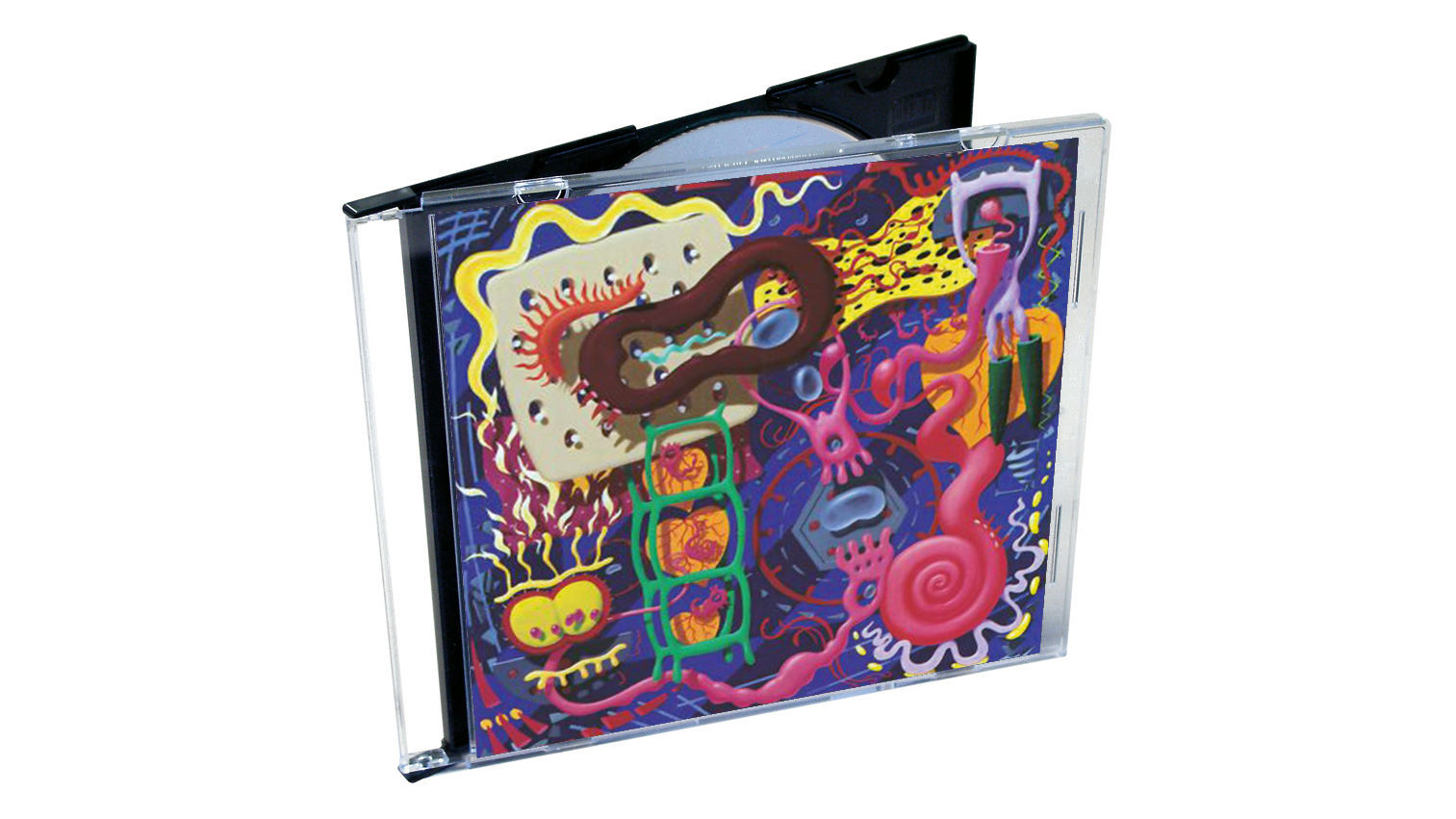

"It was just a pure outpouring of music": Orbital on how they made In Sides

"It was about following your own zeitgeist, rather than anyone else’s, and just doing what you wanted to do"

Picking a favourite Orbital album is like telling one of your children, direct to their cherubic little face, that you prefer their brother because he’s, I dunno… catchier?

