Brann Dailor: “I see riffs cinematically”

Brann Dailor reveals his approach to songwriting, why he’s never sung better and what it takes to climb ‘drum mountain’

From Neil Peart and Ringo Starr, to Phil Collins and Roger Taylor, sometimes a drummer comes along who transcends the traditional timekeeping role in a band with an aptitude for lyric and songwriting, singing and more.

Brann Dailor has more than earned his spot on that elite list of drummers with a special set of songwriting, singing and artistic skills that has him leading from the back and elevating Mastodon well above other bands in the prog world.

Everything, from the fantastical concepts that theme each of Mastodon’s albums – from 2004’s Moby Dick-inspired Leviathan to 2017’s tale of death and survival on Emperor Of Sand – to the story-telling lyrics and many of the riffs, is Brann’s work, ably finessed by his musical cohorts Bill Kelliher and Brent Hinds on guitar and Troy Sanders on bass.

Whilst self-deprecating about his songwriting abilities, it’s clear that Brann is Mastodon’s lynchpin, driving the band’s evolution from their ferocious early metal sound, to epic hook-laden prog on Emperor Of Sand, and bagging the band multiple awards and legendary status in the process.

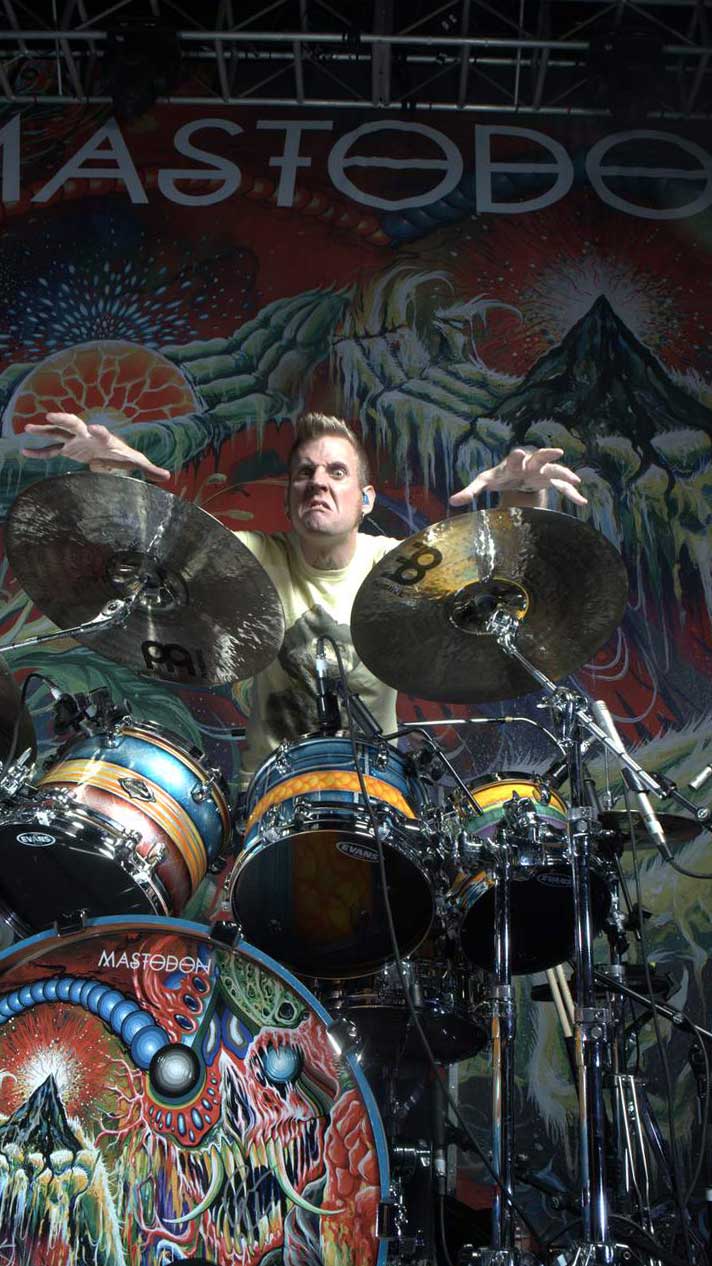

Brann’s drumming is a talking point on its own. A master of rapid fire rolls and shifting time-signatures, the self-taught drummer has developed a deliberately busy style that perfectly matches the unbridled shock and awe of Mastodon’s sound.

