Brian Eno collaborators on his new album: “He’s great at making fabulous sounds using Logic soft synths and some third-party plugins… the days of him using modular synths are long gone”

Dolby Atmos mix engineer Emre Ramazanoglu and post-producer Leo Abrahams discuss their roles in the making of the FOREVERANDEVERNOMORE LP

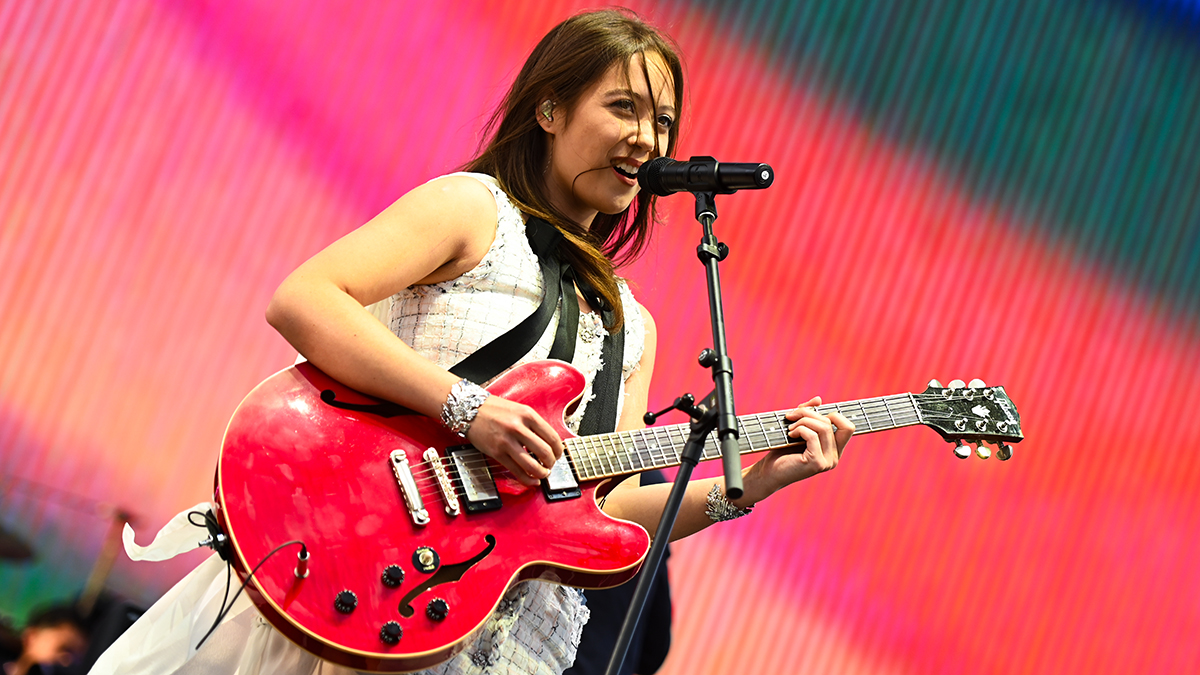

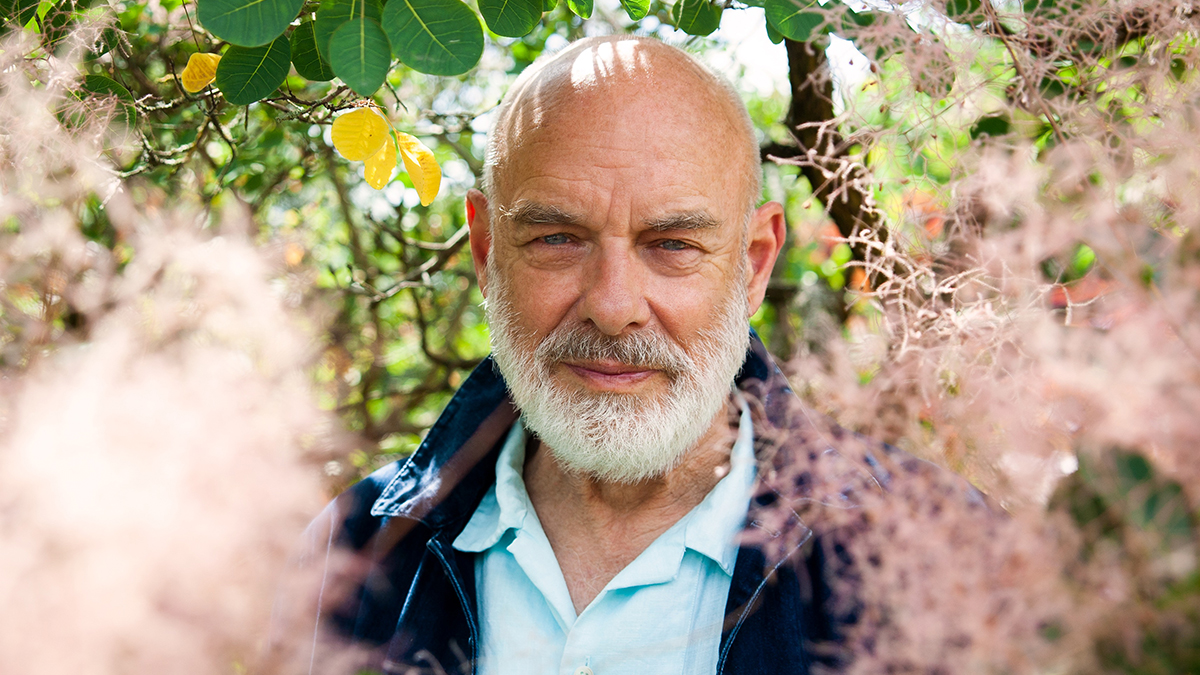

Ambient innovator Brian Eno returns today with his 22nd solo studio album, FOREVERANDEVERNOMORE. The 10-track LP was recorded at his West London studio with vocal contributions from Darla and Cecily Eno and two compositions reworked from live performances at the Acropolis in 2021 with Roger Eno and long-time collaborator Leo Abrahams.

FOREVERANDEVERNOMORE sees Eno sing vocals on the majority of tracks for the first time since 2005’s acclaimed Another Day on Earth. Having spent decades working with spatial audio within multi-speaker environments, Eno invited sound engineer Emre Ramazanoglu to help create a Dolby Atmos mix of the album.

Giving us special insight into the making of the record, we speak to Ramazanoglu about the Atmos mix and how he sees the technology developing, and long-term collaborator Leo Abrahams, who worked closely with Eno on editing and post-production.

Emre Ramazanoglu, Dolby Atmos mix engineer

At what point did Brian contact you to work alongside him on the Blue-ray Dolby Atmos version of FOREVERANDEVERNOMORE?

“That came through Universal Records, who I already do a ton of Atmos mixes for. I’d just done the Jon Hopkins album and have worked quite a bit with Leo Abrahams who played a big part on this record, too. He recommended me because this was more of a specialist project.”

