Bootsy Collins on James Brown and the state of bass: “He told me one time, ‘Son, y’all the greatest band in the world, but you just can’t play’. Haha! And the bad thing about it was that he was serious!"

Celebrating the day Funk bassist extraordinaire's 70th birthday with a look back at our 2018 interview

If you play any form of funk bass guitar, you owe Bootsy Collins - the legend who’s played with James Brown and Parliament-Funkadelic, like you didn’t know that already - a serious debt. Joel McIver meets the great man for tears of laughter, tears of sadness and enough groove to sink a battleship.

We feature some bonafide bass legends, for sure, but very few come with a pedigree quite like William Collins, or Bootsy as he’s known to the entire bass-playing world (and significant chunks of it beyond).

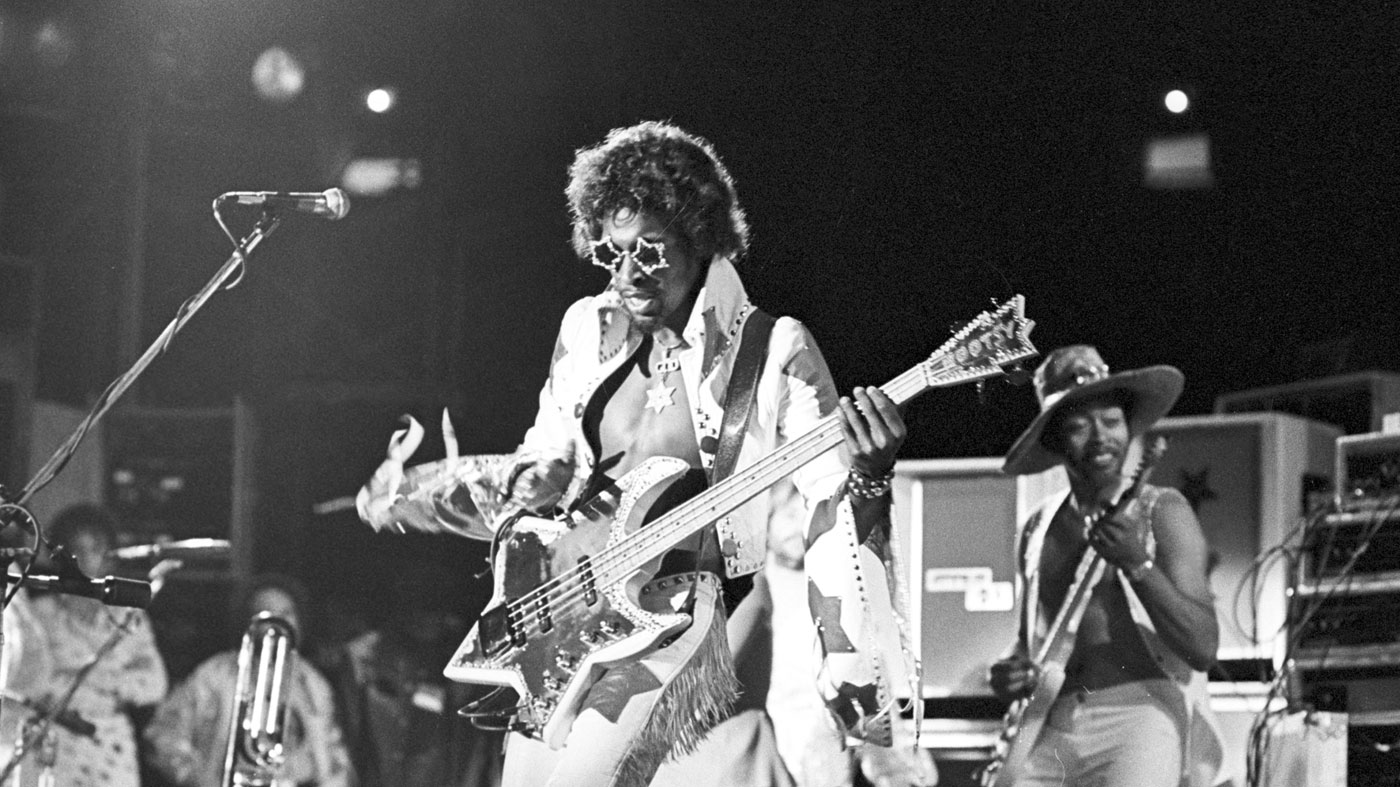

If you’re familiar with the man and his playing, you’ll know what a force of nature he is, epitomising the stagecraft of the era in which he grew up, and laying down the parameters of the slap and the pop for a generation of bassists.

