Classic album: Seefeel - Succour

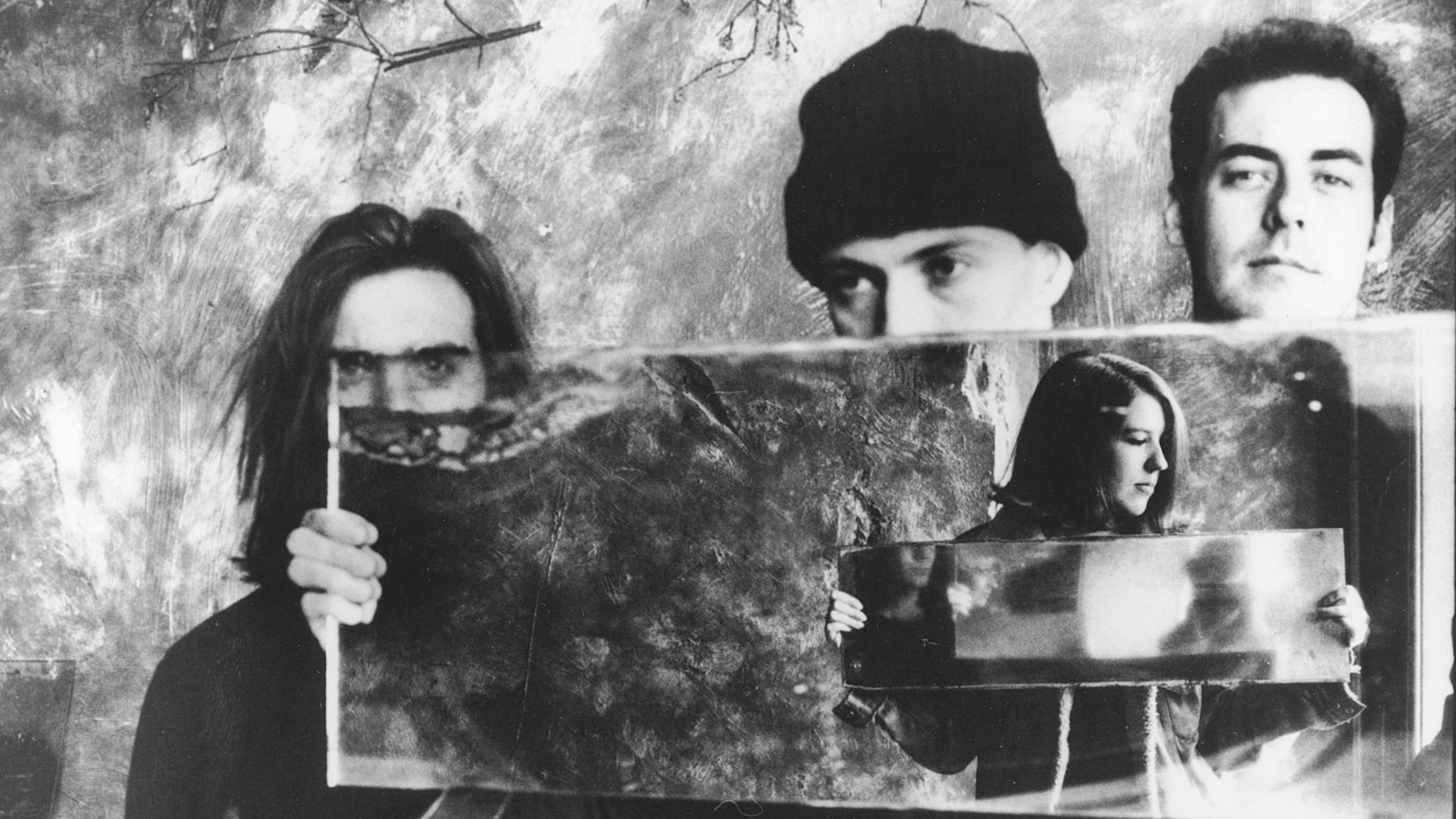

The members of Seefeel open up about how they produced their experimental post-rock opus Succour

For their second album, the shoegazing post-rock guitar experimentalists, Seefeel, took a doomier turn. Disembodying vocals to haunted snatches, and embracing a more claustrophobic and electronic tone and tension.