Having got the call from Universal, what was your immediate reaction?

“‘Yes! Yes, please [laughs]!’ It was absolutely brilliant and I couldn’t wait to get started, especially as I hadn’t worked with Brian before.”

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Did you have discussions with Brian regarding the concept of the album prior to working with him?

“Not at first. He sent me a couple of tracks to try but I didn’t really have any brief at all. Then I got a call one afternoon from Abbey Road, where a lot of the Atmos quality control comes from, saying ‘What are you doing now, and can Brian come over?’ It was then that he explained the concept to me and gave me a super-clear brief of what he wanted, which was fantastic.”

Can you explain that brief?

“The idea behind most Atmos mixes is to recreate the stereo mix absolutely identically. So you take the album master stems and master them in the Atmos environment, matching everything to within less than 0.1dB so you have identical levels everywhere. But Brian wasn’t interested in that, he wanted it to be fully immersive and without any front, even though that’s not really how Atmos works. It comes from cinema tech, so when you’re listening to an Atmos mix on speakers you’re facing forwards and hearing it from the front, side and rear.”

Are many studios set up for Atmos recording these days?

“There’s quite a few now, but I was one of the first independent studios to be set up, and that was done in April of last year. I’d been working on projects with Genelec who suggested I get into it and thankfully I listened to them. I’ve got a 7.1.4 system, with two subs for bass management in a fully kitted Atmos room.”

