"Plugins help you get ideas out quickly. By the time you’ve patched a hardware synth, found the right cable, turned it on and tuned it – you’ve lost the idea": Catching Flies

Manipulating samples into abstract new forms, Catching Flies has emerged with a creative identity all of his own. We sat down with the producer to find out more about his latest release, Tides

Learning his craft at the age of 16, before going on to gain recognition for his sample-based flights of musical discovery, Catching Flies – aka George King – is positively giddy at the prospect of his latest record, Tides being released.

This second album is a hook-laden, aural labyrinth, dense with evolving textures and liquid beds, assembled from often entirely unfamiliar starting points.

We spoke to George to learn more about the making of this album, a follow-up to 2019’s Silver Linings, and his approach to music-making in general. First of all, we wanted to know where George starts on a practical level when sitting down at his home studio desk.

“I think in terms of hooks. I love making instrumental music. I grew up listening to instrumental jazz and trip-hop in its golden era. Records like Cold Water Music by Aim were big influences. The mixture of that and admiring pop and catchy music is that you try and create these vocal hooks but you end up doing it with instruments.”

Created in George’s home studio, the album’s development was in sync with the rhythms of his domestic life. George would often leave the studio to ponder the record’s themes further.

“I spent a lot of time in nature writing it. I got into going to a different seaside town every Monday. I wanted to refresh my creative process. Although I do a lot of work in my studio, it can be nice to be sort of ‘shocked out’ of that environment and be somewhere totally different. I find writing while I’m touring to be helpful. Not for getting complex arrangements down but just logging those initial ideas.”

Tides had no contrived ‘starting point’, instead evolving naturally from King’s experimentation. “I’m always trying to push it into places where it wouldn’t necessarily belong. With sampling, a lot of the records I get are from charity shops. I love it when, say, I’m listening to a whole record of ’70s prog rock, and I find one isolated harp note. I can take that and completely remove it from its context. I’ll try and give it a new setting.”

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

George and Paul

George’s sampling process is rooted in very precise organisation. “Generally what I do with samples – whether they’re from a record, from YouTube or from something I’ve recorded myself while I’m out and about, is that I catalogue it all by what it is. I have sample folders called things like ‘2023 – Guitars’ and then there’ll be a load of guitars. Kalimba – same thing. Therefore it means that when I’m in the zone, making music, and feel like a track needs a kalimba, I can quickly bring up a load of samples. I’m able to find things easily.”

The next job is to detach them from their original context as much as possible. “I’ll manipulate them and play with them – taking them out of their form. A lot of the stuff you hear on the record might have evolved really far beyond what it was originally. So, it might be a harp sample but the end result doesn’t sound like a harp. It sounds like an ambient drone.”

If I find a sample that I really like, then the possibilities are infinite in terms of where it can go

George’s DAW of choice, Logic, has several useful tools for this purpose, namely Flex Pitch and Flex Time. But, a real secret weapon is an open-source sound transformation plugin called PaulXStretch. “It extends sounds. So, if you put a 30-second recording of a harp in there, it will extend it for an hour. It won’t mess with any of the transients within it, so it doesn’t sound terrible, it sounds like a really beautiful, long piece of drone. Sometimes I’ll put something into that, then put it back into Logic and go through it and find little bits that work. Elements where the harmony becomes interesting.”

The colourful Halo and the instrumentally dense title track are cited as a couple of tracks that took longer to get right than most. “The title track, Tides, was the one that took the most iterations. I find a lot of the time that music goes through a lot of different versions. If I find a sample that I really like, then the possibilities are infinite in terms of where it can go. So, sometimes I’ll just do a very quick ‘throwing stuff at the wall’ arrangement where I try out different chord progressions and moods until I find something that makes sense,” George says.

“If I find a bit of sound that I love and is really interesting to me, then I take a lot of time going round the houses to find the one thing that sits right with me. Ultimately I want to do that sound justice. So, generally speaking, all the tracks go through a lot of different versions. Some less so than others, for example, the track Friday Lake was a pretty quick one”.

