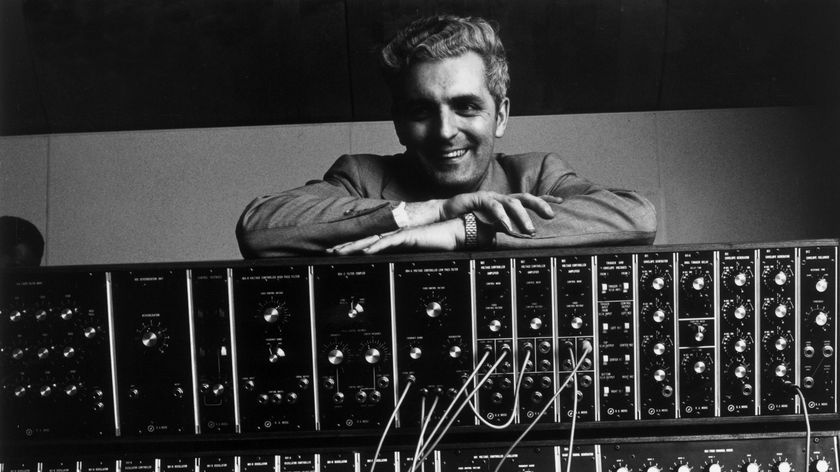

"There’s no bigger turn-off than going into a studio that feels like a spaceship, with a massive chair and loads of posh gear that you don’t want to touch": Bullion on designing a "homely and welcoming" studio space

We visit producer and songwriter Nathan Jenkins in the studio to talk self-doubt, eBay bidding wars and the joys of the laptop mic

Success offers little protection from self-doubt. Nathan Jenkins - better known as Bullion - has produced for Carly Rae Jepsen and Ben Howard and earned both critical renown and a considerable following as a solo artist, but continues to struggle with a question that has surely plagued many readers of this website: is the music he makes actually any good?

“That’s the biggest hurdle to get over with anything I make,” Jenkins tells us. “But in the end, it’s not any of my business, and that’s liberating”. It is emphatically our business, though, and we’re happy to declare ourselves big fans of his latest project. Featuring contributions from Panda Bear, Charlotte Adigéry and the aforementioned Carly Rae, Affection is a pop record at heart, albeit one executed with artful subtlety.

Where Jenkins’ early work explored ingenious mashups and leftfield club excursions, his recent output prizes clarity over clamour, a skilful touch in the studio rendering each sound with remarkable lucidity. Though bright and playful, Jenkins’ cryptic lyrics and staccato synths harbour a melancholy undertone, conjuring a crisp and sophisticated vision of alt-pop.

We visited Jenkins in his London-based studio space to find out more about how the record was made.

Let’s begin by talking about your introduction to music-making. When did you start experimenting and what kind of set-up were you working with at first?

“I was given a four-track by a friend of the family. I wanted to emulate the corny guitar music I liked as a kid, playing along to cassettes and making recordings. My Dad was an early adopter of Apple Macs, so I found out about Logic and started making music on the computer.

“I abandoned the guitar for a while, after realising the possibilities were endless - I nearly sold my Strat to buy more software but my parents wouldn’t let it go and they were right not to - I love using guitars on nearly everything I make.”

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

How quickly did you begin to hone in on a style and sound that felt like your own?

“I’m still in the process of figuring that out. It’s not for me to say, I’m too close to even understand what that sound is. It took a long time to make anything I was happy with, probably not until I was in my early twenties, making beat-driven tracks inspired by 2-step garage. I went to a night called CDR at Plastic People, when it existed. You’d hand in a track you’d made and they’d play it on the sound system. Mine sounded terrible and the person next to me told me as much, without knowing it was my track. I took things more seriously after that!”

What kind of setup were you working with back then?

“It was an old Mac tower, using Logic 6 or 7. I was still trying to work out how to do quite basic things at that point. There’s probably some naive things I did that I wouldn’t do now. I wish I could undo some of my learning and I try to keep that in mind, not get bogged down in what I should be doing.

“Working with people who are new to things, like songwriting or singing, there’s always things that happen in those early recordings that don’t happen once you’ve gone a bit further and you forget how to be naive and in the moment.”

I suppose you can get too entrenched in established ways of working…

“Yeah. Also on a technical level, the more equipment you accumulate, the more likely you are to get hums and lose time fixing things. Early on, it was a very minimal set-up, and I had no concerns about needing to stand in the exact right place in my room to avoid noisy guitar pickups.”