That he also contributes vocals whilst drumming at this level is staggering and at times unbelievable, particularly when experiencing it live.

As effortless as Brann makes it look, creating such consistently deep and expansive music requires a deep-rooted creativity and constant graft.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

The drummer reveals that he works relentlessly behind the scenes on lyrics and themes, sweats over making his vocal parts presentable alongside his drumming, and maintains a hardcore practice regimen to keep himself match fit and away from the base of what he calls ‘drum mountain’ – the band’s music may be serious, but as we discover during our interview, Brann’s personality is anything but…

We caught up with him to understand how he approaches songwriting as a drummer, how he has evolved as a player and where his wild ideas come from.

He also lets slip about the possibility of new Mastodon music…

Any new Mastodon music on the horizon?

“We actually just wrote and recorded something. We basically had one foot in the studio and one foot on the airplane to come over here [to the UK].

“We finished it up and we were pretty happy with the mix and the master, so that’s exciting. We were just gonna release it but, oh man there’s always red tape wrapped around everything!

“Scott Kelly sang on this song. The exciting thing for me is that we created something new that sounds awesome and it came out of our studio that we just recently finished building in the basement of the rehearsal facility that we have.

“We bought a building as a band a couple of years ago. Phase one was tricking out about 10 or 12 rooms of the main floor and then there’s a basement so we’ve put 10 rooms down there as well.

“Then we just built a studio. So to give it its christening we’ve put some riffs together, got a song going and we just recorded it to get tones and to see what we got. What does our room sound like for drums? Is it possible to go beyond demoing in our own studio?

“In the past we’ve had some spots where we’ll work on stuff, but we know that’s not going to be a final product type of recording. I can’t put it up against a Crack The Skye and be okay with it.

“Now we’ve got this thing mixed and mastered, I would put it up against anything sonically. The guy that mixed it was like, ‘the raw tones I got were killer’. That’s exciting news that we can potentially not pay those astronomical studio fees and just record at our own spot.

“Also it just opens up a lot of musical opportunities for us. When we’re feeling excited about a riff we wrote upstairs we can take it downstairs and record it immediately. I love that.”

We’re pack rats. We keep all our memorabilia. Each guitar player has 200 guitars or something.

That’s a cool development for the band. Might you start releasing individual songs in the future instead of full albums?

“I don’t know. It’s the sound of dinosaurs dying, but we’re kind of married to the concept of a full album.

“I guess there’s a lot of groups who just release one song and build a tour around it, because the only way anyone can support themselves as a musician these days is to keep your ass out there on stage.

“Which is fine. I like playing live, but it can be physically and emotionally taxing on a person. It’s a lot of work and you’re tired all the time.

“As much as I love that hour and a half on stage, there’s many more hours to fill during the day. Depending on what backstage you’re sitting in it’s either awesome or you sink into some depression a little bit.

“These shows have been killer, so that changes everything usually. You wake up in the morning, you have your coffee, do your thing. Then there’s a dip.

“You’re sitting back there, then it’s time to start warming up, showtime, everyone goes crazy. That moment I guess is what keeps us away from our families.”

The band’s new facility sounds sprawling. Is this something that’s open to other local bands too?

“It’s already filled up. Every room is spoken for by two or three bands. We don’t make any money off it currently but it gives people a place to go.

“I don’t want to call it a crisis or anything, but in Atlanta the two major practice facilities were closed at the same time and knocked down and condos went up. I don’t understand condo living – paying out the ass and you can’t even turn your stereo all the way up.

“There’s lots of homeless bands in Atlanta and lots of bands that weren’t able to start because there’s nowhere to go or practise. If it wasn’t for practice spaces [Mastodon] wouldn’t exist I don’t think.

“We lived in apartments and there was just no place to go. I was hearing about bands practising in storage facilities. People were getting inventive, but they needed a facility.

“Ours by no means fills that void entirely, but it’s a step in the right direction. And we needed a place to practise as well. And a place to call home and keep all our junk.

“We have a ton of stuff. We’re pack rats. We keep all our memorabilia. Each guitar player has 200 guitars or something.”

You must have a lot of kits too?

“Lots of drum kits. They’re actually set up and scattered throughout Atlanta. I got two in my basement, my wife’s kit and my kit set up right across from each other in our drum room.

“Then I have probably three kits stacked up in my room that has videos games and stuff in – I’ve got old 80s Galaga and Ms. Pac-Man games. Bill’s got a little studio over in his basement so I’ve got one of my Randy Rhoads kits over there.