On their debut, 1993’s Quique, a fusion of guitars and machines was there. But a diet of post-production partying gave the music a dreamier pulse.

“On the first album we were going to clubs and doing pills. And everything was like a hands-in-the-air honeymoon period,” says guitarist and programmer, Mark Clifford. “Then it got darker.”

Alongside Daren Seymour on bass, Justin Fletcher on drums, and vocalist Sarah Peacock, Clifford channelled the comedown mood, soundtracking it with dense sonic textures, and swashes of twisted sound and noise manipulation.

“I spent a lot of time on the [Ensoniq] ASR-10, just feeling it out and sampling,” says Clifford. “I never read the manual. I don’t like to learn like that, because then you’re not controlled by the way you should do things.

“That was always how we did things in Seefeel. When we used studios, engineers would look at us like, ‘What are they doing?’ Because we’d do things that weren’t in their rulebook. To me that’s how interesting music is made, always has been.”

The resulting album, recorded largely between their basement flat in South East London and the Cocteau Twins’ September Sound studio, was also the band’s first on Warp.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“Not that we suddenly went out and bought synthesisers to fit in,” says Clifford. “We liked all that stuff before. It wasn’t like, ‘Oh yeah, we’ve moved to Warp, so we’ve got permission to sound like it’ [laughs]. There are no synths on Succour. We were still a very guitar-orientated band.”

Working late into the night, tracks would be built from the rhythm upwards, dictating the guitar noise, washed through effect pedals. Any vocals would be added last by Peacock, riffing and repeating undecipherable phrases.

“Full lyrics just didn’t work in that context,” she says. “There was no verse/chorus or traditional vocals. That doesn’t really work with that music. Everything was really transitional, then. We were at a turning point. It was all a new direction.”

That was a bathroom vocal – it had the best acoustics [laughs]. I would turn the lights off because the extractor fan ran whenever you had the lights on, so I was always in the dark

“The album was made at home in Blackheath, London, in the basement flat. And then some of the work was done at September Sound, which was the Cocteau Twins’ studio, as well. I hasten to add, though, not in their palatial main studio.

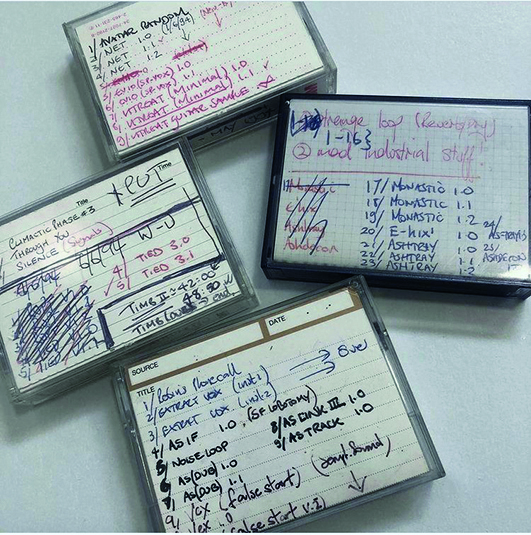

"The studio gear consisted of the Ensoniq ASR-10, which was the sampler we used, and the most important bit of kit. It had a high quality/dirty sound to it – a crunch. Then some ARP Avatar, and a ADAT digital 8-track that you used video cassettes with to recall multitracks.

"On the first album we’d used a Tascam, so that was like a major jump forward, to physical tape. Then the Atari ST, running Cubase. The [Ensoniq] DP/4 FX, which was a big, big deal. Plus, all the [Roland] GP8 FX that were mostly used for Sarah’s vocals. It was a simple, flexible setup, because we were using SMPTE, and were able to sync the sampler to the ADAT as well.”