If you ever get a chance to sit down with Bootsy and talk music, make sure you take it: the man is hilarious, unstoppable and also emotionally honest

Check for footage of Bootsy in full flow at any stage of his career, but especially in the 1970s and 80s, when his work with the psychedelic funk bands Parliament, Funkadelic and their many spinoffs lit up the rock landscape, and you’ll be confronted by an explosive figure.

Bootsy was, like his hero Jimi Hendrix and his contemporaries Sly Stone, Larry Graham and Verdine White, a musician who introduced an air of extrovert madness to his performances and recordings. There was, and is, literally no-one like him. When we catch up with Bootsy for a chat about his new album, World Wide Funk, we’re braced for an encounter that is as unhinged as his on-stage character would suggest. But no - the now 65-year-old legend is cool as a cucumber, mellow to the core and simply happy that we like his new tunes.

Mind you, after the career Bootsy's had, he’d need to be a pretty cool thinker just to get through the day: he started out in 1970 with James Brown, a bandleader for whom the phrase ‘mad as a box of frogs’ might well have been coined (see below for evidence). His next big band was the aforementioned P-Funk collective, whose influence has permeated the very DNA of hip-hop and modern soul, while his own Bootsy’s Rubber Band took the brand even further.

Solo albums and collaborations with artists as diverse as Deee-Lite, Talking Heads, Bill Laswell, Herbie Hancock, Buddy Miles and his current guitar partner Buckethead have ensured Bootsy’s legacy. Not to mention his Funk University, an online school where he teaches alongside tutors Les Claypool, Meshell Ndegeocello and Victor Wooten. Can we cover all this in a single interview? Hardly - but if you ever get a chance to sit down with Bootsy and talk music, make sure you take it: the man is hilarious, unstoppable and also emotionally honest.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

State of bass

Your new album is great, Bootsy.

“Oh, man, thank you. That’s so cool to hear. I think the hardest thing about the record was getting it started. You get to the point where you don’t want to do the same things, and wind up with the same cats, so I tried to add some new energy - a little facelift, or ‘funklift’ if you will - just to keep things going. Once we started rolling with it, I realised that it was defi nitely the direction I wanted to go in.”

How did you hook up with your co-producer Alissia Benveniste?

I don’t think anybody owes me anything: we’re all in this universal mixing pot, and you grab certain things out of it and you make it your own

“She sent me a few of her YouTube recordings and I saw that she called her band the Funketeers, so we started talking on Facebook. The next thing you know it’s like, ‘We need to hook up, I want you to do some stuff on the record.’

“I found out she went to Berklee, which was cool because Buckethead and I had gone there to do a bass clinic and talk to the kids and give them a demonstration. We started doing stuff and it turned out great. She’s defi nitely all up in the funk mix. She can pretty much do any of it.”

You’ve also worked with Chris ‘Freekbass’ Sherman in the past.

“Oh yeah - I could see an early version of me in him. We did everything we could do to help get him out there, because I knew once he got out there he was going to be on, you know. It all worked out really good.”

Are you aware that you’ve influenced a huge number of bass players?

“I look at it like everybody brings something to the table, and I have a signature style and sound - and everybody else is either developing that, or getting it together for themselves. I think it’s a good thing. I don’t think anybody owes me anything: we’re all in this universal mixing pot, and you grab certain things out of it and you make it your own. That’s the way I look at it.”

Nowadays funk bass is faster and more technical than ever, it seems, at least judging by the bassists we interview.

“They’re taking it way, way, way beyond, and it’s a good thing, because at one time I remember when a bass player was the scum of the earth, you know? You were the last one to get chosen in the band. Now it’s like ‘You play bass? Oh, cool!’ It’s the thing now.”

When did that happen, from your perspective on it?

It’s all just growing and growing. Nobody knows how far it can go, other than Victor Wooten!

“It was a gradual thing - it didn’t happen all of a sudden. I think I was a part of the change, because Jimi Hendrix was my superhero, and I threw a little bit of his style into the bass. Now they’ve taken all of that and much more. They took what Larry Graham had done and tripled and quadrupled it and funked it up, and it’s all just growing and growing. Nobody knows how far it can go, other than Victor Wooten! It’s a good time for bass.”

You were contemporaries with Jaco Pastorius. Did you know him?

“I never met him. I did know of him, but I never had the chance to meet him. I got hip to him when he was doing his thing with Weather Report.”