Once you’d been given Brian’s brief, how did your working relationship evolve?

“He gave me the brief and left me alone, then he came in for a day and we adjusted everything until he was happy with it. The whole process was very enjoyable. In fact, it was my best day in the studio for years because Brian was very clear about what he wanted and everything he suggested made the mix better, but then he’s very comfortable working with immersive audio because he’s been mixing in that field for 20 years.”

What element of the Atmos mix is noticeably different to the stereo mix and is that a subtle thing or intended to be subtle?

“It’s very similar in the way that the record hangs together, but quite different from the stereo mix in terms of how it’s balanced, vocal placement and tonal choices. You have to get a feel for where sounds fit, and that’s very track-specific.

“My regular Atmos mixes are exactly like the stereo mix where you’ll be in the middle of it and it will sound more immersive and impactful, but Brian’s mix is a different experience - the songs actually sound quite different. Certain parts are different, as is the balance of perception because, whereas a sound was once at the front, now it might be top-left and some sounds are muted on the Atmos mix, so it’s a complete reimagining.”

Brian was very clear about what he wanted and everything he suggested made the mix better.

Other than requiring a Blu-ray player, how should the consumer prepare themselves for listening to the album in a home environment?

“Blu-ray’s quite rare for Atmos really. Of the 700-800 mixes I’ve done so far, Brian’s album is the only one I’ve done that’s gone to Blu-ray. You can either stream it on Apple Music using normal headphones or use AirPods Max or AirPods Pros to get Apple Spatial, which isn’t the same as Atmos - it’s an Apple derivation of a re-render of a fold-down of Atmos. They put it in their own spatialiser but it doesn’t really take into account what I’ve done binaurally, unfortunately.”

When listening to Atmos, are headphones preferable to speakers?

|Headphones are probably the least optimal way to listen as some Bluetooth headphones will strip out some of the binaural information, although they do read the binaural metadata that I did the mix with.

“Sitting in front of a 7.1.4 speaker rig would be best and I think Brian would prefer people use speakers over everything else, although 5.1 fold downs can be quite good, so a home cinema setup will get the intention of an Atmos mix across. You can use a variety of playback devices like sound bars, Amazon Echo Studio - which is quite good for Atmos - or New Max. There are lots of single array systems that bounce everything around the room so you can hear Atmos, but there’s a ton more stuff coming for consumers on that front.”

In your view, is Atmos ready to supersede stereo? If not, what would need to happen for it to do so?

“It’s still quite early really, but it’s getting there. Some of the stuff I like most about Atmos is not the immersive development but that the headphone and general speaker playback can be much more spacious while maintaining the same balance. You might not even notice that some mixes are immersive, they just feel very coherent. That’s the best bit for me, rather than just creating gimmicky mixes. You can use much less limiting yet it still feels like you’re using the same amount and you get a massively more dynamic mix that doesn’t feel different from the crushed stereo version.”

‘Gimmick’ might be the key word in terms of public perception. Does Atmos face that struggle?

“The best thing about Atmos is that it’s scalable. 5.1 had no translational scalability, but with Atmos you can scale up from two towers to 128 if you really wanted to. The main problem is not the format but that the quality of mixes being done is not consistently great because it’s actually bloody hard to match a lot of mastering across 100 channels of audio and do it properly.

“Lots of people tell me the Atmos mix is a bit soft or not as hard-sounding, but that’s absolute nonsense. Whether on headphones or speakers, every time someone comes into my room they’ll pick the Atmos mix over stereo because it’s identically matched to the stereo mix but feels more engaging, if done properly. There are a lot of things you have to do to make it work well and that’s going to be the biggest challenge.”

Leo Abrahams, post-producer

How did you first meet Brian and begin your creative association?

“I still can’t quite believe it myself, but I was testing out a guitar in a shop in Notting Hill Gate when he walked in. I’d been listening to his music the night before and thought, ‘that’s Brian Eno, just keep doing what you’re doing [laughs]’. Sure enough, he came over and we got talking, then a couple of months later he invited me over to a session at his studio.”

How has that partnership developed over the years, because you’ve worked with him on several projects now?

