New ways of hearing: a brief history of ambient music

From ’50s classical experiments to an antidote to ’90s raves, ambient music has proved to be less of a singular genre, more of a creative ethos

What exactly is ambient music? That’s not such a simple question to answer. While the genre of ‘ambient’ is fairly well established, the exact rules of what makes something ambient aren’t rigidly defined.

The basic, sometimes derogatory definition is that ambient is background music. That’s certainly true of some ambient music. Many of Brian Eno’s early works, for example, were specifically created to blend in with the listener’s environment, more like a background texture than an up-front performance. Ambient music can be equally intense and all encompassing, though – providing a sort of sensory overload that locks the listener into its world rather than drifting along in the background.

You could say it’s generally beatless – especially in an electronic context – but this definition excludes rhythmic ambient tracks from the likes of Aphex Twin, and the seemingly contradictory realm of ambient techno.

It’s tough to define by any one specific set of creative tools too, as the genre can take the form of everything from classical compositions to sample collages or self-creating modular synthesis. The most accurate description probably comes down to the general approach; one that places texture and atmosphere above traditional musical structures.

Looking backwards

Though the term wasn’t coined until the early ’70s, the creative approach and musical philosophy behind ambient music had been percolating in the creative minds of various composers and artists throughout the 20th century. The first inkling appeared as early as the 1920s in the works of impressionist composer Erik Satie, who applied the term “musique d’ameublement”, or furniture music, to a number of simple, unstructured and repetitive pieces intended to be performed as background music while relaxing or dining, not listened to directly.

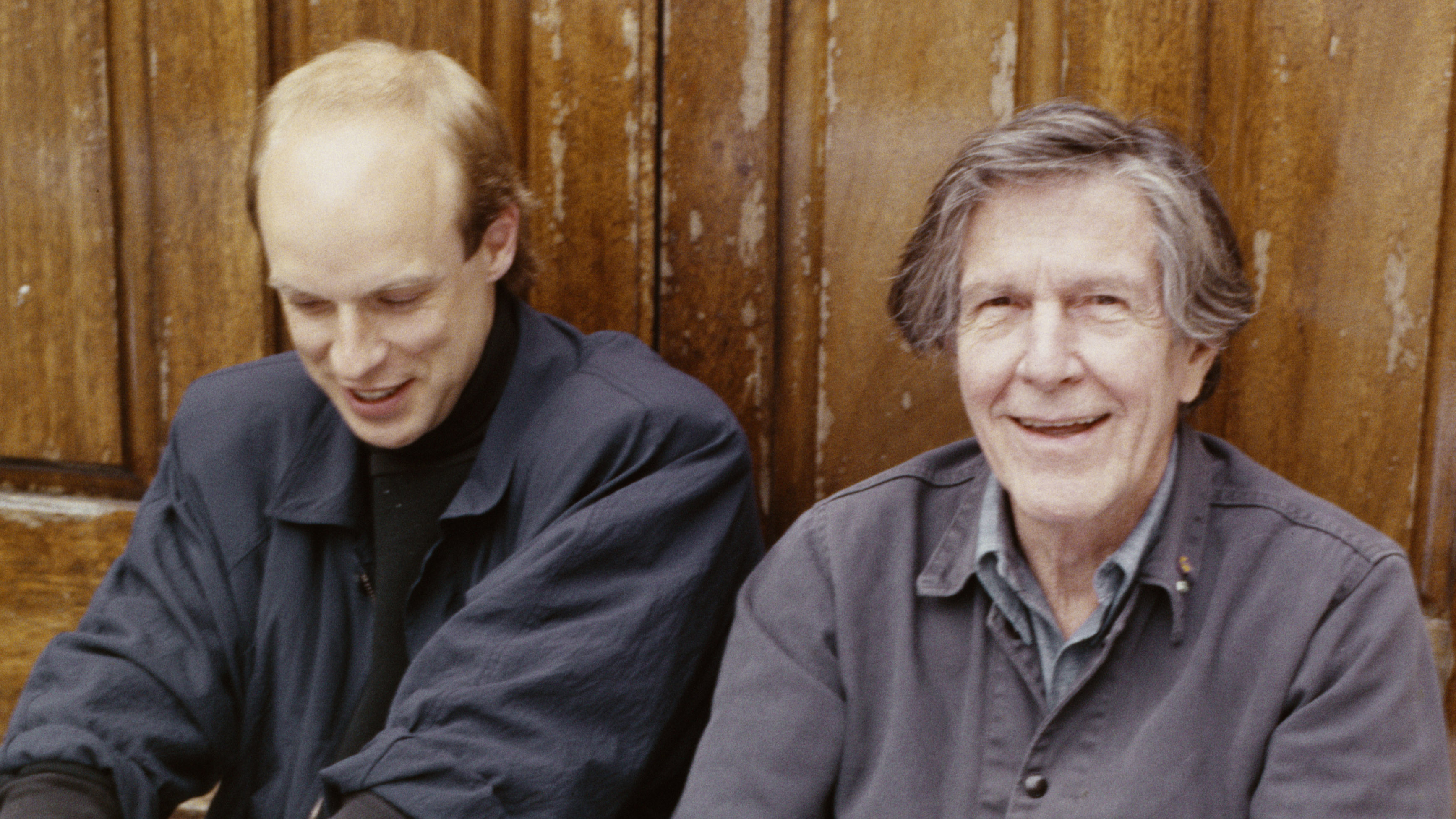

Though not widely performed during Satie’s lifetime, these pieces would go on to be championed by another proto-ambient pioneer, John Cage. Cage, of course, is responsible for 4’33”, the 1952 musical work that consisted of 4 minutes and 33 seconds of silence. By asking the performer to be silent, Cage was asking the audience to redirect their attention to the naturally occurring sounds around them, taking Satie’s idea one step further and clearing a path for ambient music’s emphasis on space and atmosphere.

