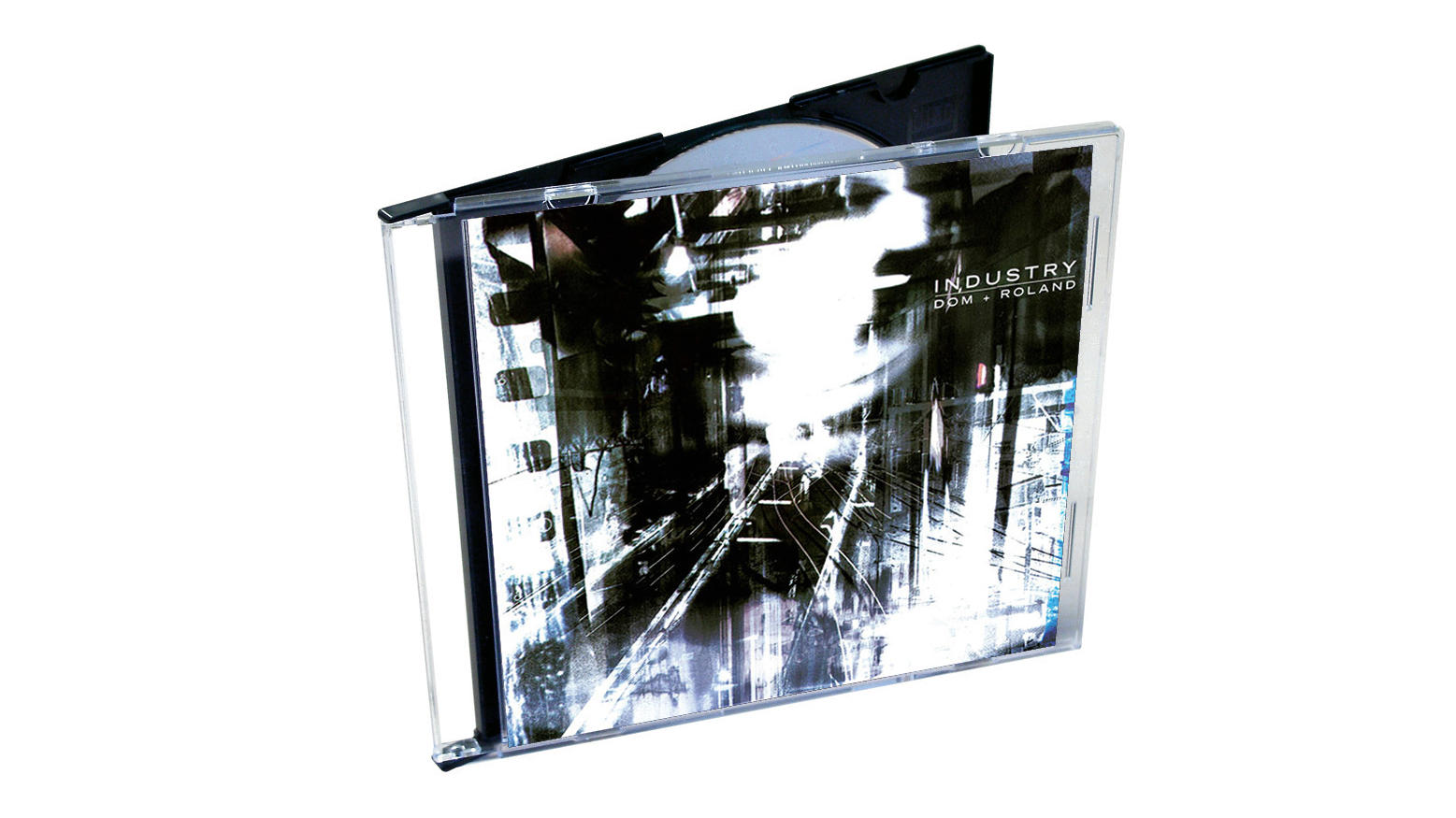

Classic album: Dom & Roland on Industry

Dominic Angas talks us through his 1998 DnB classic track by track

”It’s funny,” begins the normally interview-shy Dominic Angas. “Until recently, I don’t think I’d ever bettered that album.” He’s talking about his debut LP – the iconic, genre-forging masterpiece, Industry.

A collection of super processed, forward-thinking, breakbeat science. A jewel in the legendary Moving Shadow label’s crown. And a body of work that forged its own dark, techy and technical drum & bass path, as the genre was really starting to take giant steps.