“Brian likes to jam, so there’s always tons of stuff in his computer archives and he started giving me some to edit and knock into shape. The first fruits of that were on his record with David Byrne, which grew out of his own songs but he decided to take his vocals off and hand them over to David as instrumentals. They needed someone to do comping, put some drums on, a lot of guitar and finishing off-type stuff.”

Brian likes to jam, so there’s always tons of stuff in his computer archives.

Do you think your background in film composition is also attractive to him?

“When I was studying classical composition at college, film music was something that came out of associations with people like Brian and David Holmes, who I wrote some scores with, and I do think there’s a certain shared aesthetic based on the classical composers that Brian was interested in, like Morton Feldman, John Cage or Cornelius Cardew.

“Although we never really discussed it, that’s where the aesthetic crosses over, but Brian is someone who, in a very gentle way, has a strong gravitational pull. He has this way of effortlessly guiding musicians and sets up conditions to make music that allow you to magically end up in his world.”

How did that process unfold on FOREVERANDEVERNOMORE?

“He had a lot of pieces that were three-quarters finished but I’d already known about some because I played on them with Brian at a concert at the Acropolis in Greece. We ended up using the multitracks for those, but it was already clear what the album was supposed to be and therefore my role was to help him finish it rather than conceive it.

“We did discuss things like the idea of slow, drawn out songs and how far he could stretch the song form, and some of these pieces strike me as being quite classical, but while we discussed that it didn’t affect the outcome much.”

The album does have a climate emergency theme. Was that something you needed to buy into to get your head fully into the project?

“That’s in the words and is something that’s obviously filtering through Brian’s creativity and into the end result.

“One of the things that makes him a great artist is that his music’s mediated through art but not didactic. Although Brian’s very politically active and environmentally aware, the album’s not propaganda but a portrait of where we are at this moment in time.”

How did you work with Brian in practical terms? We’re guessing there was a lot more to it than file exchange?

“My role was quite prosaic in that it’s the stuff that everybody has to do when they’re finishing an album in terms of comping vocals, making sure the voice sits nicely in the track and EQing. I was trying to take some of the load off Brian so he could concentrate on finishing lyrics and keeping his eye on the big picture.

“Sometimes you get to the end of a production and think, ‘why doesn’t this quite sound finished?’ Usually there’s just one thing missing and I’d often fix that by adding guitar, some extra part or perhaps taking something out. Sometimes we’d discuss how tracks fitted on the record or whether they might fit better on another record.”