Track by track

Meol

Mark: “We used the Electro-Harmonix Attack Decay pedal on this one a lot. It created these kind of long decays of the guitar. I can remember recording lots and lots of guitar, and then repeating certain phrases I liked, and then just adding some slight pitchshifting on some of them. I would have just used the sequencer in Cubase, after that.

“We didn’t make it as an album opener. When we were writing the tracks, there was no sense of, ‘that’s the killer opener’. Or, ‘that’s the single’, or anything like that. As there’s not much pace on the album, in terms of the tracks, it seemed the best way to create pace was to start with something that, well, had no pace, basically, and that’s this one.”

Extract

Mark: “This one was pretty much done in the [Cocteau Twins’] September Sound studio, as I remember… Sarah has got a much better memory than me.”

Sarah: “It was. You used that little guitar-loop thing. And I think the vocals were quite off-the-cuff there, too. This actually does have some lyrics. It’s just, ‘No way through. No, no way through’.”

Mark: “Everyone thinks it’s, ‘Love’ [singing it].”

Sarah: “No. It’s not that positive [laughs]. When it came to vocals, it’d be pretty much the last thing to go on a track, as well. I’d just usually riff about with ideas, and if anything got looks of approval, then we’d try and stick with it.”

Daren: “There was quite a lot of nodding at you, on this. Yeah, we used to nod a lot.”

When Face Was Face

Sarah: “That was done more at home, I think, cuz that was a bathroom vocal – it had the best acoustics [laughs]. I would turn the lights off because the extractor fan ran whenever you had the lights on, so you don’t want that, for noise, so I was always in the dark. There’s definitely the Attack Decay pedal on the guitars, as well.”

Mark: “I still don’t know if it was bust, but it gave us really broken sound on the guitar – it kind of stuttered a lot.”

Sarah: “Like a really erratic tremolo.”

Mark: “Yeah. On its own it was a little bit harsh, but once you put it through some filter and reverb, it had this really beautiful sound to it. When Face Was Face and Fracture both have that kind of funny, stuttery guitar on them.”

Fracture

Mark: “Whereas the last one was done at home, we got given a studio in Greenwich for this. We did a remix for a friend, and in return they gave us a day in their studio. My memory is of it being played at a really loud volume the whole day, because my ears were just killing me when I walked home afterwards.”

Sarah: “It was an overnight session, too. It must have been in the height of summer because we left at about five in the morning and it was just getting light. And we walked home through Greenwich Park as the sun was coming up and it was just, yeah, a real memory that stuck with me, for that one. It was a great session, wasn’t it?”

Gatha

Sarah: “I mean, it’s quite a spooky kind of track, isn’t it? It’s sort of unsettling. And, even if it really wasn’t intentional for us to make a track that sounded spooky and unsettling, it kind of appealed to us because that was just a bit of a mood we were all feeling at the time.”

Mark: “I was also really into the group, African Head Charge, at that moment, and that track is definitely influenced by them, because I remember listening to them a lot around that time. It wasn’t an intentional [reference] to something like them, but they are definitely coming through in that. Yeah, that slightly tribal dub sound.”

Ruby-Ha

Sarah: “That was a September Sound one, right from the start. All I really remember about doing that was the vocals, and it was done in one of the really nice live rooms, there, with a nice expensive mic. Oh, and also it being suggested to me to do the sort of croaky thing vocal.

"I think I hit upon that by accident, and then someone went, ‘Oh, that sounds nice. Do that again’. Because we were in the nice studio with the nice mic, that would give you confidence as well. I think the mic was a Neumann. We used an SM-58 at home.”

Mark: “I don’t remember much about Ruby-Ha, actually.”

Sarah: “It’s one of those tracks that gets overlooked and forgotten about, really. It was a bit of an afterthought. We never tried playing it live back then, I don’t think. We still haven’t.”

Rupt

Mark: “I don’t remember much about how it started, but I remember just going on and on, mixing it. That’s my memory of it – just mixing it. I don’t mean in the same session. I mean, over four or five different sessions – The same track.”

