Classic interview: Buddy Guy – "If people come see you, I think you should give them every damn thing you’ve got"

From his childhood on a plantation to being discovered by Muddy Waters and inspiring Clapton; a blues legend looks back

In 2015 Buddy Guy spoke to Total Guitar ahead of the release of his album, Born To Play Guitar. In a wide-ranging chat, he looked back on an incredible career so far.

When blues gods walked the earth, Buddy Guy was among them. Now he’s one of the last of his kind - this is the life of a living legend, in his own words.

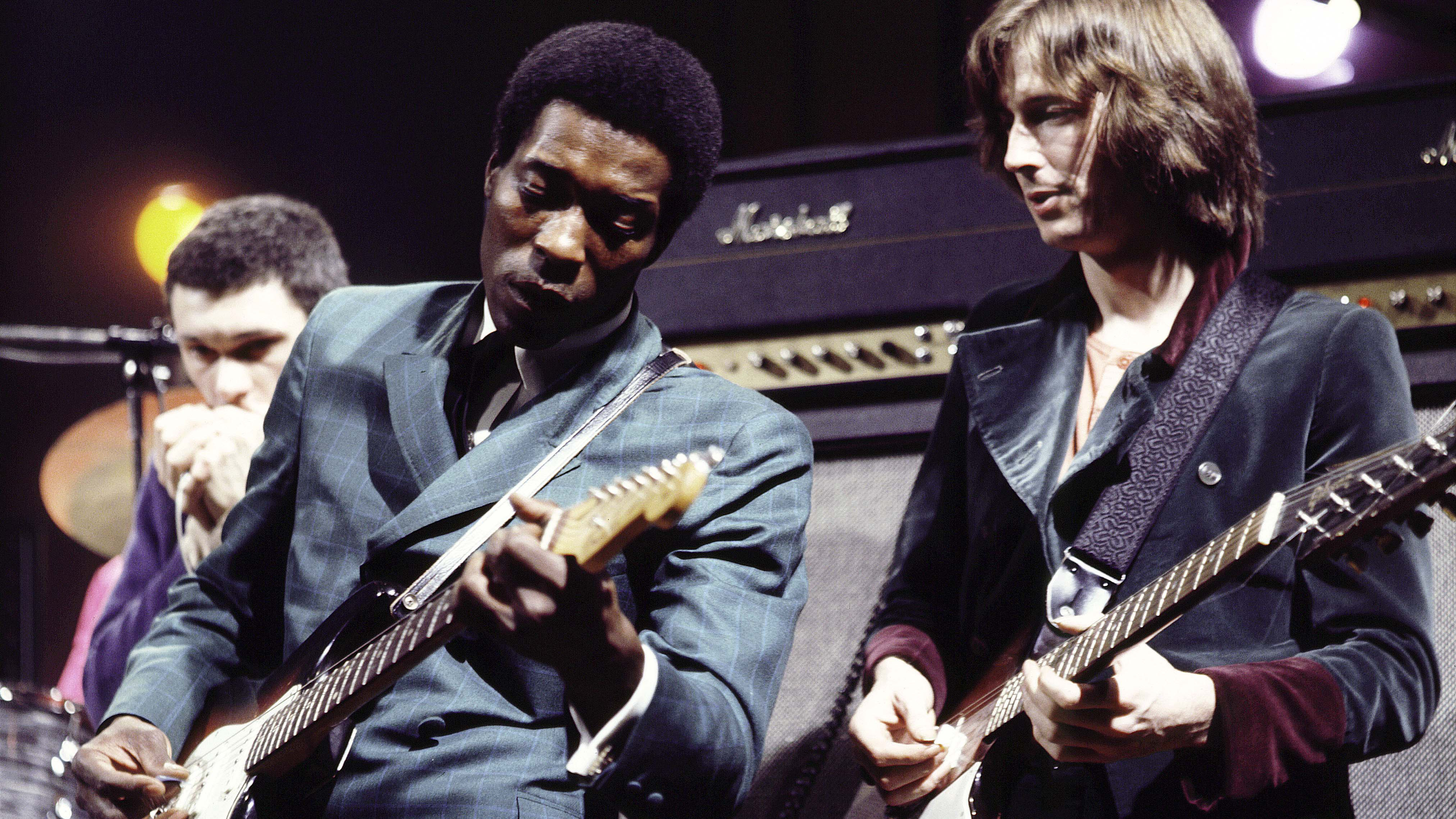

Before Clapton was Slowhand, before Keef was The Human Riff and before Jimi took over, there was Buddy Guy. The guitarist is one of the last great bluesmen.