If I find a bit of sound that I love and is really interesting to me, then I take a lot of time going round the houses to find the one thing that sits right with me. Ultimately I want to do that sound justice

George points to the blissful Snow Day as his favourite piece on the record, “In terms of composition, Snow Day felt like the biggest departure from what I’d done before. It’s a three-and-a-half-minute piece of music that goes through various different stages and journeys. Musically it’s a fair bit more complex than what I’m used to doing, with the string section and lots of evolving elements.”

Another key tool deployed by George when making Tides was Celemony’s Melodyne, which was used to change the pitch of individual samples. “[With Melodyne] I can put something in there, then change the notes that are playing to make it fit the composition I’m making. Generally, a lot of the time I’m chopping stuff and reversing stuff. Reverse might seem like a very obvious tool but I use it all the time. It’s an instantaneous way to get very different results.”

Musical mistakes

Despite previously working in a rented studio, George now works exclusively from home. “I use solely my home studio. That’s out of choice – I did have a studio out of the house for a while but for me the creative process is so entwined in everyday life. It makes sense for me to work on a song for a couple of hours, then put a wash on, then maybe go for a walk around the park. That really informs the music. It’s a very naturally evolving, organic process.”

George continues, “When you rent high-end studios they don’t have natural light because of the sound-proofing. Natural light is really important because a lot of my music is based in nature and the real world. It makes sense for me to be making it in one of those settings. I also found that going to a studio every day put a lot of pressure on it, because I felt like I was going to work and I had to make something good. This way round I can kind of dabble with stuff and if it’s not working I can go and do something else.”

The freedom to make mistakes is also a crucial consideration. “I’ve had the privilege of using some big studios with engineers, shiny preamps, and big desks. At that point, my imposter syndrome kicks in. I tend to work best when I’m completely alone and have the scope to mess around and make mistakes.”

Mistakes are, in fact, behind most of the album’s key moments. “The most interesting moments came completely from mistakes. For example, I’ll have something looping in Logic then I’ll open something by accident and hit upon an interesting juxtaposition. Without trying to ruin the magic, a lot of this is down to chance, trying things out and experimenting.”

Orchestral growth

A key aural component of this record is the ornate and often sweeping string ornamentation, provided by string arranger Thomas Lea. We wonder what prompted George to seek him out?

“What I find interesting about strings is that they’re the only thing aside from the human voice that can bring that range of emotion to the music for me. Strings have a similar frequency and emotional range as the human voice. With Tom, the way I worked it is that I would hash out some very rough string parts on a MIDI instrument to give him an idea of where I thought he would go, and he would then flesh that out.”

Thomas, working by himself, built up orchestral textures that emphasise and enhance the record’s most affecting moments. “He does it all himself, so he can create what sounds like a quartet with just him and his studio, layering the parts painstakingly. You get that illusion of depth in the music.

“That was one of the overarching themes of the album in terms of how I approached it. I wanted to have that illusion of depth – that it was much bigger than me on my own in the studio with a MIDI keyboard. Tom’s a genius, he really understood my sound and what I was trying to achieve. Generally when you work with people you tend to have a lot of back and forth. But he just sent back what he’d done and it sounded amazing to my ears.”

For me, drums serve a much more supporting role, and often I just want them to complement what’s going on melodically

George tells us that the original decision to bring more strings into his work started with an extraordinary live performance at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. “[It was organised] via Cercle, they’re an online electronic music brand. They approached me and said ‘we’ve got an opportunity to film at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris and do you want to write a track for it?’

“I went to Paris and spent a day or two there, walking around and taking stuff in. I wanted to write something that felt quite grand. That’s where the string element came in. It felt like I was taking the electronic music side of things and adding something that represented the museum’s status and grandeur. That really kickstarted the album-writing process, I loved that idea of merging two worlds that generally don’t go together.”

With all of this focus on the musical information, we ask George at what point beats and rhythms become a concern. It transpires that they’re usually a later addition, “My focus has been on melodies and the emotional content of those melodies. Making that all sound like I want it to before I get stuck in with drum programming. For me, drums serve a much more supporting role, and often I just want them to complement what’s going on melodically.”