In their vast body of cherished, inspiring, and celebrated work, the brothers Hartnoll (Paul ’n’ Phil) have delivered pioneering electronica since day dot. So, when you’ve got one of the iconic duo on a Zoom call, which album do you pick to talk about? Paul?

“I think for me,” he begins, sat in a studio with a surprisingly bad internet connection, “it was a toss up between In Sides and The Brown Album. But, while I love both of them, I think In Sides stands out for me a little bit more because it felt like an album that truly came from the heart.”

Fair play. It did have tracks tackling eco tragedies like Dwr Budr, about a Welsh coastal oil spill (not often a dance music subject, and a poorer scene because of it), and The Girl With The Sun In Her Head – a touching tribute to a lost childhood friend.

Orbital: "Ableton Live does all the things I wanted a sampler to do when I first bought one"

It’s also from the heart in the sense that it doesn’t feel overthought, or bridled by expectations, rules, or steered by the dead hand of an overthinking brain. Loose. More go-with-the-flow, with a go-fuck-yourself mentality. “Yeah,” agrees Paul, once I get him back on the line. “It just kind of spewed out, without really thinking about it. And it was about following your own zeitgeist, rather than anyone else’s. And just doing what you wanted to do. It was just a pure outpouring of music.”

And influences poured in. The jungle beats of the day got a respectful nod, peppered throughout. As did charity shop movie soundtracks from masters like John Barry, Lalo Schifrin, and, of course, Ennio Morricone, which were big inspirations.

“I was just having fun,” chuckles Paul. “Going back through old stuff and film scores. I just couldn’t help it. It was just all very natural, making this album. And that’s why I like it.”

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Fair play. But, let’s cover that Brown Album soon, so as not to hurt its feelings.

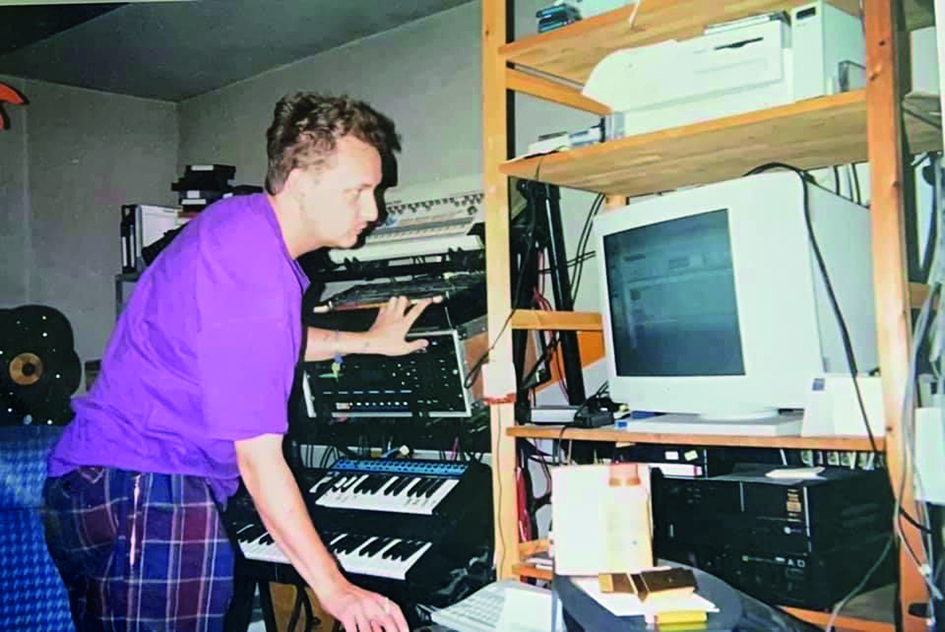

“We made In Sides in Strongroom studios, in Shoreditch. Not in their big rooms, though. It was just recorded in a little room," Paul tells us.