A man raised on a plantation without water and power, who started off playing rubber bands and wound-up honoured by a president and who, in the 1960s - still unknown to mainstream US audiences - was surprised to discover a fanbase of rabid young UK rock stars worshiping his work from across the Atlantic.

If Clapton is god then Buddy Guy’s the holy spirit. The embodiment of the original grit-laden Chicago blues boom, Guy’s instrument-hurling stage theatrics, sublime touch and anarchic, scything Strat tone shaped the playing of everyone from Jimmy Page to Jeff Beck.

Here we talk to the all-round nice Guy and hears a tale of gun-toting promoters, Rod Stewart’s valet career and one man’s enduring love of the electric guitar.

What inspired you to play guitar in the very beginning?

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“Well I was born on a farm, what you’d call a plantation, in Louisiana and I used to just try and take rubber bands - anything that could get tight enough to make noise - I would be bothered with it. My dad’s friends used to tell my dad, ‘You know, that boy could be a musician.’

“But of course, back then, a musician was just a musician and there wasn’t such a thing as making a decent living out of it. So my mama would get a catalogue in once in a while and I would see what a guitar looked like.

“There was one guy who could play a little Lonnie Johnson and stuff, they would bring him through every Christmas with his little acoustic guitar [to play]. They would have a few drinks of wine and they would go to sleep and I’d pick up his guitar while the other kids were playing with their Christmas toys. I never did play with mine - I always wanted to play that guitar.”

When did you put down the rubber bands and pick up your first guitar?

“Well my dad finally got one of those little acoustic guitars [diddley bows] from that guy they would get in every Christmas. He was sawing logs, what you call lumber, [for extra money] and I think dad gave him a couple of bucks for that guitar one year, I think it had two strings on it. I messed with those two strings and broke them and spliced them with my mother’s hairpins and any other wire I could tie.

“Then I went to school in [Louisiana state capital] Baton Rouge and a stranger walked by every evening and saw me outside [playing] and doing my homework after school. He said, ‘Boy, I bet if you had a guitar you’d learn how to play!’ Then he asked me, ‘What do you do on the weekend?’ He came by the next weekend and took me downtown and bought me a brand new Harmony guitar. His name was Mitchell and I found out later that he and my dad grew up together.”

How old were you when you arrived in Chicago for the first time? What were your first impressions or memories of the city?

“I knew who was there. I was 21 years-old, I probably would have went there earlier but they told me I couldn’t get in to blues clubs unless you were 21 years-old. There was Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Lil’ Walter, they were there in Chicago and Chess Records had exploded the blues in America, what you call the ‘Chitlin’ circuit.

“I didn’t go there thinking I’d be good enough to play, I just wanted to watch these greats playing - Muddy Waters, Sonny Boy [Williamson], all those guys - and I got stranded.

“Someone I had played for trying to earn my train fare back to Louisiana said I could play and I got discovered by Muddy Waters. He came and saw me in the year I was 21 and said, ‘You can play well enough. Play with us tonight.’ Now I’m here [in Chicago] and they’re gone and I owe that to them. I promised him that I wouldn’t go back [to Louisiana] after he was so nice.”

"They all were telling me they didn’t know a Strat could play the blues and I laughed and said, ‘What do you mean!?’"

Like many of the blues greats, you later developed a big fanbase in the UK. When did you first realise that you had a substantial following here?

“I didn’t realise it! I was invited there in February of 1965 and I toured with The Yardbirds and Rod Stewart was the valet. I didn’t know who Clapton, Beck, Jimmy Page, none of them was. They all were telling me they didn’t know a Strat could play the blues and I laughed and said, ‘What do you mean!?’

“Because they were all looking at the Gibson guitars and when they saw me, I went in there with a Strat and was playing them in a kind of wild and crazy way, and I was doing some of the things that I would do like throwing it up and catching it. I was amazed for them to tell me that they’d sat there and watched me and didn’t know the blues could be played like that on a Stratocaster.”

The best Strat guitars you can buy right now, from budget to pro

You’re well known for your love of Strats. What is it about the Stratocaster that captured your imagination?

“The first time I ever saw one I think was with the late, great Guitar Slim. He was in New Orleans playing it. The acoustic guitars, you’d leave them in the weather, or somebody could step on it and crack it.

“I saw that the Strat was a solid piece of wood and I wanted to act like Guitar Slim and [I knew] if I dropped it wouldn’t do nothing but scratch it. It would take so much wear and tear compared to the other guitars, so I just fell in love with that.