When did you begin working on the tracks that would become Affection?

“With all my solo stuff, it’s quite a long process, with tracks going through various stages. Usually over at least two years. I can’t think of anything I’ve finished that was less than a two-year chipping away process. It’s the illusion of something that happens more organically, but it’s laborious work.

“You think you’re onto something and then you realise you don’t like it. Then another stage of thinking this is an improvement, then wondering if there’s something better beyond. I’ve surrendered to the fact that it’s how I get music finished. I wish I could be someone who knocks things together quickly without the pain, but it’s not realistic and probably keeps me moving forward.”

Is self-doubt something you’ve struggled with creatively?

“It’s number one. That’s the biggest hurdle to get over with anything I make: is it any good? In the end, it’s not any of my business, and that’s liberating. Again, it’s just about surrendering to whatever feels the most finished and trying not to second-guess along the way. Saying that, I think second-guessing can be useful to get to the next stage. There’s no singular approach, but self-doubt is always part of it.”

Have you developed any strategies over the years to overcome that?

“Deadlines - that’s the best way to finish things. It’s practical. There’s nothing you can do beyond this moment. The easiest way to finish, other than that, is Brian Eno’s whole thing about how beyond a certain point, you’re not improving it, just changing it. I try to keep that in mind, but then who knows where the threshold is to judge that!

There’s self-doubt even in what I’m saying to you right now. There are no firm answers on any of it

“There’s self-doubt even in what I’m saying to you right now. There are no firm answers on any of it. Leaving things and coming back to them is useful, if time allows.”

Talk us through your studio space. What were you trying to achieve with your set-up?

“My Dad’s always worked from home as a designer and his study is what I based my studio on. More of a homely and welcoming space than a 'studio' studio; an appealing place to be and have ideas, with records and books and things hanging on the wall. For me, there’s no bigger turn-off than going into a room that feels like a spaceship with a massive chair and loads of posh gear that you don’t want to touch. I only want to have things that are being used and kept in workable condition.

“I try to really take care of the space, and all the equipment in there is something that I’ve bought specifically because I’ve used it elsewhere and I know it’s going to be used in my room, or things that I’ve bought and sold and bought again because I missed what they did. For now, it feels permanent, but who knows, in a few months I might feel differently.

“What I used to do is buy things for a project and then sell them at the end of it. It was a strict one-in-one-out scenario to not get too clogged up, because that destroys creativity for me. Having too many nice things to play with, it’s too much.”

Could you talk us through a few pieces of equipment - synths, effects, instruments - that were fundamental to the making of the new project?

“It’s funny because it’s taken a few years to make that record, I’ve bought and sold quite a few synths and drum machines along the way. I got really obsessed with this Vermona drum machine after I lost an eBay bid for it by 20 euros or something, when I was living in Lisbon. I got it into my head that if I don’t have that drum machine, whatever I make next is not going to be very good.

“It was a DRM, from 1987. This grey, chunky-looking thing with orange and black buttons. I’d heard a demo that sounded great and thought, that’s what I want my next record to sound like. Genuinely, I stopped making music for a bit when I lost the bid. I can be a bit obsessive about those things.

Genuinely, I stopped making music for a bit when I lost the bid. I can be a bit obsessive about those things

“When I eventually did find another one, I paid slightly over the odds for it, made a couple tracks and then sold it. The myth of this machine overcame the reality - It sounds great for a certain thing, then you try it on something else and it doesn’t work. Then you’re like, okay, this isn’t it, I need something else. So I learned nothing from that experience, other than to win the bid the first time round at the cheaper rate. [laughs]”

Does anything else come to mind?

“It’s more about the people playing on the album than what was used. That’s one of the discoveries I’ve had with studio gear and collaboration; if an interesting musician comes in and plays a synth that you were falling out of love with, they might play something that makes it sound incredible. Same with a drum machine; hearing someone else program a certain beat with it might change my whole feeling about it.

“Meeting Jay Flew, a multi-instrumentalist and songwriter, very late in the process of making the album, opened up a lot of new avenues for songwriting in particular.”

Which tracks did he contribute to?

“The Flooding. I made that song playing parts in one-by-one, but I got stuck. He came in and learned all the chords on the guitar quite quickly and played it through in the room as a whole song, then we rearranged it. I’ve been working with him regularly since, he’s a great musician and writer - I learn something new every time.”

