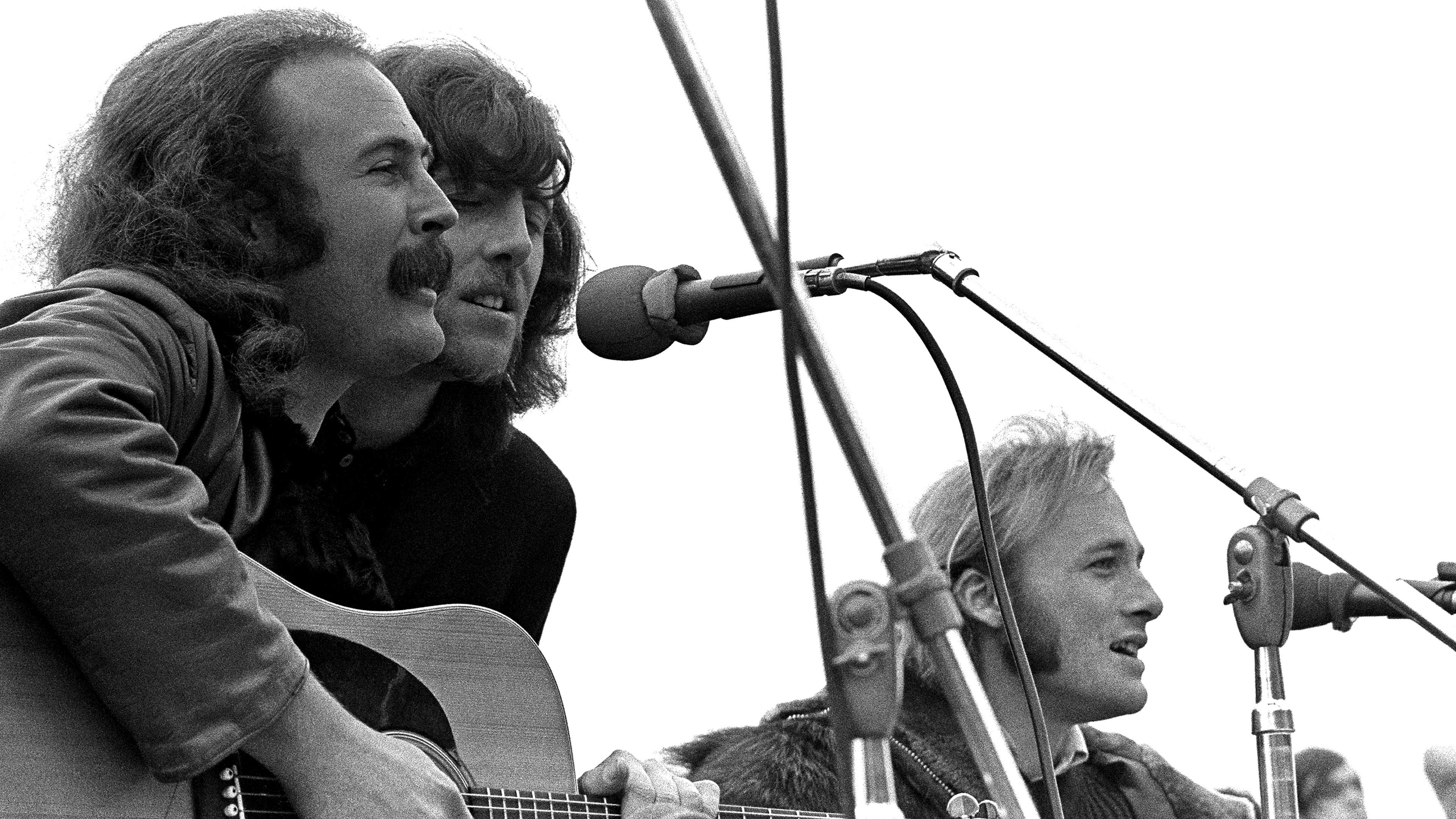

Byrds and Crosby, Stills & Nash co-founder, vocalist and guitarist David Crosby has passed away at the age of 81. We were lucky enough to speak with him in 2012, when he took us through each track that made up CSN' eponymous debut LP.

"The term 'supergroup' didn't exist until we formed," said David Crosby when we met in 2012, recalling the time in 1968 when the ex-Byrds singer and guitarist joined forces with former Buffalo Springfield guitarist and singer Stephen Stills, and Hollies vocalist and guitarist Graham Nash.

It was the year of the guitar player – Clapton and Hendrix. Everybody wanted to go in that direction, and we had this completely different thing

"We were the first second-generation band to form. We had all been in successful bands before, but something like us had never happened. We set the precedent. And for us to become even bigger than our previous bands, that was even more unique."

Crosby was already well acquainted with his soon-to-be bandmates, but it took an informal jam at the house of Mamas And The Papas' singer Cass Elliot's to indicate that lightning could be captured in a bottle by a blend of their three voices.