“If you’d see me play, I wanted you to say, ‘He’s playing his guitar like he don’t care whether tomorrow comes.’ Because if people come see you, I think you should give them every damn thing you’ve got. I knew the Strat could give me that and I’ve been in love with it ever since. It just stuck to me.”

“And he pulled a gun out and said, ‘I told you… I didn’t make no money’"

You’ve played thousands of shows, but what’s the worst or strangest gig that comes to mind?

“Oh wow! I’ve played quite a few of them! Back in my early days I played a gig and I saw the guy had a house full of people, but I wasn’t getting no pay whatsoever, I didn’t even have a car. So I went in to get paid and he told me he didn’t make no money! I said, ‘Well, you had a lot of people!’

“And he pulled a gun out and said, ‘I told you… I didn’t make no money.’ I said, ‘Well, I don’t argue with a gun.’ I just left and tried to find somebody to take me back home! There’s been a lot of strange things happen. I could go on and on until next year telling you about that kind of stuff!”

“I guess that would have to be when I got introduced to Muddy and BB King and all of those great blues players. When they found out I could play a few notes, they showed up and I got nervous and I didn’t want to play because I recognised them.

“I was trying to ignore them, but when I came off stage they just grabbed me and said, ‘Come here!’ And they sat me down and, you know, said, ‘You’re good enough to join us.’ And that’s one of the things that I will take with me for the rest of my life.”

“I learned how to play for the love of music, not the love of money"

It’s lucky, in some musical circles, they might have viewed you as competition…

“For sure. That’s why when young kids come up to me now, I reach out a hand, because I needed it. I was very shy. I was shy playing any place, especially in front of Muddy Waters, or BB King, or John Lee Hooker!

"And I’m like saying, ‘Well why should I go up and play guitar? These are the people I learned everything from. I’m not even supposed to show up…’ I would treat it like that. So now I try to hand it down to young people who ask for some advice.”

What’s the toughest time you’ve had as a guitar player?

“Oh man, I remember, coming up on 40 years ago, I was watching TV and they had these predictions for sports and music and they said, ‘I don’t care how good you are, in sports and music, only five per cent are going to make it.’ [Even then] I looked at that and thought, ‘My god, I don’t think I’m in the five per cent!’ But I loved it so well, I didn’t quit.

“I learned how to play for the love of music, not the love of money and then it just happens. I tell all of the kids right now, ‘Go for it. If you make it, fine. If you don’t, you don’t.’ It’s like a prize fight, if you’re in the ring with gloves on and you lay down, you’ve got no chance to win, but if you keep swinging, you might get a lucky punch.”

“A lot of musicians went on to all different kinds of drugs to make you feel like you wasn’t tired, even if you was, and I didn’t go for that."

You look great for your age and you’re still playing superbly. What’s your secret?

“I just didn’t let a little success go to my head and make me feel like I was supernatural and didn’t need to sleep, didn’t need to eat, didn’t need to take a shower. And I didn’t let that bother me.

“A lot of musicians went on to all different kinds of drugs to make you feel like you wasn’t tired, even if you was, and I didn’t go for that. I tried to take care of myself, because I’m not a superhuman just because I learned how to play guitar. I’m just another person and if I get scratched, I bleed.

“I knew quite a few who were close friends of mine and once they got a good record out, they went strange. Some of them forgot who the hell they was. I looked back then and thought, ‘If I ever get a pretty good record out, I don’t think I could do that. I always have to recognise what I came from.’”

What’s the best advice you’ve been given?

“It was by BB King, god rest his soul. I got to know him and I would always complain [about press reports]. He looked at me and said, ‘Buddy, you’re gonna get bad reports and good ones, but you just remember one thing here: when you get a bad report, at least you’ve made the paper!’ [Chuckles] And I said, ‘That’s a different way to look at it!’

“I guess my advice is that if you love it the way I love it - and if you’re playing well you have to love it - just keep on playing it. A lot of people criticise the blues, but I tell them: ‘If you haven’t had the blues, just keep living.’”

Matt is a freelance journalist who has spent the last decade interviewing musicians for the likes of Total Guitar, Guitarist, Guitar World, MusicRadar, NME.com, DJ Mag and Electronic Sound. In 2020, he launched CreativeMoney.co.uk, which aims to share the ideas that make creative lifestyles more sustainable. He plays guitar, but should not be allowed near your delay pedals.

“Every note counts and fits perfectly”: Kirk Hammett names his best Metallica solo – and no, it’s not One or Master Of Puppets

“I can write anything... Just tell me what you want. You want death metal in C? Okay, here it is. A little country and western? Reggae, blues, whatever”: Yngwie Malmsteen on classical epiphanies, modern art and why he embraces the cliff edge