It’s interesting to hear this, seeing as George’s way into music production was via his early forays into jazz drumming, but he explains to us that, “In jazz, a lot of the rhythms mimic what the melody and music is doing, so you’ll have little ghost notes on the snare that hit when the melody hits. Generally speaking I build the drums around the melodies so I sort of fill out the gaps where the melody isn’t doing its thing.”

Catching the wave

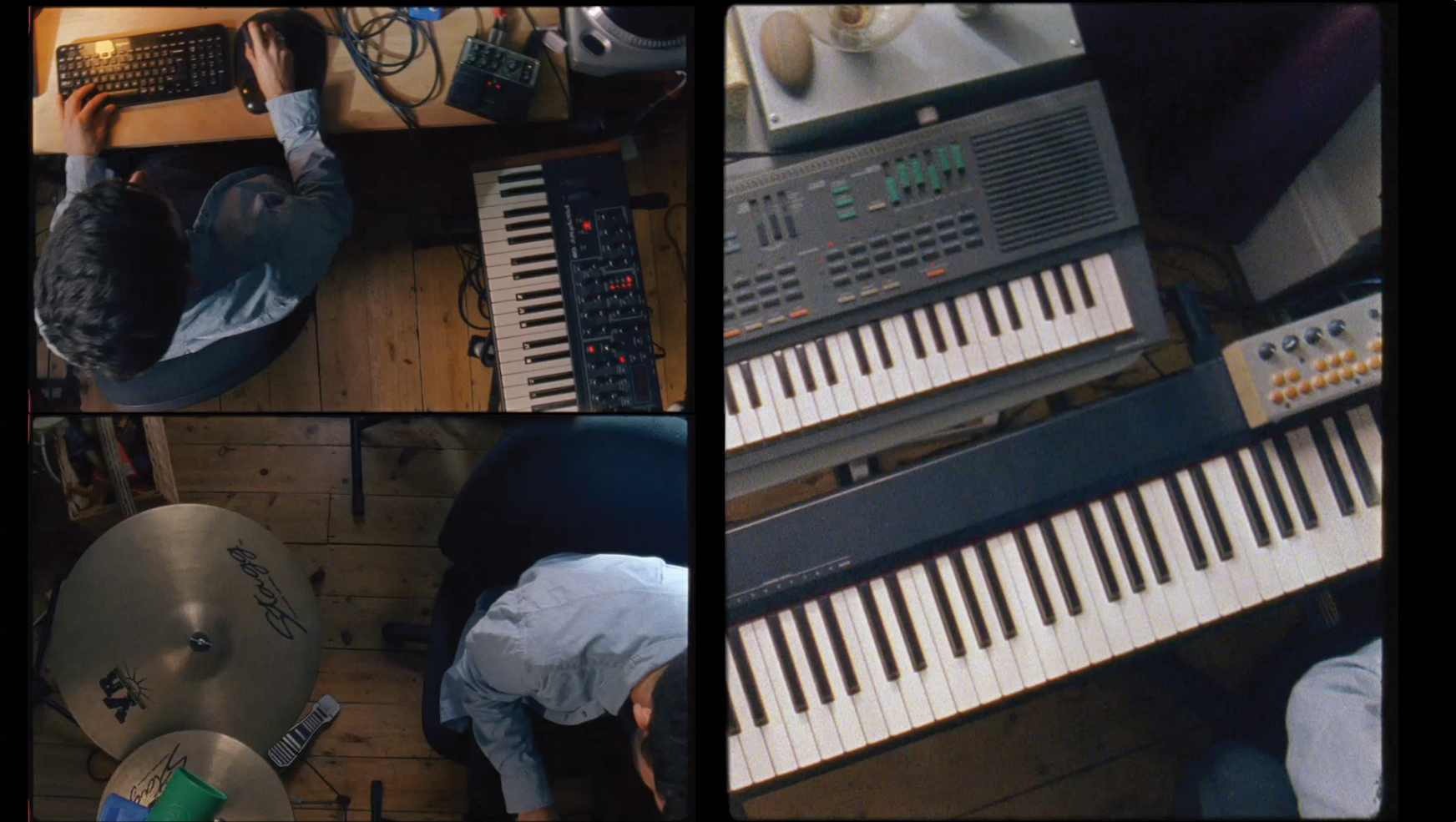

For most of the making of Tides, George remained in-the-box, but he’s keen to mention some hardware beauties, sitting defiantly in his studio. “I’ve got a Dave Smith Prophet 08 and a Nord Lead and various other hardware tools. In reality though, the thing that’s most beneficial for me is to get my ideas out really quickly and instantly, and I find that much easier to achieve with plugins. By the time you’ve patched the [hardware] synth, found the right cable, turned it on and tuned it – you’ve lost the idea.”