Gear of the years

You’re known for star-shaped basses. Is the five-pickup Warwick Space Bass still your main instrument?

“That’s the main puppy right there. They hooked me up, man. I got two of them that I take on the road, and one prototype that they made at fi rst. It’s heavier than the other two, so I keep that one at home. The two I take out have worked out really good: they’re pretty happening.”

What about amps?

“I go into different amps. On the new album I used my original Alembic preamps and Jonas Hellborg preamps, then Mesa/Boogie, Hughes & Kettner and Crown amps, with JBL speakers. I’m also talking right now to Funktion-One, a company in the UK that makes 32” speakers. They do a lot of electronic music and DJs and all that stuff. I’m thinking about having 32s on my low end instead of the 18s.

“We went over there and they showed us a whole system for the mids, the highs, the ultra highs and the sub lows - we’re talking about putting together the whole thing. It’s incredible, man - you walk in and your pants start waving. It shakes everything! I’m really looking forward to getting into that in 2018.”

Do you ever take any of your old gear out on the road?

The Star Bass is hanging on the wall in my meditation room here, safe and sound. The Warwick bass is on patrol now

“I don’t take the original 1975 Star Bass out no more, because in 1998 we flew over to Europe and when we got there, the airline couldn’t find my bass. It took two weeks to get it back! Bernie Worrell knew this one chick that worked at the airline, so he called her up and asked her if she could go down and look for it, because she knew what the bass and the case looked like. She went down and looked for it, and she said that it was just sitting over in a corner by itself.

“Who knows how long it would have stayed there? So after that happened I was like, okay, I got to get a new bass. That one had been stolen before, back in the early days when I first got it made, so I wasn’t having anyone steal it again! It’s hanging on the wall in my meditation room here, safe and sound. The Warwick bass is on patrol now.”

Which other basses do you still have?

“The Funkadelic bass that I played is in the Hall Of Fame, but I still have a ton of my old basses. You remember the 1958 Ampeg with the holes? I got that one, fretless. Victor Wooten came up and broke that in. Oh man, he killed that sucker! We recorded a whole 60 minutes of Victor just playing that bass non-stop. It was incredible.

“It’s still got the same strings that came on it, these old flatwounds. You don’t get that sound now, because everyone wants a brighter, poppier sound. Man, I played that sucker the other day and I was like ‘Wow!’

“And then I got this Vox bass - remember those old hollow-bodied ones? It’s like a Gibson, but with a single cut. It’s got fuzz on it, and sustain, with the little buttons you can push. I played that the other day too. I’m re-finding myself, because those are the basses that I started off with.

“Getting back to that stuff was a great feeling, and it’s a great feeling on this record too, to get back to some bass-lines. That was important to me: we’ve taken it way beyond what a bass player is, which is cool, but I wanted to get back to playing a bassline.”

RIP Bernie Worrell

It was great to see a track dedicated to the late Bernie Worrell on your new album.

“What I had to say, I had to put it on record, because you don’t know what to do with that kind of loss. We did so many things together - so many things - and most of it, people haven’t even heard. There was some kind of connection between us. You know when you use GPS to work out how to get somewhere from over here? We kinda had that with each other from day one, the fi rst time we started playing together.”

He always came across as more introverted than you.

“I was always a pretty good talker: I would be on the street, rapping with the fellows, you know, so I was always pretty good with that. A lot of people would make fun of Bernie under their breath, because he couldn’t do interviews, and stuff like that which seemed easy to do.

“He could play all the keyboards in the world, though, and I always knew that whatever he needed to say, he’d do it on a keyboard. That was why his playing sounded so real, because it was stuff that we were all going through. I could see Bernie trying to explain things to people, and I’d say ‘If only he had his keyboard!’ Haha!”

Do you look back fondly at the early part of your career?

“Coming up at that time was the best, because we had a chance to experience the free love and the peace. Now, getting a chance to share that again is what I love. Those good vibes, man.

“Everything is a choice: you can share the good vibes, or you can get your business hat on and start sharing all of that mess. We weren’t used to business back then: all we wanted to do was play, especially in the era we were coming up in, which was about playing and getting a few girls and having a good time. It all turned into business, though, and since we didn’t know nothing about business, we kinda freaked out, haha! We all went a little crazy...”

The two hours on stage, communing with your fans, never goes away though - right?