Do you think that comes from your background in electronic music, that programmatic approach?

“Absolutely, and not really being a well-practiced player. Working with someone like that who can play so well and interpret an electronically-built track into a more performed piece was exciting. My background is using samples and programming to make songs. The limitations of pitching samples to make chord changes and progressions probably shaped how I think about making music, so it’s good to challenge that.”

Are there any samples on the new record?

“World_train is based around a looped passage from a Kevin Ayers track. It’s a hoedown sort of thing. I’m sampling less in my own work and I prefer to use samples more as decoration than the foundation of a song, but this loop was so fun to sing over.

I’m pretty fussy about synth sounds, but they don’t have to be analogue

“It's partly from a practical point of view: clearing samples is expensive and replaying them often falls flat. Bringing musicians in is a form of sampling, in a way - getting people to play something interesting that you could imagine hearing on someone else’s work, then bringing that into the music. It’s sample-free sampling. [laughs]”

Synths are clearly a central aspect of your sound. Which synths did you lean on the most in the new project?

“I had a Prophet VS for a while, that was really fun to use. I’ve had a few Sequential synths. I had a Prophet-5 and a 6 and then the VS. I’ve been using the Groove Synthesis Third Wave for a while now too. I think people from Sequential made that, so I must be drawn to whatever it is in that sound.

“It’s a mixture of digital and analogue. A Waldorf Microwave, a Roland JV-1010 that I got in Lisbon. There’s probably a bit of that on the album. I’m pretty fussy about synth sounds, but they don’t have to be analogue.

“Synths with built-in effects can be pretty fun, especially when you’re scrolling through presets. Doing that as someone’s playing, you get all these effects cutting off as you change preset, coming to a dead stop and then a delay kicking in… those Roland ones are great for that.”

Are you someone that likes to design patches from the ground up or more of a preset-tweaker?

“Somewhere between the two. I haven’t got the patience for modular synthesis. It’s insane to me, I can’t spend the time sitting in front of that wall of twiddling. I like having a bit of that work done previously. It’s all about how the thing sounds as someone’s playing it, because just scrolling through presets and hitting one note doesn’t really give you an impression of what a patch is going to sound like in a song. It depends on the time you’ve got, and how crucial that part is to the track. It’s all got to serve the song. It’s about how everything interacts.”

Do you have any go-to pieces of outboard for recording and processing synths?

“The Moog MF-104M is excellent. If it’s sync’d to the track tempo, when you change the interval of the delays you get a pitch-y effect that’s often in key somehow. I don’t exactly know how that works - maybe I’ve just been lucky every time, but it’s such a musical thing.”

Is that an OTO BAM on your desk too?

“Yeah, the freeze function on that is fun. Any FX unit with a freeze function is very appealing. Making drone-y things that you can pitch, creating frozen chords… anything that’s a single held chord. There’s some Celtic instinct in me to go towards a sustained drone.”

When it comes to plugins, could you talk us through a few that you found yourself using the most on the new record?

“A lot of Logic stock plugins. They do the trick. I’ve been drawn in by posh effects at times, but generally, because I’ve used those Logic plugins from the start, I know them pretty well. It’s nothing extraordinary. Soundtoys is great. Another thing I obsessed over is the Lexicon Prime Time 93, that the Soundtoys PrimalTap plugin is based on. I very nearly bought one of those, but the maintenance is hell apparently. That also has a freeze function…”

Have you experimented with any new techniques on this project?

“The one-in, one-out approach, it’s something I’ve applied to my production as well. If I’m recording a part of a song, I’ll try to take something else out or make space for that new thing. I’ve been a maximalist in the past, adding and adding and not being particularly careful about how everything has its own space within a production. I’ve been spending more time carving out space, whether that’s with EQ, or reverb, or the stereo image. Lots of drawn-in automation.”

How did you approach vocal recording on this project?

“Psychologically, I try to think of every take as the final one - solo or collaborative. I’ve never really understood what demo’ing is, the idea of doing the final thing later. On a technical front, I record with a dry, compressed sound. I tend to sing a bit more boldly and not hold back if there’s a little ceiling on what I’m doing. I guess it’s also more about microphone technique and understanding the mics better.”

Do you have a preferred mic for vocals?

“It always comes back to a very typical choice, the SM7. I’ve been using a ribbon mic a little bit as well to sing into. But for doubling voices, the SM7 seems to give a much nicer doubling effect than a condenser. It’s nicer as a handheld thing, too, I’ve never been one to stand up.