While Cage was laying essential groundwork for the development of ambient music in the US, composer and musicologist Pierre Schaeffer was spearheading the avant-garde practice of musique concrète over in France. Rooted in what were essentially the first experiments with sampling, musique concrète treated recorded sounds as a compositional resource to be manipulated and processed.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Like Cage, Schaeffer radically reoriented our expectations of what music could be, opening the doors for ambient musicians working decades later to integrate field recordings and environmental sounds into their work, abandoning structure and rhythm in favour of tone, mood and texture.

Baffling the critics

A decade later in the ’60s, minimalism began to take shape, as composers like Steve Reich, La Monte Young and Terry Riley experimented with deceptively simple, highly repetitive arrangements built from long, extended chords, steady rhythms and layered textures.

Baffling many critics of the era, minimalism was incredibly influential: not only did its hypnotic repetition go on to inspire techno and house in the ’80s, it also paved the way for ambient musicians to renounce convention and produce lengthy works that lacked structure, direction, and the kind of harmonic resolution listeners previously expected.

It wasn’t until the late 1970s that the term “ambient music” appeared. Brian Eno coined the phrase, and is regularly credited with inventing the genre, though he couldn’t have done so without building on the advancements of hundreds of pioneering artists similar to the ones mentioned above.

The story goes that a friend of Eno’s brought him an album of 18th-century harp music to listen to while he was bedridden after a car accident. As she was leaving, she put the record on for him to listen to, but left the volume almost too low for him to hear. Unable to get out of bed and turn it up, Eno was left to focus on the barely audible music, which was just loud enough to hear above the rain outside. He’s claimed that this experience taught him a “new way of hearing music, as part of the ambience of the environment.”

Though Eno’s first ambient release came with 1975’s Discreet Music, it was the series of four albums named after the genre that he released throughout the late ’70s that helped to popularise and solidify the term as a genre and a style.

It was in the liner notes for the first of these that Eno most explicitly defined ambient music, claiming that the genre should enhance the “acoustic and atmospheric idiosyncrasies” of the listener’s environment, inducing “calm and a space to think, [...] accommodating many levels of listening attention without enforcing one in particular”, and, most famously, that it should be “as ignorable as it is interesting.” And thus, ambient music was born.

Tools of the trade

Eno’s bright idea came at an opportune moment. Music tech was beginning to develop exponentially, and in the ’80s the first mass-produced synths were released and MIDI was introduced. The audio effects that characterise so much ambient music – reverb and delay – became more widely available through the development of digital pedals and affordable effects units.

As music technology became accessible to all those with a computer in the ’90s, the experimentation continued. Offshoots and subgenres swiftly began to spring up – drone, chillout, downtempo, new age – while producers inspired by the ambient approach (Aphex Twin, anyone?) would go on to merge the style with new sounds to create variants like ambient techno and ambient house.

As the genre developed throughout the '00s and '10s, a more diverse cast of artists began to be represented, with female acts like Grouper, Julianna Barwick and Sarah Davachi, and Black artists such as KMRU thankfully becoming a more visible presence. Today, ambient music is more popular than ever before, and the approach and aesthetic that defines it continues to influence and inspire new generations of musicians and producers working across every genre.

5 key albums in ambient history

1. Brian Eno - Ambient 1: Music For Airports (1978)

The first in Brian Eno’s Ambient series, this was the first album ever to be categorised under the term. Across four drifting and unstructured pieces, Eno comforts nervous flyers by manipulating tape loops of piano, synth and vocals to soporific effect.

2. Midori Takada - Through The Looking Glass (1983)

Influenced by African drumming, gamelan and minimalist composers across the Atlantic, Japanese composer Midori Takada used a diverse range of live percussion and acoustic instrumentation to create a mesmerising masterpiece that was lightyears ahead of its time.

3. Aphex Twin - Selected Ambient Works Vol. II (1994)

On this album’s predecessor, SAW 85-92, Richard D. James perfected ambient techno. The second time around, he ditched the beats altogether and produced some of the strangest and most powerful ambient music that’s ever been recorded.

4. William Basinksi - The Disintegration Loops (2002)

On the morning of September 11, 2001, William Basinski finished working on an ambient project based around the sounds of decaying tape loops. After witnessing the attack from his NYC rooftop that day, he dedicated this harrowing and majestic work to the victims of the tragedy.

5. Julianna Barwick - The Magic Place (2011)

Julianna Barwick used nothing but her voice and a smattering of synths to produce her sublime debut album. Looping, layering and processing and her heavenly vocals, she elicits a bewitching sense of wide-eyed wonder.

I'm MusicRadar's Tech Editor, working across everything from product news and gear-focused features to artist interviews and tech tutorials. I love electronic music and I'm perpetually fascinated by the tools we use to make it.