“I got my first Randy Rhoads kit sitting at the practice space. Now in the studio I have a chrome kit. Then I have my tour kit that’s the blacklight sensitive one (see Don’t Fear The Reaper) that’s ready to go in its boxes.

“We have a shipping container that we keep everything in. My stuff is way at the back and it’s completely barricaded. If I wanted to get to it I would have to take everything out of the container to get a cymbal stand.

“I try to make sure I have all my bases covered. I have a small four-piece kit in cases in my basement that’s ready to go, like if I have to play for my wife’s band if their drummer can’t do it or something, I know all the songs.

“Or if I’m playing for one of Brent’s projects then I have this kit that can go into a dirty club. I got kits spread all over. I’m covered when it comes to drums.”

I could be blindfolded and I would know where everything is. I fear change when it comes to drums

You’ve had some crazy kit finishes over the years, but your configuration has barely changed. Is experimenting with kit visuals your way of mixing things up?

“I guess so. For some reason I don’t change; that’s my configuration and it’s comfy. I wrote everything with that configuration so I know where everything’s at. I could be blindfolded and I would know where everything is. I fear change when it comes to drums I guess!

“Tama are an amazing drum company. They’re really good to me and always say, ‘you want another kit?’. I have ideas for themes for kits. I’m always excited to get a new kit because I can do another crazy paint job. I guess I’m more art-minded than I am drum-minded. I look for aesthetic in everything and it makes me happy.”

Do you have a facility to record drums at home??

“Not at the moment. It’s halfway there. I decided to spend some money on my car instead of my recording room. I got a stupid, crazy Cadillac. It’s a 70s Coupe De Ville. It’s a funday Sunday car.

“I take my wife out for a prime rib dinner and a baked potato. It’s a show car. It’s painted like my drums basically and it cost me way too much money. The joke’s on me. Every rocker’s gotta have their cool car, right? I think it’s a prerequisite.”

Mastodon are almost 20 years old and seven albums in. Do you think your drumming has evolved in that time and has anything got easier or harder to play?

“I guess I feel it probably was easier to do the earlier stuff back then. It’s hard to really know. I feel like I play it fine now.

“I’ve learned to maintain a better tempo I think. I’ve settled in, even with the older material. When we played it live I would be so fast. Listening back to recordings I’m like, ‘Jesus Christ, this is so fast!’.

“When we record something, that’s us deciding that’s the speed it needs to be to have the impact we want. Sometimes if you play things too fast it loses something.

“I’ve always wanted to be mindful of it but only in the past five years or so have I really felt like I’ve been mindful of it and been able to execute that mindfulness on stage. When you play live you have this perception that things are too slow when they’re not.”

Is that because of the energy feeding back from the crowd – the excitement of playing live?

“I think it is the excitement. You tend to rush things when you’ve got the adrenaline pumping. There’s a perception in your mind when you’re hearing it and you’re playing along where you think, ‘this is too slow’. You speed it up to where it feels right and comfortable, but listening back it’s way too fast!”

Are you playing to click live to help tame that beast?

“There’s a few songs to click because we do have a few that have keyboard stuff that we wanted to keep [live]. The only way to do that is to play to click and have it kick in when it needs to.

“We don’t do any tracks for vocals or guitars or anything. That’s like crossing the line for us. We want it to be our own bad singing, haha! Which I think has gotten way better actually, and I think that I can safely say it’s the best it’s ever been.”

What do you put that down to?

“Hard work and dedication. Practising all the time and trying to be as healthy as possible on tour. The last bunch of years of actually taking some voice lessons, learning how to properly warm up and warm down after the show.

“Really, honestly approaching it as an important instrument. We’re all reluctant singers in the band. We try to pass the buck on every part, because you don’t want the pressure live. It’s this added thing, especially when you’re drumming…

“We had a singer when we first started, a guy that would scream into the microphone and roll around on the floor. Then two weeks before our first tour he quit. Brent and Troy were like, ‘we’ll just scream s**t into the microphone, it doesn’t matter’. It’s evolved from there quite a bit.

“As far as my drumming style evolving, I think that I’ve changed with the band. If the songs got a little simpler, if the riff structure got simpler, I try to just go with my gut instinct as to what fits the songs the best.

“If something’s complex I try to play along with that. I don’t feel like anything’s really changed.

“I’ve become less busy because the music has become less busy at certain points. I’m the same guy and the same player, I’ve just learned that I want that breathing room as well, for the music’s sake.”

