Disco legend Cerrone: “Everyone at the studio was recording a Genesis album and they were looking at me like ‘What the f**k is this guy doing?’”

Calvin Harris may have jested that he created disco, but there’s one man who can legitimately hold up a hand and say he actually did…

Fall silent, for you are in the company of greatness. Marc Cerrone - drummer, producer, artist and DJ - has spent the last 50 years carving his own niche and doing his own thing, all the while influencing tens of thousands of musicians and delighting millions upon millions of music lovers.

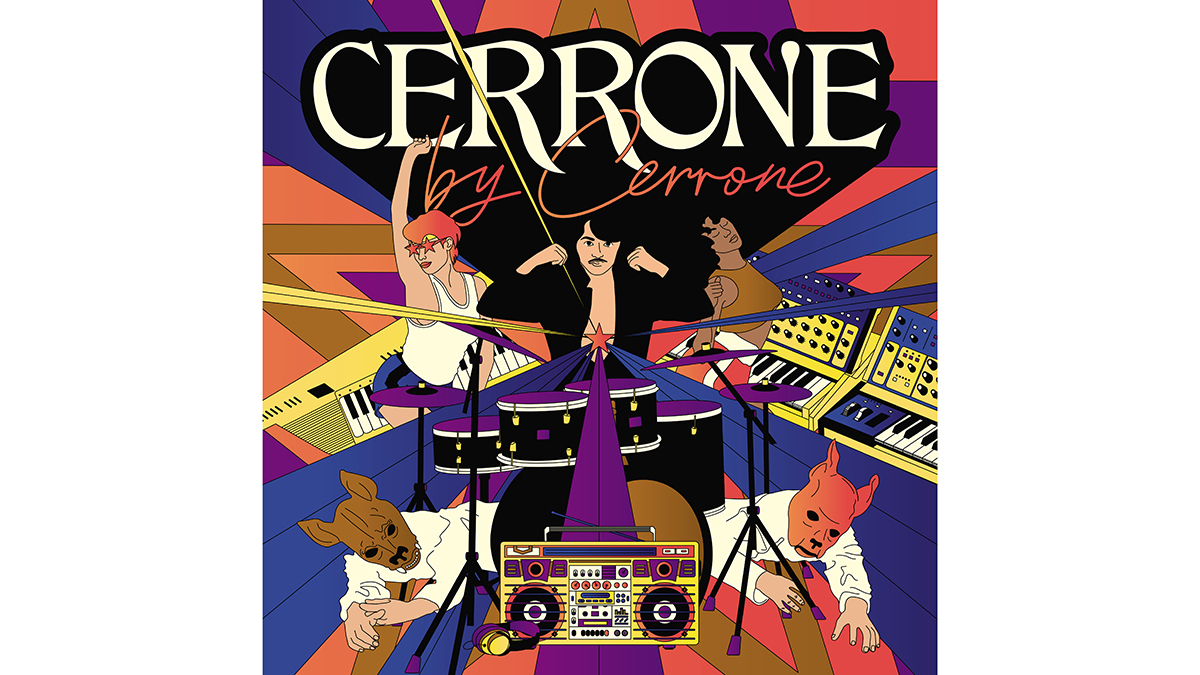

Now, with Cerrone On Cerrone, his brand-new, career-defining album, Cerrone has personally created a seamless journey that reinterprets and merges his catalogue of classics in a whole new way. And with remixes on board from the likes of Joey Negro and Dimitri From Paris, disco has never sounded fresher, more alive, more vital and more ready to - once again - kickstart the creativity of today’s new music makers.

With a view to talking Love In C Minor, Supernature and beyond, we ensnared Cerrone at his studio in Paris to discuss the new album and his new career as an in-demand DJ, and to ask just how one goes about creating a whole new genre of music?

How did Cerrone On Cerrone come about? This is wall-to-wall classic tracks, but it all sounds so fresh.

“I was working on a new LP with original songs but I’ve recently been playing at festivals. Playing to maybe five, seven, 30,000 people. My record company pushed me and convinced me that if I play as a DJ I can play all the big festivals rather than play live. So I’ve kind of stopped my career as a musician. And I’ve been DJing more and more.”

Was it hard becoming a DJ after so long as a musician and producer?

“Ah, but I found the great machine! The Ableton! And with my engineer I started to put samples on my original tracks and soon it was like I was making the album on stage with the public. Then I could go back to the studio and minimise the harmony from certain tracks. Take the original multitrack and work with it. Music is much more minimal these days compared to what it was in the past.”