"In a sense, we knew what we were after," Crosby told us in 2012. "I had heard Stephen's songs, and they were great. He was the up-and-coming young writer in LA. He was the guy with the best songs. So I started singing with him. [Sings] 'In the morning when you rise…'

Nash, hanging out nearby, came over and asked the two to sing the song (what was to become You Don't Have To Cry) again. "Stephen and I looked at each other and said, 'OK, sure,' and we sang it again," Crosby remembered.

"When we were done, Nash said, 'Can you do that one more time? Just one more time.' The third time we sang it, Nash joined in and added a top harmony line. It was amazing! It really was."

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Nash, already disillusioned with the creative direction of The Hollies and their lackluster reaction to the new songs he was writing, quickly turned in his walking papers to the British pop group and set about recording an album with his new mates. The resulting record, an inventive mixture of folk and light rock highlighted by the three's supreme vocal harmonies, ran counter to the musical flavor of the time.

"It was the year of the guitar player – Clapton and Hendrix," said Crosby. "Everybody wanted to go in that direction, and we had this completely different thing, even though Stephen was a really fine guitar player. We wanted to do this thing with our voices, because it worked. And we had songs – really good songs. We knew we had our own sound."

Released on 29 May 1969, the album Crosby, Stills & Nash was an immediate smash, spawning two radio hits (Marrakesh Express and Suite: Judy Blue Eyes) and creating a massive shift in popular music, one which would place an emphasis on harmony-laden songs.

Although the trio of Crosby, Stills & Nash would occasionally include a floating member, Neil Young, for the lineup of Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, the supergroup that formed in Cass Elliot's living room survived and thrived through countless personal dramas and musical changes over the years.

Suite: Judy Blue Eyes

“Stephen was writing it when we started joining forces. He had some pieces of it. Then he met Judy Collins, and that’s when it became Suite: Judy Blue Eyes. I’m sure you’ve seen Judy Collins’ eyes, which are rather spectacular. It was several pieces of different songs, and Stephen hooked them together in an extremely powerful way.

“We have a sort of built-in arrangement sense – it’s a chemistry between the three of us. We’ll try things, but we usually know right away what is the right way for a song to go. When we started doing harmonies on the song, we’d start on the same note and then slowly split apart as we went up. [Sings] ‘It’s getting to the point’ – we’d all start on the same note and spread out. Stuff like that became our modus operandi.

“We recorded it at Wally Heider’s old studio in Hollywood, a funky little room. We did this one all in the space of a few days. There’s a funny story about it, though: When we got to the end of the record, we were listening back to everything and Stephen said, ‘The song’s really good, but I think we can beat it.’ We said, ‘You’re crazy.’ But he was serious – ‘No, I think we can do it even better.’

“And so, over the course of two days, we recorded the entire seven minutes and twenty-two seconds of it over again. The entire thing, from scratch, another version. After we were done, we played them back, and we had to say, ‘Nope. We did not beat the first version.’ The first one had the mojo.”

Marrakesh Express

“This is why The Hollies lost Nash. He was writing songs like this. If they had realized how good his songs were – Right Between The Eyes, Lady Of The Island, Marrakesh Express – I don’t know what would have happened.

“The song changed when we recorded it. We made it kick ass, and we made a great record out of it. Stephen played incredibly inventive guitar stuff. And you know, he’s a great arranger. When Nash sang us Teach Your Children, it was a little folk song. Stephen said, ‘No, no. That needs to be a country song – like this.’ And he changed it into what it is now.”

Guinnevere

“It’s three women – three verses, three different women – one of whom is Joni; one of whom is Christine Hinton, my girlfriend who got killed; and one is another girl whose identity I promised I wouldn’t reveal.

“You know, it’s hard to judge your own work, but I think this might be my best song – although I’m still trying to beat it. [Laughs] Musically, it’s really intricate and delicious. It goes 4/4, 6/8, 7/4, each verse in a sequence. I didn’t know it until one of the Grateful Dead guys said, ‘Did you ever count that?’

“I like it musically, I like it lyrically, and I like the mood that it creates a lot. The guitar pattern, I can’t say how it came about. I just fooled around and it came out. It’s in a very odd tuning that a guy from the Midwest showed me one time. Nobody really owns tunings. I’ve shown it to thousands of people over the years, and they went off and wrote their own songs.

“I do think this one is beautiful. It could be my best.”

You Don't Have To Cry

“The first song I sang with Stephen. Then Nash put on his harmonies, and it was, ‘Ahhh! Now we know what we’re going to be doing for the next few years.’ The harmonies carry the song, and they do a lot of non-parallel things. That’s our forte. That’s what we do.

“The song was too short, so I told Stephen, ‘Just sing it twice.’ He looked at me and said, ‘You think we can get away with that?’ ‘Yeah, sure,’ I said. ‘When you get to the end, just start it over.’ So we did it like that, and it worked beautifully. I don’t know it anybody ever realized it, but it’s the same song twice.”

Pre-Road Downs

“A Nash song after he realized that he could write rock ‘n’ roll – fierce rock ‘n’ roll. The backwards guitar is Stephen being a freaking genius. This is real backwards guitar, and how he got it match up to the forwards stuff, I have no idea. He did it, and we looked him and thought, This guy is from fucking Mars! I’m still freaked out by it.