Have you done any work on your drumming since the band formed, taking formal lessons, for instance?

“I’m self taught. I have no idea what I’m doing, but I’ll go down there in my basement and work on stuff. I’ll pick a song I want to learn. Like, ‘I should know how to play the fill from ‘Stairway To Heaven’…’, or this and that.

“This will be in the rare moment in time where we’re in between album writing and tour and when I don’t have to be down there conditioning myself for tour – which I’ll say takes a little longer now – and try to never be at the bottom of what I call drum mountain. I don’t ever want to be there.

“I’ll get home and I’ll stick to my regimen of five days a week and I’ll play for an hour and half to three hours. Sometimes I’ll go all out for two hours solid. Sometimes I’ll have a two-hour setlist and just play the whole thing.

“Or, in the rare instance that I don’t have to do that, I’ll work on independence exercises, or polyrhythms, Afro-Cuban, ‘oh I should learn this Elvin Jones lick’. With YouTube there’s all these incredible players giving free lessons online, so I’ll take in those.”

Songs like ‘Blood And Thunder’ I had the whole thing on a dictaphone from start to finish

So you’ve not felt the need to seek out a teacher?

“I had one lesson when I was a kid, around six or seven. I was a little too young I think and it was boring. He had a practice pad and a music stand and it was right left right left for an hour.

“I already had a drum kit and I was having fun bashing my uncle’s ‘68 Rogers kit. It was dilapidated with two cinder blocks on either side of the kick drum, a snare with no bottom head, hi-hat with no clutch. I learned how to play on that.

“I had a record player behind me, I’d put records on and play along to Deep Purple, Rainbow, Nazareth, some Judas Priest and all that good stuff. I’d be in my own little world up there.

“I’d be up there for hours. I never got into video games or anything, I just wanted to play my drums all the time. When I get home from tour I have a genuine desire to be behind my drum kit.”

So you still get the same kick from playing as you used to?

“Yeah. When I’m not playing the drums I’m thinking about drums, I have beats going through my head. If I leave my drums for too long I get depressed. I have to have them I guess. It’s like a mood stabilising drug.

“Me and my wife have a spot down in Florida. It’s right next to the beach. It’s all good. We’re going to go down there for two weeks.

“That sounds good, but I know in the back of my head that’s going to be too long ’cos I can’t do two weeks without playing drums. I have a practice pad, but that’s a far cry from playing drums.

“I’ll do the two weeks, but that puts me somewhere around base camp. I don’t mind being there, but I don’t want to be at the bottom of drum mountain. I don’t need to be at the top of course.

“Right now I’m at the top of my personal drum mountain, performance-wise, because I’m two weeks into the tour. Two weeks after this I’ll be making weird little mistakes. I think I get overworked and I start to feel fatigued.

“This set is an hour and 40 minutes and there’s almost no talking. It’s almost all drumming. I work too hard y’know. I need to teach myself how to not do that.

“I get up there, it starts and I’m just all in. It completely zaps me. I remember my buddy Dave Elitch saying, ‘honestly, you’re an incredible player, but you work too hard’. I have trouble dialling it back and relaxing.”

Do you still feel physically capable? Are you confident you can maintain your current pace for years to come?

“Yeah for sure. I feel zapped after the show, but I’m alive and well and it makes me feel good, just like I worked out hard. They did a study last summer where they hooked up a calorie counter to my arm to see what was going on during a full set.

“I burned something like 900 calories, like I was on a mad sprint for seven or eight miles. Because of that I can have pizza, a cheeseburger, a couple of beers and be fine!”

Your drumming is a key element of the band and you’re a chief songwriter too. Is there a lot on your shoulders as the backbone of the band?

“I don’t know about that. I’m a helper. I just have ideas and I share them. I don’t prescribe to the thing of, ‘what’s the last thing the drummer said before he got kicked out of the band… I’ve got an idea for a song.’

“Ever since I was a teenager in bands I always had riffs. I’m a musical player I think, I’m a musical person. I have ideas.”

Has that always come naturally to you?

“Yeah, all the time. I offer them up. They don’t have to use any of it. The more the merrier I think and it makes it more of a collaboration with the guys.

“We all welcome each others’ ideas. It literally takes all of us to get an album finished. None of us want to do all the work, that’s no fun.

“I think it’s much more interesting in a band – in the true sense of the word – to have everybody’s ideas in a song, because that makes it ours. I just try to give as many ideas as I can to help the cause.”