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

So your DJing influenced the arrangements on the new album?

“Absolutely. The LP is like one hour and one minute of my DJ set. At the big festivals my record company was there and they said ‘Marc, let’s offer this to the public. Let them enjoy this at home!’ I say ‘Oh, you think so? Why not?’. It’s great. I see on YouTube that it’s number one and it’s working very well. We hope that it’s going to push more of the public to come and see me.”

Brendan Reilly is the main vocalist for the album. He’s such a good fit across the songs.

“He was a vocalist with the band Disclosure and I asked him to join me on stage. Sometimes when I DJ I have a bass player, keyboard and electronics and a singer to the front. I asked him to come and he was so perfect. His vocal is so sexy. And that’s not easy because a lot of my stuff was with a female singer. But I decided to have one vocal - one sound of voice for the total piece. And I did that specifically to place some distance between myself and many other producers today.

“Many other producers use incredible vocals but, for me, when they’re finished they sound like the radio or a podcast… They don’t sound like the ‘70s. That’s where I burn. I’m a ‘70s guy! Brendan glues it all together. It’s a great mix.”

Let’s go back to the classics and Love in C Minor. That fantastic original 16-minute version. How does something like that come about? Was it written like that? Orchestrated? Is it a jam?

“Here’s the real story, from the beginning. I was a drummer in a band called Kongas who were really successful at the beginning of the ‘70s. After three or four years I stopped the band. Every year we had 250 concerts… It was too much.

“I decided to quit music. But what I learned when I was with them was that there were two percussionists, left and right, and during the percussion solo I would just… [stomps on the floor as if playing a kick drum]. Just to help them along. So they could show-off, brag, whatever. So I broke up the band, but after a year I started to feel so bad. I realised that I have to do music.

“So I decided to do one more LP - the last of my life. I asked Alec Constandinos, who was the lyricist and writer for Kongas, to join me. He worked with Demis Roussos and Aphrodite’s Child, a lot of good acts. I said ‘I want to do something strange. I want to start with… [stomps on the floor as if playing the kick drum] and… [makes the sound of rattling 16-beat hi-hat and tambourine]’.

“So the first day I arrived at the studio in London and they had these small speakers. The Auratones? I said ‘I’m coming from the stage! Rock and roll! With the big sound!’ So we brought in BIG speakers, left and right, for a big sound, and that first day we recorded only the kick… [stomps on the floor] All day. We got 20 minutes. I had a click on my ear but every minute-30 seconds you lose it a little. So we kept going back… [stomps on the floor] We passed many times. Just the kick in the room. For a pure clean sound. And then we went back and I added the snare, and the hi-hat. So after the first day we have like a drum machine… the drum machine at that time didn’t exist. It was very funny for a drummer!

“Then we put on the bass, and we put on the guitar and I brought some examples by Barry White to arranger Raymond Donnez and said ‘I want to harmonise like Barry White, to have a harmonic sound on the brass’. And he made an incredible arrangement. Then we put on the small vocal melody - ‘Love me, love me’. Everyone at the studio during the day was recording a Genesis album and they were looking at me like ‘What the fuck is this guy doing?!’

“But after a few days we had Love In C Minor sounding like it sounds. Everyone was starting to be interested. I’m a young guy, so I invite everyone to watch me do the mix. And one of the girls that was there, when the music played she was like, ‘Oooh, ooh!’ because the music… it was so sexy! And I said to the engineer, ‘Please, push the red button’. And we recorded her. And after, I asked her ‘Can I keep that?’ And she says ‘Oh, yes!’. It wasn’t planned. I wasn’t thinking. It was just like that.”

It’s such a perfect modern kick drum sound that would be perfectly at home on a record today.

“When you’re a drummer you’re not supposed to be straight. You have to groove to the band, but because Love In C Minor was such a success that gave us a direction. I was surprised by its success. So I was 21 years old and I thought ‘OK. I’ll do a Cerrone LP with the same format’. And that became Cerrone’s Paradise.”

With Supernature the synth was an accident. One day I got an ARP Odyssey at home, and I tried to use it… and fuck! The first thing I heard was the sequencer, and I looked and I thought ‘How do I turn it off?’ I tried, but all I got was the same repeated note! I tried to find it, to change it, but the fucking sequencer never stopped!

At the time that must have been so radical. To play with no swing, no syncopation…

“And within a few weeks Giorgio Moroder arrived with Love To Love You Baby. It was a different BPM, but it was in the same spirit. And from that day a lot of producers started to do the same.”

