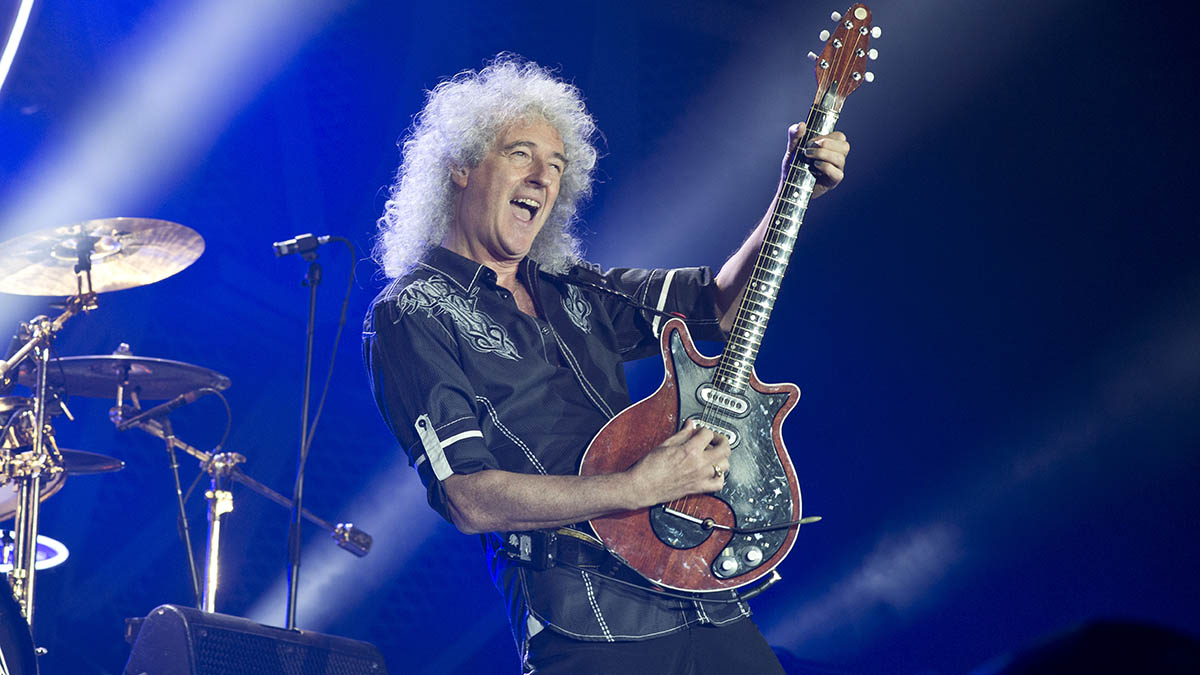

Brian May explains how Queen rewrote the guitar recording rulebook when tracking their self-titled debut – but they were not happy with the album's sound

The sessions found an ascendant band learning to make their own rules but May admits too many overdubs and a "dead" studio detracted from his eureka moment for recording guitar harmonies

Brian May has been reflecting on the recording of Queen’s 1973 self-titled debut album and revealed how it established them as a band who would happily break the rules, even if they were never totally happy with the final sound of the record.

This, after all, was the guitar player with the homemade electric guitar, the Red Special, who would incorporate a homemade guitar amp into his rig, the Deacy Amp – a Supersonic PR80 portable radio that bassist John Deacon recovered from the trash to adapt into a key component of May’s more outré orchestral sounds.

If ever there was going to be a band to stand recording orthodoxy on its head, it was Queen. The sessions for Queen's debut, with demos tracked at De Lane Lea before they decamped to Trident Studios, in London’s Soho, would present them with the opportunity to do just that, as May challenged the received wisdom of the time that said electric and acoustic guitars couldn’t sit together in the mix.

In a recent interview with Total Guitar, May recalls the scene as they prepared to record The Night Comes Down.