Daren: “Which mix is this?”

Mark: “It was one of the last mixes, so I don’t know whether that’s purely on the basis of like, we’ve got to stop this now. Looking back now, they all sound the same. I mean the vocals change a bit…”

Sarah: “Yeah. It’s one of the only tracks where I belt it out. I’m giving it a full chest voice rather than the little floaty coos and high notes that I normally do, so it does sound quite different. With the vocals on Succour, it sort of evolved into another thing entirely. On this track there is like a sort of vocalisation thing – just like a little repeating phrase that doesn’t really mean anything in words. It’s different to When Face Was Face, which was sort of little phrases just built up.”

Vex

Sarah: “It’s a heavy one, this. But, by this point we’d had a few years where we were just constantly together, you know? All living and working together. We hadn’t known each other before we came together for the band. So, it wasn’t like we were friends and then formed a band.

"We were kind of work colleagues, you know? So, personality clashes and just not getting on and all that were bound to happen. It was stuff that you don’t really either notice for the first few years, or it just doesn’t seem so important. And by then, I think it’s kind of inevitable…”

Mark: “You get an almost a kind of cabin fever with it. Because it’s like you’re always seeing the same walls all the time, and that is bound to come across in the music.”

Cut

Daren: “Nice bass. Most of the bass was actually sequenced on the album. I think it’s a good bass sound on the album in general, but Mark sequenced it.”

Mark: “Yes. On Cut and Ruby-Ha. The thing about those two tracks is that they don’t exist on DAT, either. With all the other tracks, there are versions of them. There are no other versions of these. I don’t know why that is. Cut is a really good track, too.”

Sarah: “It’s just about my favourite on the album, I think.”

Mark: “It’s one of those tracks that I wish I could mix again. I really do. I think the mix was rushed on that track. I think it could be better.”

Sarah: “The guitar part on this track just makes me go all shivery. It’s just very beautiful.”

Utreat

Mark: “A lot of these little sounds are from Darren’s shortwave radio.”

Daren: “Yes. It’s a radio wave on there. I used that a fair bit. A classy radio wave with some bass. Then Mark, of course, took it on board and started working with Sarah on it, and it came out great.”

Mark: “It’s one of my favourite tracks. The title comes from Utrecht, the city in the Netherlands. We were on tour with the Cocteau Twins, and we were coming to Utrecht, and I wrote the name down in the diary, incorrectly.

"And, as it was such a great place, the name just fit with the track. It’s one of my favourite tracks as it’s nothing like the rest of the album, but it fits in somehow. It’s really quite loose, or kind of feels loose, compared to the other tracks. It has a great atmosphere. Really atmospheric.”

Tempean

Sarah: “This was a hidden track. That was all the rage in those days, as we’d only just recently sort of converted to CDs, you know? I got my first CD player that year. And you started buying them, and then you discover all these little things that you can do with them, like put secret tracks on the end, and stuff. So, yeah, we wanted a bit of that [laughs].”

Mark: “We should have done it like a locked groove at the end – a single loop. It would have worked perfect.”

Sarah: “It also has to be said about this album that there were boxes and boxes of floppy disks.”

Mark: [laughs] “All that stuff was so hopelessly labeled, too. I found some the other day and I have no idea what’s on them. All the titles changed, all the time. You never quite know what a track is, and then you realise it’s actually a track that you did release, but it has a completely different name.”

Seefeel's reissue compilation Rupt + Flex 94-96 is out now on Warp Records.

Future Music is the number one magazine for today's producers. Packed with technique and technology we'll help you make great new music. All-access artist interviews, in-depth gear reviews, essential production tutorials and much more. Every marvellous monthly edition features reliable reviews of the latest and greatest hardware and software technology and techniques, unparalleled advice, in-depth interviews, sensational free samples and so much more to improve the experience and outcome of your music-making.

"At first the tension was unbelievable. Johnny was really cold, Dee Dee was OK but Joey was a sweetheart": The story of the Ramones' recording of Baby I Love You

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track