George refers to an idea he recalls Brian Eno talking about, which likens the process to surfing: “His analogy was basically that you sit on the water on a surfboard for ages, waiting for a wave. Then that wave comes, and you have to do everything in your power to ride that wave for as long as possible for it all to fall out. You need to create an environment where you’re able to do that and it becomes easier. In terms of my process, if I’m half-way through an idea and I need to find a cable to plug my synth in and patch the MIDI up, then I lose the flow.”

Despite being a computer musician through-and-through, George often feels the need to add a touch of reality to his sonics, “What I find myself doing a lot is spending time trying to make it sound like it’s not from the computer. Whether that’s layering it with foley, or pitch-shifting it dramatically to make it sound old and crusty. Giving it a bit more life. I find that when sound travels from out of the computer into something else and then back in again. A lot of the time, I run the music out, through a guitar pedal, then back in through the computer. Through that process, you get more interesting results.”

In the Catching Flies workflow, the speed factor is crucial – and inspiration can strike at any point in the day. “I get inspiration all the time. I’ve got into the habit – especially with this record – of recording ideas as they come. I might be walking down the street and I’ll have an idea for a melody. I’ll do a recording into my phone as a voice note. I’ll come back to it at a later date. I’ve got hundreds of melody ideas that are sitting there. When I’m living my life and not in the studio, I solve problems. Sometimes I’ll be halfway through a track and hit a brick wall and won’t know where to go next. So I’ll go for a swim and I’ll suddenly have a flash.

I’d say all the best ideas I’ve had are not ideas that have come from sitting down and thinking, ‘I want to write this type of thing’

"I’ll think ‘Ah, that’s what I need to do!’. I’ll come back and it’ll all make perfect sense. But when you’re in front of a screen and endlessly trying, it sometimes doesn’t happen. I’d say all the best ideas I’ve had are not ideas that have come from sitting down and thinking, ‘I want to write this type of thing’. It’s been from not having a planned studio day and messing around with something for half an hour, with no pressure or intention.”

While other artists might pore over their streaming stats and sales analytically, trying to determine the ‘perfect’ formula to guarantee success, for George, music leads the way. “I’m quite old-school in that sense. I’m a bit of a luddite when it comes to social media. I don’t find it beneficial to me in any way – in terms of productivity and otherwise. I’m always being told that I need to do more on it. I prefer to spend my time working on the music itself. For me, it’s much more important to focus on the reason I do this in the first place, which is the music. Then, anything that follows is a bonus. I’d make music if nobody was listening. It’s something I have to do.”

I'm the Music-Making Editor of MusicRadar, and I am keen to explore the stories that affect all music-makers - whether they're just starting or are at an advanced level. I write, commission and edit content around the wider world of music creation, as well as penning deep-dives into the essentials of production, genre and theory. As the former editor of Computer Music, I aim to bring the same knowledge and experience that underpinned that magazine to the editorial I write, but I'm very eager to engage with new and emerging writers to cover the topics that resonate with them. My career has included editing MusicTech magazine and website, consulting on SEO/editorial practice and writing about music-making and listening for titles such as NME, Classic Pop, Audio Media International, Guitar.com and Uncut. When I'm not writing about music, I'm making it. I release tracks under the name ALP.

"I said, “What’s that?” and they said, “It’s what Quincy Jones and Bruce Swedien use on all the Michael Jackson records": Steve Levine reminisces on 50 years in the industry and where it’s heading next

“I’m looking forward to breaking it in on stage”: Mustard will be headlining at Coachella tonight with a very exclusive Native Instruments Maschine MK3, and there’s custom yellow Kontrol S49 MIDI keyboard, too