What is your approach to writing? Do you start off at the kit, or is it guitar or piano first?

“Guitar usually. I’ll try to ham fist my way through it, because I’m really not a good guitar player. But I’m good at rhythm so I can do that part of it.

“Or I’ll hum it into something like that [points to the dictaphone recording our interview]. My recorder on my phone has probably 300 riffs that I hummed. Sometimes I’ll get one that’s good and I’ll get a second one that marries up with it.

“Or I’ll get something pretty finished. Songs like ‘Blood And Thunder’ I had the whole thing on a dictaphone from start to finish. Songs like ‘The Wolf Is Loose’, ‘Iron Tusk’ or ‘Ancient Kingdom’ I’ll have three riffs, then Bill will sit with it for a little while and have another riff that comes out of that. A couple days later we’ve got ourselves a song. The same thing happened with the song we just wrote. We got this studio set up and I was like, ‘I got two riffs, they go together’. Then I had another one for the ending then we just needed a bridge section. It happens like that sometimes.”

The band has such an established sound and

style. Do you find that your drum parts come easily to you now?

“Pretty much. I like to sit with it for a little while and play around and see if there’s anything more interesting I could do. Then sometimes it ends up being the first thing you came up with was the best idea, the simplest approach. Or there is something more interesting there. It just depends. Sometimes it comes to you immediately, sometimes it takes playing through it a bunch of times. I just try to give it that much time. I don’t want to record stuff immediately and then later be kicking myself like, ‘dammit, I wish I had ruminated on that for a little while longer’.”

I don’t consider myself a writer by any means. I try my hardest for my lyrics to not be embarrassing.

Can you identify a hook as soon as it’s written, or do they take time to reveal themselves?

“Pretty much. You just know. There’s that magic moment. There’s things in the practice space when you start jamming on something and we’re like, ‘yeah, that’s doing that thing that we need it to do where we all lock in and you get the hairs on the back of the neck stand up’. There’s something special there. That’s our divining rod.”

Mastodon’s arrangements can be super complex. How complete are songs by the time you hit the studio, or do you leave room for tweaks?

“Pretty much, but there’s usually a lot of room for vocals. This last record was pretty figured out, but there was a lot of spots y’know.

“You’d sit back and listen and be like, ‘is this a musical section or are we going to sing over it, who’s going to sing?’. We listen through and the part might sound empty to me, or it might sound fine without vocals.

“We tend to vocal everything up, whereas in the past, when there was a lot more screaming involved, there were a lot more musical breaks.

“We listen through to the Remission stuff now and I’m like, ‘wow there’s no vocals in this song until three-quarters of the way through and then they’re sparse. This is weird.’ That’s almost uncomfortable for me now.”

Do you think the vocal element has grown in Mastodon’s music because of your newfound confidence?

“I feel like we search for vocal melody now and our music mirrors the kind of music that we all actually listen to with clean vocals, classic rock and proggy stuff.”

Singing whilst playing drums is a tough job, especially considering the complexity of your drum parts. When writing those vocal parts, you must have to really consider what you’ll be doing on the drums?

“Yeah, I do. When it’s decided that I’ll be strapping on the bit for that section of a song I’ve got to take it easy on the drums. Usually when I’m singing it seems to be a simpler moment in time in the music. I kinda lucked out in that. ‘Aunt Lisa’ [on

Once More ’Round The Sun] is tough. There’s a few where I’m like, ‘I don’t know if I can actually do that,’ and we haven’t played them live yet, probably because of me.”

Once a vocal part is written do you spend a lot of time working on it with the drums?

“Yeah, just to even get it presentable at practice. I’ll just sit down there for hours working on it. There’s been the odd song where I’ve been upfront with the guys and said, ‘that’s not happening, let’s pick another song, or I need more time with that’.”

Leviathan, Blood Mountain and Emperor Of Sand all have distinct themes. What inspires those concepts and does having a theme to write to focus the songwriting process?

“It does for me. I kind of see all the riffs cinematically. I’ll hear a riff and it conjures some kind of cinematic vision in my brain.

“That’s the jumping-off point for whatever the story is going to be usually. For the last record it was the desert.

“I start with an outline like any writer would, then just figure out what the issue is, who the protagonist is, what’s happening in that life and what’s gone down. I start arranging my story ready to share with the other dudes and see if they like it. That’s pretty much my process.