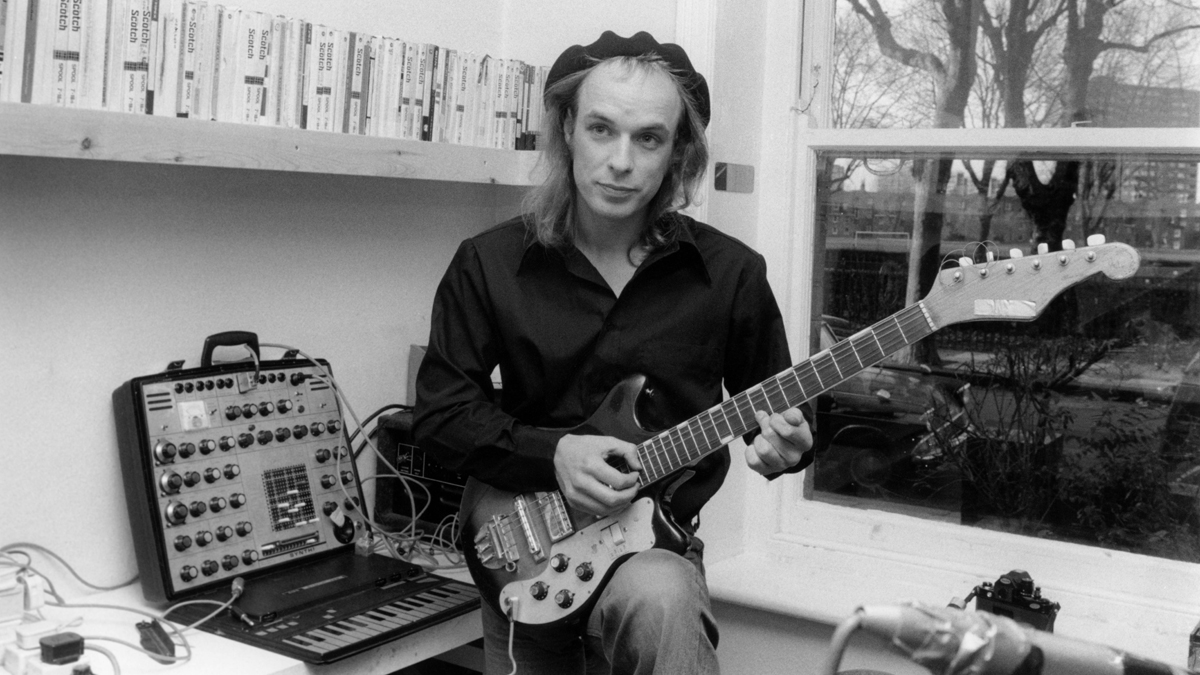

As you worked together at Brian’s studio, you’re well-placed to tell us about some of his gear choices…

“We virtually did the whole album in his studio and if there was ever a fiddly job to do I’d just go into another room with my laptop, bounce everything out to Pro Tools and reimport what I worked on back into his Logic system. Except for the voice, Brian’s pretty much in the box. He’s great at making fabulous synth sounds using Logic soft synths and some third-party plugins and he did play guitar sometimes using a few pedals going into a Focusrite preamp and straight into Logic, but the days of him using modular synths are long gone.”

What did you use for sound design?

“When I do sound design on guitar it’s done through Ableton by building audio racks out of all sorts of different plugins, which I’ll either bounce out or send straight into Brian’s computer, but Brian really does get great results from what’s bundled with Logic. He also uses a lot of sound treatment from Melda and some Native Instruments stuff, but he doesn’t really work with samples that much. He’s more about processing audio and programming Logic’s soft synths for sound creation.”

How do you think this album compares to Brian’s previous works?

“Because his vocal is so prominent, in some ways the album feels like the follow-up to [2005 album] Another Day on Earth, but that album’s song structures were more conventional. FOREVERANDEVERNOMORE feels like something quite new and I see it more as a development of a record he made a few years ago called The Ship, which was a multi-speaker sound installation that featured his voice.”

Brian’s vocal is quite ethereal-sounding on this record. Was it heavily processed?

“Brian’s vocal is one of my favourites because there’s something honest, humane and truthful about his singing. Sometimes his voice is quite processed and other times it’s pretty unadorned, but the lyrics are obviously important so one of the things we played with was how to let his voice have authority without relegating everything else to a backing track.

“That’s really about how much low-end you lend to the voice - he normally records with a handheld SM58 or an AKG mic with a battery, but I brought in an SM7 and he recorded all the vocals on that. It has a slightly more pronounced top and bottom end, which helped his vocal be more prominent without pushing the track back too much.”

Did the principle of him creating a Dolby Atmos mix feed into some of your creative decisions?

“No, because I don’t think Brian was thinking about that while putting the tracks together. Having said that, even before Dolby Atmos was a thing Brian was making multi-speaker installations, so spatial distribution has become a part of his language. There aren’t that many tracks on these songs; often one sound will be made out of several layers and I think that also lends itself to Dolby Atmos quite well.”

What have you learned from Brian that you might apply to your own career, philosophically as much as technically?

“That’s a question I feel a heavy responsibility for answering. I met him in my early 20s at quite an impressionable age and I think he has a very effective balance of seriousness, playfulness and kindness. There have been times over the years when I’ve been producing other artists and realised that I’m trying to do what he does for people, which is to create an environment that’s fun and safe so they can be experimental.

“Above all, it’s just that quality of taking the work seriously and treating it like art rather than commerce, but also being curious and enjoying that curiosity. He’s a very generous and decent person, so I feel really lucky to have met him when I did and still be friends.”

Brian Eno’s latest album, FOREVERANDEVERNOMORE, is out now on UMC. For more information, visit the Brian Eno website.

“Excels at unique modulated timbres, atonal drones and microtonal sequences that reinvent themselves each time you dare to touch the synth”: Soma Laboratories Lyra-4 review

e-instruments’ Slower is the laidback software instrument that could put your music on the fast track to success