 Fender Stratocaster (white), 1962 Fender Stratocaster (sunburst), 1969 Gibson Les Paul

AMPLIFIERS

200-watt Marshall Major, Marshall Silver Jubilee

EFFECTS

Mooger Fooger MuRF pedal, Boss Chorus Ensemble, EMT 250 digital reverb, Electro-Harmonix, POG (Polyphonic Octave generator), Electro-Harmonix English Muff ’n, Electro-Harmonix Big Muff, Boss DS-1 and DS-2 distortion, Ibanez WH-10 Wah

Guitar players are not going to be disappointed with this record. Turn It Again, for example, seems to have around five solos going on at once...

“That’s right! Another thing I did on this album, which comes in a little on that track, is tape speed manipulation. The idea with that solo was to have a lot of guitars coming in and out, and that was one of the few sections I mixed myself.

There were so many tracks of solos, the engineer had no idea what to do with them so I went in and figured out how I wanted them to be orchestrated. There are five cycles in two minutes and I approached each section differently, with regards as to which guitars to feature. I did some Jimi Hendrix stuff where I turned things up and down with the faders while they were playing.”

Did you just fire off a load of guitar solos and then decide what to do with them afterwards?

“Yeah, I did some with my friend Omar [Rodriguez-Lopez] sitting on the couch listening to me play solos. I did some at my house a couple of months later. I knew I would figure it out during the mix. Brian May and Jimi Hendrix both did really cool things in this way, and doing it myself made me hear the way they were doing it in a new light.

"That thing at the end of Wet Sand – where the guitars come in and sound like a harpsichord – they’re just the treble pickup of a Stratocaster, three tracks in harmony with one another, playing that same riff you hear in the first part of the cycle of that section. But I recorded it with the tape slowed down, so that when it’s sped up it sounds like a harpsichord.

"When I went home and listened to Burning Of The Midnight Lamp by Jimi Hendrix it had the same sound and, despite the Jimi Hendrix box set saying it was a harpsichord, I’m positive it’s a guitar that’s sped up.”

How important were your solo albums in getting you to this stage?

“Very important. That was where I learnt how to use the studio like an instrument. Up until that point, I was still letting the engineer tell me what to do. On my solo albums I worked with my friend Ryan Hewitt who is a young engineer ready to experiment. We began a relationship where, starting with The Will To Death [2004], we decided to do everything differently to how we were seeing it done around us.

“By the time I was doing my overdubs for this record with Ryan, we just had it ‘down’. On this album we actually had 72 tracks, because we had to have a 24-track machine for the basic tracks, a 24-track machine for the overdubs and treatments, and another 24 for backing vocals, so when we were mixing there were three 24-track machines all sync’d up with each other. I needed my solo albums to be able to get to that point.

"Now when I’m in the studio I’m in control of what’s going on. The engineer asks me what tracks to use.”

"You can hear it when Anthony starts singing: there’s a little commotion going on where I stop playing the riff for a second and you hear the sound change"

Are you a perfectionist? Do you find it difficult to know when to stop when it comes to the studio?

“Well, another part of my concept for this album was to make it more raw and to let certain mistakes fly. If you listen to Especially In Michigan, I had my guitar on the wrong pickup. I like the way that riff sounds on the bass pickup, but when I was playing the song I looked down and it was on the wrong pickup.

When Total Guitar ran a poll to determine the worst guitar solo ever recorded, Californication's high placing raised eyebrows. But John's reaction may change the naysayers minds…

"I understand why it might not be popular. My concept for that solo was to do something like Tom Verlaine. I used a cheap, thin sound. Not the kind of sound that’s attractive to guitar players, who prefer Jimi Hendrix’s or Eddie Van Halen’s sound, which have a certain thickness to them. Tom Verlaine was the opposite of that, which is why I loved Tom’s playing.

"I was experimenting with that sound, with lots of space, and I don’t consider that to be guitar player-like guitar playing. However, when I play it in front of 20,000 fans they all go crazy for it!

“So I think it’s a guitar player thing rather than a people thing. I can suggest to those people who voted that the disconnection one feels to a solo like that comes more from the person who’s perceiving it rather than from the guitar player, because I’m in there with the flow of the music. That solo has a beginning, a middle and an end, and to me that qualifies it as having some worth.

The fact that I’m doing it with no power might be offensive to some of the listeners, but I haven’t always tried to be good in the eyes of guitar players. What’s more important than to speak to guitar players is to speak to people. If you can do both, great.”

"You can hear it when Anthony starts singing: there’s a little commotion going on where I stop playing the riff for a second and you hear the sound change, then a little white noise for a second. I’m happy to leave it like that because it gives the recording personality.

"That’s the kind of shit they would leave in during the 1960s but take out in the 1980s. Which time period was better? The Rolling Stones’ recordings in the 1960s had the tambourines and the drums going off on different times with each other; the guitars go off time with each other then come back together and it’s beautiful. That’s what gives it personality and a magical feeling. I am a perfectionist, but for me those kinds of accidents are part of perfection.

How often do you practise playing?

“I was playing scales every day during this album. I was trying to make my pinky as strong as my other fingers. I was inspired by reading Robert Fripp articles where one of his main points is that the pinky is very messily used by players and that few people have it under control.

"The pinky exercises have changed the way I play in many ways. There are a lot of guitar parts on the album where the pinky is being used as equally as the other fingers in simple arpeggio-type things. That gave my playing a strength and power that it wouldn’t have had otherwise. There’s no better way to spend the day than to sit around practising. That’s when I feel the best.

"When we’re on tour I pretty much have the whole day to do what I want. Once the tour starts, I hope to go back to practising four or five hours a day. Now that the album’s done, our object is to fucking rock the hardest we can and to be the best band that we can be.”

What would you do with your time if you couldn’t play guitar?

“I’d just meditate all the time! When you start meditating you start desiring a lifestyle that assists your ability to meditate. If I had never been able to play guitar I’m sure I’d be doing something else creative. I have fun painting, but it’s not something I have a natural aptitude for.

Writing words was something I felt capable of right from the beginning, so I might have been a writer. You have to work at something for a while until you realise if you have any natural ability or not. In my case, I never seriously thought I’d do anything other than play music. By the time I was 12 I was serious about guitar, so I practised as much as I possibly could. I didn’t think about having something to fall back on, I was going to play guitar and that was that. If you consider even for one second that it might be a mistake, you’re finished. There can’t be any doubt.”

5 songs guitarists need to hear by… John Frusciante

“Every note counts and fits perfectly”: Kirk Hammett names his best Metallica solo – and no, it’s not One or Master Of Puppets

“I can write anything... Just tell me what you want. You want death metal in C? Okay, here it is. A little country and western? Reggae, blues, whatever”: Yngwie Malmsteen on classical epiphanies, modern art and why he embraces the cliff edge