“I find that whenever I’ve used a laptop mic to do takes, hunched over a laptop, I get way more pleasing results. I try to keep that in mind, recording myself or anyone else, that it’s not always the best-looking or the most professional-looking set-up that gives you a good result.”

You’re both a songwriter and a producer. Do you find that those two disciplines are separate for you, or is it one singular process?

“It’s more separate, recently, because of what I was saying about having people like Jay come in and take something that I’ve started and turn it into a more traditional process. Previously, it’s been all in one, songwriting, recording, production, mixing… it’s a gradual process altogether.

“I do find that quite appealing - having the ability to produce means you can quite radically change songs quite easily with production and sampling. You can turn a mediocre idea into something exciting quite fast. I’m definitely not trying to go towards traditional songwriting too far. It’s great to have both.”

I suppose it’s a different headspace as well, when someone’s come in to jam or write, as opposed to sitting in front of the computer alone…

“Completely. Seeing the shapes of things on the guitar or piano that were previously just blocks on the screen. MIDI chords turn into a physical shape, it’s more interesting and fun to see those appear as you record.

Someone will ask, what if you change the threshold and release on the compressor? It’s like, I guess we could, I don’t know!

“I want to create an atmosphere that’s friendly and funny as well. It gets heavy if things are all a bit professional and serious. It’s good to have humility about not knowing how to use things that you have in the studio. Someone will ask, what if you change the threshold and release on the compressor? It’s like, I guess we could, I don’t know!

“When you’ve got those things, people assume that you know exactly what you’re doing, but I’m still pretty ignorant on a lot of those techniques. I studied music tech and we had a great mixture of ‘here’s how you should and shouldn’t use compression - both work.’”

Are there any albums or tracks that particularly inspired you for this project?

“I haven’t been listening to as much music while making this record. I remember listening to Prefab Sprout’s cover of He’ll Have To Go quite a bit when I started on the album.

“The chord changes, the sonics of it, the drums… how warm and together everything feels, but still quite open, it feels quite natural. The more natural sound is something I was going for with the album; the illusion of less production. I’m really intrigued about how much of an illusion that is with other people’s work, as well. How much time was put into the details, and how much of it was just incidental, because of good engineers and experienced choices. For me, it’s an illusion - it’s just hard work.”

Bullion's Affection is out now on Ghostly International.

I'm MusicRadar's Tech Editor, working across everything from product news and gear-focused features to artist interviews and tech tutorials. I love electronic music and I'm perpetually fascinated by the tools we use to make it. When I'm not behind my laptop keyboard, you'll probably find me behind a MIDI keyboard, carefully crafting the beginnings of another project that I'll ultimately abandon to the creative graveyard that is my overstuffed hard drive.

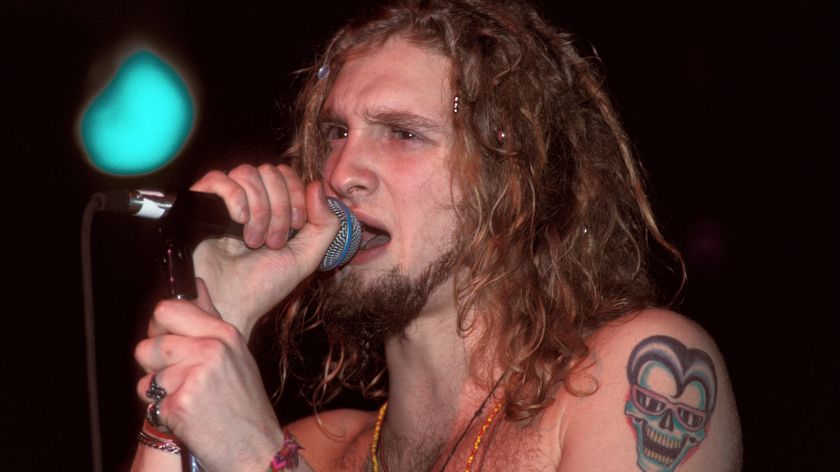

“Radio stations all said Layne’s voice is wrong”: Alice In Chains and Jane’s Addiction producer Dave Jerden helped to define the sound of alternative rock

“U wanna hear the raw files”: Producer Mike Dean tells streamers to switch off auto levelling on every music platform, and hear the music as it was meant to be heard

Most Popular