Not even in his 20s then, Dom (and the Roland sampler that shared top billing with him), bunkered down and made the album he wanted to hear. “I was young and in that life-changing, tumultuous time, I was just doing it for me,” he says. “I don’t think I write, or wrote music for people, per se. I write because it needs to come out.”

It was a dream of his to join the iconic Moving Shadow drum & bass imprint, known for pushing the creative envelope. And life on the label was good. They allowed him free rein to try what he wanted, leaving him to chop and twist drums and synths, until he had a truly unique sound to his name.

Inspired by dreamlike, high-tech sci-fi films like Blade Runner, he’d spend weeks dreaming up music befitting its neon-lit dystopia. “I was fascinated by these science fiction sounds I’d never heard before,” he says. “And ultimately I was merging that into everything I made. I wanted to create these alien sounds in the studio that no one else had.”

That’s ultimately what music is. It’s just someone taking something that came before and trying to make it their own

When released, his futuristic jungle opus of an LP would help change the scene forever – pushing it in new directions, as other artists took Dom’s baton and ran off with it into the future. “I could name 101 people that have taken my ideas, and they’ve made great careers out of them,” he says. “But, you know, it’s basically what I did too. I think that’s ultimately what music is. It’s just someone taking something that came before and trying to make it their own.”

“I did a lot of the album at the Moving Shadow [label] studios, which was David Bowie’s old writing room.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“Kit-wise I had a Roland S-7600 sampler, obviously, as it’s in my name [laughs]. Then an Atari. Sequential Circuits Pro One, loaded into an E-mu sampler. And I remember buying the very first Yamaha digital mixer – the Yamaha 01. Because I remember a lot of the moves that I did with delay and things were all live on that, with the delay and reverb on a fader.

“And back then, obviously, you’d have your arrangement done. And

then you’d play it, and then you’d have your DAT player recording, and then you’d start doing little moves with the faders to throw a bit of reverb on a snare.

“The benefit of having a digital mixer at that time, when not many other people had them, was that you could actually record these things in as well. So, I suppose that was a big part of sound of that album.”

Industry, track-by-track

Thunder

“It was very inspired by [the legendary Metalheadz DnB club night at the] Blue Note. The whole ‘switching up breaks’ thing. I remember actually all of the breaks in that were put through a grey and very cheap distortion pedal that I bought in Maplin [laughs]. And, for me it was all about having a slightly different distortion sound to everyone else.

“And I also realised that the older the battery that I put in it, the better it sounded. I tried to look for drained batteries to see if I could get a different crunch out of it. Back then it was always about hunting for weird things. Eccentricities like that, to try and get something different to what everyone else is doing.”

Remote View

“I was quite fascinated by the ‘remote viewing program’ that the CIA were doing. The idea that people were being trained to be able to see stuff with their minds. The track really doesn’t say much about it, but I’d found this sample and thought, ‘That’s really cool!’.

“Again, I would have been processing a lot of sounds through external things. I do remember at the time I used to get speakers and put them in different places. And then get a mic, then make a sort of chain, so that I’d play something out of the speaker, and then maybe put a box around it. And then mic it up, and then the box would flap, and then I’d record that flap and then put it back in. There was a lot of really deep sort of sound processing going on here.”

Connected

“Now this is one of those tracks that just came from the idea of trying to create something sort of sci-fi and dark. I just sat there and played around with something until I thought it sounded good. And then I was like, ‘That sounds suitably dark and sci-fi!’. And I don’t know whether I even concentrated that much on making it sound good on the dancefloor.

“I wanted it to be good on the dancefloor…I just more wanted this big and epic sound. I think that’s all I was going for. And I think a lot of the other people at the time were just trying really hard to focus on getting the snare right and the kick right. I was interested in all of that. It just always took a bit of a back seat to me just going, ‘Look at this amazingly big epic thing that I’ve made’.”

Time

“I did that with Matt [aka the producer, Optical] and therefore I think he was much more focused on getting the mix really perfect and sounding good in the club.

“So, I think that one did actually have quite a lot of the right amount of punch to it. But, again it was quite mellow. It wasn’t one of the hardest tracks on the album.

“I think at this time, me and Matt had done quite a few tracks together. We would have used the Sequential Circuits Pro One, loaded into my E-mu sampler. We used ZIP disks and swapped them back and forth. He would have probably come around with a ZIP disk of weird bloops and squelches and stuff that he’d made on his synth, and then that would have gone into my E-mu in my studio and then processed from there.”