And how about the fast, arpeggiated keyboard parts of those early disco tunes. Are we still pre-sequencer here?

“The strings and the brass, they were recorded with a lot of musicians. Totally live. With Supernature the synth was an accident. One day I got an ARP Odyssey at home, and I tried to use it… and fuck! The first thing I heard was the sequencer, and I looked and I thought ‘How do I turn it off?’ I tried, but all I got was the same repeated note! I tried to find it, to change it, but the fucking sequencer never stopped! But then I started to hold the notes down, and I thought ‘Hmmm…’ And I thought of a bass part to go with it. I tapped my finger on a microphone for the beat, and I recorded that. I sang a melody over that, and Alain Wisniak [who went on to produce Supernature] said ‘Wow! What is this? Let’s take it to the studio.’

“But when we recorded in the studio we didn’t use the ARP. Instead, we played it. At half speed, each note, layering and working on the sound. Each sound was there because it needs to be there. We took a week to produce the track. And I said to [lyricist and vocalist] Lene Lovich, ‘the lyrics need to be strange’. The way we treat our planet… it’s strange, but it’s our home. I wanted to do something around that. And at that time I’d just seen the movie, The Island of Dr Moreau and I was shocked by that. And this is the idea I gave to Lene Lovich.

“And for the vocal I tried to find someone who was… androgyne? [androgynous] No girl, no man. Just animal. Something like that. And it worked very well.”

Let’s go back to the start. What got you started as a drummer?

“When I was 12 years old I was not a great student. I was always playing drums. The teachers put me out of school. My mother said ‘If you control yourself I’ll buy you a drum kit at the end of the year’. And I thought ‘Why not?’ And from then on, whenever I heard a song on the radio I didn’t hear a song. I heard the drummer. And during the year I learnt to play, for each limb to be independent, and at the end of the year we went to the shop… I started to play. And the guy said ‘Wow. Your son is gonna be a drummer!’

“And I convinced a friend to play the keyboard, and the guitar, and at around 14 years old I started to have a great buzz around Paris. I started to play with different bands until I found a great bass player, great guitarist, and that’s how we became the band Kongas.”

What were your musical influences back then?

“‘70s music was either Deep Purple, Led Zeppelin - the rock sound - or it was pop. I went with rock. Beatles and Rolling Stones? I’m with the Rolling Stones. Beatles are too pop for me.”

It’s unusual for a drummer to be the leader of a band. Usually a drummer is just the guy at the back.

“I don’t know. I find that as a drummer I am the leader. There was one guy, a keyboard player, and he came out in the front. He said ‘Why not?’ And that was Quincy Jones. He was the first musician to come in front and use a singer. So why not?”

As a drummer, what’s your relationship with electronics and machinery? What do you think of drum machines?

“All of my records, my drums, no matter what, after years and years, I play it myself, not program it.”

When you first created the disco sound, did you know that you had a hit on your hands?

“The way I made it, I thought that it was never going to be released. This was just for me. And the record companies said: ‘Number one: 16-and-a-half minutes? We can’t release this. And number two: why are the drums so loud!?’

“But we need to hear music for the night, and dancing. It’s not for what we hear on the radio. I tried to explain but nobody understood. I’m a drummer! If I was a sax player there’d be sax everywhere! Nobody understood me. But the reaction in the discotheque in Paris? It was “Wow… wow!”

So you had to release Love In C Minor yourself?

“A friend of mine convinced me to press a few vinyls. I thought ‘I have nothing to lose’. At Island Music in London they told me they could press it for me but the minimum run would be 5,000. I thought ‘Ohh… 5000?’ But we made it, and I started to give it to some shops, not just the clubs. Five here… three there…

“And one of the distributors I sent my record to, he was buying records from America - records by Barry White - and he had records to return to New York, but he sent my records back there by mistake. And when Love in C Minor started to be played in the club in New York the buzz was so big that one guy - Frankie Crocker, the radio DJ - when he played the record he wanted to know more. He said ‘Call us. Tell us. Who is Cerrone?’ He thought it was a big producer who’d changed their name. And they tried to find me in London because a London address was printed on the back of the sleeve. But nobody could find me.

“So Frankie Crocker calls Neil Bogart, the boss of Casablanca records, and they decide to make a cover! The name of the band was The Heart and Soul Orchestra. The track was the same… but it was not the same! And that cover version got in the top ten so I heard that in France. I went to New York, Atlantic Records, and I told them ‘I’m the one! THIS is the original’, blah, blah blah. And I signed to Atlantic and Ahmet Ertegun, the boss of Atlantic, took me in and showed me the business. For seven years I learned the maximum from him.”