- Brian May on 9 Queen guitars that aren't his Red Special (plus his Vox AC-30)

- Brian May's tribute to Jeff Beck

“People in those days used to say, ‘You can’t mix electric guitar with acoustic guitar.’ Nowadays that sounds pretty funny, but it was a belief that people around studios had,” said May. “They would say the electric guitar is too loud for the acoustic and I went, ‘Come on!’ It’s just a question of balancing in the mix. So with The Night Comes Down, it’s based on acoustic guitar, my beautiful old acoustic. But the guitar harmonies are all electric. And that was a beginning, sort of like a demonstration: ‘Yes we can do this, we can make our own rules!’”

They would say the electric guitar is too loud for the acoustic and I went, ‘Come on!’ It’s just a question of balancing in the mix

Finding the alchemic blend of guitar sounds became a leitmotif of Queen’s sound. May’s tone was multi-dimensional. It was a revelation. Harmonised guitars would be all over classic recordings such as The Millionaire Waltz, Good Old Fashioned Lover Boy and Brighton Rock. They spoke to the orchestral impulse in May. They would lend his sound the grandeur of a Royal wedding.

But in the same interview, May cautioned against the use of multi-tracking as a default tactic. Sometimes the more you add, the less you get, and guitar solos can be especially vulnerable to being over-engineered. When tracking their debut, multi-tracking was a bone of contention.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“That was a bit of a fight as well, because people had discovered multi-tracking and there was this feeling that everything ought to be multi-tracked.

“So you play a solo, and the first thing people say is, ‘Oh, do you want to double-track that?’ And maybe you do. But maybe you don’t – because sometimes you want to hear the personality, the attack, and the feeling in the moment when you do that one track.

There [were] an awful lot of overdubs on that first album, which I would say now [were] unnecessary, and perhaps made it a bit more stiff than it otherwise would have been

“So there [were] an awful lot of overdubs on that first album, which I would say now [were] unnecessary, and perhaps made it a bit more stiff than it otherwise would have been.”

Looking back on it now, May says the band were not happy with the sound. Triton Studios was the scene of many classic recordings; Elton John’s Your Song, David Bowie’s The Rise And Fall of Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars, Lou Reed’s Transformer. But May and Queen did not rate it.

“We were thrown into the studio and into a system which regarded itself as state of the art,” he says. “Trident Studios were very emergent as a force in the world. And they thought they had it down. But the Trident sound was very dead. It was the opposite of what we were aiming for. So Roger’s drums would be in a little cubicle, and all the drums would have tape on them. They’d all be dead and down.

“I remember saying to Roy Thomas Baker, ‘This isn’t really the sound we want, Roy.’ And he said, ‘Don’t worry, we can fix it all in the mix.’ Which of course is not the best way, is it? And I think we all knew: it ain’t going to happen!”

I remember saying to Roy Thomas Baker, ‘This isn’t really the sound we want, Roy.’ And he said, ‘Don’t worry, we can fix it all in the mix.’ Which of course is not the best way, is it?

Brian May

That drum sound would explain why Queen reportedly used the demo version of The Night Comes Down on the final release. But even if the band were not happy with the sound, May says they were ultimately happy with the songs. The direction of travel was clear. “We were evolving,” he said. “You can hear in the first album that we were finding our style.”

Of course, the next year they were back at Trident for Queen II, and would go on to record Sheer Heart Attack and A Night At The Opera there – the latter reported to be the most expensive album ever recorded. Surely it can't have sounded that bad, Brian?

You can read the full interview in Total Guitar, which is available now from Magazines Direct.

Jonathan Horsley has been writing about guitars and guitar culture since 2005, playing them since 1990, and regularly contributes to MusicRadar, Total Guitar and Guitar World. He uses Jazz III nylon picks, 10s during the week, 9s at the weekend, and shamefully still struggles with rhythm figure one of Van Halen’s Panama.