“In terms of kit, and what we used to make In Sides, it was a lot of the [E-mu] Emulator III, to start – not the really posh one, the digital one. It’s like an Emax III, really. There was also a lot of [Roland] 909 going on in there, still. A lot of 808. And then we sampled live drumming from David Gray’s drummer, Clune [Craig McClune].

“There would have still been a bit of the [Roland] R-8 and R-70 drum machines. And there was still a lot of [Roland] SH-101 and SH-09. And then the Oberheim Xpander, big time. Then we used the [Roland] Jupiter-6 and the ARP 2600. Oh, and a [Roland] System 100.

“Yeah, they, I would say, were the main instruments we used. That’s pretty much it, I think. For the main bulk of the heavy lifting on the album, for sure.”

In Sides, track by track with Paul Hartnoll

The Girl With The Sun In Her Head

“This started life as a potential cue for the movie, Hackers. And it didn’t actually end up in the film. We really liked the track, so kept it going. I think it was replaced by a Leftfield track in the end [Open Up]. But, it built up and developed from that, and became what it was.

“It’s kind of named after two things. We recorded it using solar energy only. We had the Greenpeace mobile solar-powered generator, Cyrus, parked outside the Strongroom studio. They came along one Saturday and threw their cables through the window, and we recorded the track with a solar panel. Hence the reference to the sun.

“And then it’s also about a really good friend of ours, one of my old friends from Sevenoaks who I had known since I was kind of 16, called Sally Harding. She was a photographer and she was kind of building up to be the rave photographer of choice. She’d photographed a lot of us around that time, you know? People like us, Reload, Aphex Twin, Spooky. She was doing a lot of stuff for Volume magazine. Yeah, and was just starting to sort of make it, and then you know, unfortunately she died while we were making that track. So, it’s named in part after her, as a tribute, as well.”

P.E.T.R.O.L.

“This was on a PlayStation game [Wipeout]. And it was the first time, as far as I could tell, where just regular music could be in a video game. I mean, on a home console. Everything else had been made on the sound chips. When they came to us, we actually genuinely thought we’re going to have to make this on a special system.

“Interestingly, the first showing of that game, which was a kind of a souped-up version, was in the film Hackers. So, it was another connection to that film. And it was just like scoring a film. I just sat there and I built the track up. It was like, let’s go for speed, let’s go for jungle drums. And that kind of thing. By then it was probably starting to get called ‘drum & bass’.

“But, what I did was get the ARP [2600] and just sent it a trigger, and built a library of sounds onto DAT – percussive and aggressive sounds. So, I got a bit of [Craig McClune] Clune’s drumming, and then just responded with all these samples. And that built up this sort of rhythm bed. And then I wanted something that sounded like racing, so I got the [Oberheim] Xpander and put it on, like infinite, so every note was holding. And then just let it cycle round these droney sounds, for the background. For that kind of slightly racing vibe. But, then with the Xpander, you can pan each voice wherever you want it in the stereo pan. And so I just made this big fat, whining, motorcar/motor racing kind of sound in the background.”

The Box

“I think of this track as two parts. It’s credited as two tracks on some formats of the album. There’s definitely a movement, if you like. But it’s really two distinct parts.

“The first part started as an experiment to do something rhythmical in the vein of Steve Reich. Polyrhythms, basically, where you’ve got patterns cycling around at different rates. And that’s all the bells at the beginning.

“And then it became a kind of slow tribute to, you know, going back to that kind of dulcimer sound, and Ennio Morricone, with the bells, and that kind of thing. And then, while that was finished, I remember going in on a Sunday, and just getting to the end of it and thinking, ‘What happens if you speed it up?’. And then The Box Part Two just spewed out on a Sunday afternoon.

“I remember thinking, ‘Oh, that’s pretty good. I like that. It’s like The Sweeney.’ It felt like a fictitious spy movie theme tune or something more TV, actually. It was like Danger Man or The Prisoner, or something like that. But, it was tied in with a kind

of drum & bass/jungle kind of sensibility as well.

“There was also a video made for this track with ‘The Academy Award-winning actress Tilda Swinton’, as I like to call her [laughs]. Luke [Losey], who has always done our video stuff, knew her and got her in. She was brilliant.”