“Cass is on it. She’s in the stack of vocals that go [sings], ‘Hotels and midnight coaches/ be sure to hide the roaches.’ She’s the only person who sang on the record besides us, and only on that one song. We loved her so much, all of us. She was a great human being. So funny... and just one of the best people ever.”

Wooden Ships

“Paul Kantner [of The Jefferson Airplane] and I were really good friends. We were folkies, we lived together – this was before I even met Stephen. When I got kicked out of The Byrds, being told dramatically that ‘we’ll do better without you’… [laughs] – I shouldn’t take such pleasure in that…. So I had this boat down in Florida. Everybody could come visit, come sailing. Paul and Stephen showed up at the same time.

“I had that set of changes. They’re pretty unusual, I must say. Stephen added to them, but the main changes I had. We started goofing around with them, and we all wrote the song. Later on, Paul called me up and said that he was having this major duke-out with this horrible guy who was managing the band, and he was freezing everything their names were on. ‘He might injunct the release of your record,’ he told me. So we didn’t put Paul’s name on it for a while. In later versions, we made it very certain that he wrote it with us. Of course, we evened things up with him with a whole mess of cash when the record went huge.

“It’s a post-apocalyptic story. The world has gone to hell. ‘Silver people on the shoreline’ is radiation food. The idea was that we were sort of sailing away from that madness. It’s the song that Jackson [Browne] wrote For Everyman in response to. It’s him saying, ‘Hey, we don’t all have a sailboat to sail away in. We have to stay here and fix it for everybody. That’s a fantasy that you’re writing.’

“The guitar parts… we just played ‘em. We’d try things – ‘Oh, that sounds good.’ It wasn’t an intellectual exercise.”

Lady Of The Island

“Another perfect example of why Nash had outgrown The Hollies and needed to move on. It’s so much more adult and genuine than the pop music that he was making. Not that that stuff wasn’t good – they made great records. They had more hits than all of us put together. But he needed a change. The Hollies didn’t understand the songs he had started to write. We did.

“It’s about a specific person, a married woman who found herself susceptible to Graham’s charming self and was unable to resist temptation. It is a matter of historical fact that a great number of women were unable to resist Graham’s charming self. He was so extremely good looking...

“It gets a little embarrassing. It wasn’t quite like sharks on sheep, but we did make love to a great number of beautiful women. I’m just telling the truth. In this case, however, it was an affair that had some meaning and depth, and a very beautiful song came out of it.

“I really like improvisation that Nash and I did on this. What we’re doing in and around the melody, none of that was structured. I know I was just winging it, but it worked. The way our voices blend, it’s who we really are, and we’ve been that way since the beginning. We’re like two spitfire pilots who know where each other’s wing tip is. You can’t miss that image."

Helplessly Hoping

A classic Stills song, but it’s one with a lot of alliteration. Really skillfully done. It’s this kind of writing that made me want to be his partner. And the picking – everything he does on the guitar is so freaking right.

“Again, you hear that there’s a non-parallel element to the harmonies that’s… delicious. Rather than contrapuntally, the harmonies move together. But they’re not the standard triad movement. Everybody else who started doing harmonies after we came out would do the root, the third and the fifth. That’s what they knew. But we would be moving – especially me. I would be creating suspensions and resolves. Nash did that, too. It creates tension and release.”

Long Time Gone

“We do it live better than the record. We kick its ass into next week. I guess it's kind of blues, but if you’re in a band with Stephen Stills, you really don’t want to be singing the blues, because he’s drastically better at it than I am. [Laughs]

“Whatever it is, whether it’s blues or not, I like it. I liked it when I did it. We’ve improved it over the years. Things have evolved with the arrangement – we change arrangements all the time. We’re constantly finding new things in our songs and going somewhere different.

“Some songs we cut live, but this one was a construction, because everything else on it was Stephen, including the organ. He’s got a style. He doesn’t play it much anymore, but he definitely had his own style… and it worked.”

49 Bye-Byes

“I haven’t the vaguest clue what the title refers to. Like with the song Page 43 [from album Graham Nash David Crosby, 1972], people come up to me and they’re sure they know. One guy said to me that it was from page 43 of the Bahá'í book. He was sure that I was a Bahá'í. I had to tell him, ‘I don’t even know what the Bahá'í is.’ And he was like, ‘No, no, no. You sang it.’ I told him, ‘No. It’s my lucky number. That’s what it is.’ He was very distraught.

“I don’t know if Stephen knows what this title means, either. It was just fun to sing. The music, it’s Stephen again taking pieces of things and weaving them together skillfully. He could have made two or three songs out of it. It starts out gentle, when it’s in the 6/8 part at the beginning. But that’s just like Steven to turn it into something else. He did that in the Suite, too. He makes parts go together in ways that other people wouldn’t have thought of.”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track

“Part of a beautiful American tradition”: A music theory expert explains the country roots of Beyoncé’s Texas Hold ‘Em, and why it also owes a debt to the blues