Spirit Train

“I remember sampling a Dillinja beat thinking I needed to disguise it somewhat, so he didn’t know that I’d sampled him. I would have processed it. I do a lot of resampling. So, I’d process it and then that could be a layer. And then I might work on a beat for a couple of weeks just to get all these different layers going. And then eventually it would sound slightly different to the original thing.

“It was laborious, but at the same time I didn’t think about it as much because back then music wasn’t so throwaway as it is now.

“We’d put our heart and soul into something, and we do all of these weird processes and spend you know, sometimes a couple of months coming up with these sounds and arrangements. But, the end result was that there would be a record out, and 15,000 people to buy it. So, it would make it worthwhile to be able to put that amount of effort and that amount of creativity into the music.”

Elektra

“This was on that classical music thing of having a pattern that would then repeat with another instrument. I grew up listening to classical. That was something I tried to include a lot. Obviously there’s the light and dark… I’d often do dreamy intros that would lure the listener into this false sense of security, before the hard dark beats would be unleashed on them. And yeah, the contrast between loud and quiet. I was always a big believer in that adage – it’s the sound between the notes that gives it the power.”

“I think actually that track got picked up by the BBC for a TV show called Merseyside Blues, which was about the police. They looped it

quite badly.”

Time Frame

“I was quite pleased with the beat that I made on that. I made that from scratch. I think there was a lot of people making beats from scratch. I mean, lots of people were taking breakbeats, but taking separate kicks and snares and hats from different breakbeats and somehow making a new breakbeat, rather than just taking a break and pitching it down. Or taking a break and replacing the snare – actually trying to make a new breakbeat out of single hits.

“So, for that particular break, it was all about the flicks of the hi-hats. They were quite chunky hats. And I think that would have been quite distorted and resampled through the desk I remember, that break.”

City

“Inspired by the film, The City of Lost Children. It’s a French movie from same guy that did Delicatessen. Really good movie. Very weird and sort of like an alternate reality sort of sci-fi. But, it had really beautiful music and was very beautifully scored. There was a bit in the beginning, with the bit that inspired this track’s intro...

“Often I’d start with a sample and then it would be, you know, a string patch. And then it would be about augmenting that sample and turning it into my own. All samples ended up having to be sort of twisted. That was a big, big part of it. I think I made some of these bass sounds from piano samples, pitched down.”

Chained On Two Sides

“There’s a singer on this. I’d been working with a girl called Shanie, who I’d done a couple of remixes for. And after there were a whole load of vocals leftover from the sessions. I said, ‘Can I put some of these in my tracks?’. She was like, ‘Yeah, sure’. I used her to sort of make my own samples up. I mean, she might have sung something in a completely different context. But, then I just take the words out of context and rearrange them like samples. That seemed to work.

“Also, I think that was the same beat from Spirit Train. I was quite into that beat.”

Anaesthetic

“Again, with Optical. All I remember was that we went to town on the filters on the E-mu. I think I’d literally bought it that day. And we were going through and all these morphing filters that neither of us had heard before. And you could go from one extreme to another. So, the whole tune was all about going with these sort of weird, beat filter extremes, one way to another. And then opening up into a really clean, fat full-range break. And then going back into quarters. It was sort of a journey on a rollercoaster. And that was the sort premise of the track, really.”

Industry

“That was a weird one. I was just sort of let loose, and did my own thing. Obviously people are sticking to certain drum patterns, you know? You have a kick here, and you lay your kicks up together, and your snares up together… But, with Industry I remember thinking it sounded really good when I layered a kick on top of a snare. Yeah. Like, a drummer wouldn’t play that. So I was sort of experimenting with rhythms, I suppose. Layering up kicks and snares. So, you still have the roll of the kick and hats to the snare. But, then you’re marrying them up so that you treat these breakbeats more like percussion, I suppose.”

Kinetic

“I think I’d sampled Blade Runner for this one. Definitely. I remember. And everyone had sampled Blade Runner, and it was just about trying to find bits that people hadn’t used [laughs]. Whether it was stuff pitched down. Or, parts of something that someone hadn’t got to yet. Yeah, so that was that. It was a fun time.”

Future Music is the number one magazine for today's producers. Packed with technique and technology we'll help you make great new music. All-access artist interviews, in-depth gear reviews, essential production tutorials and much more. Every marvellous monthly edition features reliable reviews of the latest and greatest hardware and software technology and techniques, unparalleled advice, in-depth interviews, sensational free samples and so much more to improve the experience and outcome of your music-making.

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track

“Part of a beautiful American tradition”: A music theory expert explains the country roots of Beyoncé’s Texas Hold ‘Em, and why it also owes a debt to the blues