Of course, I got my place at Studio 54, and I spent a lot of nights there. Don’t ask me to give you details. But I was there.

Being signed to Atlantic in New York, you must have visited Studio 54?

“We hear that, in New York, a theatre is going to be transformed into a club. And that was Studio 54 and, of course, I got my place there, and I spent a lot of nights there. Don’t ask me to give you details. But I was there.

“I remember the owner put all the actors and singers and special guests in the VIP area. It was very special. And when Supernature arrived in ‘77, ‘78 that put me at another level.”

Was there a lot of rivalry between the disco producers at the time. Yourself? Giorgio Moroder? Patrick Crowley?

“I never met Patrick. And I only met Giorgio five years ago. I met Donna Summer a lot of times. We’d always meet backstage for awards and TV shows, but never Giorgio.”

And when disco broke big, did that feel like vindication? How was that for you?

“That wasn’t us. Giorgio, Nile Rodgers, Earth Wind and Fire, Kool and The Gang, myself - we were the original. Instead people at the time said ‘This is disco shit’ because it was just a pop song. Record companies all around the world pushed all their artists to record their new single in a disco style. No.”

So something like Saturday Night Fever?

“It was not disco. But it was brilliant. It has what disco has - the atmosphere. And what the Bee Gees created with each song - incredible atmosphere. But I don’t like to hear the pop with the disco. Now, the Rolling Stones with Miss You - they made disco? And Rod Stewart with Do Ya Think I’m Sexy - he made disco? But is it just because you have the strings and put the kick drum on every beat? No.”

So what is the disco sound? If a record is going to be a disco, what does it need?

“There is no concept. I just put everything I like into it. Brass, strings, percussion. Why I had this idea - as a drummer - to make this kind of thing? [shrugs shoulders]. Giorgio [Moroder] made me start to like the pop with the disco. The way he worked with Donna Summer, he was an incredible producer.

“But as Rolling Stone magazine in the States said, the real disco - the disco for the body, the music that creates the atmosphere - it’s built like a pyramid. First you have the bass of Giorgio, and then the rhythm track and the kick of Cerrone, and then you have the guitar of Nile Rodgers. That’s la fondamentale!”

So how do you find DJing versus playing live these days?

“It’s the same. But as a DJ you’re by yourself. You’re in the middle. If something happens, you’re fucked! But the way I’ve made it, working with Ableton on stage, it’s just the same.

“When I DJ I’m the one that plays the most vocals on the set. Some DJs are totally instrumental. Even when I started out I always wanted to get my sound. Seriously. I never wanted to sound like someone else. It was never my goal to make a hit. Make a club smash, yes, but never ‘a hit’.”

Like the Summer Lovin’ single? With Purple Disco Machine?

“He came to me last year to clear a sample from an old track. I think ‘Who is Purple Disco Machine?’ So I checked on the web and Spotify and he’s like 300, 400 million plays! I start to listen and he’s brilliant. He’s one of the artists who gets the heritage - the real disco heritage. He asked me for the clearance - he wanted to use the bridge of my song Got To Have Lovin’, which isn’t so well known - and I liked his track so much I said ‘Here, here’s the multitrack. Use it!’ And you know what? He added this bass… oh! It was so good. Why did I not do that myself? And he sent it to me and I said ‘Now I want to do the drums! Let me redo the drums.’ So I did the drums and I sent it back. We went back and forth and we made the track and it’s real, real disco. It’s charted everywhere now.”

It’s great to see that dance music is still so alive and evolving today.

“You know what? I’ve passed 50 years on stage now and the attitude of the people dancing now? I see the young people and their attitude. It’s not like the 1980s or the 1990s. Of course, the people danced back then, but it’s not like today. When I’m on the stage and I’m close to the people… it’s good to find something, somewhere, that, just for a few moments… it’s all good!

“The people, they say ‘We are your future, Cerrone!; This is why, at my age, that I love to be on stage. Right now I’m at home and I’m happy. But in two weeks I go back. I can’t wait! It’s my life.”

Daniel Griffiths is a veteran journalist who has worked on some of the biggest entertainment, tech and home brands in the world. He's interviewed countless big names, and covered countless new releases in the fields of music, videogames, movies, tech, gadgets, home improvement, self build, interiors and garden design. He’s the ex-Editor of Future Music and ex-Group Editor-in-Chief of Electronic Musician, Guitarist, Guitar World, Computer Music and more. He renovates property and writes for MusicRadar.com.