I know Bernie’s physically gone, but I still feel him. His setup is still down in the Bootcave

“Yeah. That’s all you have to hold onto, plus the time you have together, even if it ain’t with the whole group. Bernie would come to my house just to get away from everything. All he wanted to do was just walk by himself, and to be allowed his space. I guess every person would want that, but he really needed it, because he was pure genius. He handled it the best that he could, for a good while.

“I couldn’t do enough for him, I wish I could have done more. You don’t get friends and musicians like that, it just doesn’t happen. I don’t take it lightly. When you start talking about him, it’s way under the skin, you know? It’s like he’s in my skin; something you can’t get rid of, and you don’t want to get rid of it. I know he’s physically gone, but I still feel him. His setup is still down in the Bootcave, and for me, he’s still there. He’s still there. If I can do anything for him now, it’s to remind people that Bernie was the key to the mothership.”

Dr Jekyll and Mr Brown

I have to ask this question. What was James Brown like?

“Oh! [bursts out laughing] Oh man... he was that guy, you know. He was definitely that guy! He was a hell of a cat. He worked day in and day out, and you wouldn’t understand why he did the things he did, because he just felt that he was by himself. I never understood that, until I got into having to take care of business of my own.

“When I was with him, he kept me real close, to show me things, as if he knew that I was going to be out there myself one day. He showed me as much as he could, without telling me anything. He had me flying on the jet with him, telling me that he'd called the radio stations and had them play his songs. He’d go there personally, and he’d take me with him to do this. Not only did I play the shows, he wanted me to see him taking care of business, for some unknown reason. He was hard core, man. Hard core.”

Wasn’t he famously stingy with money?

[With James Brown] it got to the point where I had to figure out whether this mother was crazy or if he was just messing with us... It was both

“We didn’t get hit as hard as his first band, because he couldn’t threaten us with taking our money. We were used to getting no money no way, hahaha! Man, I’ve seen some stuff... with James, he would always try to break you down.

“Any time that you knew you’d played a great gig, and the people were loving it, he’d call you into his dressing room and say [adopts sarcastic, guttural tone] ‘Haaargh! You just ain’t on it. You just ain’t on the one.’ I’d be like, ‘What? We ain’t on the one?’ He’d do crazy stuff. He called in the sax player once and told him to throw his horn away because he wasn’t playing nothing but trash. And he was serious. It got to the point where I had to figure out whether this mother was crazy or if he was just messing with us.”

And which was it?

“I determined that he was both of them. He was crazy and he was messing with us! But I gotta say, him telling us that we weren’t on the one and we weren’t happening, it made me want to practise more. He knew what he was doing. You know how sensitive musicians are. That was the biggest letdown, because I was a kid wanting to please Mr Brown and do the best job - and then he called me in the room and told me that. I’m like, ‘Man, what can I do?’

“He told me one time, ‘Son, y’all the greatest band in the world, but you just can’t play’. Haha! And the bad thing about it was that he was serious! Couldn’t nobody laugh about it at the time, because this was Mr. Brown talking, you know. But when we saw how stupid this stuff was that he was doing, we just started cracking up any time he would say something like ‘Errrgh! You’re not on it, son’. We would die laughing.”

What was his reaction to being laughed at?

He was sweating profusely, his knees were bleeding - we just wore him out, and he would still call us in and tell us it wasn’t happening

“Man, it worked because he stopped calling us in the dressing room. We knew we had it, and we said, ‘Okay, that’s what that was all about’. But before that, man, he was killing us with all that ‘Y’all ain’t on it’. He was sweating profusely, his knees were bleeding - we just wore him out, and he would still call us in and tell us it wasn’t happening. And then, when you went out there and messed up, and the show wasn’t really good, we’d all go back to the dressing room with our heads down because we’d had a crappy night.

“Sometimes you just have crappy nights, you know. He would call us in there and he’d be laughing, and he’d say ‘Haaargh! You’re killing it! Son, you’re killing it!’ When he did that, that’s when I really knew that this mother was gone. He was on another planet. Haha!”

Thanks for sharing, Bootsy. You’ve had a career like no other.

“All this happened for real, man, for real. You couldn’t make nothing like that up...”

World Wide Funk is out now on Mascot Records.

“They didn’t like Prince’s bikini underwear”: Prince’s support sets for the The Rolling Stones in 1981 are remembered as disastrous, but guitarist Dez Dickerson says that the the crowd reaction wasn’t as bad as people think

“We are so unencumbered and unbothered by these externally imposed rules or other people’s ideas for what music should be”: Blood Incantation on the making of Absolute Elsewhere and how “Data from Star Trek” saved the album – and the studio