“Then I’ll get up early in the morning, sit in my underwear when it’s really quiet and the cat and dog and everybody’s asleep, I have some coffee and I sit and work on it. You’ve got to put the time in.

“I think it’s a cool extra thing that people can really sink into. I know that I appreciated it with King Diamond. You could picture the story unfolding. We’re not as literal with the stories. You have an overarching theme and then tell the guys they can write whatever they want.

“I don’t want to handcuff anybody to a certain story. Usually they write stuff that makes sense within those constructs. Genesis The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway and King Diamond Them are two of my favourite records because of the stories. It’s not just a bunch of loose songs that don’t really have anything to do with each other.”

Aside from those bands, is there anything else that inspires your writing? Did you read and write fantasy stories at school?

“Not really. Reading yeah, but I don’t consider myself a writer by any means. I try my hardest for my lyrics to not be embarrassing.

“I try to read them out loud to my wife without singing them. That’s how I know if they’re okay or not, or at least passable. If you can read your lyrics to somebody with a straight face…

“If we comb through some of my lyrics I’m sure I’d pull out some lines where I’d be like, ‘I wish that one didn’t make the cut’. After I’m done with my drum tracks it’s like, ‘alright, get to work on those lyrics because they’re not going to write themselves and I don’t think anybody else is going to be inspired to do it’.”

So the lyrics usually get written once you’re in the studio?

“Not always, but a lot of them. I just got to get to work. I kinda hate it, it’s my least favourite part. It’s rewarding when it’s finished, but the process for me is the hardest part about the whole thing: I don’t want to be embarrassed and I don’t have a lot of confidence when it comes to that aspect of it.”

You still feel that way despite the band’s success?

“I’m just self-conscious about it.”

I’m always excited to get a new kit because I can do another crazy paint job. I guess I’m more art-minded than I am drum-minded. I look for aesthetic in everything and it makes me happy

You have a lot of experience recording. In your opinion, what makes a great recorded drum sound?

“I usually have a drum sound in mind, a focal point. Heart’s ‘Barracuda’ is what I said for the last record. I think it’s good to have some idea of what you wanna hear.

“I’d say Genesis Duke, too, for those barking toms. I want it to sound like a modern version of that. Usually the producer and engineer want to do that.

“We also pick guys that are not necessarily metal producers. We pick more rock guys because I like rock-sounding tones. I consider myself in the Bill Ward camp of metal drumming as opposed to the Vinnie Paul side. Both amazing players, but I hear more of myself on that side when metal was first being born.

“For the people who were playing it, metal didn’t exist yet. They knew jazz, but they were trying to compete with Marshall stacks so they have that fusion thing happening. I feel like that’s where my sensibility lies as far as drumming.”

Crack The Skye was the first album you recorded to a click. You expressed a little trepidation at the time, but you got over it quickly. Have you recorded to a click ever since?

“Pretty much. I like it. Old reliable. Sometimes we’ve faded in and out, but for the most part we keep it there. It takes the guesswork out of it. I don’t know if it takes the emotion out. That’s what I was afraid of at first.

“You naturally speed up and slow down due to this and that, the feeling of the song. I feel like the feeling of the song is still well-represented even though it’s locked in with the click.”

Alongside the music, Mastodon are known for cool videos and far-out visuals. Does your record label give you a lot of artistic freedom?

“They’re supportive and they don’t really talk to us. We tell them some whacky idea and they’re like, ‘that’s cool’. They let us do what we want.

“They probably feel like we’re very much in charge of our artistic journey and that it’s one less thing for them to worry about because they probably have bands they need to mould and shape.

“For us we’ve always had a wealth of imaginative ideas for what to do, so they just look forward to whatever we’re gonna come up with. They trust us because it seems to work – this mix of really heavy serious subject matter, then this playful, extremely dry and sarcastic side that somehow works together.”

I'm MusicRadar's eCommerce Editor. In addition to testing the latest music gear, with a particular focus on electronic drums, it's my job to manage the 300+ buyer's guides on MusicRadar and help musicians find the right gear for them at the best prices. I dabble with guitar, but my main instrument is the drums, which I have been playing for 24 years. I've been a part of the music gear industry for 20 years, including 7 years as Editor of the UK's best-selling drum magazine Rhythm, and 5 years as a freelance music writer, during which time I worked with the world's biggest instrument brands including Roland, Boss, Laney and Natal.

"At first the tension was unbelievable. Johnny was really cold, Dee Dee was OK but Joey was a sweetheart": The story of the Ramones' recording of Baby I Love You

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track