Dwr Budr

“This track was inspired by a big oil slick that happened on the Pembrokeshire Coast. So, hence why it’s called ‘dirty water’ in Welsh.

“There’s also vocals from Alison Goldfrapp on there, credited as ‘Auntie’. That was something she came up with. I still don’t know why, and I probably don’t really want to know [laughs]. She was kind of going a bit more undercover for us, I think.

“I did this track in one day, too. The day before mastering the album, actually. I just felt like it was a track short. Yeah, it was only an hour and five minutes [laughs]. Yeah, it’s ridiculous, but it was back in the day when the CD was a fairly new format. In the same way that people used to fill up vinyl to the limit, we used to try and fill a CD because it’s like, well, we got a whole CD. Why don’t we fill it? I actually favour the 45 minute album, nowadays.

“In terms of track arrangement I tended to favour A, B, A, you know? You start with something, you go into something, then you come back to what you started with, but make it a bigger version. Yeah. Or, I quite like the Part Two where you do something, and then do a kind of moodier second part…”

Adnan's

“This is the long version of the [War Child] charity track that we did for the HELP album. Basically, the HELP album idea was that everybody had to record their tracks in one day. But, I took that quite literally, in the sense that I decided to write the track in one day, as well as record it. Yeah, that’s kind of what I thought everyone else was doing, in my naivety. I was raised by musical wolves, so I have no idea about things [laughs].

“So, I just started the day by turning on the news, and recording whatever was going on to do with the, you know, Serbia/Bosnia war. And that day when we did it, there was an awful story about a distraught father talking about how his 12-year-old son had been killed by a missile. And so we used a bit of his voice on the beginning of the charity version, talking about his son, Adnan.

“A lot of the percussive sounds and everything were sort of field recordings that were done around a friend’s lockup. And she had some of these industrial pipes. I was banging on the end of them. And then I found that she was planing something. And so I got the portable DAT machine out and put the mic at one end of one of these big pipes, so it just had a beautiful kind of resonance coming through. So a lot of the sounds are from this field recording of our friend Fiona, doing building work.”

Out There Somewhere?

“There was never any intention of this one being 23 minutes long, so it’s another one that has come out in two parts, but I’ve always seen it as one thing. It was literally written in a linear fashion. So, how it starts is how it was written, first. And then the only other intention was ‘Oh, we got an 808 now. Let’s do an electro track!’ So we did that.

“And it started off talking about aliens, and that kind of thing. ‘Is there life out there?’ Very suitable for an electro track. And so it just started to build up into Part One as a kind of electro thing. And then it went into that sort of twinkly System 100 part that happens towards the end of that composition period. It was like ‘Oh, actually, this could be quite nice’. And then it turned into the nice lovely part at the beginning of Part Two, and it became a little bit John Barry and that kind of thing.

“Then you get to a point and say, ‘Okay, I’m bored of this. What about if you play those chords in a different way?’ Then it became kind of quite moody. And then the drums started to develop in a different way. And then, all of a sudden, I found one of my favourite things that I loved about the E-mu Emulator III, which was that you could do velocity to start time. So, I would sort of move through the four-second sample, and it went from minor to major.

“And, all of a sudden, it was like, ‘Woah! The whole track has shifted into a major thing,’ but with the same riff. And that made for a really joyous ending.”

Future Music is the number one magazine for today's producers. Packed with technique and technology we'll help you make great new music. All-access artist interviews, in-depth gear reviews, essential production tutorials and much more. Every marvellous monthly edition features reliable reviews of the latest and greatest hardware and software technology and techniques, unparalleled advice, in-depth interviews, sensational free samples and so much more to improve the experience and outcome of your music-making.

“I’m looking forward to breaking it in on stage”: Mustard will be headlining at Coachella tonight with a very exclusive Native Instruments Maschine MK3, and there’s custom yellow Kontrol S49 MIDI keyboard, too

“Turns out they weigh more than I thought... #tornthisway”: Mark Ronson injures himself trying to move a stage monitor